Art World

Need an Absorbing Read for the Holidays? Check Out These 13 Books Recommended by the Artnet News Staff

Let these artsy books transport you to another place this holiday season.

Let these artsy books transport you to another place this holiday season.

Artnet News

Many of us didn’t get to see a lot of art this past year, and it’s looking like we’ll be holed up for a few more months this winter. So why not do the next best thing and immerse yourself in an artistic world through reading?

Our editors and writers hand-picked some of our favorite books to transport yourself to another place this holiday season.

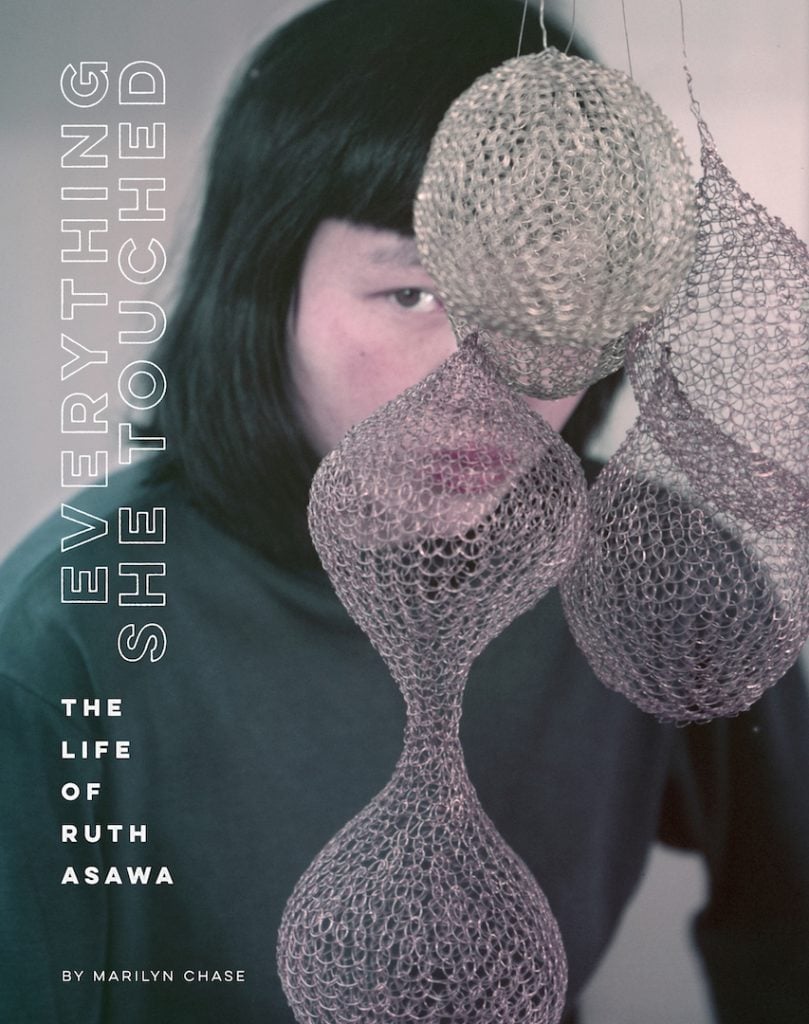

Everything She Touched: The Life of Ruth Asawa by Marilyn Chase (2020). Courtesy of Chronicle Books.

The life and career of Ruth Asawa was nothing short of amazing, as this biography shows. A Japanese American forced to relocate to an internment camp in Arkansas during World War II, she overcame the odds to become an acclaimed artist. Moreover, Asawa channelled that experience into her work, developing a unique style of woven sculptures, her use of wire inspired by the internment camp fences designed to unjustly imprison her people. A graduate of famed Black Mountain College in North Carolina who was mentored by Josef Albers, Asawa maintained a thriving practice even as a mother of six in an interracial marriage. Author Marilyn Chase spent five years researching her life story, drawing in fascinating details on the artist’s letters, diaries, and sketches, and interviewing Asawa’s loved ones. The book also includes 60 images of Asawa and her work, including portraits taken by her close friend and acclaimed photographer Imogen Cunningham.

—Sarah Cascone

Moyra Davey’s Index Cards (2020). Courtesy of New Directions Publishing.

Discursive and diaristic, Moyra Davey’s essays are a lot like her films. Begin one of the 15 texts in Index Cards, collected together for the first time, and it’s impossible to know where you’ll end up. An essay on “Photography & Accident,” for instance, makes its way through ruminations on Virginia Woolf, Kerry James Marshall, and Freudian psychoanalysis before reaching its terminus 30 pages later. But like any good trip, the journey is the destination, and Davey’s text, which slips effortlessly between styles (memoir and prose poetry, critical reading and autofiction) and textual references (literature and art history, film and philosophy), is just a joy to read.

—Taylor Dafoe

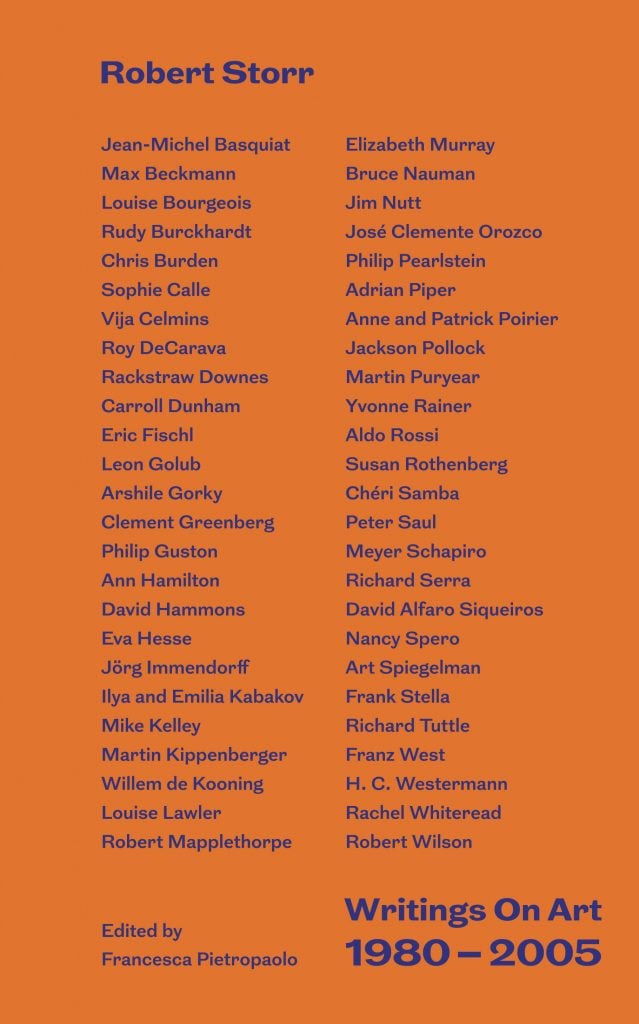

If anyone is still unconvinced about Robert Storr’s critical acumen, this exceptional volume should dispel all doubt. The book, edited by Francesca Pietropaolo, collects many of Storr’s best writings, including a revelatory essay on the influence of Mexican muralism on Jackson Pollock, and an erudite and damning, if slightly overheated, polemic against Clement Greenberg.

In her introduction, Pietropaolo notes Storr’s ability to work in a variety of registers. He can write in long-form without overstaying his welcome; draft short items that are compact but not dense; and has an uncanny intuition for rarely seen connections between artists as seemingly far-flung as Louise Bourgeois and Adrian Piper. The book—the first of a planned two-volume set devoted to his essays—is a follow-up to Storr’s collected interviews with artists, also edited by Pietropaolo.

—Pac Pobric

By turns rapturous, claustrophobic, and heartbreaking, Samanta Schweblin’s acclaimed novel gravitates around questions pivotal to contemporary art in 2020: Can remote experiences ever plausibly replace the real thing? Where do you draw the line between observer and participant? How can objects impact our understanding of each other and ourselves?

Schweblin investigates these themes by weaving a small group of first-person narratives through imagined devices called kentukis. Although they look like animatronic stuffed animals and can make only one noise, the real intrigue of the kentukis lies in their usage. Each one facilitates a relationship between an anonymous “dweller”—a single human user who controls the kentuki via internet connection—and a “keeper”—a single human owner who hosts the kentuki as a kind of 21st-century pet, with no guarantees about the identity or intentions of whoever will inhabit it. Even without the drama Little Eyes unfurls at a Mexican artists’ residency, it just may be the perfect novel for new-media freaks and tech junkies in this dystopian year.

—Tim Schneider

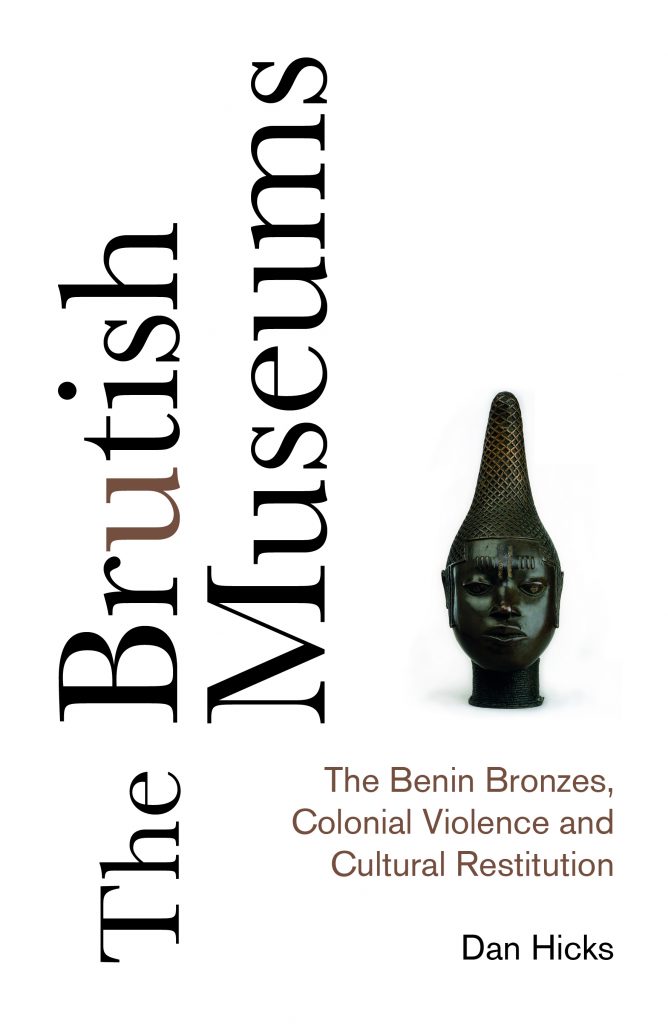

The Brutish Museums by Dan Hicks.

The Pitt Rivers Museum curator and Oxford professor of contemporary archeology Dan Hicks hones in on the history of the violent plundering of the City of Benin by British troops in 1897 during the course of a so-called “punitive” mission to justify an imperial advance on Nigeria.

More than 10,000 artworks and sacred ritual objects, including the Benin Bronzes, were looted and put on public display as part of a concerted propaganda strategy of Western superiority over African civilizations. Hicks argues that institutions that continue to hoard and display these monuments to white supremacy—and he counts among them at least 150 “brutish” museums and galleries around the world from the Met to the British Museum—are complicit with its enduring effects on society.

The book offers a detailed history of the artistic development of these objects, and how they have variously been mythologized, spin-doctored, and sanitized by the institutions holding onto them. Hicks agitates for museums to dismantle the legacy of white supremacist ideology within their galleries—particularly in Britain, where Victorian colonial history still looms large—through definitive acts of cultural restitution and reparation, and in making those histories visible in all their grisly colors.

—Naomi Rea

Nicole Fleetwood had a lot of doors closed in her face over the years when she wanted to do an exhibition about art made in prisons. But as attention has turned more and more to the brutality and injustice of the United States’s system of mass incarceration, she finally was able to organize a moving exhibition at MoMA PS1 in New York (through April 24, 2021), including work by currently and formerly incarcerated artists like Dean Gillispie, Mark Loughney, and Jessie Krimes, as well as contemporary artists who address the theme from outside prison’s walls, like American Artist and Sable Elyse Smith.

This remarkable book is the result of Fleetwood’s years-long journey, starting from experiencing the pain and shame resulting when family members and others from her communities disappeared into jail and prison for years, decades, or life. In powerful prose that’s as humble and clear as water, she makes visible the creations of those our pathologically punitive society has done its best to make invisible.

—Brian Boucher

Emily Segal’s Mercury Retrograde (2020). Courtesy of Deluge Books.

For her debut novel, the incisive artist and thinker Emily Segal travels back to post-Occupy Wall Street New York—her hometown—where a Trump presidency is a distant but looming possibility. Segal, a founding member of the artist collective K-HOLE and co-founder of the think-tank Nemesis, explores through this autofiction that peculiar but decisive blip of existence in the 2010s, through the eyes of an artist and forecaster navigating through the start-up world.

–Kate Brown

Legacy’s Russell Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto (2020). Courtesy Verso.

The US curator and writer’s recently published book explores urgent questions around the body, gender, and identity and their relationships with technology. The book is in part a memoir and a powerful cultural theory that builds upon the term “glitch feminism,” which Russell first coined in 2012. The book also provides a review of contemporary artists who have incorporated the glitch—a blip or an error in the digital stream. As Russell so aptly said in a recent interview with Artnet News, Glitch Feminism is “a demand to center certain questions tied to what artistry is and who is and is not made visible, looking at art as it exists through, and is inspired by, the internet and digital culture.”

– Kate Brown

The 99% Invisible City: A Field Guide to the Hidden World of Everyday Design by Roman Mars and Kurt Kohlstedt. Courtesy of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Roman Mars and Kurt Kohlstedt have turned their architecture and design podcast 99% Invisible, about the seemingly insignificant things that keep our cities running, into a book. Functioning as urban detectives, they solve mysteries hidden in front of your face, like why traffic lights have red on the top and green on the bottom—and celebrate the functional design elements that are woven into the very fabric of urban life.

—Sarah Cascone

Image courtesy of Pegasus Books.

The latest art thriller from the director of security and chief investigator at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Anthony Amore, delves into the intriguing life of Rose Dugdale, one of the rare examples in history of a woman pulling off a major art heist. Born into a wealthy family in the UK, Dugdale walked away from her life as an Oxford-trained PhD and heiress to take up the cause of the Irish Republican Army.

In 1974, Dugdale was the mastermind behind one of the biggest art thefts in history, leading a gang into the lavish Russborough House in County Wicklow and making off with millions of dollars in art, including works by Francisco Goya, Thomas Gainsborough, Peter Paul Rubens, and Johannes Vermeer. Amore deftly tells the intriguing story of her idyllic upbringing in Devonshire and presentation to Elizabeth II as a debutante, to her unbelievable turn to a life of activism and crime.

—Eileen Kinsella

Image via Duke University Press.

The art market makes a lot of headlines—in this publication and elsewhere—but much less often does it get the thoughtful scrutiny it deserves. And that’s because such scrutiny takes surgical precision and a complex understanding of the many non-market factors, like racism, nationalism, and classism, that shape the big-money sales we see (and the ones we don’t). Anthropologist Arlene Dávila tackles these thorny issues in her essential book, which explores why Latinx artists have been so poorly served by the art world and international art market—and how that can change.

—Julia Halperin

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing.

After moving to New York in her mid 30s, Olivia Liang struggled with loneliness and its stigma. In this book she explores the theme through the works and lives of various artists such as Andy Warhol, Edward Hopper, and Klaus Nomi. Through their stories she finds that the feeling can be resisted and that, “The idea that loneliness might be taking you towards an otherwise unreachable experience of reality.”

—Sonia Manalili

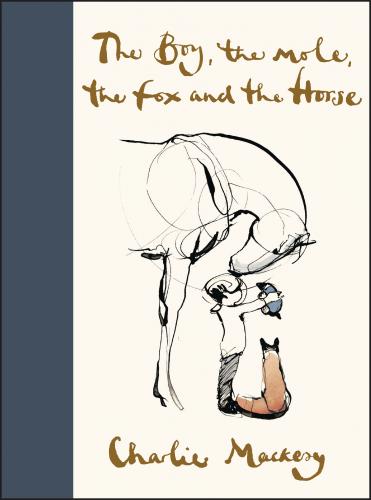

The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse by Charlie Mackesy.

This beautifully illustrated fable tells the tale of a boy and a mole, who together save a fox and befriend a horse. It’s not a long read and is the type of book that can be either devoured in one sitting or picked up periodically to give your mind some respite. It’s filled with simply stated philosophical ideas such as ‘Is your glass half empty or full?” asked the mole. “’I think I’m grateful to have a glass,’ said the boy.” In these uncertain times, this book reminds us of hope, kindness, and friendship.