On View

What Does Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration Look Like? A Gripping New Show at MoMA PS1 Presents Startling Answers

Many of the works in the show were made by inmates in US prisons.

Many of the works in the show were made by inmates in US prisons.

Taylor Dafoe

Though many of the artists in “Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration,” a new show open now at MoMA PS1, have been convicted of crimes, only in a few cases do we learn the details.

“I don’t talk about guilt and innocence, nor do I talk about why people are in prison, unless that’s important for them in terms of how they understand their art-making,” says Nicole R. Fleetwood, who organized the exhibition of works made from within, or about, the US prison system.

For her, the show is about carcerality as a systemic, not an individual, problem.

“As an abolitionist, if you start playing into the logic of good/bad, innocent/guilty, you start to think about prisons as if they’re about individual decision-making, which is often how we talk about it in a broader normative public,” she says. “Prisons don’t exist because of individual decision-making. They exist as a punitive, harsh way of governing around structural inequality and systemic abuse.”

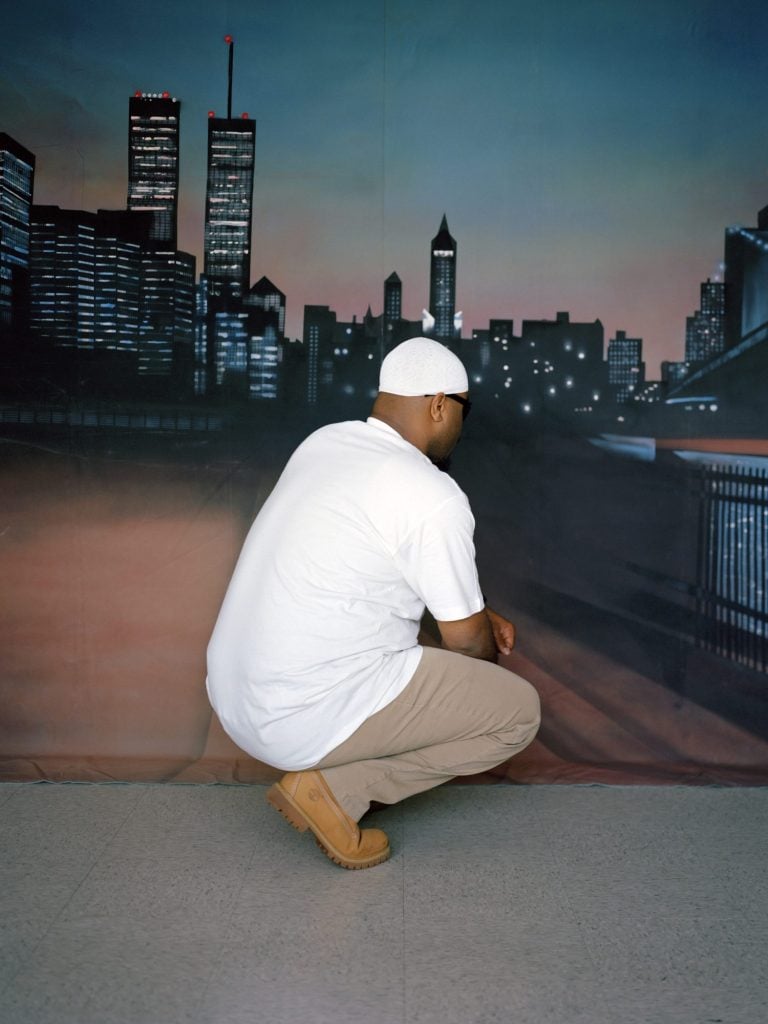

Larry Cook, The Visiting Room #4 (2019). Courtesy of the artist.

“Marking Time” follows Fleetwood’s recently released book of the same name, published this spring, which lays out what she calls “carceral aesthetics.”

“I talk about it as a contemporary, robust movement of art-making that takes place across the carceral state—people in prison, in solitary confinement, on parole, or people who grew up in relationship to carcerality and captivity,” she tells Artnet News.

For artists, it’s a question of overcoming the conditions of their confinement. In lieu of an art supply store, makers turn to bedsheets, hair gel, discarded magazines, and other ephemera to make their work. A six-foot by nine-foot cell represents another limitation, as does the need, in many cases, for creations to be hideable or transportable.

Dean Gillispie, Spiz’s Dinette (1998). Courtesy of the artist.

Thinking about the work in the show through the lens of constraint makes it all the more impressive—sometimes astonishingly so.

For his room-filling tapestry, Apokaluptein 16389067 (2010–13), a dreamy scene of biblical proportions, artist Jesse Krimes meticulously transfer-printed images from magazines onto 39 prison-issued bedsheets.

Another artist, Dean Gillispie, has spent 20 years recreating sculptural scenes from his life using pins, popsicle sticks, and other discarded objects.

Indeed, edenic iconography and the mutability of memory are major themes throughout the show, as is self-portraiture. The prevalence of the latter came as a surprise for Fleetwood when writing the book. It’s perhaps the most common genre of art-making in prison, and skilled portraitists are in high-demand. Inmates—and even prison staff—often commission or trade for a picture of a loved one.

But the art form represents something more than a link to the outside world.

“It’s a way of refuting what I call the criminal index: mugshots, prison ID cards, all the ways photographic images of imprisoned people are used to render them bad criminals. It claims a much more complex humanity,” Fleetwood says.

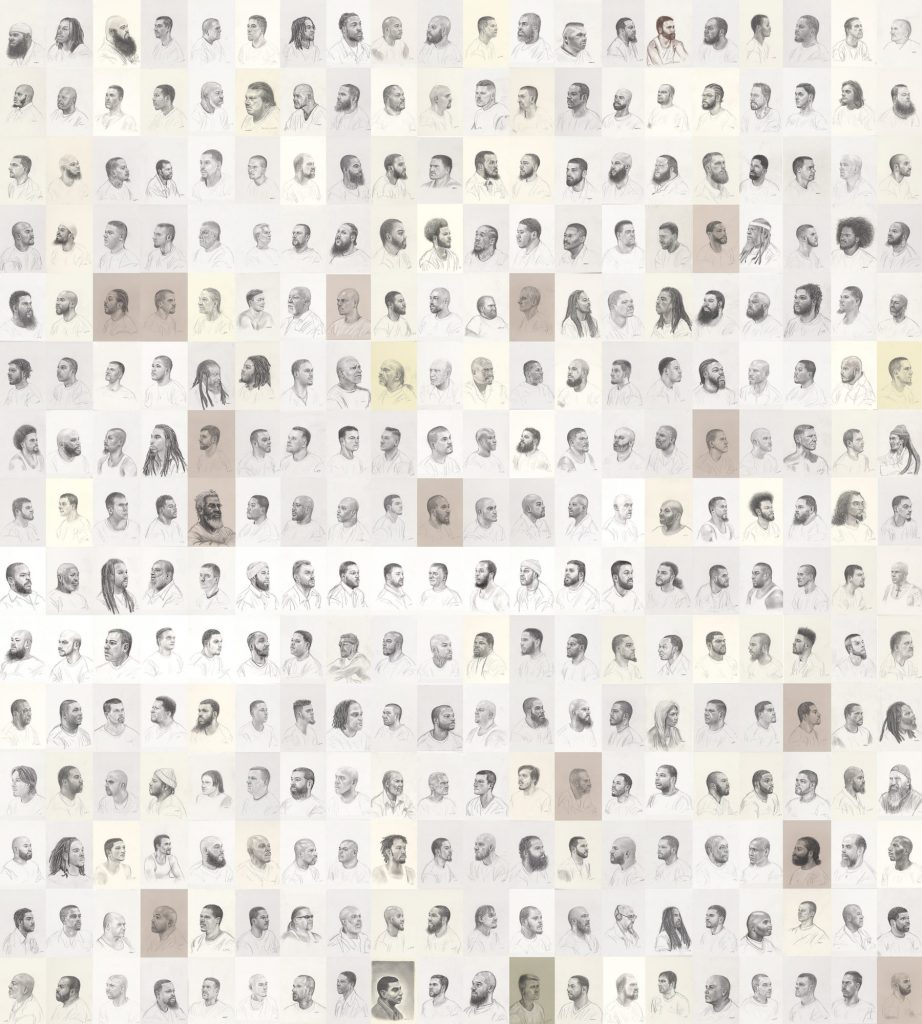

Mark Loughney, Pyrrhic Defeat: A Visual Study of Mass Incarceration (2014–present). Courtesy of the artist.

Pyrrhic Defeat: A Visual Study of Mass Incarceration (2014–present), a sweeping installation of inmate portraits by Mark Loughney, embodies this idea.

The incarcerated artist depicts over 500 of his fellow inmates with remarkable consistency: each portrait is executed in graphite at the same scale. But the pictures never blur into an institutional register, not even when gridded together. The humanity always seeps through.

The most recent portraits in Loughney’s ongoing series find his subjects wearing masks, one of multiple reminders in the show of the pandemic and toll it has taken on the lives of the incarcerated.

Another, more sobering example comes in one of the show’s final galleries, which is filled with paintings and drawings by Ronnie Goodman, who died on the streets of San Francisco in August less than two months before the opening of the exhibition. (“Marking Time” was originally scheduled to open in April.)

Installation view of “Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration.” Courtesy of MoMA PS1. Photo: Matthew Septimus.

Many wondered about the fit of such a show at PS1 because of the institution’s relationship to the Museum of Modern Art, where trustee Larry Fink has been the subject of numerous protests for investing in companies that operate private prisons.

Though PS1 maintains an independent board, the museum has been targeted in demonstrations related to Fink. Last fall, artist Phil Collins withdrew from the museum’s “Theater of Operations” exhibition, while another participant, Michael Rakowitz, demanded that his video in the show be paused in a gesture of protest.

“I’m here and present for those conversations and to do that work within the community to transform these institutions,” she says.

“I don’t think any person or entity should be in the business of making money off of punishment and captivity, period,” she adds. “Profiting from captivity and punishment is, to me, beyond unethical. We should be building an economy that does not allow people to make millions or billions of dollars off of other peoples’ suffering.”