On View

‘Magic Realism Is Our Reality’: Two Hong Kong Artists Reflect on the City’s History of Protest as the Unrest Approaches Its Fourth Month

Dual gallery shows by South Ho and Luke Ching Chin-wai give new meaning to the Hong Kong protests.

Dual gallery shows by South Ho and Luke Ching Chin-wai give new meaning to the Hong Kong protests.

Vivienne Chow

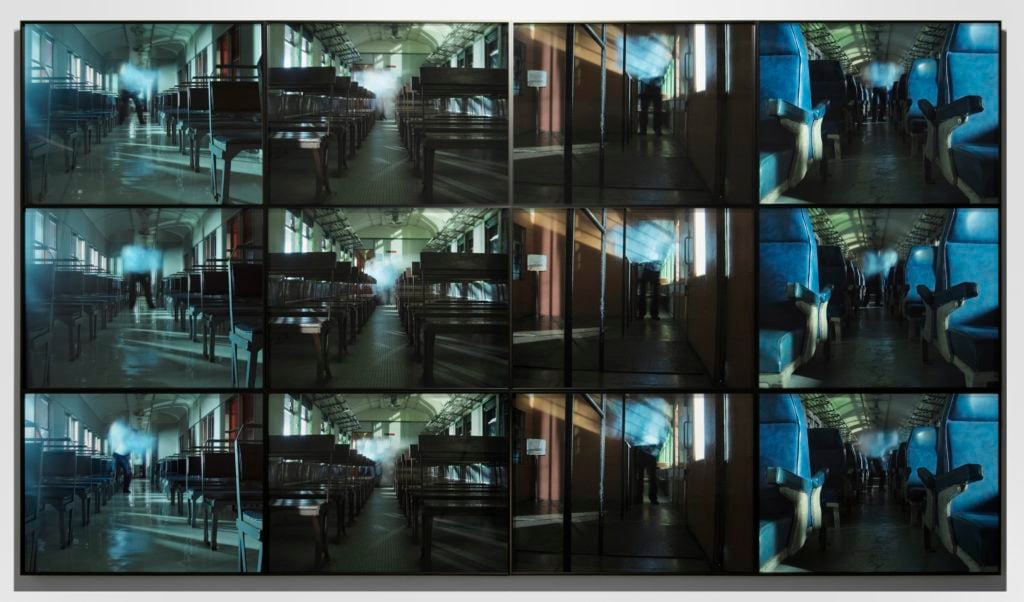

When Hong Kong artist Luke Ching Chin-wai waved his shirt while standing in an old, dimly lit train compartment for a series of photographs taken at the city’s Railway Museum in 2013, he didn’t know that the eerie images would have a disturbing resonance today, a time when police are firing tear gas canisters at protesters inside Hong Kong’s underground stations and beating unarmed civilians in the Mass Transit Railway’s train compartments.

“I wanted to create images that are surreal,” Ching said. Standing in front of Dark Night, White Cloud, the artist recalled how he took the set of 12 photographs using a long exposure technique to visually alter the movement of the shirt waving into an illusion of cloud, mist, or smoke.

“But who would’ve thought these imaginary scenes from six years ago could become real today,” said the 47-year-old artist, referring to the ongoing pro-democracy protests that have been gripping the city since early June. For nearly 100 days, demonstrators have braved the tear gas to rally in the streets, demanding universal suffrage and an independent inquiry into police brutality at the protests, which were sparked by the Hong Kong government’s proposal to extradite suspects to mainland China.

“From the Umbrella Movement [in 2014] to now, we have been unpacking what happened. But we still haven’t come to terms with it yet. And now the [Mass Transit Railway] is not the MTR we used to know. Normal today is not the same as what we were used to. Magic realism is our reality.”

Luke Ching Chin Wai, Dark Night, White Cloud (2013). Courtesy of the artist and Blindspot Gallery.

Ching spoke as he was pacing up and down the floor of Blindspot Gallery, where his solo exhibition “Liquified Sunshine” is being held. The show runs until November 2 in parallel until with “Force Majeure,” a solo exhibition by fellow Hong Kong artist South Ho, who is 12 years older than Ching.

The dual solo exhibition was conceived months ago as a way to bring together two socially-engaged artists from two different generations for a dialogue about the city’s changing sociopolitical landscapes. The ideas was to focus on the artists’ older works, which were inspired by the memories of typhoons, but as Hong Kong became caught in the midst of the biggest social unrest the city has seen since the 1967 riots, the recent civil uprisings have inspired them to create new works. Meanwhile, their past works take on new, almost prophetic meanings.

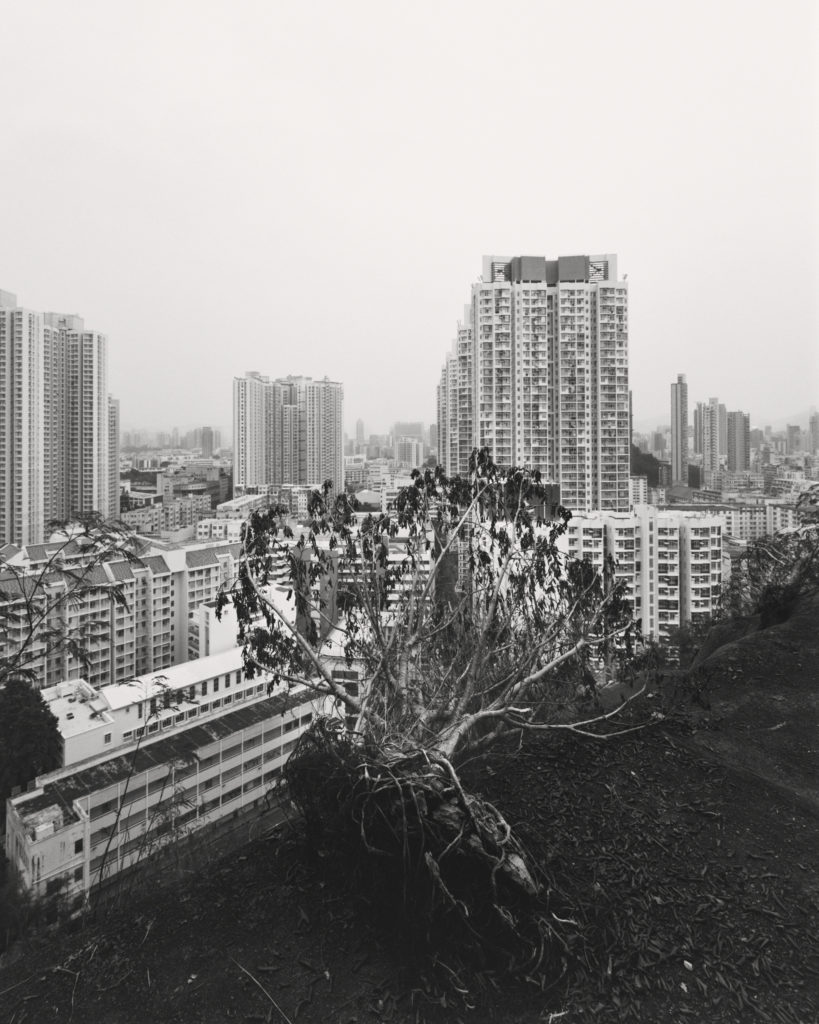

South Ho Siu Nam, Whiteness of Trees III (2018). Courtesy of the artist and Blindspot Gallery.

Echoing Ching’s idea of the new normal is Ho’s photography series “Whiteness of Trees,” hung on the walls at the other end of the gallery. It is a set of 19 black-and-white photographs of the aftermath of super typhoon Mangkhut, which hit Hong Kong last year and was said to be the most intense tropical cyclone the region has ever seen. The government said it caused a record storm surge and more than 1,500 trees were uprooted.

Ho took his camera with him to photograph the uprooted trees and their torn-apart trunks, revealing the inner whiteness hidden beneath their rough skin. “I knew these trees will soon be gone based on how the city is run,” he said, referring to Hong Kong’s efficiency when it comes to cleaning up the streets after a typhoon. But to him, that did not feel right.

“What was not normal was the way people reacted the day after the super typhoon. People were rushing to work as if nothing happened, despite the streets were still full of debris and broken tree trunks. Roads were still blocked,” he said.

South Ho Siu Nam, Whiteness of Trees IV (2018). Courtesy of the artist and Blindspot Gallery.

Pretending to be normal has become the norm since the failure of the 79-day Umbrella Movement. Ho was at the protest sites five years ago documenting the movement, during which people were asking for the right to vote for the city’s leader, unscreened by Beijing. The outcome was Umbrella Salad, his last major body of work prior to “Whiteness of Trees.” The protests did not achieve their goals, but life went on.

“The world was not normal, but people were trying to act normal. It was wrong,” he said. “My works always respond to what happens in the society, from the Umbrella Movement photographs to now. But back then, I never expected how things would turn out today. It is much worse than what I imagined.”

Ho has been back at the protest sites in recent months shooting and filming, and he’s added to the exhibition some of the long takes of the massive protests that have seen millions of people peacefully taking to the streets. Ho wound up getting tear gassed himself on several occasions and, without an eye mask or gas mask, said he had to rely on protesters to help him treat the affected areas. Alongside the videos he has also created an installation made up of colorful rubber balls to mock the so-called “less lethal” sponge grenades, which were fired at the crowd.

“They are called less lethal but they can be lethal if they are used in a lethal way. A photographer friend came from Taiwan to cover the protests and was hit by one of these sponge rounds. He had to leave. Luckily he was safe and had no bone fractures,” Ho said.

Luke Ching Chin Wai, Panic Disorder (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Blindspot Gallery.

The police also refer to the protesters as cockroaches, a tactic used to dehumanize enemies that was borrowed from the Nazis during World War II. In response, Ching’s show includes the cockroach sculptures he made in 2006, along with a new six-minute video work, Panic Disorder, showing his hands making the sculptures, punctuated by flashing images of police.

“Cockroaches are among the most common insects in Hong Kong and you often see them fly around before a typhoon comes. But I’m very scared of cockroaches,” Ching said. “These are made with reference to my imagination of what a cockroach looks like, rather than a real image. We conjure up an image to address our fears. And this is what the police are doing. But their fear is not the protesters. Their fear is the deed they do, to beat unarmed protesters with excessive force. They have to dehumanize them to justify their violent actions.”

The ongoing political crisis has brought Hongkongers face to face with what they have refused to acknowledge in the past, Ching said: “It’s like unravelling all the dirt hidden beneath a carpet.”

He related this to his exhibition’s title work, Liquefied Sunshine. Conceived between 2014 and 2015, the installation is made up of 721 postcards of views of Hong Kong under a clear blue sky, but painted over with lightly-colored brushstrokes that look like rain.

Ching questioned why nearly all the postcards he came across had sunny views of the city, despite the frequency of rain in Hong Kong’s humid, sub-tropical climate. “These postcards tell us that sunny days, blue and clear skies are an order. Rain, however, has been deemed as a distortion of such an order,” he said.

Installation view of “Liquefied Sunshine” (2019). Courtesy of the artists and Blindspot Gallery.

In light of the the protests, Ching’s rainy scenes are given a new meaning. “I hand-painted the rain with single individual brushstrokes. Rain is made up of drops of water, just like protests formed by groups of individuals disrupting certain orders in the city,” Ching said, looking intently at the wall of postcards in front of him. “And now I don’t see how this rain will ever stop.”

“We are facing a much bigger shakeup compared to five years ago. We are confronted with what kind of future we want for Hong Kong, and it seems that we have never been so clear about it,” Ho said, holding a transparent shield made of roofing panels that he modeled after those used by riot police.

“There is a delicate balance of Hong Kong that must be maintained. It cannot be one country, one system. But it cannot go against Beijing’s will. There must be checks and balances, otherwise Hong Kong will collapse,” he said.

Ho banged the bottom edge of the shield on the floor, just like the riot police do on the front lines of protesters. He yelled out to the exhibition goers: “Stop charging at artists!”