Art World

How Galleries Are Increasingly Funding Museum Shows

Museums need support from galleries, but is it only blue-chips landing the best partnerships?

Museums need support from galleries, but is it only blue-chips landing the best partnerships?

Jo Lawson-Tancred

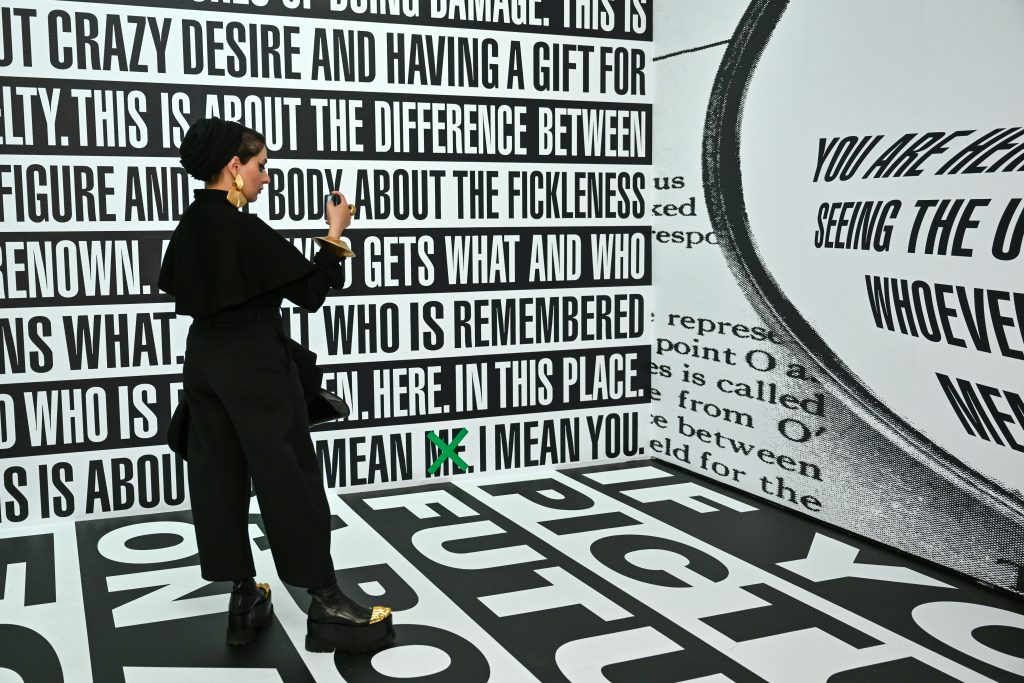

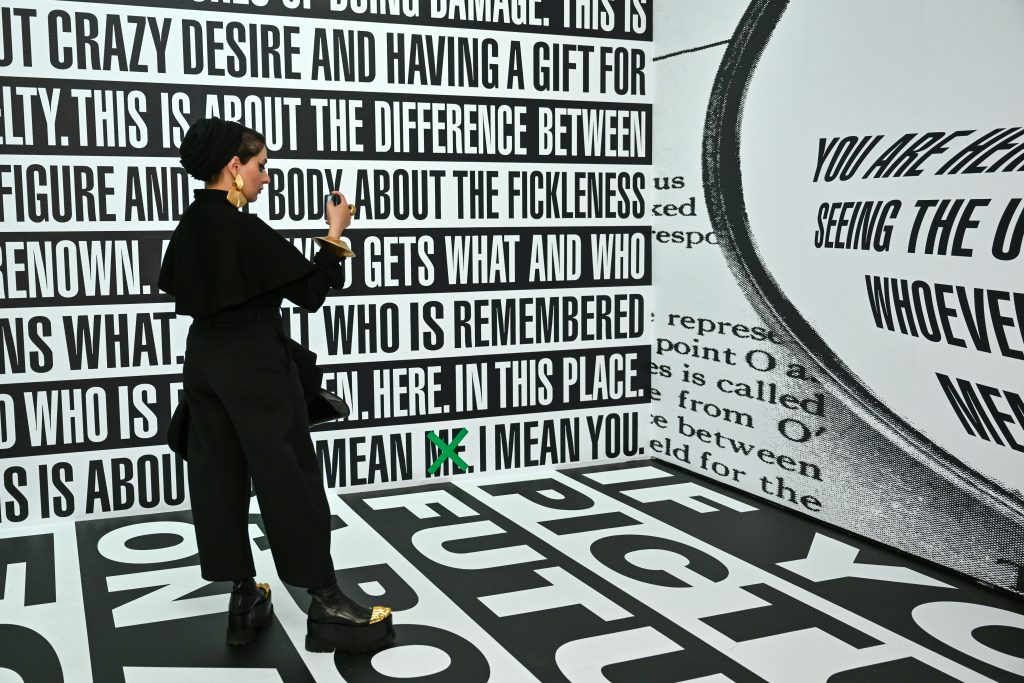

Barbara Kruger’s first institutional show in London in over two decades, on view at the Serpentine Gallery, has been a smash hit with audiences and critics alike. Any collectors who have had their interest piqued by the American artist’s work after seeing the show will be pleased to hear that Sprüth Magers, one of the exhibition’s two gallery sponsors, is opening its own Kruger show at their London premises on April 12, just three weeks after the Serpentine’s closes.

Those who keep a close eye on the art world’s calendar of events will know that the advantageous alignment of commercial shows with institutional shows is commonplace. But, increasingly, gallery sponsorship of museum shows has become de rigeur. Some recent examples, of many in London, include Victoria Miro’s presentation of new work by Isaac Julien last May, coinciding neatly with an exhibition at Tate Britain that the gallery supported. Goodman Gallery is currently giving Zineb Sedira her London debut, timed to a Whitechapel Gallery show it is sponsoring. Alison Jacques’s new Monica Sjöö show just overlapped with a major retrospective the gallery supported at Modern Art Oxford.

Even a decade ago, such partnerships would not have been made as visible, suggesting that there is a growing acceptance of the practice. Nevertheless, sponsorship deals remain decidedly confidential to maintain an air of distance between the market and museums.

Isaac Julien’s exhibition at Tate Britain in 2023. Photo: Judith Burrows via Getty Images.

“It would be unusual for an exhibition of a contemporary artist or modern estate to take place without collaborating in some way their market representative,” said Thomas Marks, co-founder of Marks|Calil strategic consulting firm. Museums still have to think “about the ethics of accepting money from galleries that have a financial interest, but the fact is that most artists that have galleries rely on them for infrastructure and administration.”

Depending on the artist, the venue, and the backing gallery, sponsorship deals can range from a few grand to hundreds of thousands of dollars. A major gallery gave as much as a quarter of a million pounds ($317,000) to support an exhibition of one of their artists at an esteemed institution in London, according to an anonymous source. The institution declined to comment, as did all museums contacted for this article.

At the very least, sponsorship opportunities may be hard for museums to pass up, especially as public funding continues to plummet across the U.K. and Europe, and institutions may not want to be accused of compromising their curatorial independence by accepting much needed assistance.

Most sponsorship deals, however, are not just be a lump sum of cash. Instead, a gallery may front the cost for a dinner or related event. Additionally, they may help pay for the production of a catalog since a gallery tends to house the best library of high-resolution imagery, archival texts, and other background materials on each of its artists.

Installation view of Anish Kapoor, <i>Sky Mirror</i> (2018) in Venice in 2022. Photo: David Levene, courtesy of Lisson Gallery, © Anish Kapoor.

Galleries are also key in building relationships for museums. They might make advantageous introductions to relevant collectors who could become generous museum patrons. More importantly still, an artist’s gallery is usually the main channel by which museums can secure prize loans from private collections.

Lisson Gallery has helped facilitate and financially support major exhibitions for both its biggest stars, such as Marina Abramovic’s recent blockbuster at London’s Royal Academy, and its mid-career artists like Yu Hong, who was the subject of a U.S. survey at the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) Museum of Art.

Immediately after an artist is approached by a museum, “our role is to make sure the crucial dialogue between a curator and an artist is as easy and fruitful as can be,” said Greg Hilty, a partner at Lisson. “If things are going well, we simply sit in the background. We tend to know everything that’s happening and can answer questions very quickly.”

Once an exhibition is confirmed, the gallery steps up its involvement, as was the case with an Anish Kapoor exhibition at the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice in 2022, for which Lisson helped land a mammoth sponsorship deal with LG’s OLED screens.

“When we can mobilize our network of contacts, we certainly do,” said Hilty.

Though there are clear financial benefits to commercial gallery sponsorship, some industry insiders fear museums are too easily lured by the bigger budgets of blue-chip galleries. Not only can mega-galleries provide a higher level of sponsorship than smaller dealers, but with larger teams they can cultivate larger institutional networks through which to promote their artists.

What a smaller gallery may lack in cash, however, it makes up for in administrative labor, according to independent dealer Kristin Hjellegjerde, who founded her eponymous gallery in London in 2012 and now has outposts in Berlin and West Palm Beach. She mainly works with emerging and mid-career artists, and the gallery has put huge resources into providing them with a strong institutional presence.

“If a museum show is going to happen, they need the whole board to say yes,” she said. Aware that smaller galleries might not be thought of as being able to contribute to a successful show, she added, “I’ve said to museums, we’ll do what a big gallery can do in terms of shipping, loans, and securing contributions from other sources.” Last autumn, a quarter of the 51 artists on her roster were in museum shows.

Star (2022). Design and concept by Soheila Sokhanvari, technical design by Jflemay Architect and Design. Photo: Max Colson, courtesy of the Barbican.

For the Barbican’s Soheila Sokhanvari exhibition in 2022, the gallery helped the museum source 28 artworks from 28 different collections on top of helping fund the construction of an eye-catching new mirrored installation, Star, custom made for the show. When it traveled to ARoS Aarhus Art Museum in Denmark, the gallery took on the hassle and expense of shipping each work to London, giving the museum the more convenient option of shipping everything from one place.

The gallery is also a named sponsor of the Dulwich Picture Gallery’s current exhibition, “Soulscapes,” in which works by two of Hjellegjerde’s artists—Kimathi Mafafo and Nengi Omuku—are featured.

“I didn’t have to give that money [to the institution],” she explained, adding that the sum she donated for exhibition costs equated to about a year of Dulwich Picture Gallery’s Patron scheme, which can range from £1,250 to £10,000 ($1,500 to $12,500) annually. “It’s being a patron like a lot of other people are a patron,” she said.

The institutional advocacy a gallery can offer is often a big draw for artists and their estates, and is one of the reasons “my artists stay with me for a long time,” Hjellegjerde said.

Hilty agrees and cited as an example the recent Leon Polk Smith retrospective at Haus Konstruktiv in Zurich, one of the late artist’s few institutional outings in Europe. The museum approached Lisson Gallery, aware it had announced representation of Smith’s estate in 2017.

Exhibition view of Leon Polk Smith “Beyond Space” at Haus Konstrukiv, Zurich , 2023. Photo courtesy of Haus Konstruktiv, © Leon Polk Smith.

“They were not 100 percent sure it would work, so we put them in touch with the foundation and started a dialogue,” said Hilty. “Smith is a highly regarded artist in America but less known in Europe. Being a global gallery with a big European presence, the fact that we chose to represent him made that connection more likely.”

“It’s that kind of network of information initially, and then communication and support that leads to good projects occurring,” he added.

Ultimately, galleries, museums, and artists are dependent on each other, according to Marks: “There are genuine collaborative opportunities to ensure work reaches a wider public and is positioned critically, in a way that a straightforward market show would be unlikely to do.”