Art World

We Asked Leading Video Artists How Best to Enjoy the Medium—and, Yes, It’s OK to Leave in the Middle (and to Be Confused)

Don't be put off by the long runtimes, uncomfortable seating, or a lack of narrative.

Don't be put off by the long runtimes, uncomfortable seating, or a lack of narrative.

Melissa Smith

Video art has been around for a long time. But in the 1980s, when artist Coco Fusco was just starting out, it was “not the stuff of mainstream museums,” For a long time, there wasn’t much of a market for video art either, and Fusco earned money selling her work to educational distributors.

Video artist Stan Douglas noticed a turning point in the early 90s, especially after Documenta 9 in 1992, when “suddenly you see video art seen in context with painting and sculpture,” he said, “and being of equal value.”

Even so, a video artist getting that type of institutional support was “more the exception than the rule,” Fusco said. And commercial galleries tended to support a very specific type of work: pieces where “you couldn’t have dialogue—or only minimal dialogue,” Fusco explained, “or either short or tableaux-like things that looked like slow-moving murals.”

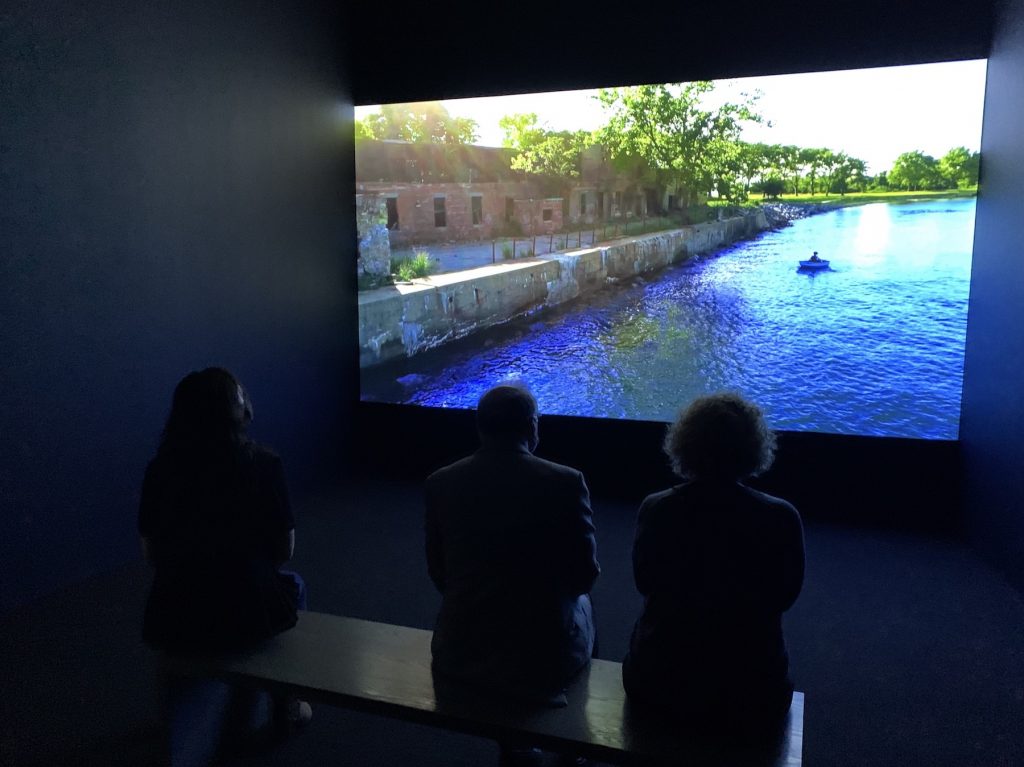

Coco Fusco, Your Eyes Will Be an Empty Word (2021). Photo by Ben Davis.

Nowadays, Fusco has finally noticed “a change of heart in the art market when it comes to video.” Institutions—and some collectors—are more willing to acquire, show, and invest in a wider variety of video art.

Biennials have become the unofficial domain of video, often showing the broadest range of work. There were a number of video pieces in the most recent Whitney Biennial, including Fusco’s Your Eyes Will Be an Empty Word (2021), her 12-minute rumination on Hart Island east of the Bronx, where New York City buries unidentified dead bodies.

With more curatorial interest in video, even “artists who weren’t making video are utilizing it in some way,” said interdisciplinary artist Jibade Khalil Huffman. He hopes the medium’s growing prominence will help visitors become “less resistant to or less tied to their own feelings [about video work].”

We might know how to look at a Jackson Pollock painting—taking in the whole composition, then zooming in on specific details. But when presented with an equally abstract video, it’s tempting to just walk away.

So we’ve asked artists to provide some tips on how to engage with the different types of video art cropping up. Here are their recommendations.

First, it’s worth pointing out the preconceived notions viewers often have about video art: They tend to get very hung up on its length. Paintings and sculpture are static. Videos are not. Viewers then feel pressure to sit through the whole work—be it 2 minutes, 12 minutes, or 1 hour (or more).

“The whole problem in art these days is about getting people to pay attention at all,” Fusco said. “If you walk through the permanent collection at MoMA or something, you see people are just wandering and not looking at paintings for very long either.”

Stan Douglas, film still Doppelgänger (2019). © Stan Douglas. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro, and David Zwirner.

So while it’s unmistakable that video art suffers more from the inattention economy, artists are divided on how important it is for viewers to watch for the duration. Douglas—who is currently representing Canada in the Venice Biennale with a piece that includes a video exploring how different forms of rap music can act as both a balm and gesture of revolt in times of social and political unrest—feels that viewers shouldn’t approach video art the same way they do videos in other contexts.

Narratives within video art that have “a beginning, middle, and end don’t make sense in a place [like a museum] where somebody walks in and out randomly,” he said. A museum viewer’s “relationship with time is quite different,” he added. “It’s not linear, like going to a movie or watching a video on a TV or Netflix or something.”

Douglas tends to bypass this expectation altogether by “making works that are so long,” he said, “that you can’t possibly see the whole thing anyway.”

The media landscape shapes video art as much as the other way around. And artists are very aware of this fact.

“We live in a different world in terms of the presence of the moving image from the world that I grew up in, there’s screens everywhere you go,” Fusco noted, “and when I talk to my students, the young ones are obsessed with this idea that they are unlike anybody else in the history of the world because they have grown up with phones. They’re fixated on a kind of viewing of the moving image that is like scrolling.”

Video artists are, either directly or indirectly, influenced by this.

Ja’Tovia Gary, The Giverny Suite (2019), at ZOLLAMT MMK, Frankfurt, 2021. © Ja’Tovia Gary, courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Albrecht Haag.

Like a lot of artists, Ja’Tovia Gary feels less inclined to define her work by strict categories. Her breakout video, The Giverny Document (2019), which brings together animation, archival footage, on-the-street interviews, and scenes of Gary herself in Claude Monet’s garden in France. For Gary, “the line blurs between video art, cinema, and object-making, and I see the films oftentimes as sculptures,” she said. “There may be an element of the film that feels like a video art piece; there may be an element that feels like a music video; there may be an element that feels like a regular documentary.”

Gary said she feels as though “social media is in some ways bleeding through and influencing these methodologies that I’m using.” In a similar way, “a lot of young people online are pushing these boundaries and blurring these definitions, and so that can’t not influence what the contemporary artists are doing.”

Gary doesn’t let these trends influence the overall length of her finished work. But a shorter version of a piece circulated online “might be a hook,” she said, “for people to understand that they might need to sit longer than 30 seconds and watch something unfold over time.”

Like Gary, artist Jamilah Sabur considers her video work “in the same way I would think about presenting a sculpture or something that’s three dimensional,” she said. “I think about the experience.”

She, for one, is less concerned by how long viewers engage with it, focusing instead on getting them to move or navigate the space in a certain way.

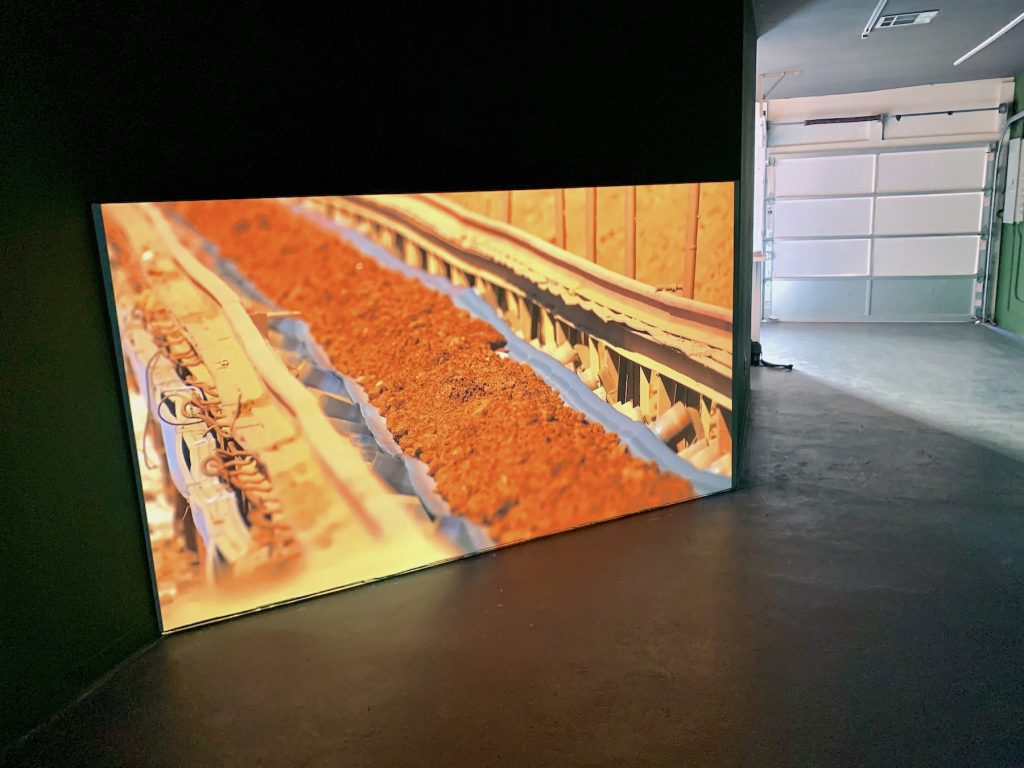

Installation by Jamilah Sabur at the Prospect.5 Triennial in New Orleans. Photo by Ben Davis.

For Bulk Pangaea (2021), her video installation that she created for last year’s Prospect.5 Triennial, Sabur used various film stills to explore the history of nations associated with aluminum’s trade routes. She describes her approach as “closer to choreography,” with “the screens creating an active experience in a way that you’d experience a dance.”

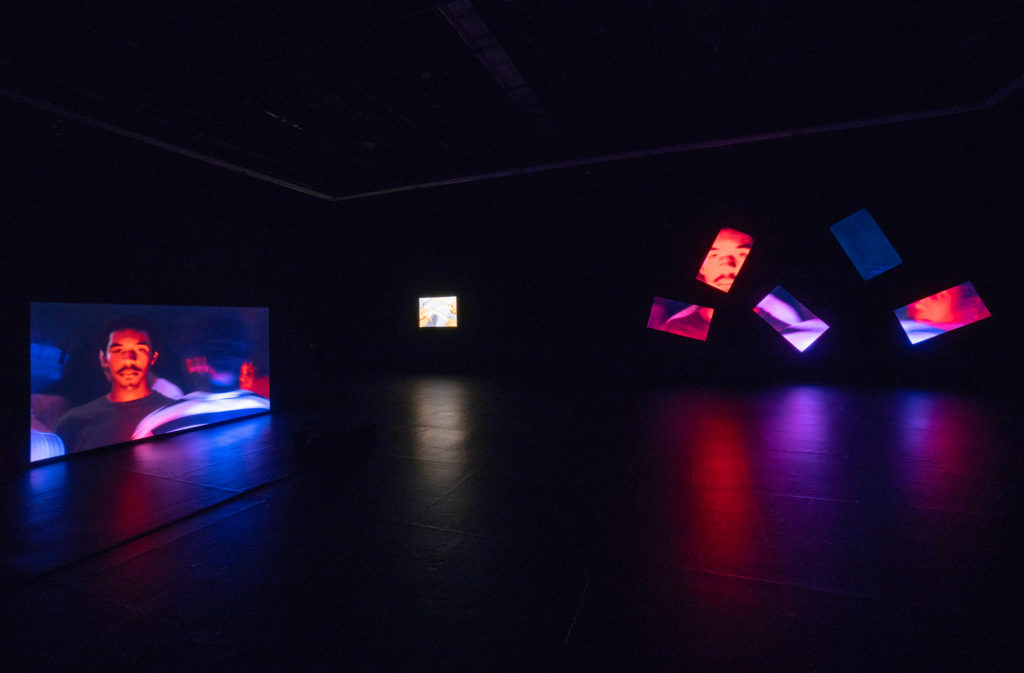

Many other artists agreed the entire environment is part of the work. Jibade Khalil Huffman tends to make videos consisting of shorter loops, with a main video channel accompanied by a soundtrack that can be heard throughout the entire space and perhaps even text that one might sit and read. “Viewers can pop in and out [of each part] in the same way that you do with collage or a painting,” he said.

In that way, Huffman explained, he doesn’t need viewers to experience the whole thing in one go, “in the same way that Kerry James Marshall doesn’t need me to go and stand for a minimum of, say, 45 minutes in front of one of his paintings.”

Douglas recalled that he was once asked: “So what do you do, Stan: rugs, carpets, or benches?”

Installation view of Jibade-Khalil Huffman’s show “Tempo” at the Kitchen, New York. Courtesy of the artist and Anat Ebgi.

While an artist as successful as Douglas probably has his pick of how to make his audiences comfortable, it’s clear that is not always the case with video art presentations. Reading between the lines a bit, an unspoken tip artists would give visitors as a result is: stick with it anyway.

Because even though there may be “more video art around,” Huffman said, “that doesn’t necessarily mean that the conditions for making it have gotten better.”

It’s still not consistently financially supported, and a commercial gallery is not an ideal setting for showing the work. Most are “white boxes with cement floors,” noted Fusco, which makes them “the worst nightmare for presenting video.” On top of that, galleries and museums often have “awful acoustics,” she continued.

In the end, artists are trying to figure out how to reach viewers. Ultimately, they want you to surrender “to an aesthetic experience,” as Fusco put it, that they know may “not be an easy one.”