People

‘He Was an Immense Artist’: The Chinese Artist Huang Yong Ping, Who Fused the Spirit of Duchamp with Zen Buddhism, Has Died

The France-based Chinese artist fell foul of the censors in China and animal rights activists in North America.

The France-based Chinese artist fell foul of the censors in China and animal rights activists in North America.

Kate Brown

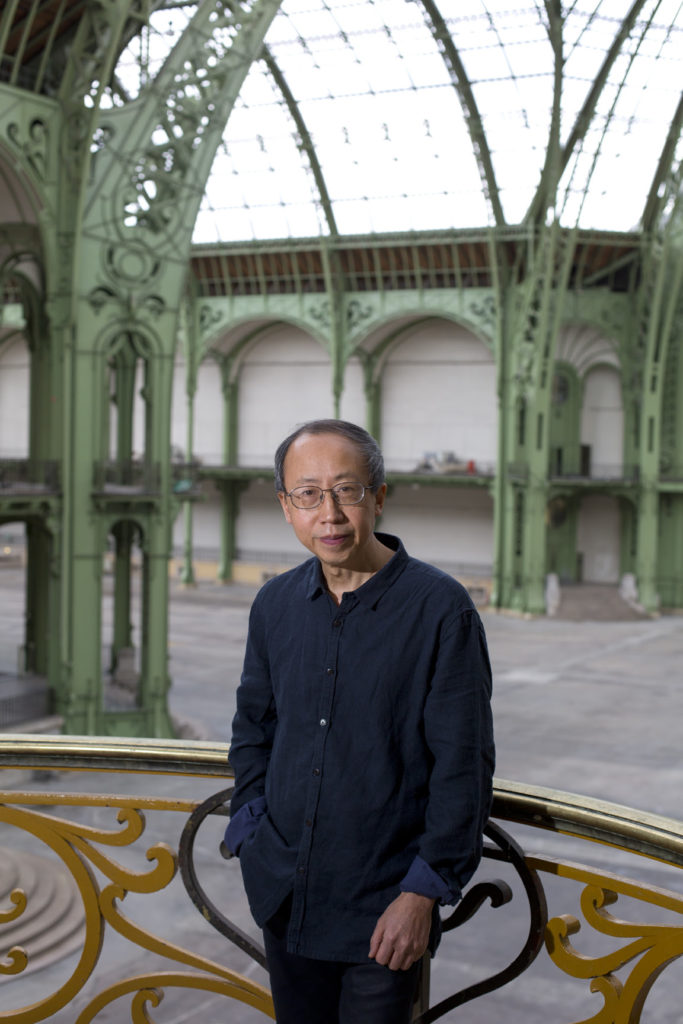

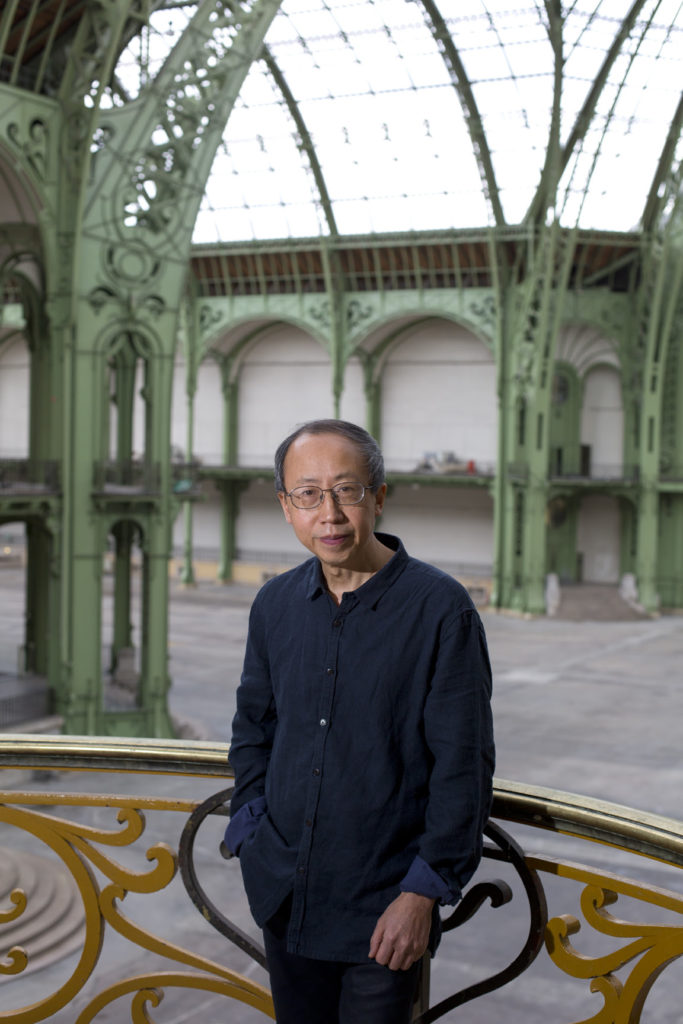

The France-based, Chinese artist Huang Yong Ping, who was known for weaving Chinese and Western historical canons together to create provocative results, died suddenly on Saturday. The pioneering member of the Chinese avant-garde was 65 years old.

Born in 1954 in Xiamen, China, Huang was a founding member of the Xiamen Dada group. The collective first came to attention when in 1986 they torched a number of the paintings they had recently shown at the Xiamen People’s Art Museum. The radical act was prompted by their dissatisfaction with the circumstances around the show. The collective’s motto was “Zen is Dada, Dada is Zen,” and Huang’s hero was Marcel Duchamp.

Over the following decades, Huang continued to fuse elements of Zen Buddhism, Dadaism, and a Duchampian sense of irony to create large-scale surrealistic installations and sculptures, some of which fell foul of political censorship in China, while one notorious work upset animal rights activists in North America.

“Huang Yong Ping was a giant of the avant-garde, a father figure for generations of artists and thinkers,” the Paris-based art dealer Kamel Mennour told artnet News. “He opened up the delicate path of the dialogue between worlds with intact engagement and philosophical view on the world’s turbulences,” Mennour said, adding, “He was an immense artist. He was my friend.” The dealer began formally representing the artist a decade ago by which time Huang was already settled in Paris.

The self-taught artist, who numbered Joseph Beuys, John Cage, as well as Duchamp as inspirations, maintained a critical position and cast a skeptical eye on a rapidly globalizing world, which his career personified.

In 1987, he made what would become an iconic work, The History of Chinese Painting and the History of Modern Western Art Washed in the Washing Machine for Two Minutes, by destroying art history books by Wang Bomin and Herbert Read in the laundry. The artist placed the resulting pulp atop of piece of broken glass on a Chinese teabox.

In 1989, Huang traveled to Paris to take part in the groundbreaking Centre Pompidou exhibition “Magiciens de la Terre.” He stayed in France, which he went on to represent at the Venice Biennale in 1999. For his prestigious Monumenta commission in 2016, he filled the Grand Palais in Paris with a giant, serpentine sculpture and shipping containers to create Empires.

It would not be the last time his work, which often featured animals, was pulled from a major exhibition. In 2018, Huang’s Theater of the World was heavily modified by the Guggenheim Museum after vehement protests from animal rights activists. A petition to take down the title work and two other pieces from the group show “Art and China After 1989” garnered half a million signatories within days.

In Huang’s work, caged snakes and lizards were meant to devour insects, and probably each other, during the show. The Guggenheim showed the artist’s sculptural cage without the animals.

In an interview with artnet News’s editor-in-chief, Andrew Goldstein, Guggenheim director Richard Armstrong described Huang as an artist “asking tough questions, and that is brutal.” New York’s Gladstone Gallery, which also represents the artist, put up a show of Huang’s work following the museum’s decision.

Huang maintained that he was against provocation for its own sake, asking: “How can an artwork be created just to be censored?” His Theatre of the World was shown as the artist intended at the Guggenheim Bilbao but only as an empty cage at SFMOMA.