Archaeology & History

The Hunt: How the Ancient City of Troy Was Found (and Nearly Destroyed)

Explorers had searched for years for the possibly mythical, possibly real city.

Over a few short months in 1871, Heinrich Schliemann achieved a task that had eluded literature’s fiercest ensemble of warriors: he breached the supposedly impregnable walls of Troy. To do so, the Prussian entrepreneur used the full toolkit of 19th-century industry, hiring a railway engineer to dig a 45-foot trench and then deploying TNT. Take that, Agamemnon.

Today, Schliemann is a divisive figure, begrudgingly admired for pinpointing the elusive hilltop city in northwest Turkey where the perhaps-mythical, perhaps-historical Troy was located, but derided for the destructive methods he employed to reach such an end. Schliemann was no book-bound archaeologist, and his triumph at Hisarlik, as the site is known today, was guided by the same headstrong bravado that had characterized his wildly successful business career.

The access ramp (1800-1275 B.C.E.) of Homeric Troy. Photo: DeAgostini/ Getty Images.

Growing up impoverished, Schliemann couldn’t afford to attend university and began work aged 14, finding employment first as a grocer and then as a cabin boy aboard an ill-fated brig bound for Venezuela. Schliemann washed up, almost literally, in Amsterdam. There, he rose through the ranks of an import/export firm before setting out on his own, trading Indian indigo, Scandinavian herring, Californian gold, and weapons that fueled the Crimean War.

A multimillionaire by his mid-30s, Schliemann retired and devoted himself to proving that Homer’s Troy was a historical place and not just a poetic fantasy. First, though, he needed to obtain a divorce and find his Helen. An Athenian archbishop played matchmaker, seeking out a Greek woman who was young, beautiful, and filled with the “Homeric spirit.” Her name was Sophia Engastromenou, and after marrying her in 1869, he decamped to the Troad, the region surrounding Troy, which he would frequent for the next two decades.

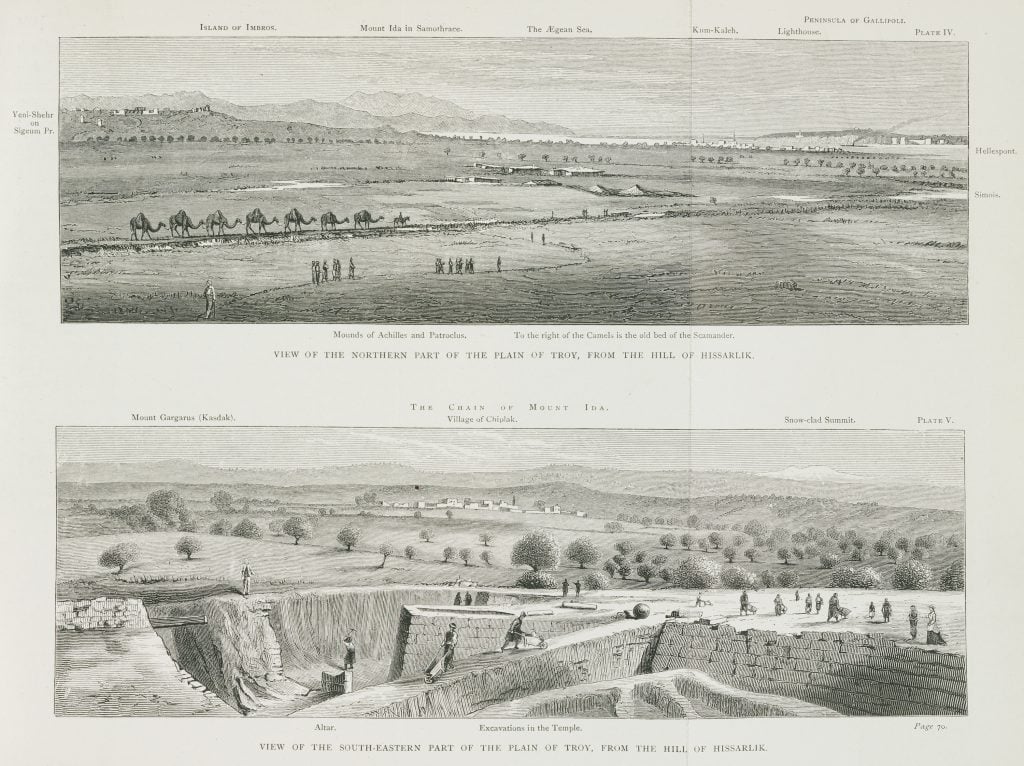

Two contemporary prints (1871-75) showing the site at Hisarlik. Photo: Getty Images.

In Schliemann’s own mythology, his obsession with finding the lost city reached back to boyhood. He recalled encountering an image of the city in flames in a children’s book and learning the Iliad’s sanguine lessons at the knee of his father. Alternatively, it was a chance encounter in Athens with Ernst Ziller, a member of an unsuccessful 1864 excavation, that proved inspirational.

For more than 150 years, rediscovering Homer’s Troy had obsessed fastidious scholars and romantic travelers alike, and Ziller’s expedition had centered on the latest site of speculation: the hill at Pinarbasi, also on Turkey’s northwestern coast. When Schliemann arrived at the far reach of the Ottoman Empire, however, Frank Calvert, an English expatriate, convinced his fellow enthusiast to focus instead on a site a few miles to the north. Calvert owned a plot of land on the hill and had seen his surveys favorably published in academic journals. The problem? He was short of cash.

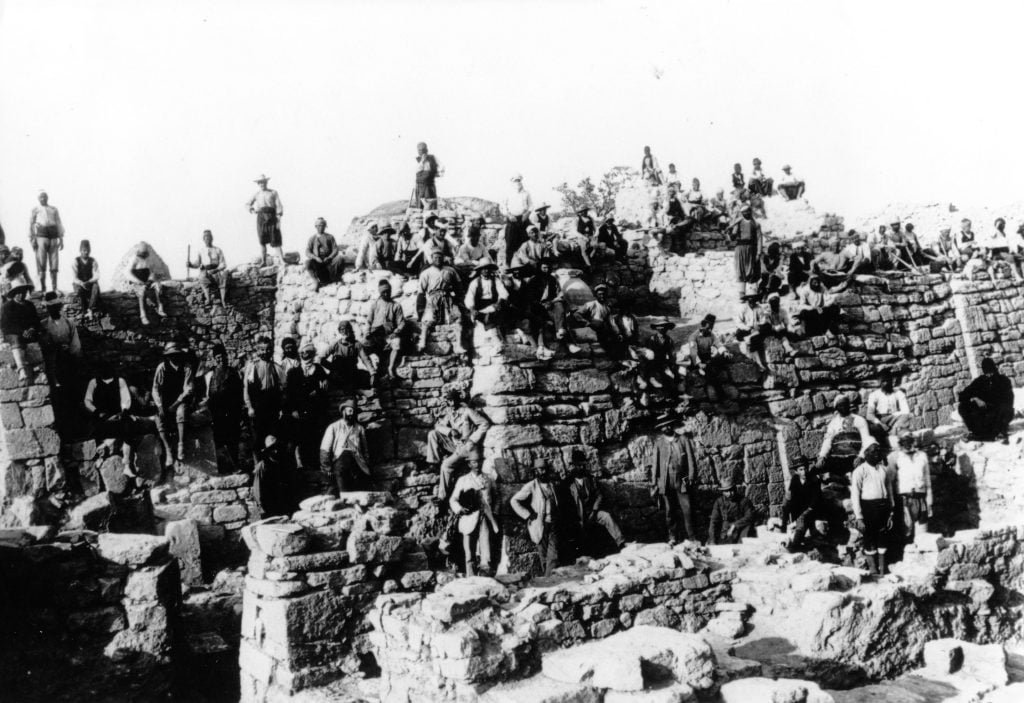

Heinrich Schliemann in Troy alongside his workers and excavators. Photo: Getty Images.

Brilliantly positioned, overlooking the Hellespont with a lagoon providing protection for passing ships, Hisarlik, Calvert argued, was the ideal site for a Bronze Age trading port, and its steep terrain and windswept plain matched Homer’s descriptions. Schliemann was convinced and in no mood to wait for official permission.

Schliemann believed that the Troy ruled over by King Priam, as in the Iliad, would be found at the deepest layer of the city, and so, beginning in 1870, he aimed for the base of Hisarlik’s mound. He worked fast, employing 150 workmen and teams of carts that ceaselessly carried debris away on a rail line. He uncovered a city protected by two lines of defense, with stone ramps leading to a citadel that showed the tell-tale signs of destruction by fire.

Inside stone-lined boxes, he found a cluster of jewels (gold, carnelian beads, lapis lazuli, amber) which he named Priam’s Treasure and a hoard of gold rings and diadems which he named the “Jewels of Helen.” Next, he smuggled his booty back to Europe, photographed Sophia “Helen” Schliemann decked out in the plundered swag, and spread his news far and wide: he had found Troy.

Sophia Schliemann with the gold jewelry found in Troy. Photo: Getty Images.

Even at the time, Schliemann’s triumphalism was met with cynicism. Today, the 55-foot mound is understood to contain nine Troys, spanning from an early Bronze Age settlement in the third millennium B.C.E. to a Byzantine complex from the 13th century C.E. It tells the story of a city whose fortunes rose and fell in cycles before its ultimate desertion. The layer Schliemann hit upon dated to 2400 B.C.E., roughly 1,000 years prior to Homer’s Trojan War. Schliemann indeed found the fabled city, but he obliterated it in the process.

Despite his folly, when it comes to misreading the ruins of ancient Troy, Schliemann stands in excellent company. Beginning in the 7th century B.C.E., Troy became an ancient tourist site, with pilgrims arriving to venerate its memory. Xerxes the Great did so before invading Greece in 480 B.C.E., and Alexander the Great followed suit when invading Persia in 334 B.C.E., each one mistaking the city’s mounds and Neolithic graves for the tombs of Homeric heroes.

The Hunt explores art and ancient relics that are—alas!—lost to time. From the Ark of the Covenant to Cleopatra’s tomb, these legendary treasures have long captured the imaginations of historians and archaeologists, even if they remain buried under layers of sand, stone, and history.