On View

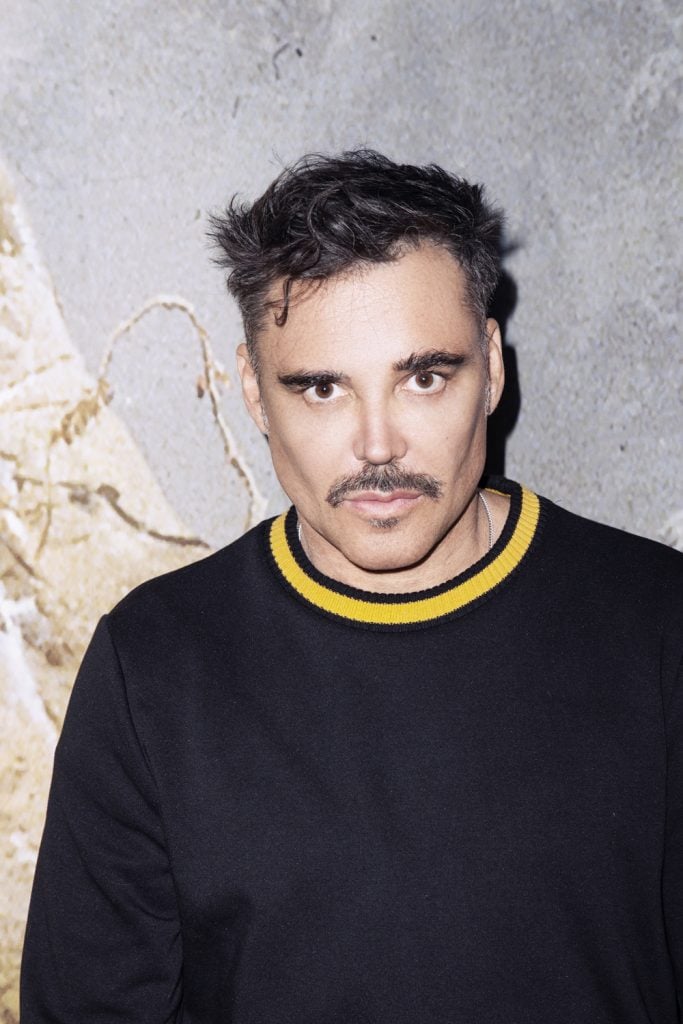

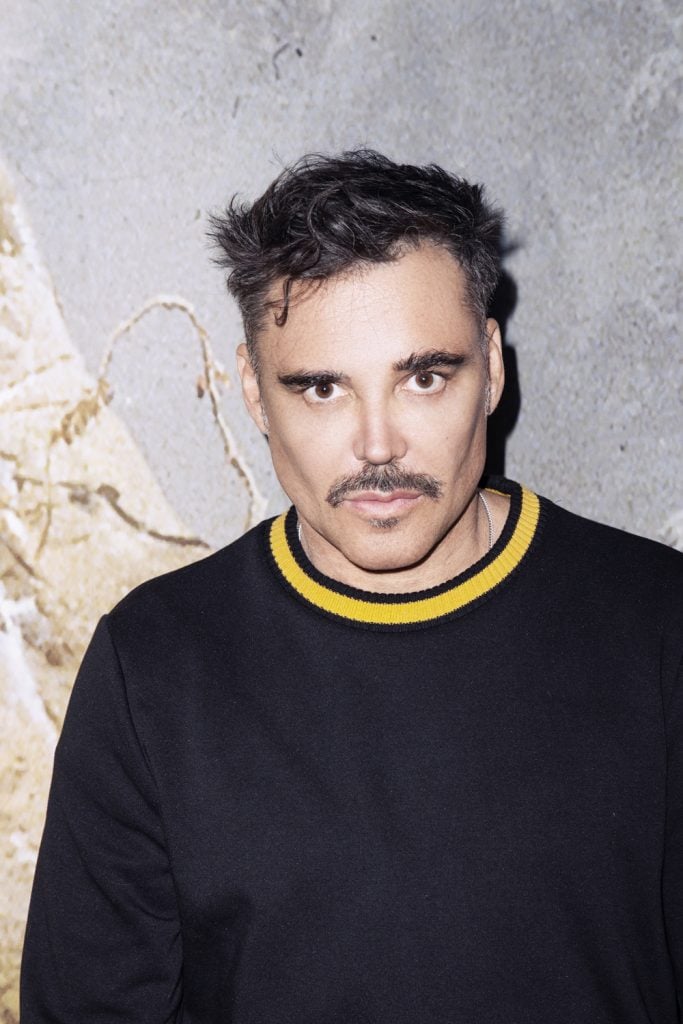

‘I Want to Make Pictures That Mean Something’: David LaChapelle on Turning Away From Celebrity Portraits to Create More Enigmatic Images

The photographer's largest retrospective ever is on view at Fotografiska New York.

The photographer's largest retrospective ever is on view at Fotografiska New York.

William Van Meter

Earlier this week, David LaChapelle was giving a preview tour of his new exhibition to a small press cadre. He passed a wall of iconic big-budget glamour images that hung in chic cobalt-painted frames. The vamping models in heavy makeup were out-of-step with today’s post-2020 fashion landscape—and apparently with the photographer himself.

“Those are just fashion images they don’t mean anything,” he said, dismissively waving his hand, and without pausing lead the group to the next room.

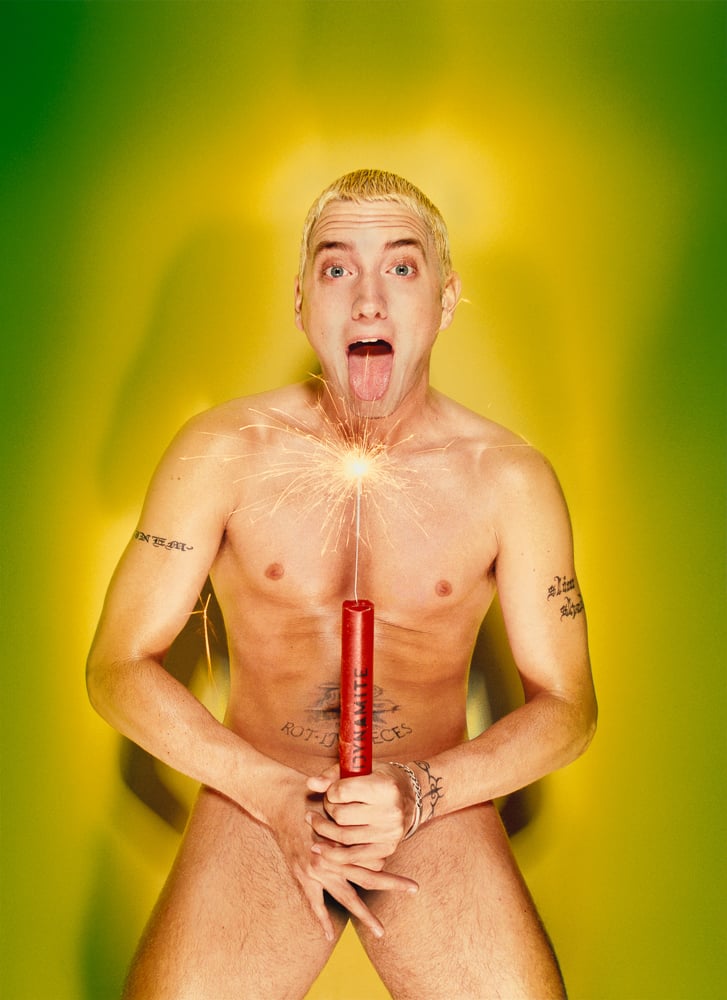

Eminem: About to Blow (1999, New York), a detail from LaChapelle’s Vox Populi wheatpaste poster installation. Photo: ©David LaChapelle, courtesy of Fotografiska New York.

LaChapelle is best known as a celebrity photographer nonpareil. His shoots are high-concept (and high-budget) with lurid colors that pop like Skittles. The retrospective “Make Believe,” which opens today at Fotografiska New York, is a reminder that there is much more to LaChapelle than his Hollywood forays, and that he is in fact, a lot more interesting when he veers away from the glitz.

Yes, there are cameos by Madonna, Lizzo, and Tupac in the show. But the exhibition utilizes the minimum of his vast celebrity fodder in the more than 150 works spread across Fotografiska’s five floors. It is the artist’s first solo New York museum outing and his largest-ever exhibition, and showcases work from 1984–2022.

Good News for Modern Man II (1984, New York). Photo: © David LaChapelle, courtesy of Fotografiska New York.

The show makes the argument that there is a vast difference between a “best of” and a “greatest hits.” “Make Believe” is more of the former and illustrates how far LaChapelle has come, but also in many ways, how he’s remained unchanged.

The show is only a few blocks from 303 Gallery, where LaChapelle had his first shows in 1984. “Angels, Saints, and Martyrs” depicted his East Village cohort posing in dramatic religious tableaux. At the heart of these works was a profound daily meditation of mortality.

“My friends were dying of AIDS so fast, I thought I was dying, too,” Lachapelle said. One of those early black and white works is on display, a triptych warmly printed with a saturated Man Ray metallic sheen. A female nude reaches for divine light. “She’s wearing a wig because everyone had short spiky hair,” LaChapelle said.

Behold (2015, Hawaii). Photo: © David LaChapelle, courtesy of Fotografiska New York.

As the press tour continued, we came across a recent image of a Christ-like figure in the woods. LaChapelle explained that the model is a dancer who is currently going through hardships, and then described how he makes the halo effect by using revolving LED lights and slow exposure.

A devout Catholic, LaChapelle frequently references Christ and during the tour he was dressed like a hip prophet, in nerdy black spectacles, orange Nike dunks and a shirt, hand-painted by his friend, the artist Stefan Meier, that was adorned with images of flaming doves, flowers, and hands with eyes. The words “Rain Stars Ultra Super Universe” were printed across the back.

LaChapelle revealed that he is again staging Bible-inspired scenes from his home base in Hawaii. He decamped there in 2006, escaping his gilded cage of celebrity success and excess in New York—and started cranking out a lot of work that critiques his former milieu.

Aristocracy: Private Pirates (2014, Los Angeles). Photo: © David LaChapelle, courtesy of Fotografiska New York.

A standout in the show are the still-life images from 2011’s “Earth Laughs in Flowers” series. Heady and romantic, LaChapelle was clearly inspired by Dutch masters and the photos look like oil paintings. But beauty camouflages decay. If you look closely, the sickeningly sumptuous blooms are beginning to wilt. Some are surrounded by cellophane, discarded cell phones, abandoned drugstore teddy bears, and other detritus.

“Vanitas traditionally are about the brevity of life,” LaChapelle said. “This one is kind of like our world today. Shopping online or for sex on apps—it’s like people shopping for body parts.”

Also of note is 2006’s darkly clever “Recollections in America” series, in which he sourced random vintage snapshots from eBay, inserted other characters and altered the final images. Another eye-catching series from 2014 featured private planes haphazardly flung about and floating in surreal, gradient airspace.

Earth Laughs in Flowers: Wilting Gossip (2008–11, Los Angeles). Photo: © David LaChapelle, courtesy of Fotografiska New York.

And although many of the photographer’s usual celebrity subjects are absent, transgender nightlife icon and forever LaChapelle muse Amanda Lepore looms large. In one image, she snorts a line of diamonds through a cocaine straw (the artist mentioned that this was a statement on materialism). Elsewhere she poses as a garish fever dream of Andy Warhol’s Marilyn and Liz.

A shot of her breast-feeding in a hooded faux sable coat is perhaps the most poignant. “Everything in this photo is fake,” LaChapelle said. “The fur, the baby, everything. But Amanda’s tears are real.”

Towards the end of the tour, LaChapelle got emotional as we reached an image of Travis Scott’s Astroworld album art, and the ensuing concert tragedy last November, when 10 people died being crushed in the crowd.

“They had taken my gold heads and painted them into skulls without permission, without asking,” LaChapelle said of the festival’s decorations, which he helped design. “The love of money is the root of all evil… all of that greed. That’s what killed those kids. And [then] they had to walk through a skull and see all this dark imagery. If imagery doesn’t matter, then why bother doing it at all? If art doesn’t have impact then why bother with it at all?”

After the preview, we briefly sat down with the artist at the gallery’s Veronika restaurant to discuss the show and his work over the years.

Fly On My Sweet Angel Fly on to the Sky (1988, Farmington, Connecticut). Photo: © David LaChapelle, courtesy of Fotografiska New York.

The celebrity aspect of the show was pretty low-key. When people think of you, they often think of images like Eminem holding a stick of dynamite.

That’s why its on the wall of the restaurant! It was a part of my life for a long time. I had that book called Lost and Found. There was a bit of getting lost after finding out that I didn’t have HIV around 1994. It coincided with suddenly getting contracts with Conde Nast Traveler, Vanity Fair, and Details.

I threw myself into that world, became a workaholic, and got lost. I really felt it was time to stop. And when I was young, I prayed for a cabin in the woods inside my little squat on 3rd Street. I’ve got that now.

It’s funny that your “wandering in the desert” period consisted of fortune and fame. You chose to leave fashion behind.

I was questioning this idea of happiness coming with the next purchase. I knew it wasn’t true, yet I was working in a world where that was the promise. That was a paradox.

Listen to Her (1986, New York). Photo: © David LaChapelle, courtesy of Fotografiska New York.

So much about your work is showing different versions and definitions of beauty. I was surprised that at the root of so much of your work was a rumination of death.

I don’t fear death, but I have been aware of it for a long time. I feared it a lot when I was a kid. My first boyfriend died of AIDS when I was 21. I didn’t go to a doctor for 15 years. Then, I had experiences that really lead me to believe that there is life after death.

I know that there’s something more than the material plane. I’m not afraid of death anymore. I want to live—as best I can and do the best pictures I can, because art does mean something. Images do mean something. And this was what I knew I was gonna do since I was a little kid. I was gonna be an artist.

I didn’t know I was gonna be a photographer, but I knew I was gonna be an artist. That’s been a calling, and I want to make pictures that mean something, not just look good.

“Make Believe” is now on view at Fotografiska New York, 281 Park Avenue South. Admission is $20-$30. Monday to Sunday, 9 a.m.–9 p.m.