Artists

Ian Felice’s ‘New England Gothic’ Visions Have the Art World Abuzz

Jonathan Anderson, Gabriela Hearst, and Josh Brolin are just a few of Felice’s celebrity fans. This week, his solo show opened at Half Gallery, New York.

Artist Ian Felice paints a world most often revealed in poetry. The painter and musician, who is best known as the singer-songwriter of the folk-rock band The Felice Brothers, lives in a small town in the Catskill Mountains, a few hours north of New York City, with his wife and two kids. There, he paints in a one-room 1873 wooden church which he has converted into his studio.

The church, with its storied and spiritual history, seems a fitting place for Felice’s phantasmagorical visions to surface, a painted world where animals and people converse in mesmeric interludes, where the conscious and the subconscious bleed together. A quietude, of folkloric sensitivity to nature, is part of their genesis.

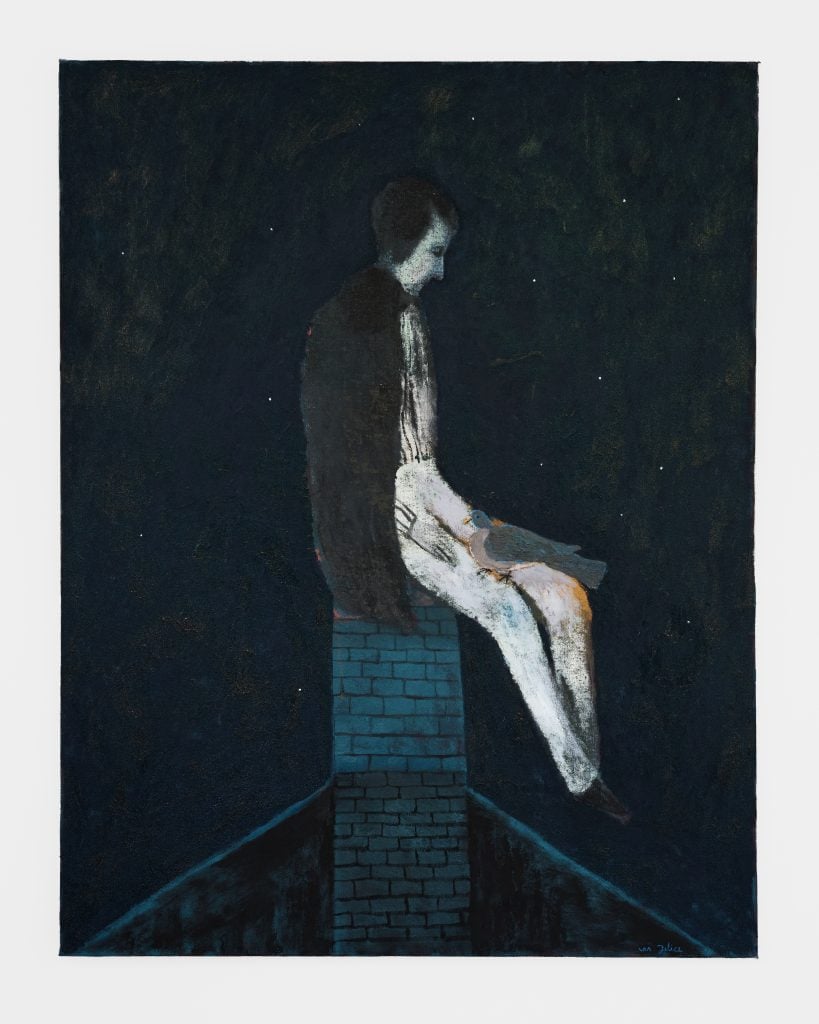

Ian Felice, Where Is Last Year’s Snow (2024). Courtesy of the artist and Half Gallery.

“My studio is surrounded by farmland and forest. I grew up in a very rural mountain town in the Catskills,” Felice (b. 1982) shared during a recent conversation, “As a kid, I lived on a dead-end road surrounded by forest. That’s the environment that puts me at ease and allows me to concentrate on work.”

When he’s not on the road with his band, the painter spends quiet days in the studio. This week, just after The Felice Brothers wrapped up their 2024 U.K. and European tour, the painter opened his second solo exhibition with Half Gallery, “To find me, follow the pigeons” which featured 12 new paintings made over the past year (the show is on view through December 21). This New York exhibition is a follow-up to his 2023 debut, “If the Hoarfrost Could Speak” which was presented at Half Gallery’s annex space.

Bill Powers, the gallery’s founder, discovered Felice’s work in a roundabout way. Jonathan Anderson, the creative director of Loewe, posted one of Felice’s paintings that he’s recently acquired on his Instagram account. Intrigued by the work, Powers set up a studio visit. The rest fell quickly into place.

Ian Felice’s studio in the Catskills. Photo: Ryan Guinn. Courtesy of the artist.

“Ian Felice’s work gives me the unique sense of nostalgia for a place I’ve never been,” said Erin Goldberger, director at Half Gallery who has worked closely with Felice on his current exhibition. “It is an embodiment of what Jean-Paul Sartre expressed in The Imaginary… ‘What is manifested through such works of art is an irreal ensemble of new things, of objects that I have never seen nor will ever see… objects that do not exist in the painting, nor anywhere in the world, but that are manifested through the canvas and that have seized it by a kind of possession.’”

Possession is an apt word for describing Felice’s work. Hauntology—a concept that the present is haunted by the experiences of the past—came to mind more than once while considering his works. After all, Felice’s paintings exist in an uncertain, perhaps unfathomable time; often figures appear attired in garments from a vague past. In one painting, Where Is Last Year’s Snow, a man in coattails sits atop a chimney in a night sky, a pigeon in his lap, with the night sky surrounding them both.

Ian Felice, The Nightwatch (2024). Courtesy of the artist and Half Gallery.

“In a lot of the paintings there’s an uneasy tension between darkness and light,” Felice explained. The painter is deeply informed by poetry, and William Blake’s “Auguries of Innocence” was on his mind as he painted his newest series; the poem is regarded as the first in the Western world to speak to ecological justice.

“Like most of Blake’s work, it confronts the two contrary states of human life, namely innocence and its destruction by the onward journey into experience,” Felice explained. “In the poem, Blake draws a prophetic connection between environmental degradation and social or moral degradation. There’s a darkness to the poem and a critique of society and religion and structures of power, paradoxically the poem acts as an ode to the beauty of the natural world. This sort of balancing act gives the poem its power.” Many of the paintings in the exhibition include imagery that can be found in the poem, from doves and pigeons to lions and wolves.

Connections between animals and humans feel haunting and even tender. “I’ve only had one recurring dream in my life and it goes like this: I’m going about my day and suddenly remember that there is some type of animal that I’ve been trusted to care for and have completely forgotten. I rush home in horror to find them starving or sometimes dead. At that point I wake up very disturbed,” he shared. “I’ve never been to a psychoanalyst but I think the dream comes from an anxiety about the state of the natural world.”

Such imagery is deeply rooted in the world of fairytales. The mythic sensibilities of these paintings have earned the attention of celebrity collectors including Josh Brolin, Rebecca Hall, and Morgan Spector. Designer Gabriela Hearst is a supporter of Felice as well, and he often wears her suits when he performs. (Felice’s paintings are priced from $4,000 to $15,000 for his show). These collectors seem drawn to the strange quietness of his paintings, where moments are left gestural, obscure, rather than any glitziness (Felice, for one, is a thoughtful, introspective conversationalist).

Photo Credit: Rose Felice.

“Ian’s paintings have a dream logic that exists where a kind of sinister madness and childlike imagination overlap,” Morgan Spector shared in an email. “They feel to me like translations of poems that can’t be rendered as language. He reminds me of Blake, and Poe and Edward Gorey, of a deeply American, deeply New England gothic.”

Felice, who attended art school before his music career kicked off, only returned to painting in earnest during the homebound year of 2020. Spector’s observations are astute; Felice’s painterly inspirations are bound deeply in poetry as well as American artists such as Henry Darger, Joseph Cornell, Frank Walter, Albert York, Albert Pinkham Rider, and Marsden Hartley. “There’s a sense of urgency in the artists that you mentioned,” Felice considered of the artists I brought to mind, “It’s as if their paintings had to come into being, regardless of the technical ability of the artist. There’s also a privacy about the work which gives it intimacy.” American Outsider artist Grandma Moses is also a potent source of inspiration. “I’m a child of Grandma Moses,” he added. “I’m in awe of the transportive power of her paintings…The thing I’m drawn to is the strangeness of the hand, the character that is imparted to the canvas, the imperfections and deformities of heart and mind.”

Ian Felice, The Theatre of the Thereafter (2024). Courtesy of the artist and Half Gallery.

A transportive power lives in these paintings too. In many of his paintings, there is a striking horizontal delineation between horizon and ground. In his painting The Theatre of the Thereafter, for instance, the painting depicts a theater with an audience below and a stage with giant poppies and a skeleton above. Other times, the division is the green ground and the night sky. This recurrent compositional bifurcation brings calls to mind the ancient Hermetic quotation “As above, so below,” the tensions between the terrestrial and celestial, our conscious and subconscious selves. “The most fundamental way to represent space is to make a horizon line that essentially splits the painting into two planes, whether its earth and sky, water and sky, the physical and spiritual, consciousness and subconscious, or any other contrary forces,” Felice considered. These realms are born from the pressures and forces that shape our internal worlds and our relationship to nature. “Painting is a a kind of dreaming or at least a kind of thinking that’s at variance with reality,” he said, “There are very few rules in the world of dreaming, that’s where I want my paintings to exist.”