On View

Figuration Is the Art of Our Era for a Simple Reason: Because Artists Are Painting ‘What They Love’

A new show at the ICA in Boston brings together eight young artists who are making new inroads into the dominant genre of today.

A new show at the ICA in Boston brings together eight young artists who are making new inroads into the dominant genre of today.

Taylor Dafoe

In art history, some decades are defined by a singlular style. In the ‘50s, it was Abstract Expressionism; the 60s, Minimalism; the 70s, Conceptualism.

Now?

“When we look back at this period of the 2010s, we’ll see that this was a moment of figuration,” Ruth Erickson, the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) curator behind a new exhibition dedicated to eight of the genre’s brightest young exemplars, painters Aubrey Levinthal, Arcmanoro Niles, and Celeste Rapone among them.

On Erickson’s point, it would be hard to disagree. In recent years, artists have reanimated the form with eyes sensitized to art history’s propensity for omitting marginalized communities and recapitulating a colonial gaze.

They’ve done so with tremendous success, filling galleries and museums—and auction lots and magazine covers—at dizzying rates. The demand has transformed these artists into merchandisable superstars, and their work into collector-bate—so much so, that discussions about the quality of their output are often discolored with the sickly greenish hue of money.

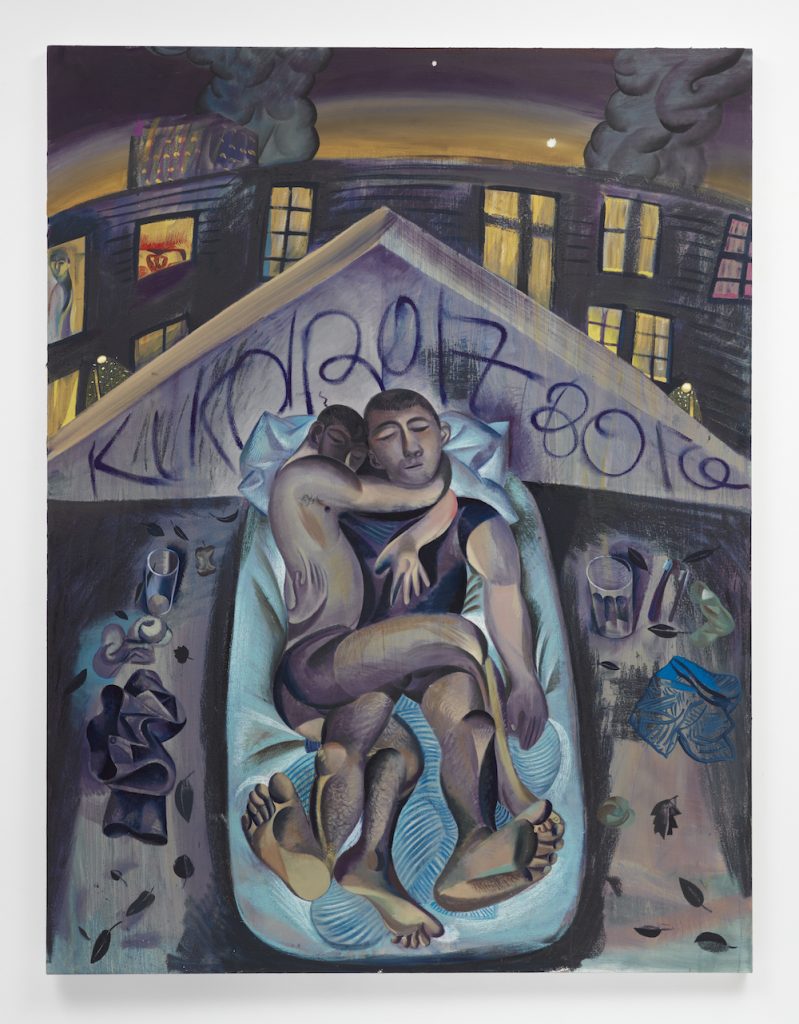

Louis Fratino, Sleeping on your roof in August (2020). Courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York. © Louis Fratino.

Erickson had no intention of letting the market enter the chat for her exhibition in Boston, called “A Place for Me: Figurative Painting.” To her, the show’s prompt wasn’t framed around a question of why people are buying this kind of art, but something slightly different: Why is portraiture so prominent right now?

“I think each of these artists has a different way of answering that question,” Erickson said. The show, she said, is “really about resisting that sense of trying to clump them together and instead trying to highlight them as eight individual voices with a shared interest in a type of art.”

(Still, the market created some obstacles: in several instances, pieces the curator had earmarked for the exhibition were snatched up by collectors.)

Erickson organized the show one artist at a time, selecting one based on another, occasionally asking chosen artists who they thought should be included.

From that process emerged a group of relatively young, emerging talents, rather than established stars, their respective approaches to figuration as varied as their backgrounds.

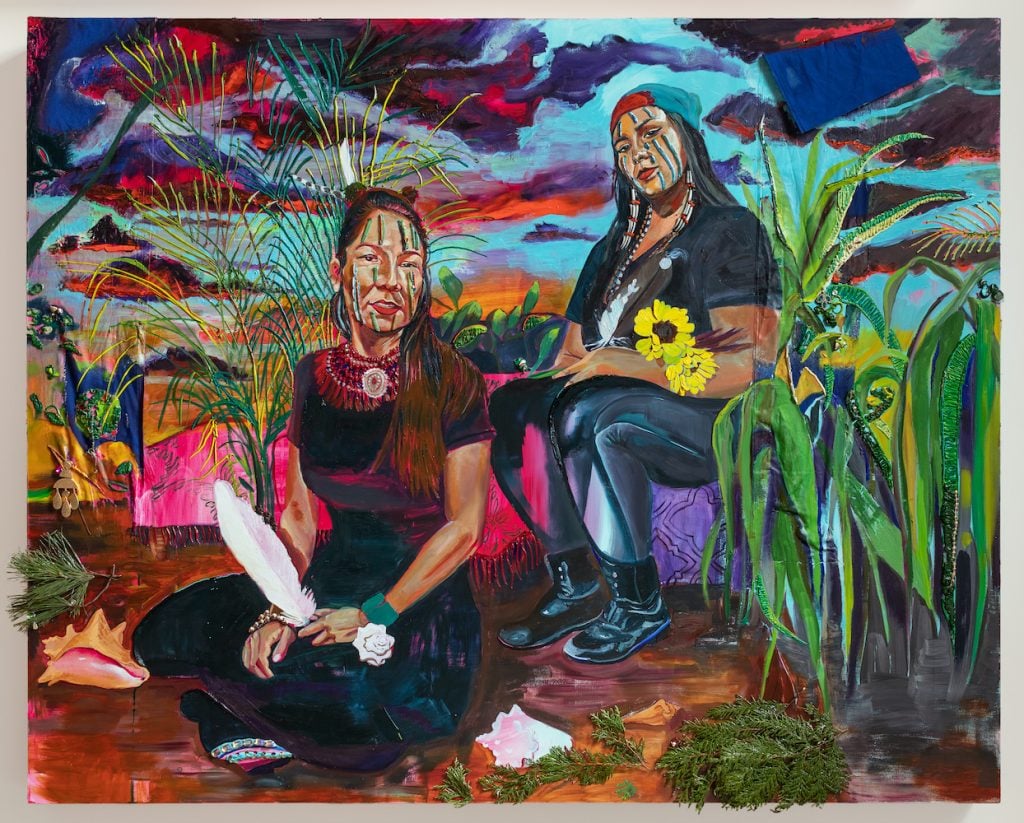

Gisela McDaniel, Created for Such a Time as This (2020). Courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corrias, London. Photo: Clare Gatto. © Gisela McDaniel.

Only one artist, David Antonio Cruz, was alive before the ‘80s. (He was born in 1974.) Viewers will find in his staged portraits of Black, brown, and queer sitters the show’s most “realistic” approach to figuration, though that’s not to say the artworks don’t leave room for interpretation.

The artist’s two diptychs in the show each feature overlapping imagery and gaps between the canvases—an acknowledgment, Erickson pointed out, of painting’s inability to truly communicate the human experience.

The exhibition’s youngest artist, Gisela McDaniel (born in 1995), similarly points to what’s beyond her canvases. While painting portraits of women and non-binary people of color who have experienced personal or inherited traumas, the artist invites her sitters to record audio statements about their stories.

“Many of the people in the paintings have difficult but important stories that other people need to hear. They’ve been erased historically,” McDaniel told Artnet News earlier this year. “With every single person, I ask for permission every step of the way, especially when I’m painting somebody. I can’t expect that back, but I hope when people experience my work, they walk away from it with a kind of awareness to move around people with respect. That’s a big reason I incorporate voice.”

Doron Langberg,Sleeping 1 (2020). Courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery, New York, and Victoria Miro, London. © Doron Langberg.

Elsewhere in the ICA show are Louis Fratino’s (born in 1993) quotidian still lifes and moments of tender queer love, each enlivened with a kind of Cezannian perspectival play. Another artist, Doron Langberg (born in 1985), is drawn to similar scenes, but he finds sensuality through a softer, more Impressionist approach, with details that come in and out of focus like the first moment you crack open an eye in the morning.

In organizing “A Place for Me,” Erickson asked many of the participating artists why they painted figuratively. “The resounding answer,” she explained, “was because they paint what they love. It was so simple.”

“I think it comes from this moment of empathy and humanism and softness that we’re at, where the blinders have been pulled back,” Erickson added. “We know that we should be spending time on the stuff that we love the most.”

“A Place for Me: Figurative Painting” is on view now through September 5, 2022 at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston.