People

Dealer Monya Rowe on the ‘Naivete and Chutzpah’ That Has Made Her New York Gallery a Standout for 20 Years

The gallery first opened in a former bakery building in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, in 2003.

The gallery first opened in a former bakery building in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, in 2003.

Katie White

Gallerist and dealer Monya Rowe knows that nothing is promised—at least in the New York art world. Fluctuating tastes and trends, sky-high rents, and market bubbles and bursts are the simple facts of life in the city’s gallery world. Over the years, Rowe has faced them all, coming away with some lessons and even more tenacity.

This year Monya Rowe Gallery, which has built its reputation on an unexpected group of mostly women artists, is marking its 20th anniversary—and is still building on its successes. Just last month, the gallery moved into a new, expanded space in the same 30th Street building in which it has been located since 2018.

“The new space is on a different floor and is about three times larger,” Rowe said. “I wanted the artists I work with to have a little more freedom to exhibit larger works and to show more in each exhibition.”

Cindy Bernhard, Stairway (2023). Courtesy of Monya Rowe Gallery.

“Holy Smokes,” an exhibition of works by artist Cindy Bernhard, inaugurated in the new venue. Bernhard’s iridescent, nocturnal paintings have something aptly ceremonial about them—the saucer-eyed cats with shiny, thick coats that haunt these canvases are accompanied by luminous mirrors seemingly plucked from fairy tales, as well as glowing candles, that are seemingly metamorphic in their melting forms. One could imagine the show as a kind of ritual mass, blessing the space.

The uncanny exhibition is befitting of Rowe, whose keen eye has been her guiding ethos. This week, the gallery will open “Duality: The Real and the Perceived“, a summer group show that brings together a crop of works by gallery artists, including Anastasiya Tarasenko, Aubrey Levinthal, Larissa Bates, and Bryan Rogers, as well as artists with longstanding relationships with Rowe, and a few who are new acquaintances.

Rowe is a rare bird in the world of dealers, as one of just a few women gallerists whose spaces in New York have endured over the decades. Add to this the fact that Rowe has focused primarily on women artists and the pool gets even smaller. And that she is entirely self-funded puts her among a handful of her peers.

“I’ve always navigated toward figurative art and that didn’t change even when it seemed like everyone was showing abstraction,” Rowe said, of her gallery roster. “The roster does lean more heavily toward women, even since the beginning, but it’s not deliberate. I choose work that I think is good and significant, not based on gender. Maybe one day things will be reversed and people will ask a gallery why they show mostly men. We’re not there yet.”

A street view of Monya Rowe Gallery’s now-demolished original Williamsburg location.

So, how has she managed to stay in business? Rowe credits a kind of blind tenacity with the gallery’s formation and success. The Australia-born dealer got a later start in the art world, only entering the sphere professionally in her 30s. “I was getting depressed working at meaningless jobs I didn’t care about and knew I had to figure out a job I could do that I didn’t hate going to each day,” Rowe recalled, “I was always into art and I really just somehow decided that I was going to be a dealer. In retrospect, it was kind of nuts because I had no money and no connections, but I had a big enough ego to think I should be the one making the decisions combined with a lot of naivete and chutzpah.”

The early days of her career were neither glorious nor glamorous. After finding work as a gallery assistant, Rowe ultimately opened her own space in the southside of Williamsburg in 2003. “The first space was in an old bakery building that was turning into artists’ studios. I asked the owner if I could have a gallery there,” Rowe said. “It was $500 per month and freezing. I installed a buzzer on the building entrance and had to physically get up and let people in each time. I remember someone was shooting up heroin on the front steps one time.” The building has since been torn down and turned into luxury condos, Rowe recalled.

Aubrey Levinthal, Coffee Shop (Barista) (2022). Courtesy of Monya Rowe Gallery.

Meanwhile, the fledgling dealer tried to build her reputation by curating exhibitions in spaces throughout the city. “The second show I curated was at White Columns which Ken Johnson of the New York Times wrote about it in 2003,” she recalled.

Rowe quit her gallery assistant job soon after opening her space and took a 9-to-5 job outside the art world. “I wanted to be seen as a dealer, not a gallery assistant,” she explained, “I worked 7 days a week for about a year. 5 days at my day job and the weekends at the gallery. During this era, galleries were open in Williamsburg on weekends, so people would go to Chelsea during the week and Williamsburg on the weekends.”

Monya Rowe Gallery’s first exhibition—a group show of works on paper—earned a review from Roberta Smith who called the space “possibly the smallest white cube in the New York art world.”

Polina Barskaya, Before Bed in London (2023). Courtesy of Monya Rowe Gallery.

Less than a year after opening, the gallery relocated to a space on 26th Street in Chelsea. Then, in 2013, the gallery relocated to Orchard Street on the Lower East Side, where it operated for two years. In 2015, the gallery racked up three consecutive reviews in the Times, but later that year, Rowe closed up shop in New York and relocated to St. Augustine, Florida.

The artist Angela Dufresne reflected upon the departure in an essay as a sign of the rocky road faced by self-made dealers operating outside the mainstream market. The exodus, however, was brief, and in 2018 Monya Rowe Gallery returned to New York, taking up residence in its current building in the Flower District, in a former fur storage and manufacturing factory.

Rowe is particularly beloved and respected by her artists, who urged her to come back. In her career, she has given first solo shows to artists including Dufresne, Josephine Halvorson, Vera Iliatova, Jacolby Satterwhite, and Devin Troy Strother. “It’s important that the work is good, but also that I connect with the artist on a human level and that we both respect and value each other. It is a marriage in some ways,” she said. “I naturally beat to the tune of my own drum, so I guess that’s how I run the gallery.”

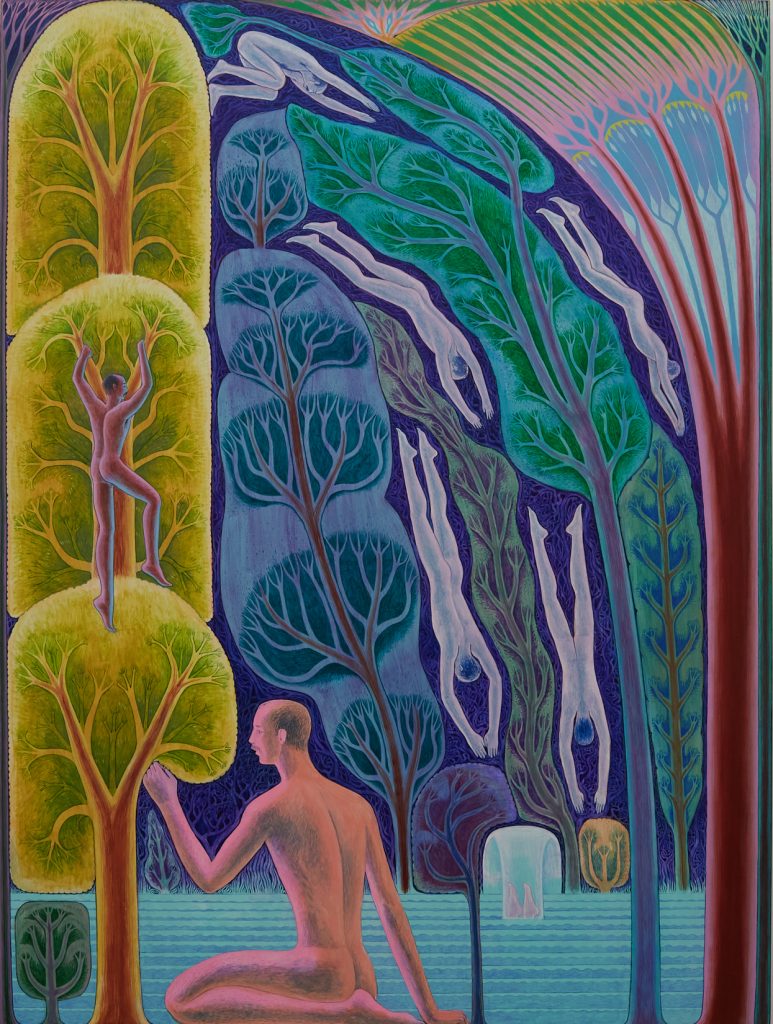

Bryan Rogers, Diving Right (2023). Courtesy of Monya Rowe Gallery.

Her collector base perhaps unsurprisingly cuts a wide swath, ranging from big names to first-time collectors. “Some gallery visitors have never bought work or even thought about it, but leave owning a work. That’s always exciting as it sort of demystifies that members-only facade galleries give off,” she said.

Rowe credits the gallery’s endurance to a community of artists, collectors, fellow gallerists, writers, and art-loving visitors to the gallery that have kept things inspired. She also chooses to focus inward rather than looking outward. “I make decisions based upon what’s right for me and the artists not what the trends are or what everyone else is doing,” she noted. “I also think that is generally just a healthy way to live. The art world has a way of infiltrating one’s psyche in a negative way. It’s easy to start comparing yourself to others, and that is never a good thing to do.”

More Trending Stories:

Is Time Travel Real? Here Are 6 Tantalizing Pieces of Evidence From Art History