Art World

What Is the Most Iconic Artwork of the 21st Century? 14 Art Experts Weigh In

How do you choose one defining artwork for a century still in its adolescence? Some of the art world's leading figures take their best shot.

How do you choose one defining artwork for a century still in its adolescence? Some of the art world's leading figures take their best shot.

Artnet News

Want to make an art historian laugh? Ask them to name the most iconic artwork of the 21st century. Turns out, it’s not so easy to single out the most significant work of art created over the past 17 years. Nevertheless, some leading figures in the art world—from curators and gallery directors to artists and auction house executives—gamely agreed to try their hand at narrowing it down.

What single artwork defines this awkward, information-addled teenage century? Some simply couldn’t choose just one work, while others ultimately refused to answer at all. But many, to our pleasant surprise, told us exactly what they think. Below, 14 art experts weigh in on the 21st century’s most iconic artwork.

Pablo Helguera, The School of Pan-American Unrest, 2006. Installation view, Schoolhouse in front of the Galeria Nacional de Arte, Honduras. Courtesy of the Artist

Pablo Helguera’s The School of Panamerican Unrest (2005). A multi-months-long performance that unfolded between Alaska and Argentina, The School of Panamerican Unrest saw artist Pablo Helguera drive through the Americas with a portable schoolhouse and lecture podium as he conducted think tanks, lectures, and artist statements throughout North, Central, and South America. It stands, for me, as one of the most important durational artworks of this century, and its message of unity, dialogue, and collaboration is more important now than ever before.

Kara Walker’s A Subtlety (2014). Monumental in its scale and critical in its necessity and timeliness, Walker’s 2014 sculpture—made for an installation at a former Domino Sugar factory in Brooklyn—stands as not only one of the greatest works of the 21st century but perhaps of all time. Its forceful presence empowers women, subaltern voices, and anyone who stands for social justice and equality, just as it stands as one of the strongest messages ever made against the ongoing legacy of slavery and racism in this nation, and by extension, the world.

Teshima Art Museum by Ryue Nishizawa and Rei Naito (2010). Decisively the perfect installation seamlessly combining Nishizawa’s architectural triumph and Naito’s pure magic, the project becomes an otherworldly realm that transports viewers into a zone of meditation and awe that ultimately takes one’s breath away. Naito’s subtle, yet highly engineered addition of water droplets that become animated—seemingly alive organisms to Nishizawa’s sleek space—makes the viewer stop in her tracks, endlessly puzzled by how the action before her occurs.

Marta Minujín, The Parthenon of Books (2017), Friedrichsplatz, Kassel, documenta 14, Photo: Roman März.

Marta Minujín’s The Parthenon of Forbidden Books. An icon of her time, the Argentinian artist was invited to participate in documenta’s last edition with her Parthenon of prohibited books, which was originally constructed in Argentina after the country’s military dictatorship fell in 1983 to celebrate the recovery of democracy and to protest against censorship. Thirty-four years later, the piece returns to propose a massive collaboration re-evaluating and reinforcing freedom in a different context. (She is also an absolute pioneer of art.)

Anne Imhof’s Faust installation from the German Pavilion was awarded the Golden Lion for Best National Participation at the Venice Biennale. It is a powerful and disturbing performance installation that poses questions about the present and the contemporary society. The young German artist achieves with Faust a provocative piece of challenging beauty. An experience that bothers, and becomes extremely irresistible—an absolutely contemporary experience.

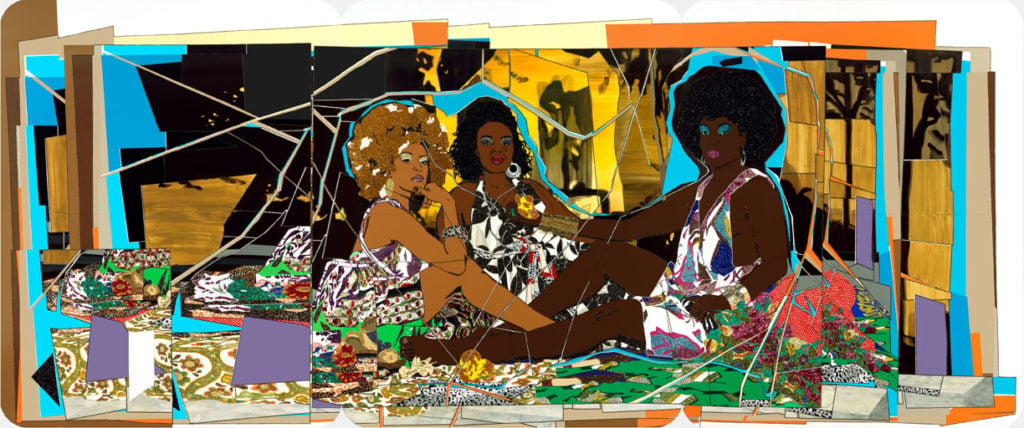

Mickalene Thomas’s Le Déjeuner sur L’herbe: Les Trois Femmes Noir (2009). Image courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin Gallery.

Mickalene Thomas’s Le Déjeuner sur L’herbe: Les Trois Femmes Noir (2009). Subverting a mostly white and male art history, Thomas shows us the way forward. Using nontraditional, craft media, she mixes high and low—taking the once scandalous Manet painting and turning it into a tête-a-tête of glamorous black women, exploring beauty, race, and constructed identity. This was also a site-specific wall piece in the windows outside of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Cassils, PISSED (2017). Image courtesy of the artists and Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York

Cassils’s PISSED (2017). PISSED consists of a glass cube containing 200 gallons of urine. A collection of all the liquid the artist has passed since the Trump administration rescinded an Obama-era executive order allowing transgender students to use the bathroom matching their chosen gender identities. The sculpture is contextualized by audio recordings from the Virginia school board and the Fourth Court of Appeals articulating the ignorance and biases that run through every level of judicial proceedings.

Pussy Riot’s Performance at Cathedral of Christ the Savior (2012). The video documents a performance to denounce the support of Putin’s re-election by the Orthodox Church. The video and the subsequent trial and sentence brought international attention to the state of free speech in Russia.

Marta Minujín’s Parthenon of Books (2017). Over 100,000 formerly or currently banned books from all over the world materialized a replica of the temple in the Acropolis in Athens—the cradle of democracy. The installation took place at Friedrichsplatz in Kassel, where, on May 19, 1933, some 2,000 books were burned by the Nazis. At the end of the exhibition, visitors can take books home with them. This installation traces its origins to a similar work created in Argentina in 1983, shortly after the collapse of the civilian-military dictatorship there.

James Turrell’s Roden Crater (ongoing). ©2017 Skystone Foundation, © James Turrell.

James Turrell’s Roden Crater. Still in progress, it’s the work of a lifetime. Many artists tried to work with light but none could reach James Turrell’s level.

Kara Walker’s A Subtlety…or the Marvelous Sugar Baby (2014). Image courtesy of gigi via flickr.

It’s important to think about how we define “best” and how we define “work of art” now. I think of cultural relevance, of artworks that probe issues in contemporary society, so my choice would be Kara Walker’s “A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby” (2014) at the Domino Sugar Refinery in Brooklyn. Not only was it a very finely crafted, brilliantly engineered work of art that reflected the past, present, and future of our world, that created stories, but it also was completely integral to an architectural space, which it brought back to life. And it was a complete sensory experience: It was sticky on the walls, so there was a sense of touch, and one of my favorite things about it, too, was the smell of the sugar.

But here at the Met, my world is the whole world, so I’m also thinking of the works we’ve lost, in Palmyra, in Syria, in Mosul, and in Nimrud, as well as Confederate statues. In a historic sense, culture and heritage, identity and humanity are intertwined, so the work that now exists is in our memory. Videos of the destruction are perhaps news, not art, but they do become performative in the way they make us think about culture.

Ai Weiwei alongside his work Straight (2015). Photo by Alex B. Huckle/Getty Images.

Works like Olafur Eliasson’s golden sun in The Weather Project, which filled the Turbine Hall at the Tate in 2003; and Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s The Floating Piers (2014–2016) come to mind. These were ambitious and memorable artworks that reveal the potential of contemporary art to engage not just art lovers, but anyone and everyone, and for that, they’re very beautiful.

But I’d have to say my choice is Ai Weiwei’s Straight from 2008–2012. It is impressive in scale and beauty, but even more in what it has to say. Made of 150 tons of steel rods from buildings damaged in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, it’s a profound and beautiful memorial to the events and those that lost their lives. To make the work, the artist collected the twisted steel rods, and then—with his studio—hand bent them back into shape. It must have been an astonishing undertaking, and my feeling is that his work is some of the most genuine art being made today.

Janet Cardiff, The Forty Part Motet (2001) installation at Fuentiduena Chapel at The Cloisters museum and gardens. Image: The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Wilson Santiago.

Janet Cardiff’s The Forty Part Motet (2001). In 2017, we talk a lot about virtual and augmented reality. It’s maybe useful then to look back and celebrate an artwork that, from where I sit, prefigures and speaks to all of these things. Janet Cardiff’s work, in which 40 loudspeakers replay a multi-channel recording of a choir, one voice per speaker, performing an 11-minute work by the 16th-century English composer Thomas Tallis, is deceptively simple. What makes it magical, to me, is the way it completely transports the audience, putting us in the center of an absent choir whose voices are transformed by the acoustics of the installation space. I can think of no better VR experience than to close your eyes in the middle of the installation; I can think of no better AR experience than to walk from speaker to speaker and listen to the voices, one by one, and how they transform and are transformed by their surroundings.

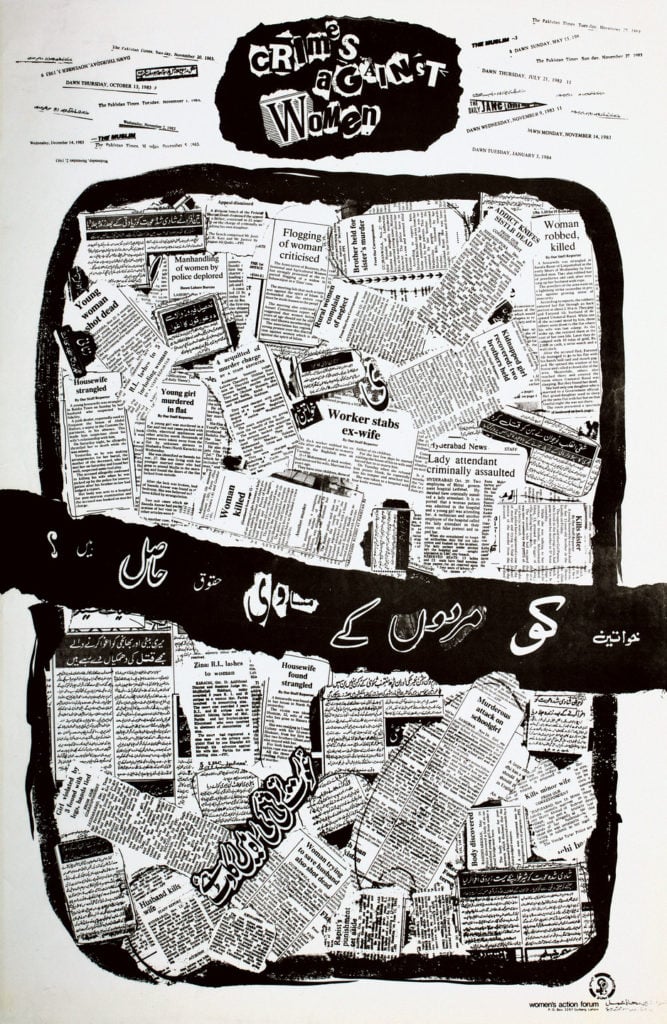

Lala Rukh, Crimes against Women (1985), poster for Women’s Action Forum campaign. Image courtesy documenta 14.

It’s difficult to single out a specific artwork, however Pakistani activist and abstractionist Lala Rukh has had a significant impact on contemporary South Asian art. A founding artist of Grey Noise gallery, her work was meditative and minimalist, and her recently commissioned work shown at documenta 14 in Athens, and a collection of historic works in Kassel, will now take on an even greater significance, as we sadly lost Lala earlier this summer.

Peter Zumthor’s Bruder Klaus Field Chapel (2007). Photo by Florian Seiffert, courtesy of Creative Commons.

Peter Zumthor’s Bruder Klaus Field Chapel (2007) in Mechernich, Germany. It is an exercise in symmetry, composure, and sensuality wrought from the material contrasts of concrete and burnt wood. It is a 21st-century observance of abstraction and profound humanism.

Damien Hirst’s For the Love of God (2007). Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2012.

Damien Hirst’s For the Love of God (2007) is my choice for the most iconic artwork of the 21st century. It represents the commodification of art and the nihilism of the early part of this century. I don’t believe it is a great work of art, but rather a manifestation of a particular culture—the art world—at a particular moment in time.

Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project (2003). Photo: Studio Olafur Eliasson

Courtesy the artist: neugerriemschneider, Berlin: and Tanya Bonakdar, New York

© Olafur Eliasson 2003.

Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project (2003) at Tate’s Turbine Hall. At the beginning of the new millennium, weather—particularly climate change—and the environment became a major global issue and a topic of discussion pervading all realms of discourse. This work was a synthesized landscape—a symbol of human-made or “artificial nature,” and for six months, it provided a situation in which people could interact with it like a natural phenomenon; they could lay back as though at the beach, sit in reflective meditation, or freely express themselves in its presence in whatever ways their sensibilities required.

Amar Kanwar’s The Sovereign Forest (2011–). Image courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery and the artist.

1. Amwar Kanwar’s The Sovereign Forest (2011–); 2. Nalini Malani’s Transgressions (2011); 3. Imran Qureshi’s Blessings upon the Land of my Love (2011); 4. Shilpa Gupta’s Untitled (2014) from the Dhaka Art Summit; 5. Naeem Mohaiemen’s Rankin Street (1953); 6. Bharti Kher’s The Skin Speaks a Language Not Its Own (2006); 7. Nilima Sheikh’s Each Night Put Kashmir in your Dreams (2003–2014); 8. Shahzia Sikander’s Parallax (2013); 9. Huma Bhabha’s The Orientalist (2007).

Kwan Sheung Chi’s ONE MILLION (Japanese Yen) (2012). Courtesy of Yuka Tsuruno Gallery, Tokyo, and Gallery Exit, Hong Kong.

Kwan Sheung Chi’s video, ONE MILLION (Japanese Yen) (2012); Samson Young’s “Songs for Disaster Relief” (2017) at the Venice Biennale; Tino Seghal’s performance, This Variation, at documenta 13 in 2012.

Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa (1503–1517). Courtesy of the Lourve, via Wikipedia Commons.

The most iconic work from 2001–2017? A misuse of the word icon for a period that is destined to fade into oblivion. There’s no Mona Lisa, Raft of the Medusa, or Guernica to be found here.