Museums & Institutions

Indigenous Groups Respond After U.S. Museums Cover Native Displays

Institutions including the Field Museum and American Museum of Natural History have covered their Native American displays.

Institutions including the Field Museum and American Museum of Natural History have covered their Native American displays.

Adam Schrader

After several U.S. museums closed displays of Indigenous objects last week, Native American groups are responding with support of the new regulations added to a federal law that require museums to receive consent to display certain cultural artifacts and human remains.

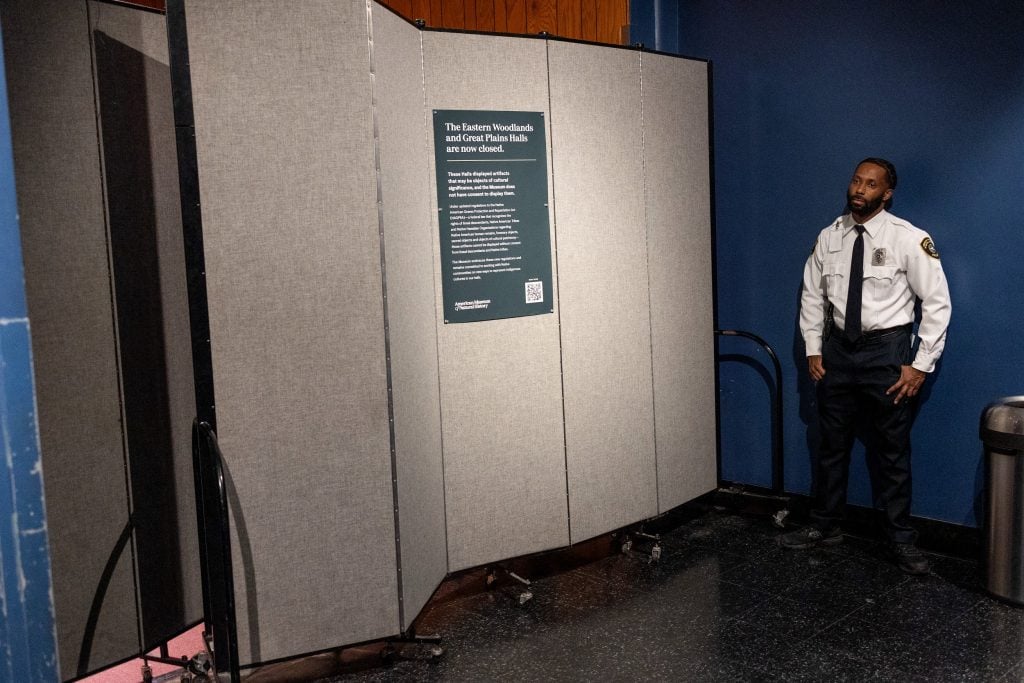

Museums, starting with the Field Museum in Chicago, began covering displays of such artifacts after new regulations went into effect January 12. The American Museum of Natural History in New York City, Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, and the Cleveland Museum of Art followed suit several days later.

Covering displays or taking things down isn’t the goal, according to Shannon O’Loughlin, head of the Association on American Indian Affairs. Rather, it’s part of a much larger repatriation process.

“The new regulations are crystal clear now: institutions do not own much of their Native collections and therefore, they must ask for consent from affiliated Nations before they can do anything with these items,” she told Artnet News. “When institutions actually have a conversation with affiliated Nations, they finally learn what they have in their collections.”

O’Loughlin added that the only exception to the repatriation of Native American artifacts under the law is if a museum or institution can prove they received consent when the item was taken.

The first day of the closure of the American Museum of Natural History Eastern Woodlands and Great Plains exhibition halls on January 27, 2024 in New York City. Photo by Andrew Lichtenstein / Corbis via Getty Images.

The regulations are additions to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), signed into law in 1990 by Republican President George H.W. Bush, and made by the U.S. Department of the Interior in December after a 90-day comment period with feedback from tribes and other groups. The law does not apply to the Smithsonian Institute’s National Museum of the American Indian, governed by its own National Museum of the American Indian Act.

The Native Governance Center, a nonprofit organization that seeks to boost the sovereignty of Native American nations, noted in a post on social media that NAGPRA was first passed more than three decades ago and that progress has been “incredibly slow” toward the restoration of about 96,000 human remains.

Nevertheless, “changes to the law this month have already created some real short-term changes across the U.S.,” the organization said.

Some museum professionals and academics have consistently voiced concerns that the new regulations will harm or limit research or censor scientific inquiry. Elizabeth Weiss, an anthropology professor at San Jose State University, authored a recent op-ed in the City Journal in which she claimed the regulations “depart completely” from the intent of the original law and may now violate the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

While the law has largely applied to natural history and ethnographic museums thus far, Weiss suggested that the latest NAGPRA regulations could be extended to art museums.

“New targets are sure to include art purchased from contemporary Native American artists,” she wrote, citing a recent NAGPRA information session about the new regulations in which museum curators were told to consult with tribes over the display of objects created by contemporary Native American artists that had been recently purchased for display. “This may lead to art museum curators deciding to avoid NAGPRA hassles by ceasing to buy or display the works of Native American artists.”

Weiss has been a vehement critic of returning human remains, and her social media posts on the topic ignited a controversy last year that has resulted in her voluntary resignation from the university in May 2024, after the academic year finishes.

Many supporters of NAGPRA say the cause for alarm sounded by critics like Weiss is unfounded and have pointed out that compliance with the new regulations doesn’t mean any museum’s exhibitions dedicated to Native Americans will remain closed forever. If museums obtain consent for the items in their collections, they are free to display them. For example, though not specifically operated by Native Americans, the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff has since made it explicitly clear that every item in its gallery was chosen by tribal delegates.

“MNA works closely with tribal consultants for items displayed throughout the museum,” the museum said on social media. “Visitors to MNA can feel comfortable knowing we comply with the updated NAGPRA regulations.”

“This is not a prohibition against research or exhibits—quite the opposite,” O’Loughlin says. “Just speak with any institution that has followed NAGPRA’s requirements and repatriated. They have built long-lasting relationships with those Native Nations and have developed strong exhibitions and research based on that consultation and collaboration, which includes the expertise and knowledge of Native Nations that science has ignored.”