Art & Exhibitions

How an Aluminum Mine in Jamaica Became the Conceptual Core of Breakout Artist Jamilah Sabur’s New Miami Show

We spoke with the artist on the occasion of her latest exhibition.

We spoke with the artist on the occasion of her latest exhibition.

Melissa Smith

Jamilah Sabur approaches her artistic practice the same way a mathematician solves an unproven theorem: through a slow, methodical “long exploration,” as she calls it, done over many years.

Since her time as an undergrad, “it feels like I’ve been working through the same thing,” Sabur says. “It’s like this one, continuous [line where] everything folds into itself.” And it will take her “50 or 60 years,” she guesses, to really make sense of what that thing is. So at the age of 34, the artist is only just getting started.

Given the depth of Sabur’s conceptual preoccupations, it is no surprise that she refuses to confine herself to one medium. She once said she has “an everything-but-the-kitchen-sink approach,” putting “every damn thing in there like a mind map.”

Early in her career—around the time she was working on an MFA degree at UC San Diego— she was dabbling in experimental filmmaking, but Sabur refuses to be hogtied to the genre. Two years after her debut solo show at Miami-based Nina Johnson Gallery, which featured a series of sculptural wall pieces, her latest exhibition there, “DADA Holdings,” focuses on paintings and should be considered in tandem with Bulk Pangaea, Sabur’s video installation in this year’s edition of Prospect New Orleans. Her work has also been included in “The Willfulness of Objects,” a group show featuring works by an all-star line-up of artists from the Bass Collection in Miami Beach.

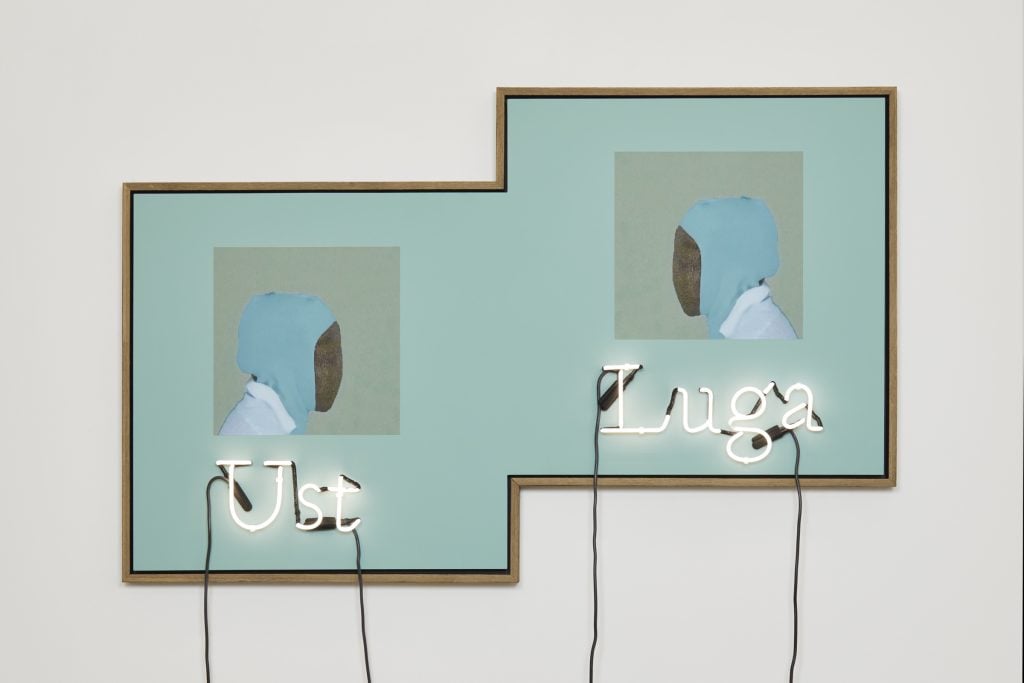

Jamilah Sabur, Ust Luga (2021).

Given the back-to-back culmination of these projects, Sabur admits to feeling a bit frazzled; she feels like she’s now “deep underwater.” The reference seems fitting given how strongly geology factors into her practice. Sabur often uses science as an entry point for examinations into the social, political, and climate conditions throughout history of any given place. And according to Sabur, her latest projects—the paintings and the video installation—are about “the relationship between colonial and postcolonial extraction.”

For her installation at Prospect, Sabur, who was born in Jamaica in 1987, started by asking herself, “Well, what is the geology of New Orleans?” That simple query set off a series of discoveries that tied New Orleans to Jamaica—and incorporated Belgium through the image of an escarpment (a cliff or steep slope), which the the Duke of Wellington once used to defeat Napoleon, just as escaped African slaves living in Jamaica had against the British almost a century early.

Sabur’s explorations started with the Michaud fault, a geological formation that runs underneath the eastern part of New Orleans. Through her research, Sabur then learned that NASA builds their rockets in a manufacturing facility located directly on the fault. And what are the rockets made from? Aluminum. Wondering where the aluminum came from, Sabur found out that it was partially supplied from Jamaica, where she lived until she was 4 years old.

Sabur then traveled to Jamaica to film the aluminum mine, the mountainous rainforest surrounding it—where enslaved workers once attempted to escape from British and Spanish colonizers—and the ship that exports the natural resource to Louisiana.

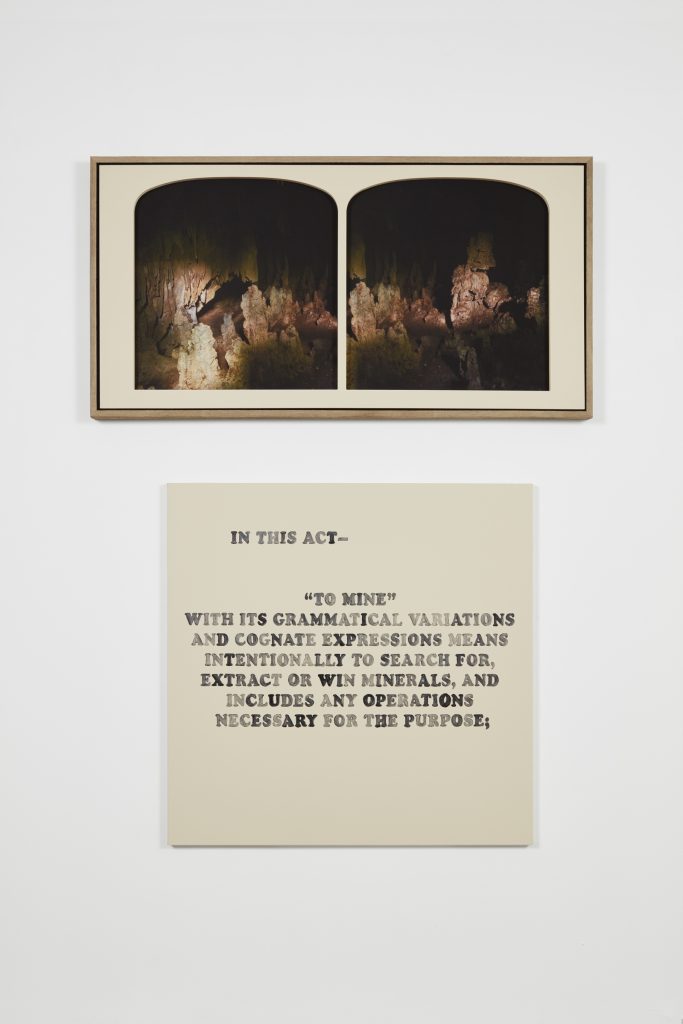

Jamilah Sabur, In this Act (2021).

Converting stills from Bulk Pangaea into stereoscopic images, Sabur’s paintings and text works in “DADA Holdings” are an “object-base[d] exploration,” she says, of the same themes. The works reference the Jamaican mining act of 1950, which cemented the island’s role as the major supplier of aluminum to North America. Continuing her deep dives into “networks of extraction across the planet,” she explained in an email, Sabur feels as though “the actual sites of extraction are just the shadows of what has already happened.”

To that end, this work is, for one, “a commentary on how this extraction of natural resources is very similar to the colonization of certain spaces, and her thinking about the impact of both extraction and colonization on indigenous people” Erin Christovale, the Hammer Museum curator who organized her first major solo museum presentation in 2019, told Artnet News.

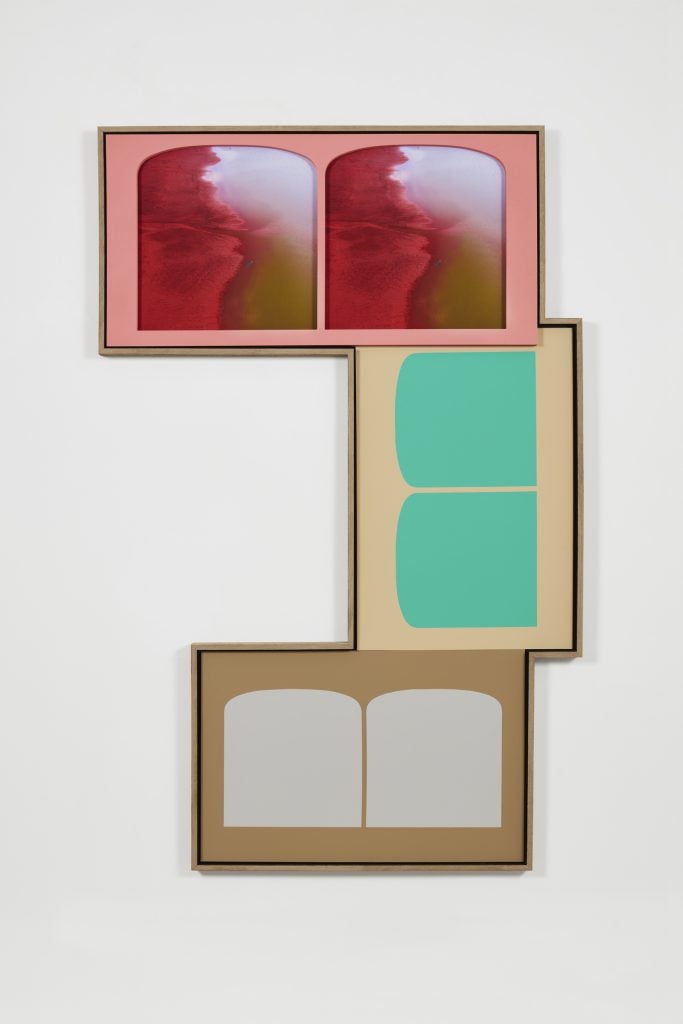

Jamilah Sabur, Black Forest, Bauxite, Black Sea (2021).

Sabur’s exhibition at the Hammer was her breakout moment. Familiar with her work since visiting her 2014 thesis show at UC San Diego, Christovale felt like Sabur’s films “always needed to branch out, to be multi-dimensional and function more as an installation or an environment.” So the curator let Sabur take over the Hammer’s project space with Un chemin escarpé (“a steep path”), an immersive, five-channel video installation.

The work is something that viewers “can really inhabit,” Sabur said, rather than simply just watch, and the videos mainly show landscape images, with no linear narrative or dialogue, only a score the artist herself composed. The installation is also a sort of precursor to Bulk Pangaea now on view at Prospect, mining “geographical spaces as a way to think through colonization, environmental justice, and the politics of immigration,” as Christovale noted in her announcement of the show on Instagram.

Prospect curator Diana Nawi has been following the evolution of Sabur’s practice for nearly a decade. Of late, she feels as though “Jamilah has landed on forms and ideas that I think can really carry her through her practice for a long time,” she said. “They’re timeless but also so relevant to our moment.”

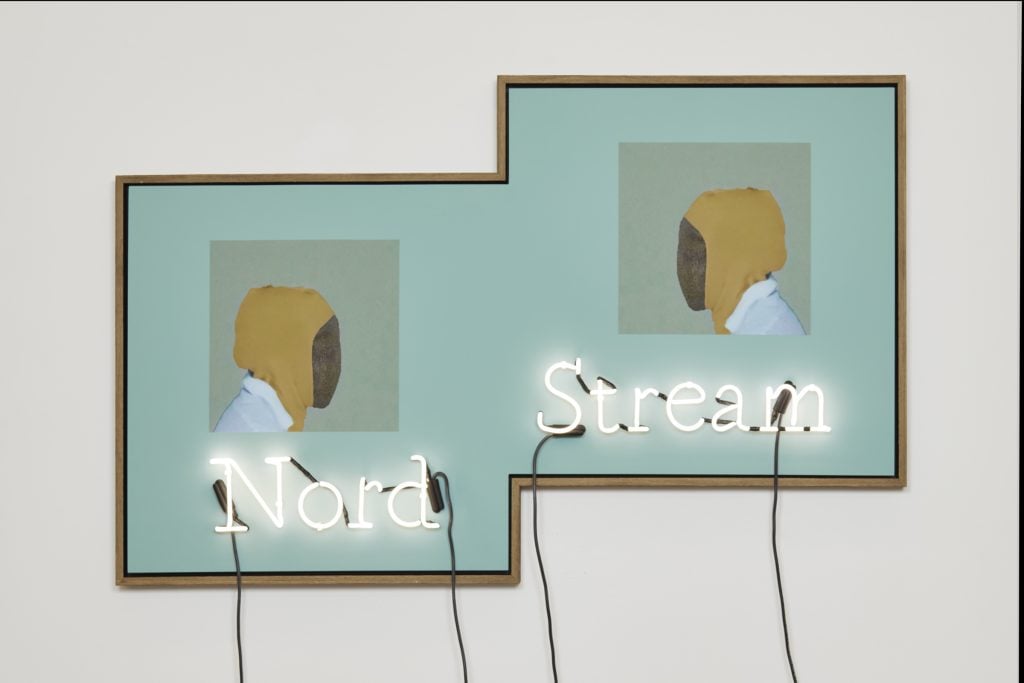

Jamilah Sabur, Nord Stream (2021).

In the last few years, her “ideas around place, science, geography, and geology have become more expansive within her practice,” she continued. “I think her Hammer Project and what she’s done for Prospect both really speak to that.”

Her piece for Prospect, in particular, is also deeply personal. Incorporating images of various Jamaican landscapes, along with the symbolic use of the rhomboid shape—a reference to the threshold of her mother’s old home on the island—Sabur not only leans into her history as a citizen living primarily outside of her home country, but also addresses the idea of feeling stuck between two places.

She also utilizes her background in performance, engaging in deliberate, ritualized movements in the videos, which give viewers the sense they’re not only inhabiting the installation space, but also crossing through a portal into Sabur’s innermost psyche.

What Christovale was immediately drawn to in Sabur’s videos was how they “really challenged what you assume of a Black experimental video artist,” she says, in that “there’s a very specific Black American history [with] various signifiers that are not really expressed or seen in her work.”

Instead, Sabur re-centers Black history through a primarily Caribbean lens, “often pulling from landscapes and ideas and languages that are not American, but that obviously have direct ties to her personal history,” Christovale adds. “So it doesn’t always quite register as an American work.”

Jamilah Sabur, Cockpit Country (British Army base 1728-1795) (2021)

Sabur’s work doesn’t register as American for a reason—until recently, she wasn’t one. After moving from Jamaica to Miami with her family, she grew up as an undocumented immigrant, only obtaining her American citizenship in 2018. Her personal struggles with “feeling stateless,” as she put it, have been significant.

In that way, she has often felt like she doesn’t quite belong to either culture. Ultimately, much of her Jamaican identity “has been formed in this relationship to memory, my parents retelling of this landscape of this place,” she said.

In Un chemin escarpé, she uses memory as a way to see “a landscape from another vantage point,” she wrote in an email, scrutinizing how bodies move through and encompass multiple dimensions in time and space.

Sabur creates her art as someone whose perspective isn’t clouded by any ties or allegiances, as though she’s removed enough to be an objective observer, someone attempting to provide answers to questions that those steeped in a single cultural heritage don’t even think to ask.

After getting her BFA at the Maryland Institute College of Art in 2009, she considers her time in grad school at UC San Diego as a real turning point in her practice.

“I went there following the legacy of Allan Kaprow and Lorna Simpson,” she says. What she found “was this program rooted in these conceptual practices”.

That experience continues to shape her thinking, and has led to what ultimately keeps her practice going: the search. Which she is only a fraction of the way into. Similar to how she goes about her work, Sabur takes a bird’s-eye view of her practice as a whole. When asked how she wants it to grow, she wrote: “I just plan to continue this evolution of thought.”