Three and a half years ago, American artist and filmmaker Ja’Tovia Gary was participating in a summer residency in Giverny, the bucolic French commune where Claude Monet spent the final 40 years of his life, when footage of the murder of Philando Castile at the hands of a Minnesota police officer began circulating online.

While protests over the killing and other acts of police brutality erupted in her home country, Gary took a walk through the famed French painter’s beloved garden and considered the overlapping timelines of French colonialism and the rise of Impressionism.

She then became acutely aware of certain “microaggressions,” she told Artnet News: people staring at her, a black person, in a predominantly white region, and men encroaching on her space, uninvited.

“I was a sore thumb standing out,” she recalls. “This unruly, politicized black body in the garden. I was thinking, how can I come here now and assert my subjectivity?”

So she ran through Monet’s garden screaming, disrobing, and lounging around in classical poses.

And she filmed it all, trying to “fingerprint the psychological experience.”

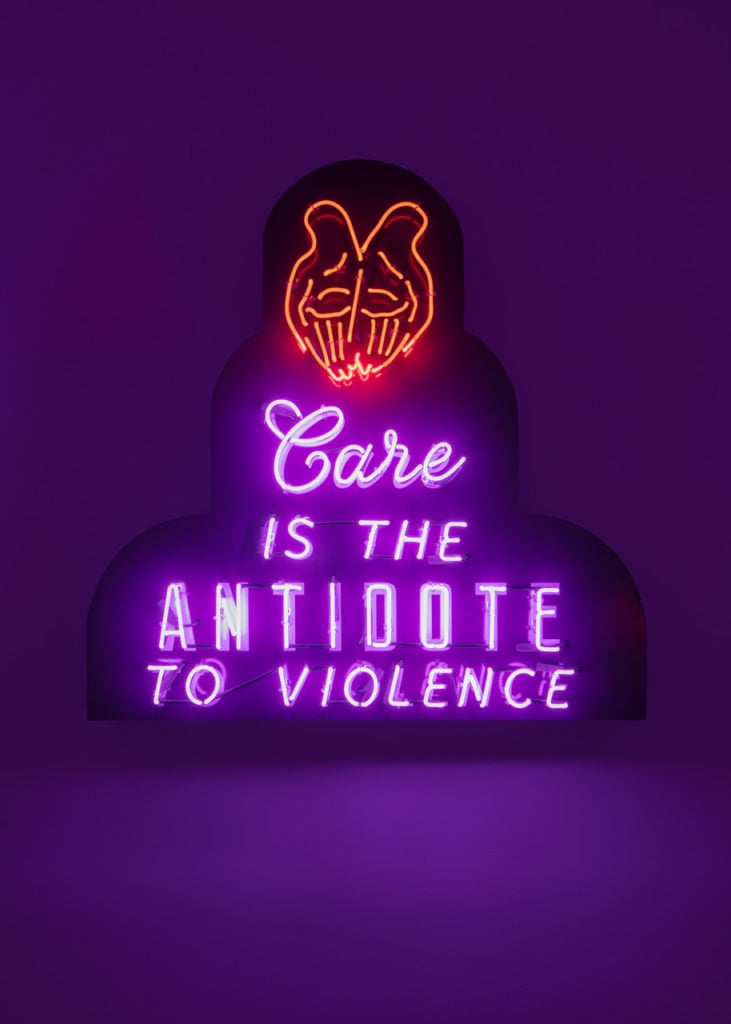

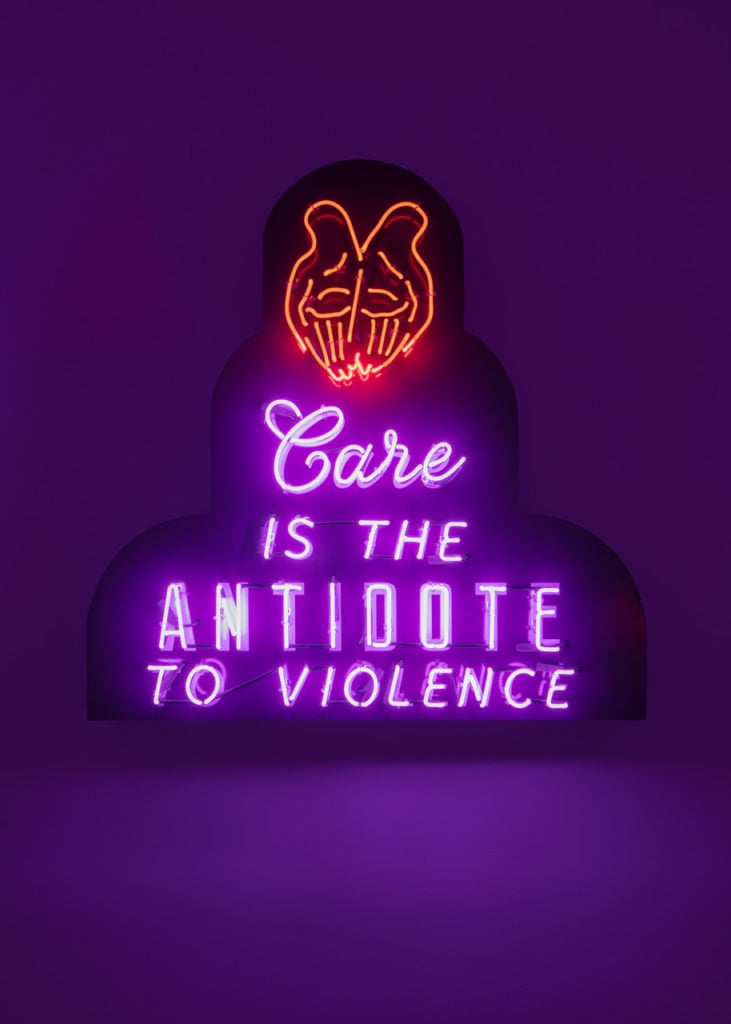

Ja’Tovia Gary, THE GIVERNY SUITE, detail (2019). © Ja’Tovia Gary. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

The resulting footage appears throughout THE GIVERNY SUITE (2019), a three-channel video now on view in her debut show at Paula Cooper and at the Hammer Museum in LA.

The 40-minute film is a hypnotic montage of images, found and original. The shots of Gary in the garden are rhythmically interspliced with footage of drone strikes and an arresting performance by Nina Simone, while in other, Cinéma vérité-style sequences, Gary asks women on the streets of Harlem if they feel safe in their bodies.

As the film lulls you into a kind of trance, the video of Castile’s death, live-streamed at the time by his girlfriend, Diamond Reynolds, jolts you back into reality. It’s edited so that Castile’s body remains unseen in an explicit refusal to indulge in the fetishization of black violence.

Sitting in Paula Cooper office chairs while the show was being installed, Gary laid out the heady mix of references she makes in the film, which nods to experimental filmmakers like Jean Rouch, Fred Hampton’s theory of negro imperialism, and the writings of activist Claudia Jones.

If you didn’t know Gary had a background as an actress, it wouldn’t take long to guess it based on the way she tosses her scarf over her shoulder mid-sentence and enunciates like she’s speaking to a room full of people.

“A lot of people will ask, ‘Well, what does that mean?’ They want a simple definition in terms of what the symbols and the references are doing,” she said. “I can give you answers, but to me that doesn’t mean anything. I want to activate you. I’m trying to move the molecules in the room.”

Ja’Tovia Gary, Precious Memories (2020). © Ja’Tovia Gary. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Sitting in the Director’s Chair

Gary was born in 1984 in Dallas, where she lives now. A performer from an early age, she transferred to the local Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts—a school famous for churning out artists like Erykah Badu and Norah Jones—in her junior year, and devoted herself to theater.

Next was the leap to New York, where she matriculated at Marymount Manhattan College on the Upper East Side. But the move wasn’t easy.

“I was a leading lady in Texas,” Gary said . “And in New York, I’m going to be a servant, maybe? It went from me being Cassandra in the Trojan Women, delivering this gut-wrenching, snot-slinging performance, to me going on MTV auditions and having them tell me, ‘Turn to the left, look forward. We wish you were five pounds smaller.’”

That’s when she decided to move behind the camera.

“Becoming a director was about getting power—the power to fully flesh out blackness and the role of black women in society, to talk about what has been taken from us and what we are coming to reclaim,” she said. “It’s to enliven, to breathe flesh into these tropes, to make them real. That’s what I consider my project to be.”

Ja’Tovia Gary, 2020. Photo: Taylor Dafoe.

She dropped out of Marymount, which was always an awkward fit, and after a couple of years waiting tables, she went to get her degree in documentary film production and Africana studies at Brooklyn College. After that, she pursued an MFA in social documentary filmmaking at the School of Visual Arts (SVA), where again she ran up against the strictures of a conservative curriculum.

“I thought I was going to get kicked out,” she said, explaining her penchant for adding archival footage, direct animation, and other experimental flourishes to otherwise simple assignments at SVA. “They said, ‘We didn’t ask you to do this. You’re actually not following directions.’ And I was like, ‘Directions? Baby, this is art school. Those are suggestions!'”

Her teachers didn’t get her work, but others did. A couple of films she made in grad school, including lyrical portraits of sculptor Simone Leigh and rapper Cakes Da Killa, gained exposure online and went on to be screened at festivals. She also cut the first version of An Ecstatic Experience, a six-minute short that put her on the art-world map.

Featuring Stan Brakage-style illustrations flickering over footage of actress Ruby Dee playing a slave, the film hit dozens of festivals worldwide before being shown in two exhibitions at the Whitney Museum in 2016 and 2017, and again last year in Hilton Als’ James Baldwin-inspired group show at David Zwirner.

It was at the latter venue that gallerist Paula Cooper first saw Gary’s work.

Ja’Tovia Gary, Citational Ethics (Saidiya Hartman, 2017) (2020). © Ja’Tovia Gary. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

The Archive is Alive

“We were profoundly moved by it,” said Steve Henry, a director at the gallery, who brought Cooper to see the show. Shortly thereafter, they invited Gary to the gallery for a meeting that ended up lasting several hours.

“We were immediately committed to working with her after that,” Henry recalled, noting how “incredibly rare” it is for Cooper to take on an artist so quickly. “Ja’Tovia’s a visionary, I think. She has a remarkable way of articulating her vision, both in conversation and in the work.”

Despite several museum appearances under her belt, the exhibition at Paula Cooper, titled “flesh that needs to be loved,” is Gary’s first solo gallery show. As an installation, it’s her most realized effort to date.

Ja’Tovia Gary, Precious Memories (Tower) (2020). © Ja’Tovia Gary. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

At the gallery, a velvety, purple light fills the space, like an abandoned black-light party. A plush parlor couch sits akimbo in the middle of the main space, two legs off the floor, while THE GIVERNY SUITE projects floor-to-ceiling onto three surrounding walls. In a second gallery, there is a makeshift living room where a broken La-Z Boy is positioned before three TVs stacked like crooked vertebrae. The whole thing is like a Lewis Carrollian fever dream projected through the lens of afrofuturism.

For Gary, it’s less about sensorial disorientation, and more about social and historical reality.

“What’s time to black person? It’s just not the same,” she said, explaining her interest the looping structures of blues and jazz and the West African Griot storytellers who recount events non-linearly.

“My work deals with the past as much as it deals with where we are now. The archive is alive and it’s a contested space, just like today. I want that to be felt in the work.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.