When artist Glenn Kaino first met actor and activist Jesse Williams, it was instant creative kismet.

The two recognized in each other a shared interest in art and technology, as well as a desire to give voice to overlooked cultures and pushback against the nuance-free, swath-like narratives that so often serve to summarize whole races of people in media.

And so Visibility Media, the company they co-run, was born. Sitting at the nexus of art and tech, Visibility creates games, apps, and GIF keyboards that specifically cater to communities of color, such as BleBRiTY, an award-winning Afrocentric gaming app that riffs on charades, and the just-launched Ya Tú Sabes, a trivia game that centers Latinx individuals and Spanish speakers from around the world.

Just as Kaino opened his new show at Mass MoCA, which explores unlikely connections between protests across the globe, Artnet News sat down with the two entrepreneurs to discuss how they met, how social justice fuels their creative projects, and why the current state of the cultural world is rife with possibilities for artists of color.

Tell me a little about when you first met. What do you remember about it?

Glenn: I think it was at the [non-profit Los Angeles art space] The Mistake Room. I knew of Jesse’s work, but there was a mutual friend of ours named Joy Simmons, who introduced us—Joy and I have a long history together of starting non-profit spaces. She and I have gotten into some really good trouble together. We started a space called LAX Art, so we’re board members of that, and then The Mistake Room, too. I know that Joy was one of Jesse’s earliest confidantes in terms of learning about the art world in different ways. This community of us were all learning about each other back then. And Joy was like, “You’ve got to meet Jesse.”

Jesse: I remember a very enthusiastic “You’ve gotta meet!”

What made you want to begin working together?

Jesse: The way we started to work together was when I ran up on Glenn when he opened his incredible show in L.A. at Honor Fraser gallery, and there was an app idea around what eventually became EBROJI. Getting to know Glenn was kind of like playing basketball with a guy you know as James, and then finding out he’s James Bond. I knew him as one thing, a really cool, really smart guy, and this brilliant fine artist. And it was like, “Oh, but he also knows this,” and, “Oh, he knows that,” and “Oh, his kids have the same names as mine,” and “Oh, he’s this engineering, digital, software wunderkind,” and “Oh, I can ask him what he thinks about ideas, both creatively and technically and realistically in a world I don’t really know.” So he really became this great sounding board and we just hit it off.

We had a first app idea, which fizzled, but then came EBROJI, which was really fun and ended up teaching us a lot about what it is to make something as a service first, even if the product that provides it isn’t profitable at all. It’s about about changing the landscape and the ground on which we walk, which will not only water stuff for everybody, but provide a more solid ground for the next offering and redefine and reclaim ownership of our own cultural expression, which is a really cool exercise that was both fun and popular. And then we had another idea and another idea, and eventually we said, “Well, shit, we need to form a company because we just keep giving each other ideas and building things together.”

Glenn: I think one thing that helped galvanize our thought process of being in this space was the fact that we were met with a substantial set of exclusionary meetings in the early days, from some of the biggest media distributors, from Twitter and Google and so on. We sat back and said we should think about formalizing this work, because others like us are no doubt facing the same kinds of issues and if we could assist and become leaders in the space as well and show by example, that could play an important role not just for us, but for others like us.

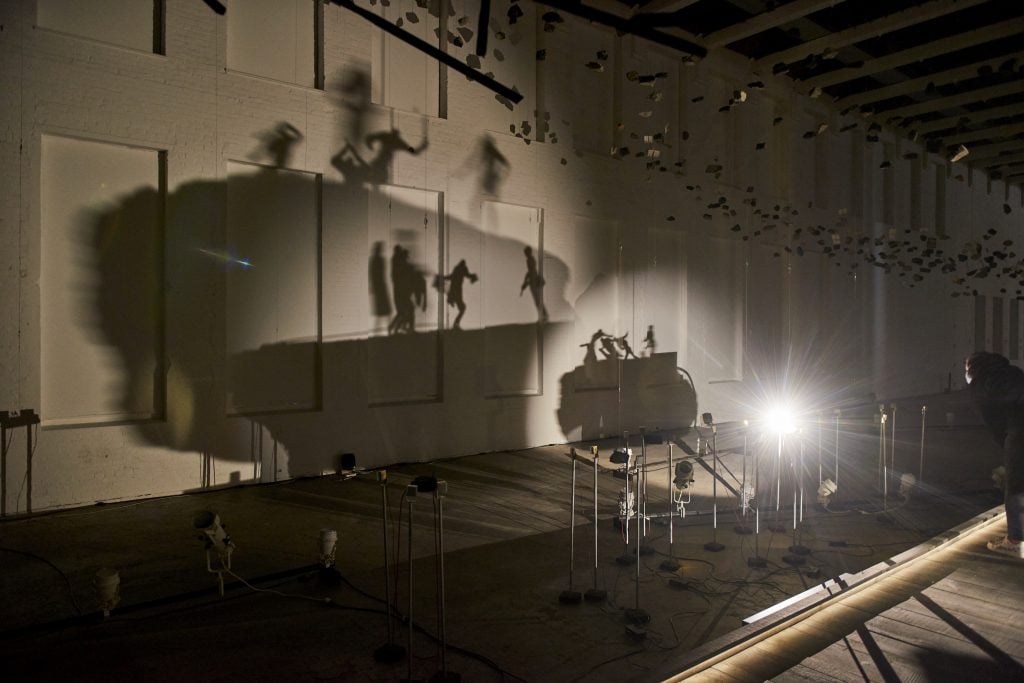

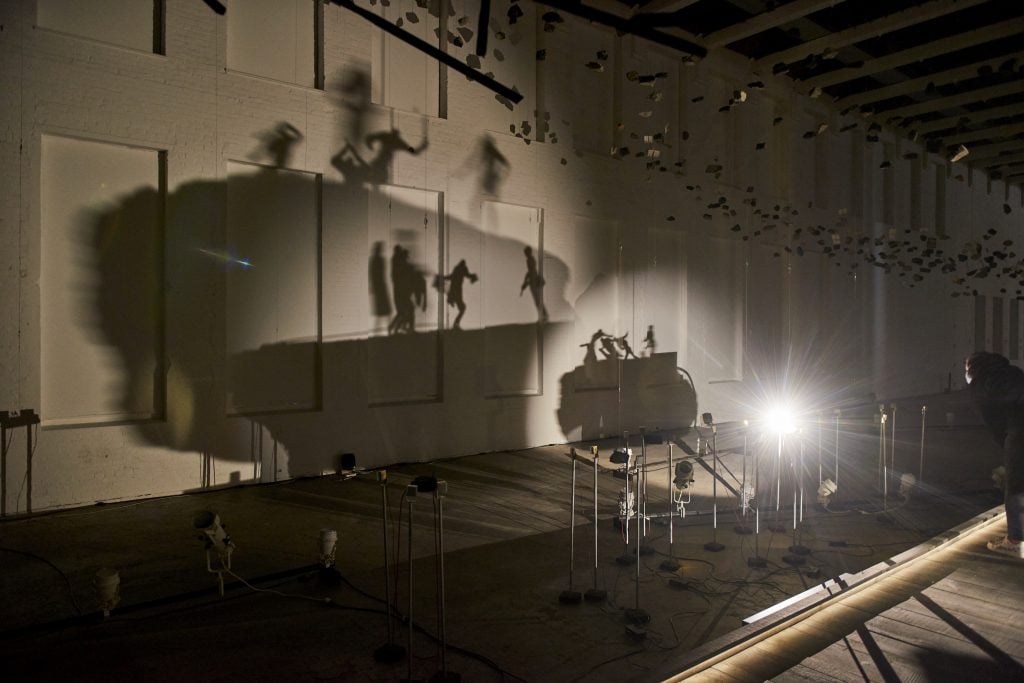

A view from Glenn Kaino’s “In the Light of a Shadow” on view now at Mass MoCA. Photo courtesy the artist and Mass MoCA.

What’s one thing you admire about the other’s creative ethos that you feel has helped you realize all this work together?

Jesse: Glenn’s got this incredible ability to do 20 things at once and do them well, but also calmly, happily, and with air there. You never feel rushed; his stress never becomes your stress. He’s a leader of a very happy staff and work environment. Everything is as it should be. It’s a hell of an example, which really always adds perspective and, frankly, hope that it’s not really about volume. It’s really about who you are and how solid you can be and how efficient you can be with your energy and the value of being truly present when you’re doing something so that it can be fully realized and then you can move on. The difference between compartmentalizing and multitasking, as I understand it, doesn’t really exist. You’re just burning a ton of energy, but you’re not actually working to the best of your ability. So for all of those things, Glenn’s a real example. And I never say these things to Glenn…

Glenn: [laughs] I was gonna say! No, I mean the foundation of our studio is really collaborative. We make sure that everyone is heard and has a voice and it’s not a coincidence that the name of our company is Visibility. I think for Jesse, I’m always impressed with not only his high bar of ethics and the high bar he always brings in terms of his expectations for the work, but also how despite the fact that he’s juggling myriad projects in a bunch of spaces—tangible activism, board leadership, and nonprofit stuff, all the way to being on very popular TV shows and in films—an unshakeable level of clarity still exists throughout the spectrum of his work. It’s a rare thing, because it also has bite, which a lot of people who purport to have politics and can speak a little bit of the language kind of express themselves in that way, but to be able to speak with that level of precision is just incredible. I will say this, every time Jesse comes to the studio and speaks, everyone’s like, “Damn! How does he stay so clear? He’s so smart.’”

For me as an artist, I like to attack ideas from the edges. And I sort of speak in meandering ways and hopefully land in a poetic space, and I think that what Jesse has is a very poetic clarity through which he’s able to say things that are super precise.

You’ve both worked in various art and art-adjacent disciplines, from visual art and architecture, to filmmaking and acting, to conceiving apps that feature prominent art components. What has it been like collaborating across disciplines? And what, in your opinion, makes a project between collaborators from different fields successful?

Glenn: All of our work starts with intention. While we met each other through the art and media worlds, we both have backgrounds in education. Jesse has a longer background as an educator, and I was a college professor at USC and UCLA for a little bit, and we both have dedicated our lives and practices toward elevating the dialogue of social justice and equity in several ways.

Both of our practices allow for that in the sense of, we’re here to attack the issues and the problem, but we’re also very fun producers of experiences and we’re up for different challenges. So I happen to have experience making apps. We were in a conversation about language and the EBROJI app came out of identifying a need. Back when we made EBROJI, emojis were little yellow characters and there was an outcry for expression right at the time when Apple was diversifying emojis and there was a diversification conversation more largely and the GIF landscape was just taking shape. Our effort there was really language-specific. We wanted it to be as successful as it could be for the purposes of expression, and I think all our work comes from that sense of pre-established intention, whether it’s the art and film work we’re doing with Tommie Smith or making a GIF keyboard.

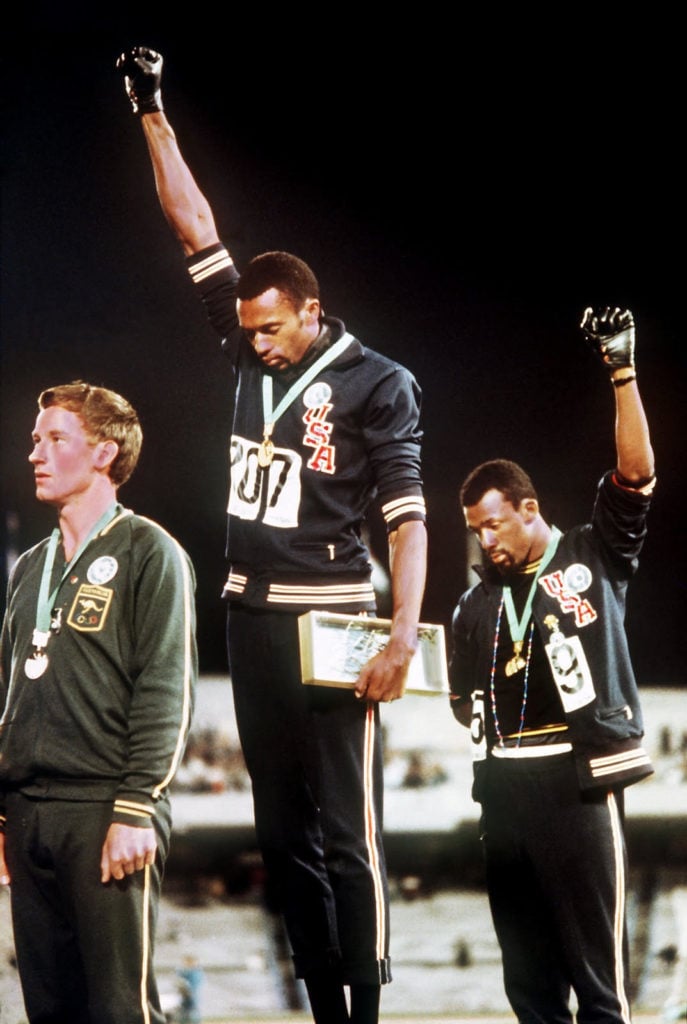

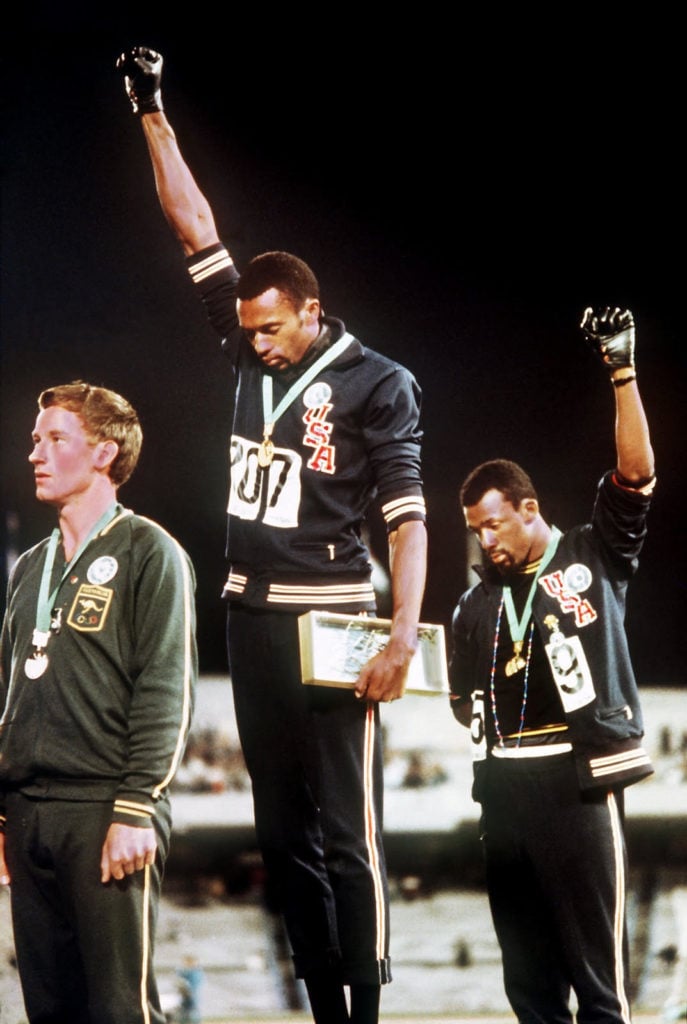

Tommie Smith (center). ©Time and Life Pictures/Getty Images.

Jesse: Yeah. That word “intention” it’s so popular right now, and it can mean different things to different people, but I think we have really been able to start, act, and finish with an intention and goal being centered at all times. There are other things I do for money. There are other things I do “for my career” or for my passion or because it makes sense for my family. But doing this work is feeling like sometimes you just have the code. If I’m pitching you an idea I have for a movie, I want the response to be that you get it right away. Almost the best thing I could hear is, “How does this not exist already? This is such a good idea!” Often when we have these ideas, the seas part and it makes sense, we’re the best people to do it, and it’s not really being done, and we also have the equipment and acumen and energy and facility to do it well and happily. Our meetings are happy and lively and we’re feeling titillated and jotting stuff down and brainstorming. It’s really just fun.

I forgot who said it, but someone said that you shouldn’t be able to make much of a distinction between work and play. They should blend and bleed into each other. I think that’s what fuels healthy and exciting and stimulating partnerships. And then we get to have conversations about it. I get to talk to my white coworkers about my Black-centered app, which they might feel isn’t for them and then I get to say, “It’s totally for you,” as much as everything else in the world is or isn’t for me. But it’s positive energy. You can find yourself parsing through challenging concepts and still keep it centered around love. In the same way that Glenn is Japanese-American and from the hood, I come from a very unique background as a biracial person from a lot of places. All of us, the non-white class of our generation, certainly not in the last 30 years anyway, haven’t felt like we’ve seen each other really represented in media. There’s the lower-class economic strata version of us; and then there’s the president. There isn’t really the three of us in this conversation—sophisticated, interesting, well-traveled people with some healthy relationships, some dysfunctional ones, some obstacles, joy, and family—in the same room. You don’t see us together on TV shows or in a group of news anchors in media. So that’s a big deal and that’s what fuels us, to be able to show that and say, “We exist and we’re doing this because nobody’s going to do it for us.”

Right.

Jesse: But to be honest, I think that also exists in whiteness. I think with the polarity of politics right now, there is this class in whiteness that’s not represented, which is to say there are perfectly functional white people with privilege that can and do talk about and acknowledge racial issues and it’s fine. They’re not fucking terrified and precious and red-faced and embarrassed about it—they know it exists. Just like men should be able to talk about rape culture—it exists and we need to talk about it and demand better. It’s like if white people make a charades game that seems race-agnostic, but is actually very white, they don’t have to claim that, but we find a way to play it, just like we find a way to see ourselves in every show in the history of television. It doesn’t have to have us in it, but we find a way to relate.

What are you focused on at the moment that’s inspiring you? How is that influencing the work you’re doing now and what you’re planning in the near future?

Glenn: We are working on a new game, but we just launched one called Ya Tú Sabes with a partner friend of ours, Arturo Nuñez, who has an extensive sense of history of bringing conversations to Latin American markets. As an extension of our success with the BLeBRiTy app game, we wanted to expand that, and that’s been very exciting. Jesse’s been doing a lot of press about that recently.

Jesse: We’re expanding into a new comfort zone and getting global. Our first two products are generally domestic-focused, but we have a global perspective as people and that’s leading into products in our willingness to engage the knowledge that’s influenced us and speak with distinction. There are so many distinct forms of Latin American culture, just like folks from Appalachia are not folks from Seattle or Silicon Valley or Houston. So we are including them and they touch our world and affect what we say and how we eat and think and dance. So why not include them?

Glenn: We also have a new game that we’re working on right now called Homeschooled, which will be out soon.

Jesse: I’m so excited for that, it’s a big one.

Was that influenced by the pandemic?

Jesse: We can’t fully talk about it yet, but I will say that is a fair and good question, and the idea came well before, but we real-time updated it for the needs and experiences of what we’re all going through now.

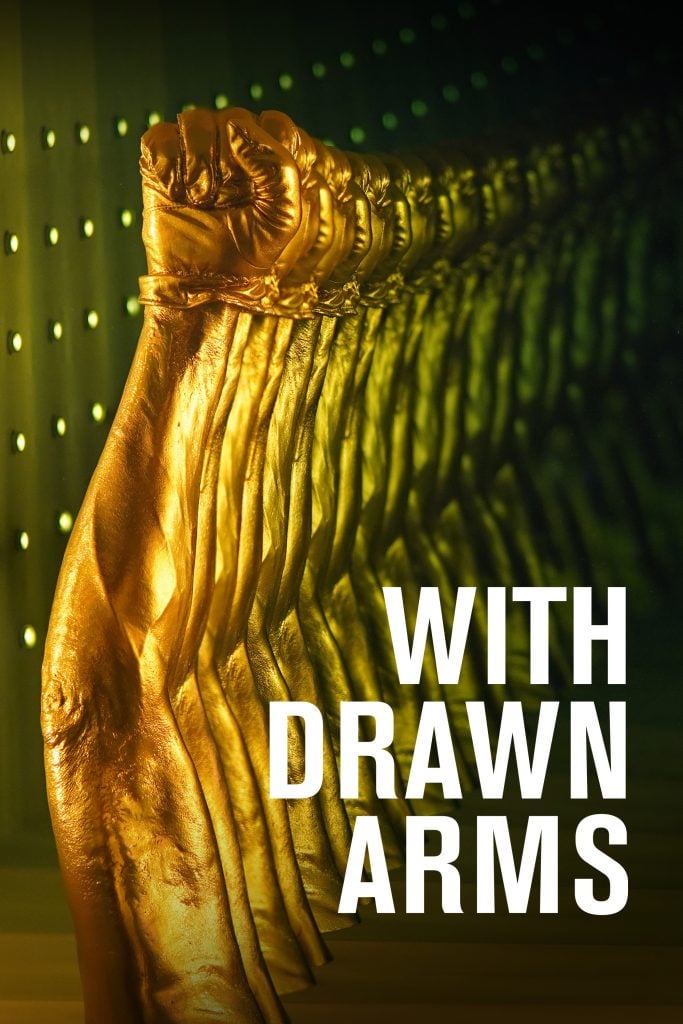

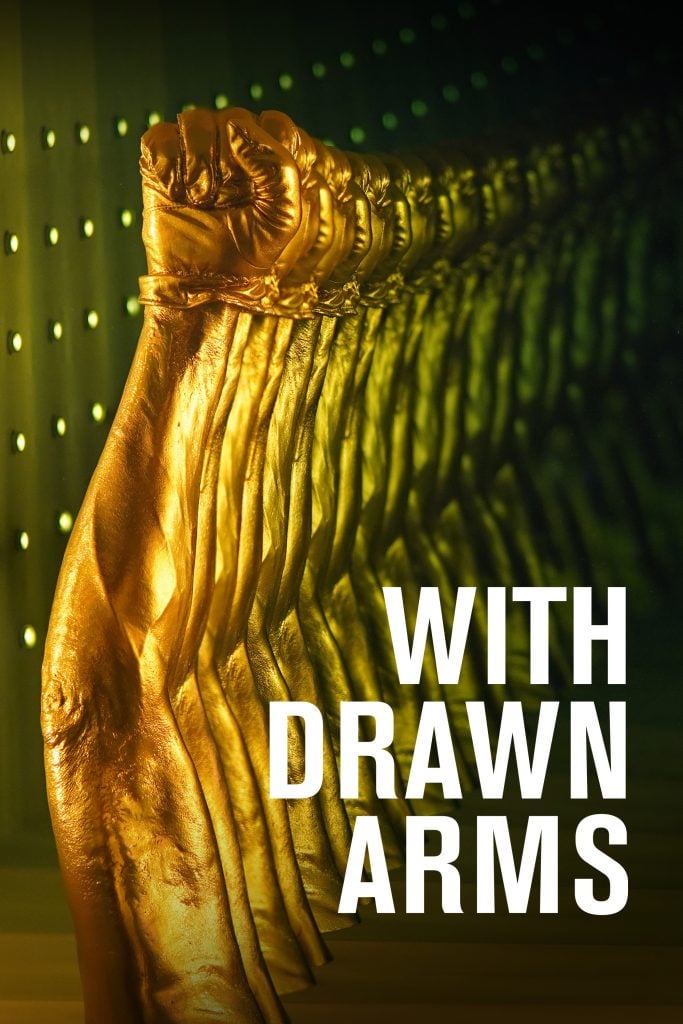

A film poster from “With Drawn Arms” (2020). Photo courtesy of Glenn Kaino.

As we’ve discussed, activism and social justice have informed your career trajectories and are very much at the root of a lot of the work you both do, together and apart. Glenn, how do those subjects factor into With Drawn Arms, your ongoing art and film collaboration with former athlete Tommie C. Smith, and your new show at Mass MoCa?

Glenn: I think that for both projects it’s a dual approach, particularly in this current frame of heightened awareness of violence against Asian Americans. The work I’ve been doing with Tommie Smith is almost a decade long, and it’s a long-term, collaborative project that has operated from several vantage points. The first is the initial time we met, which resulted in me helping him to bring his story forward into the present and connect it to the athlete activism of the day, and to tell a complex story about Tommie when everyone knows him for just that image. We’re also modeling a sense of intersectional collaboration and allyship. Jesse and I have been on some really fun Zooms with him recently for the film.

And so the same thing kind of applies to this show at Mass MoCA, which originally started with me having dinner years ago with Gerry Adams, who at the time was the president of Sinn Féin and the IRA, but also me being able to meet and hang out with John Lewis before he passed and hearing, in tandem, Gerry’s story of Bloody Sunday in Northern Ireland and hearing about Selma from Congressman Lewis and engaging them actively in that conversation. For the show, we worked with the Bloody Sunday Trust and the John Lewis Foundation to actually create material. What I like to say is I use art and ideas associated with art to connect things that don’t really have a chance to meet in ways that tell stories to reveal ideas that might inspire others to understand that we’re all connected and we’re all in this struggle for equity together. And so to answer the question, for me, art provides that space for new ideas to be brought into the world without judgement. It has a good amount of appeal for people from all different cultural stations.

Jesse, how does the expansion of voices from a new generation of artists of color, in your view, influence the dialogue about who gets to make culture?

Jesse: It’s a little bit like, “Be careful what you wish for,” because there’s always been this kind of vacancy, this token or chameleon role for non-white folks here trying to create or express or climb any ladder and be safe and seen at the same time. So once you get over the temporary allure of being the only one in what you’re doing, you say, “Shit, I wish there were more of us so that I don’t have to be the only example” of what it means to be whatever it is. You don’t have to have the pressure of over-representing your entire community when you’re just an artist trying to make something. It’s like, “I don’t even get the privilege of being able to just make, because I have to represent 20 million people and that’s not possible in a healthy way and it can feel like an honor but it can also totally sabotage everything.” And you’re dealing with that while everyone else gets to walk around and just pursue their hobby and fail and try something else. But right now, being able to see so many creatives, from media and fine art for example, is great. Instead of one director, you’ve now got 20, and instead of four channels, you’ve got 400. So the burden gets a little less and a little less and little less over time, and so I’m feeling like I can be closer to myself. I’m not quite myself yet. But I can be a little closer to myself, and be a little weird.

We have these gnarled, habitual reactions to things and we’re starting to kind of loosen up and have some joint relief. It’s like, “Oh, that’s actually fine, her hair is a little different, and that’s the way she talks and I’ve never known anyone that looks like her that was raised in Sri Lanka, and that’s interesting.” We’re better with that now. We’re just expanding and the world’s consciousness is expanding and it’s unstoppable. I would also say that as somebody who grew up in an activist house and community, there is very much an awareness about this urgency of “now.” “Fix things now, lives are at stake, and it’s all very urgent.” And that’s all true, but it’s also kind of nice to zoom out occasionally and remember that empires rise and fall, that we change over time, and it’s okay to get back to some of that calm so we can actually be present for some of the other things we’ve talked about and remember the joy in it and not create out of fear. It’s just such an amazing time to be alive and watch, so to speak, the prelude to the renaissance.

Glenn: Did you just make that up…? Did you just make up “prelude to the renaissance?” This is what I’m talking about! He’s so good! [all laugh]

A view from Glenn Kaino’s “In the Light of a Shadow” on view now at Mass MoCA. Photo courtesy the artist and Mass MoCA.

I’m going to end on the silly question we always ask for these things, so here goes: if you could switch lives for a day, if Glenn you were Jesse, and Jesse you were Glenn, what’s one thing you would be excited about?

Jesse: I’m in a stage where I have a lot of irons in the fire. I’m in a leadership position for about five or six businesses, and I’m on a show and developing other projects in film and TV and writing. I have a little bit of a staff, and I’m perpetually tired, but also perpetually inspired and excited and adding more things, despite my therapist’s suggestion. Like I indicated before, and I know because I get to see it day-to-day, Glenn is a terrific leader of people and everybody is brought into his process, so I would really love to get in the cockpit and just see how his whole thing moves so smoothly and get over some of my personal hurdles and obstacles. I’d like to learn how to add structure to make things happen so they’re not as… DIY. So that would be cool to figure out how he’s tangibly able to get so much purposeful, lasting work done with other happy, skilled, and unique people.

Glenn: He took my answer. No, I think we get along because we have similarly constructed lives, if you swap out a big museum show for a long-running TV show or film. I was laughing because I’m like effectively “on set” in a remote location and I’ve been here for a month and a half so it’s a very similar circumstance. For me, I think I’m always really enriched by the level of knowledge and culture he has. We meet in a space; we come from different spaces, but for me I think we’re both voracious learners and to have access to Jesse’s world of histories and everything he knows would be a really remarkable thing.