Art History

Robert Rauschenberg Made the First-Ever Earth Day Poster—Here Are 3 Fascinating Facts About How He Conceived the Powerful Image

Happy 51st Earth Day!

Happy 51st Earth Day!

Katie White

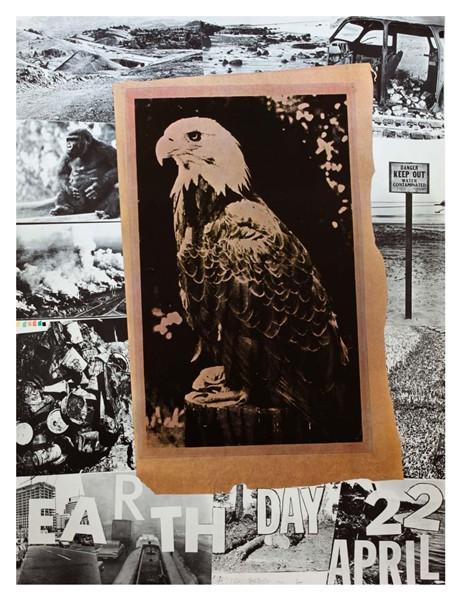

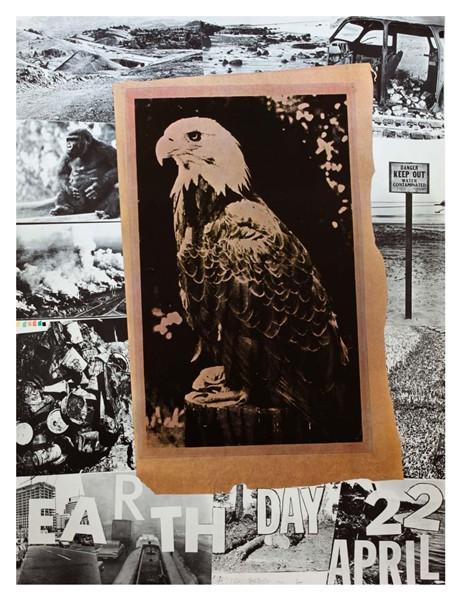

Here’s a fun fact for anyone who ever made a middle-school Earth Day poster: Robert Rauschenberg made the very first one for the very first Earth Day, which was celebrated on April 22, 1970.

Besides being one of the most innovative artists of the postwar generation, Rauschenberg was also a devoted environmentalist, who in his lifetime made numerous posters and prints to support causes close to his heart, of which this was the first.

His environmental advocacy may come as a surprise to some. Even today Robert Rauschenberg’s life and legacy are primarily linked to the urban grit and dynamism of downtown New York City in the 1950s and ’60s, where he first found fame.

But for more than 40 years of his career, he lived and worked off the coast of Florida, buying a home on sunny Captiva Island. Here, Rauschenberg found rejuvenation and new inspiration: he wrote in 1970 that Captiva was “the foundation of my life and my work; it is the source and reserve of my energies.”

Rauschenberg was tapped to make the poster after a massive oil spill off the coast of Southern California in 1969. Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson proposed Earth Day on April 22, 1970, as an initiative to bring awareness to the dangers of pollution, about which this poster would spread awareness. The image was also for sale: 10,300 of them were printed by Castelli Graphics to benefit the American Environment Foundation in Washington, D.C.

Formally, Rauschenberg’s Earth Day poster shows a bald eagle, a symbol of the United States, at its center. The eagle is washed over in muted tones of brown and rust, which convey a sense of environmental contamination. Surrounding the eagle is an array of jarring and disparate images: burnt-out cars littered with detritus, a gorilla (an endangered animal of the generation), sullied waters, aerial views of highways scarring landscapes, and smoke billowing from industrial factories.

The image is characteristically complex. So to celebrate Earth Day 2021, we found a few facts about Earth Day (1970) that might illuminate its significance.

Crude oil stills and can factory, Port Arthur Texas, U.S.A. Photograph Keystone View Company. Courtesy of Wikimedia.

Oil fields, derricks, and smoking refinery towers are dotted throughout Rauschenberg’s oeuvre. These images, and the oil spill that inspired the creation of Earth Day, were more than just fragments culled from Rauschenberg’s imagination.

Rauschenberg was born in Port Arthur, Texas, in 1925. The city, just off the Gulf of Mexico, has been an oil town since the late 1800s, and is today home to the Motiva Refinery, the largest oil refinery in the whole of the United States. Barely at sea level, the city was susceptible to the devastation of hurricanes and the economic boom and bust of the oil industry.

Rauschenberg said that growing up, he hated the industrial smells that billowed out of the refineries, filling all corners of his childhood life. Notably, in his Canto VIII: Circle Five from the “Dante” series illustrating the literary Inferno—and completed soon after moving to Captiva Island—he depicted Dis, the capital of Hell, filled with oil derricks within a cloud of flaming colors.

Robert Rauschenberg, Canyon (1959). Image: Ben Davis.

As evidenced by his Earth Day poster, Rauschenberg’s charitable prints were not particularly didactic, but challenging, atmospheric, even contradictory. After the artist made a print supporting public transportation, labor advocate and mediator Theodore Kheel praised Rauschenberg’s approach to such projects, saying, “it assessed neither blame nor praise.”

These complexities shine through in Rauschenberg’s material choices and his imagery. The bald eagle at center inevitably calls to mind the artist’s iconic work Canyon (1959), which itself prominently features a taxidermied eagle he’d been given at its center—an allusion to the Greek myth of Ganymede.

That work, like all his combines, is made from the industrial detritus and varied garbage that intermix into the background of his poster. Rather than passing judgment, images like Earth Day place the individual, and the artist, within the complex swirl of realities, and let each person assess their own role.

Robert Rauschenberg at work in Florida. Courtesy of Getty Images.

During the years leading up to his Earth Day poster, printmaking had taken an increasingly central role in Rauschenberg’s practice. For the artist, the poster medium, in particular, carried social and democratic significance by inviting a much wider audience into his art. The Earth Day poster marked the first in which Rauschenberg employed the medium for public advocacy, and initiated an important shift in his understanding of his role as an artist.

His advocacy coalesced with a variety of innovative print techniques. In 1970, he invited Robert Petersen, an assistant printer at Gemini G.E.L. with whom he had collaborated on the “Stoned Moon” series from 1969–70, to live and work on Captiva.

With Petersen, Rauschenberg printed his Earth Day Poster as a large lithograph in an edition of 50, produced by Gemini G.E.L. in Los Angeles. In 1971, having purchased a home in Captiva to function as a print shop, Rauschenberg and Petersen founded Untitled Press, Inc, through which the artist would experiment with ink transfers and various innovative printing technologies.