People

Jimmie Durham, Whose Trenchant Art Needled American Identity and Colonialism, Has Died at 81

The artist's work about the role of Native identity in American culture gained him wide acclaim and pointed scrutiny.

The artist's work about the role of Native identity in American culture gained him wide acclaim and pointed scrutiny.

Julia Halperin

Jimmie Durham, a performer, sculptor, activist, and writer who resisted easy categorization in both art and life, has died. He was 81.

The news was confirmed by his gallery Kurimanzutto in New York. The artist died in his sleep on Tuesday night at home in Berlin due to a medical condition, a representative from the gallery said.

From a sculpture made by dropping a nine-ton volcanic boulder onto the roof of a black Chrysler, to figures assembled from New York street trash accessorized with “Indian” touches, to a parody film about what it’s like to be discovered as an artist, Durham made art that blended incisive political and cultural commentary, humor, and wit.

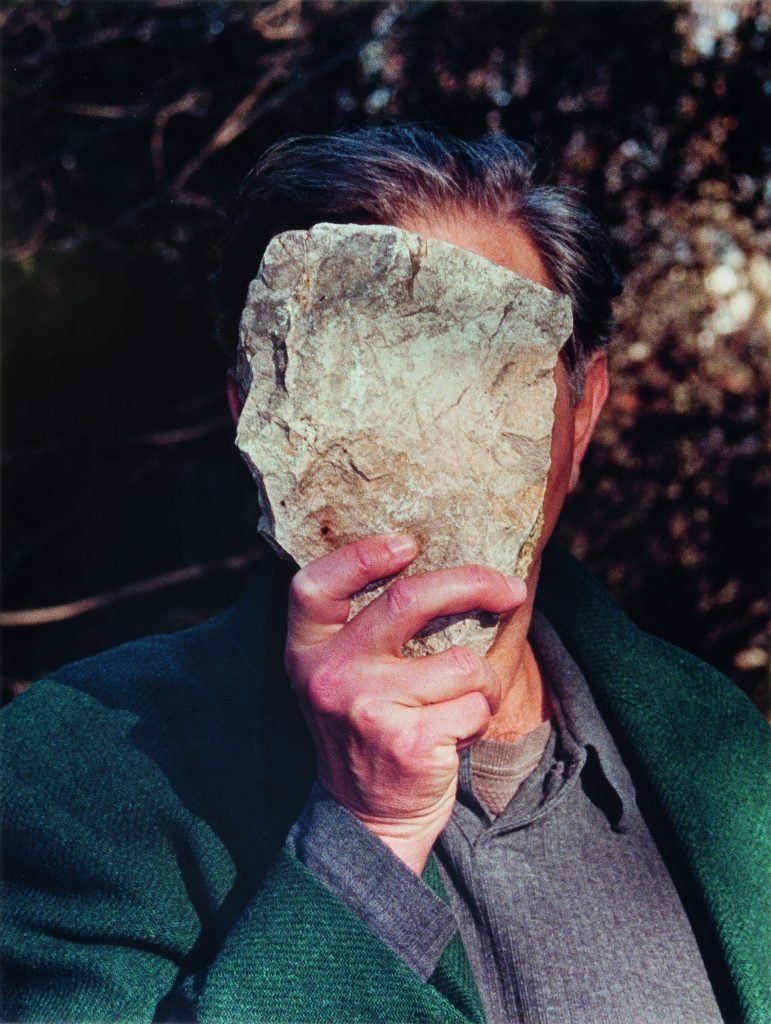

Jimmie Durham, Self-Portrait Pretending to Be a Stone Statue of Myself (2006). Courtesy of ZKM Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe.

He is perhaps best known for making art that examined the legacy of colonialism and the role of Native American identity in American culture. It is this work that gained him wide acclaim—but also pointed scrutiny.

When a major traveling U.S. solo exhibition opened in 2017, it reignited a debate over whether Durham, who was not a recognized or registered member of the Cherokee tribe but self-identified as Cherokee, was capitalizing on an identity he had no right to claim.

Durham, for his part, resisted that label and any other. “I’m accused, constantly, of making art about my own identity,” he said in a 2011 interview. “I never have. I make art about the settler’s identity when I make political art. It’s not about my identity, it’s about the Americans’ identity.”

Over the course of his celebrated career, Durham appeared in most of the world’s important contemporary art exhibitions—more than once. (His official CV is 25 pages.)

He won the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the 2019 Venice Biennale, having appeared in the exhibition’s 1999, 2001, 2003, 2005, and 2013 editions. Durham participated in the 1992 and 2012 Documenta exhibitions in Kassel, Germany, and the 1993, 2003, and 2014 Whitney Biennials in New York.

Jimmie Durham, Brown Bear (2017). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

“Jimmie was an artist, a poet, an activist, a teacher, a singer, an insatiable reader, an unconditional friend, one of a kind,” Kurimanzutto said in a statement. “Jimmie loved life, his imprint in this world is deep and his influence will undoubtedly forever stay with all of us fortunate enough to meet him, as well as those touched by his words, his art, and his activism.”

Durham was born in 1940 in Houston, Texas (despite his own account that he was born in Arkansas). His artistic career began with an interest in the intersection of the civil rights movement, theater, and writing in the early 1960s. He held his first performance at the Arena Theatre in Houston at the age of 23.

After a stint in Geneva, where he studied at the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts, Durham returned to the United States. Inspired by the American Indian Movement’s 70-day occupation of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, he joined the group as a full-time organizer in 1973. He later became director of the International Indian Treaty Council, where he campaigned for U.N. recognition of Native sovereignty.

In part due to disagreements with the movement, he returned to full-time art-making in 1980. Over the next two decades, Durham produced trenchant assemblages, poems, and essays that needled the reductive white American narrative of Indian identity.

One of his most-reproduced works, a 1986 self portrait, depicts the artist as a flat canvas cutout—traced by his partner, Maria Tereza Alves—inscribed with contradictory statements and adorned with synthetic hair, a chicken-feather heart, and a colorful wooden penis. (“Indian penises are extremely large and colorful,” one of the phrases on his body reads.)

Jimmie Durham, Self-Portrait Pretending to Be Maria Thereza Alves (1995–2006). Courtesy of ZKM Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe.

Durham’s experience as an artist in New York City during this time, when a call for multiculturalism defined cultural discourse, informed his skepticism of ethnic labels. “I am not an ‘Indian artist,’ in any sense,” he said in 1991. “I am Cherokee but my work is simply contemporary art. My work does not speak for, about, or even to Indian people.”

From 1994 onward, Durham lived in self-imposed exile from the United States, moving from Dublin to Rome to Naples before ultimately settling in Berlin with Alves.

Durham was the subject of solo shows at the MAXXI Rome in 2016, the Serpentine Galleries in London in 2015, and the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels in 1993. In 2017 and 2018, the retrospective organized by the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, “Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World,” traveled to the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Remai Modern in Saskatoon, Canada.

American artist Jimmie Durham at the Biennale of Sydney. (Photo: GREG WOOD/AFP/Getty Images)

He received the Goslarer Kaiserring—the emperor’s ring of the German city of Goslar—in 2016 and the Robert Rauschenberg Award in 2017.

In a 2017 interview, the artist said he “did leave home deliberately and have been accused of not being part of any Indian community, and that’s certainly a correct accusation.” But what he embraced about living in Europe, he said, was the fact that he could “never be any nationality, not of the Cherokee nation or any other nation… These days, it sounds stupid to say I’m a citizen of the world. I don’t think I am a citizen, I think I’m a homeless person in the world, and I like to be that way.”