Art World

At 84, Joan Snyder Keeps Creating Bold New Work

With six decades of groundbreaking work behind her, the feminist art icon presents a powerful new survey at Thaddaeus Ropac in London.

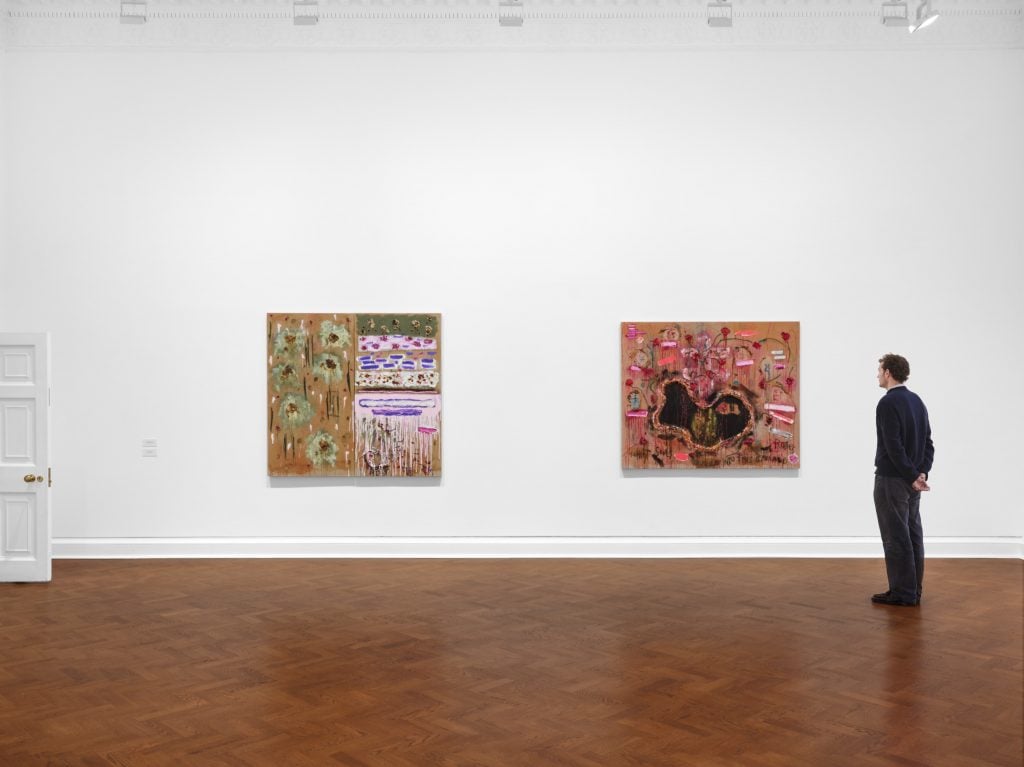

Late last month, Joan Snyder sat on the ground against the wall in Thaddaeus Ropac’s stately London gallery, her elbow leaning on a bent knee. Around her, hung eight paintings she completed within the last nine months, pulsing with the artist’s signature, expressive maximalism. They are part of her first solo exhibition with a blue-chip gallery, a survey covering 60 years in over 30 paintings. “Don’t call it a retrospective, because I still want one,” Snyder says. And boy, does she deserve one.

“Body & Soul” is on view until February 5, 2025. It proves that at 84, Snyder is making some of her best work. “No one is more surprised than I am that I keep having these ideas, and keep making these paintings,” she said. “It’s kind of magical.” The painting Roses for Souls (2024) was hanging above us. In it, a black organ or amoeba-like pond splattered with gold glitter is surrounded by floating, scratched faces. Known for incorporating other materials, fleshy, dried roses, paper mâché, and straw take shape alongside hovering, short and thick pink brush strokes that drip down the length of the canvas. She painted it while thinking of the war in Gaza, and it is a rapturous example of her raw landscapes, which she artfully balances between careful composition and dripping, messy, unleashed freedom.

In these works, and across Snyder’s life’s practice, beauty in nature, visceral color, pain, and loss heave back and forth. Narrative qualities can be read in detail, sometimes appearing as open-book, split-down-the middle diptychs in her latest paintings, but her art has never offered a specific storyline.

© Joan Snyder. Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London · Paris ·

Salzburg · Seoul

As for the effort involved, Snyder, whose face is framed by a round puff of silvery, wayward curls, was more concerned about her opening later that evening. “The difficulty is going to be the gala dinner tonight,” she said. “This is easy, and you can quote me.”

Snyder is better known in the US, and relatively unknown in Europe. She first drew stateside attention for her “Stroke” paintings of the 1960’s and 1970’s, with their stacked and undulating brush marks that sometimes float on pencil-lined canvas. She also became a recognizable voice in America’s feminist, artistic movement. But the fact is, she should be a household name, equivalent to male contemporaries like Cy Twombly or Anselm Kiefer, whose artworks share certain formal qualities with hers, though their differences run deeper. Evidently, that isn’t how things went, but more on that later.

Joan Snyder:Body & Soul, installation view at Thaddaeus Ropac London, 2024. Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London ·Paris · Salzburg · Seoul. Photo:Aggie Cherrie.

About her process, Snyder explains her recent works took longer than the “Stroke” paintings, seen in the chronological show. “When I go into the studio, it just happens,” she says. “They take a while to build up, because there are different layers I have to work on, but I easily put myself on automatic pilot. Turn up the music and go.” Before that, she also prepares with rough sketches, made in response to live music— Bach, Arvo Pärt, Requiems, Philip Glass, opera, jazz, are some favorites. “I can hear it,” she says of the way she thinks about painting. “It makes a sound to me.” Once a sketch has gestated, sometimes for years, she paints it, and something else emerges.

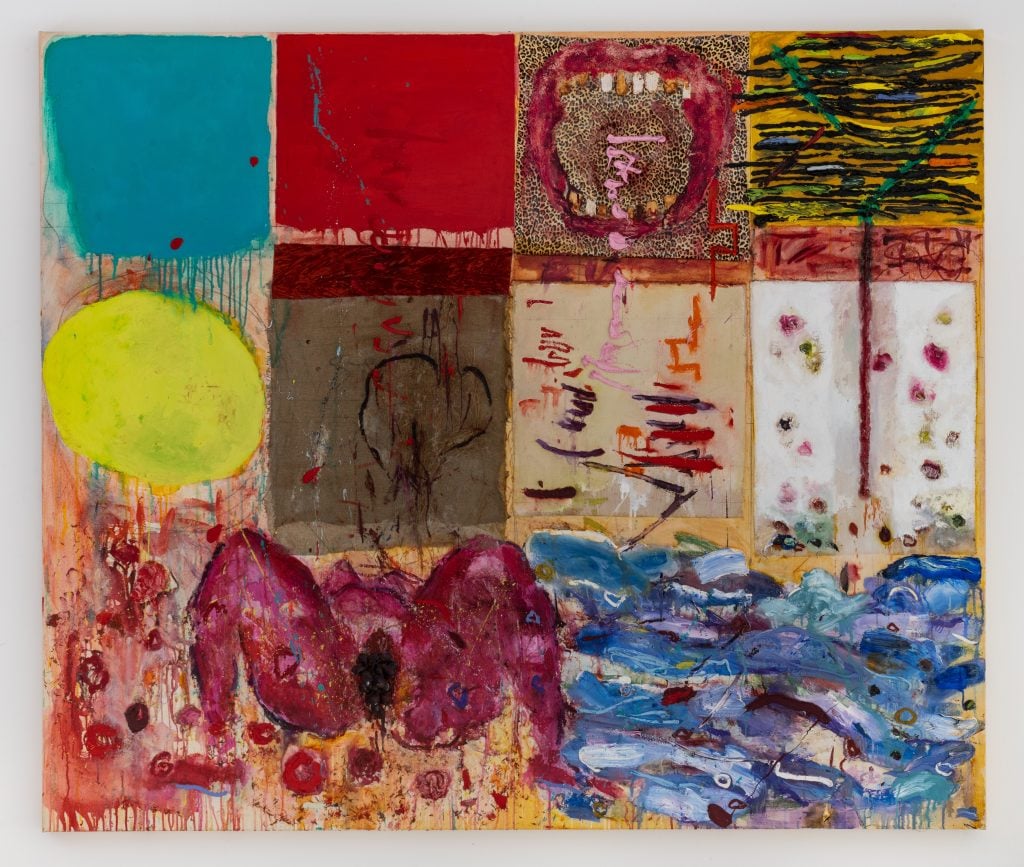

Always, recurring metaphors appear in layered paint and collage, like a personal, visual language. They include roses, hearts, various grids, mud, animal prints, scribbled writing, sheela na gig figures with plastic grapes hilariously stuck to the crotch, flock, and open, gaping gashes in fabric, to name a few.

Body & Soul, (1997-1998) Photo: Adam Reich. © Joan Snyder. Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London · Paris · Salzburg · Seoul

“When I started painting it was literally like speaking for the first time. I could just express myself, and I think I’m still doing it,” Snyder said in an earlier talk from her Brooklyn home. She suffers from anxiety, which has hampered her verbal expression to a degree—she speaks with a witty, New Yorker punchiness, and hints of a certain Yiddish humor. Nevertheless, Snyder says her words only scratch the surface, while her paintings are a whole other ballgame. “When I’m in a group of people,” she says, “I can never say what I want to say. In the studio you’re alone, and you can really talk.”

She discovered this during a “magic moment,” while at Douglass College, where she was majoring in sociology, and finagled her way into a painting course at the Rutgers University campus, without “all the mishegas” or “craziness” of a 101 art class. She knew little about art then. “I was literally culturally deprived,” she said. “I had never been to a museum. My parents were working-class, lower middle-class. Nothing horrible about it, it’s just that I didn’t know anything.” Her teacher introduced her to German and Russian Expressionist painting, which spoke to her background. “It opened a whole world for me,” she said.

To her mother’s dismay, she took the next year off, rented a studio on the river in New Brunswick, painted the first half of the day, and worked as a social worker for the remainder. “I knew that painting meant so much to me at that point,” she remembers. “I knew that one day I would be a good painter.”

Joan Snyder:Body & Soul, installation view at Thaddaeus Ropac London, 2024.Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London ·Paris · Salzburg · Seoul.Photo:Aggie Cherrie.

Early signs were there. Snyder enrolled in an MFA program at Rutgers, at a time when Minimalism and Color Field Painting were the rage. Her teacher was the Minimalist Robert Morris. “Everyone in class was making small, gray boxes, except me. I was making the craziest sculpture,” Snyder remembers. It was a life-sized, plywood cutout angel, her legs parted in the same sheela na gig form she would return to later, with big wings on a rolling platform with plastic roses stuck on it. Morris said that if it were up to him, he’d stick it in a closet, and only look at it every few decades, but Snyder was undeterred.

“I wanted more, not less. I wanted the kinds of things that I found in music. I wanted sorrow, I wanted joy, I wanted tragedy. I wanted a lot of things in a painting that I never found in those Minimalist and Colorfield paintings,” she sys. Still, Snyder was never motivated to work in direct opposition to any prevalent, male-dominated art movement. Though influenced by the liberating feeling of Jackson Pollack’s paintings, inspired by Hans Hoffmann, and aware of other women artists with whom she was in a feminist “consciousness-raising group,” Snyder worked somewhat on the periphery. She could be reclusive and spent long stretches in the countryside.

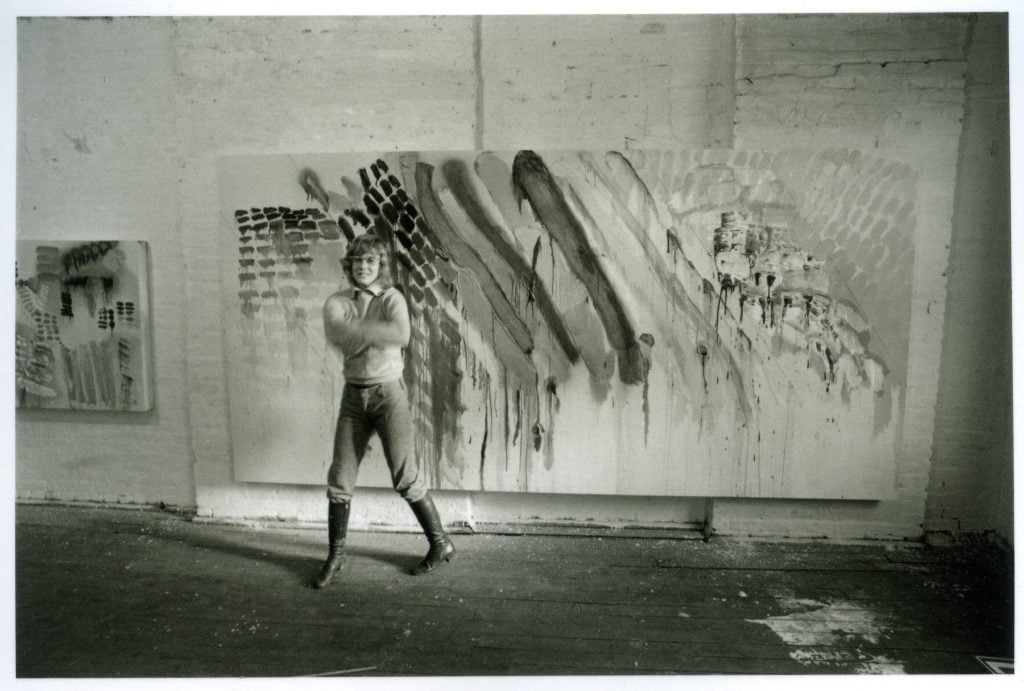

Joan Snyder in her studio. Credit: Larry Fink. Courtesy Joan Snyder.

She was alone in her New York studio one summer in 1969, while everyone else she knew was grooving at Woodstock, when she made Lines and Strokes, the first “breakthrough” painting, which had to do with discovering “the anatomy of a stroke,” its “richness,” she wrote in her diary. Snyder was about to marry the photographer Larry Fink, which put “a kind of structure in my life that I didn’t have,” she said of that time of “clarification.”

From her early “Flock paintings,” which explore the interior of a woman’s body, to later works that used feminist, heavy imagery, and collaged material, to explore her sexuality, or the “Bean Field” paintings, made while living surrounded by bean fields, each stage of art making reflects what Snyder was going through personally. They are autobiographical, but Snyder expresses this in abstract and metaphoric forms. This also indicates why she refuses to stay fixated on any single stylistic mode or idea. The paintings have to grow with her.

But change is not always easily accepted by the public. The popular “Stroke” paintings happened quickly, and by the mid-1970s Snyder wanted to go deeper, thicker. “There was a huge waiting list for those [Stroke] paintings…and I just stopped doing them. I could not do one more,” she said.

After those paintings, Snyder didn’t follow the trajectory of her contemporary male creators, who enjoyed comparable early careers. Today, particularly in Europe, many art professionals, including historians interviewed for this story, are just learning about her. Yet Snyder rightly feels her career brought her much joy, success, and allowed her to keep going as an artist, particularly — as she saw it — compared to her female contemporaries who were unable to exhibit or sell work. She was included in the 1973 and 1981 Whitney Biennials, the 1975 Corcoran Biennial, had a major solo and traveling exhibition at The Jewish Museum, New York in 2005, received a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship in 1983, a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in 1974, and a MacArthur Fellowship in 2007. The list of museums that own her work could fill an article of its own.

Joan Snyder, Painting at the Pond (2024) Photo: Adam Reich. © Joan Snyder. Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London · Paris · Salzburg · Seoul

Nevertheless, Snyder’s paintings were “a discovery for me and many of my colleagues, and the more we saw of her paintings from over the decades, the more surprised we were,” remembers Thaddaeus Ropac, speaking at his gallery. He also wondered why she “had received so little attention from Europe.”

Mark Godfrey, former contemporary art curator at Tate Modern, has a few ideas. “The lack of attention was partly to do with being a woman, and partly to do with the fact that she was a little bit out of step with what was considered for a while to be the most ambitious, formal abstraction of her generation,” which “mainly turned away from painting,” he said over the phone. Godfrey discovered Snyder’s work around 2010, when he read about it in an Artforum article. Thanks to his efforts, in 2020 the Tate acquired her piece Dark Stroke Hope (1971), where it hangs alongside Niki de Saint Phalle’s Tirage (1961).

The fact of being a woman, however, is a key puzzle piece, and a central subject of Snyder’s work. She also created the Women Artists Series in 1971, to show artwork by women at Douglass College’s library, and in 1976, she was a founding member of the Heresies Collective, which produced a journal about feminism, art, and politics.

Snyder said she wanted to express a more feminist language in her paintings, which she recognized are part of a certain “female sensibility.” In her 1992 essay, “It Wasn’t Neo to Us,” she describes how this was ignored by art history, and usurped by men, who dubbed it neo-expressionism:

“I believe that women artists pumped the blood back into the art movement in the 1970s and 1980s. At the height of the Pop and Minimal movements, we were making other art–art that was personal, autobiographical, expressionistic, narrative, and political–using words and photographs and as many other materials as we could get our hands on. This was called Feminist Art. This was what the art of the 1980s was finally about, appropriated by the most famous male artists of the decade. They called it neo-expressionist. It wasn’t neo to us.”

Joan Snyder:Body & Soul, installation view at Thaddaeus Ropac London, 2024.Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London ·Paris · Salzburg · Seoul.Photo:Aggie Cherrie.

For his part, Ropac has also been adding more women to its previously more male-dominated roster. “We really have begun to work with a number of important women artists, which we also sadly had not done sufficiently before,” he said. “We’ve learned our lesson and have been reminded to look more carefully, and I think we have.” Examples include Martha Jungwirth and Lisa Brice, as well as Megan Rooney, and Mandy El-Sayegh.

Today, Snyder still inspires a growing, almost cult-like following, including many artists who showed up at her last, sold-out show in New York at Canada gallery in January, which is co-representing her. “I can’t tell you the number of painters who made pilgrimages to her two shows at Canada,” said Canada gallery’s Sarah Braman. “They were coming to enjoy and experience the works, but also to study them.”

In the last few years, Snyder’s work has also heated up at auction. One 1973 painting cheekily titled The Stripper, of horizontal strips of paint and fabric, estimated for between $80,000 to $120,000, fetched $478,800 at Christie’s in November 2023. The works at Ropac are priced between $40,000 and $600,000. “I’m just grateful that she’s getting to feel the recognition while she’s alive,” said Snyder’s daughter, Molly Snyder-Fink, who is a filmmaker, artist, and writer.

“I haven’t absorbed it all yet,” Snyder said about the new attention since joining Ropac’s international program. “They must be making a mistake,” she half-jokingly told her wife, Maggie Cammer. Far from it. The only mistake was to overlook Snyder’s unmatched talent when it was right in front of us the whole time.