Art World

Joe Scanlan’s Collaborator on Controversial Whitney Piece Speaks

Ben Davis

Carolina Miranda, formerly the art critic for WNYC, may have moved to Los Angeles and taken her blog to the Los Angeles Times, but she’s still kicking up a storm about New York art news. A recent piece, “Art and Race at the Whitney: Rethinking the Donelle Woolford Debate,” takes on the still-simmering controversy over Joe Scanlan’s project in the recent Whitney Biennial, which exploded into the news when the art collective HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN? cited offense over Scanlan’s work as one reason for their withdrawal from the Biennial (though they also have spoken about much wider concerns about discrimination within the art world).

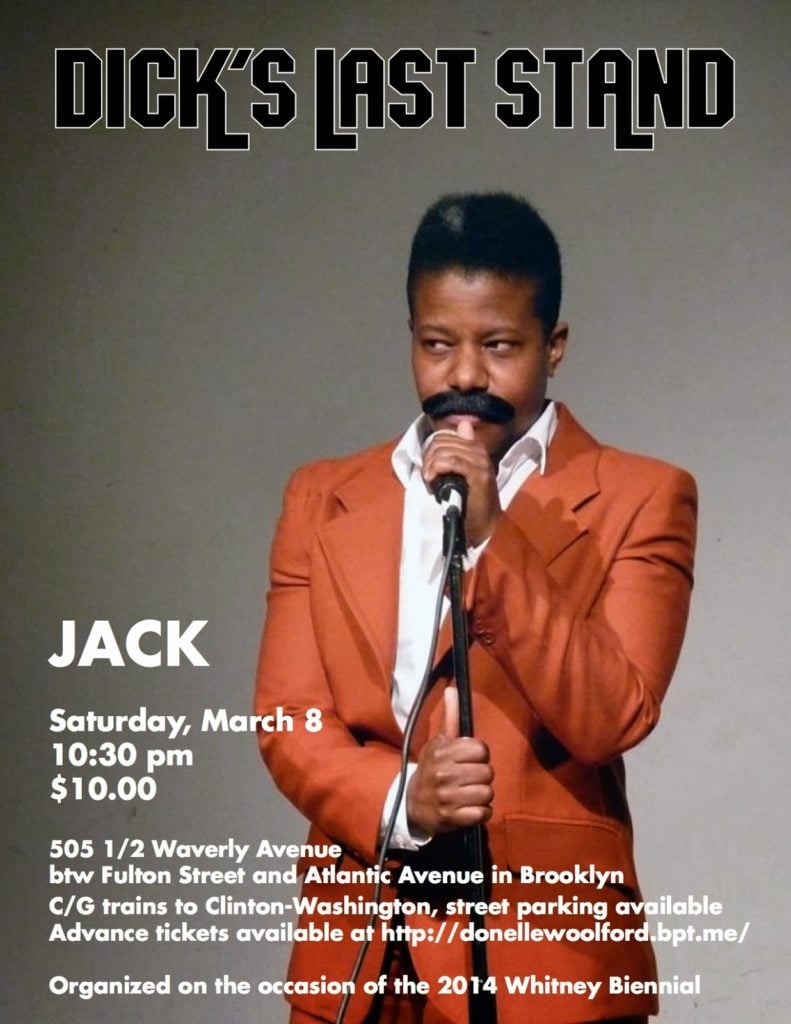

The controversy in a nutshell: Scanlan has a long-running body of work made in the persona of an African-American artist, for which he actually hires African-American actresses to play the part of the fictional “Donelle Woolford” character, creating both paintings and performance art (including a performance that has her re-perform a Richard Pryor routine). The act of a white artist appropriating an African-American identity has drawn extensive fire as racially insensitive or even akin to minstrelsy. Miranda tracks down Jenn Kidwell, one of the actors Scanlan has collaborated with on the Woolford initiative, to get her take on the matter.

The whole article, which also has some telling quotes from Biennial co-curator Michelle Grabner, is worth reading, but since it stresses that adding Kidwell’s voice to the puzzle is key, here are a few of the actor’s most significant quotes:

Kidwell was also skeptical of the project when Scanlan recruited her: “He explained the project and you know what I said to him? I said, ‘No, I don’t want to be involved in your post-colonial [trash].’ But then we talked further and discussed how important identity is to the way we receive art. It then became a personal challenge to me, investigating that question of why that is so important and how it changes an audience’s relationship to an artwork.”

Kidwell now considers herself a co-author of the work: “I had someone say, ‘He could fire you,’ and I say, ‘I could quit.’ Other people have said, ‘No, you are not a collaborator!’ And I’m like, ‘How are you telling me that I’m not doing what I’m saying I’m doing?’”

For Kidwell, the piece is about issues of power and discrimination: “People have said, ‘Joe Scanlan wouldn’t be in the Whitney Biennial if Donelle Woolford wasn’t black.’ Well, Donelle Woolford wouldn’t be in the Whitney Biennial if Scanlan wasn’t white. The whole thing, to some degree—it’s a successful exposure of that fraught historical relationship, of that exploitation.”

And also: “I could be doing the Richard Pryor piece myself and nobody would care. I do a lot of stuff that nobody cares about. The piece is beyond successful in that it shines a light on who gets the attention, who gets listened to.”

Kidwell feels that she has not been heard in the current controversy: “I’ve felt un-addressed. There is a black artist present in this piece. Why am I erased from it? Why do I continue to be erased from it?”