On View

In 1963, a Group of Black Photographers in Harlem Decided to Build Their Own Art Ecosystem. A New Whitney Show Tells Their Story

The show is on view now at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

The show is on view now at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Taylor Dafoe

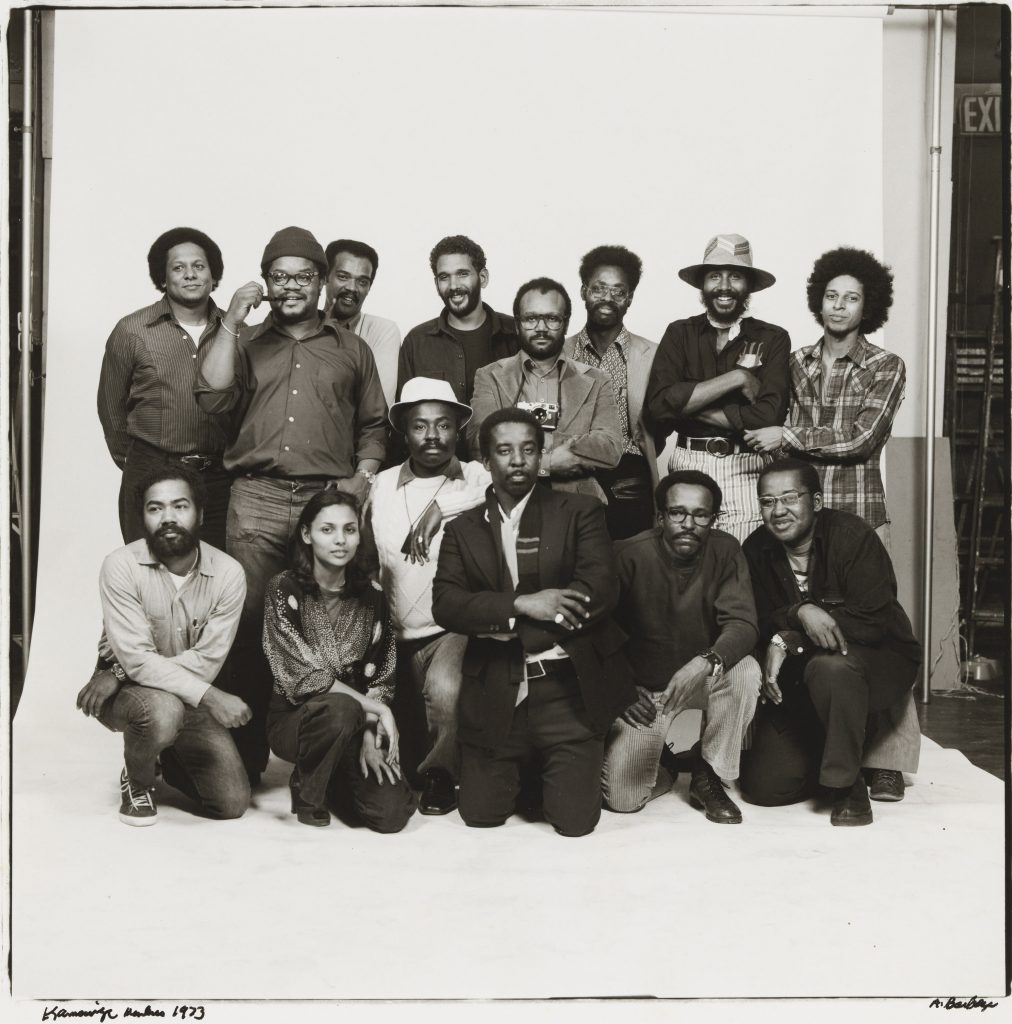

Perhaps the most famous photograph to emerge from the Kamoinge collective, founded by an enterprising group of Black artists in New York nearly 60 years ago, is a picture of the Kamoinge collective: 14 early members of the seminal group crowded before a blank backdrop, spilling beyond its edges in poses alternatively sanguine and serious.

It’s fitting. The group, created in Harlem as a space for photographers to commune and collaborate, has always been more than the sum of its parts. The mentality is baked right into the name, which is borrowed from the Kikuyu word meaning “a group of people acting together.”

“To me, this photograph captures the energy and spirit of the group as a whole, but also gives you a glimpse into their individual personalities and styles,” says curator Carrie Springer, who helped organize an exhibition about the work and legacy of the Kamoinge Workshop on view at the Whitney Museum now.

The show, titled “Working Together,” includes around 140 pictures by the group’s members taken throughout the 1960s and ’70s as they staked a claim for photography in the flowering Black Arts Movement.

Springer, who adapted the exhibition from a previous version organized earlier this year by Sarah Eckhardt at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA), says the photos constitute the workshop’s primary legacy. But not far beyond are their accomplishments behind the camera: “their self-organizing, long-standing commitment to their communities, and centering of Black experiences and audiences in their art.”

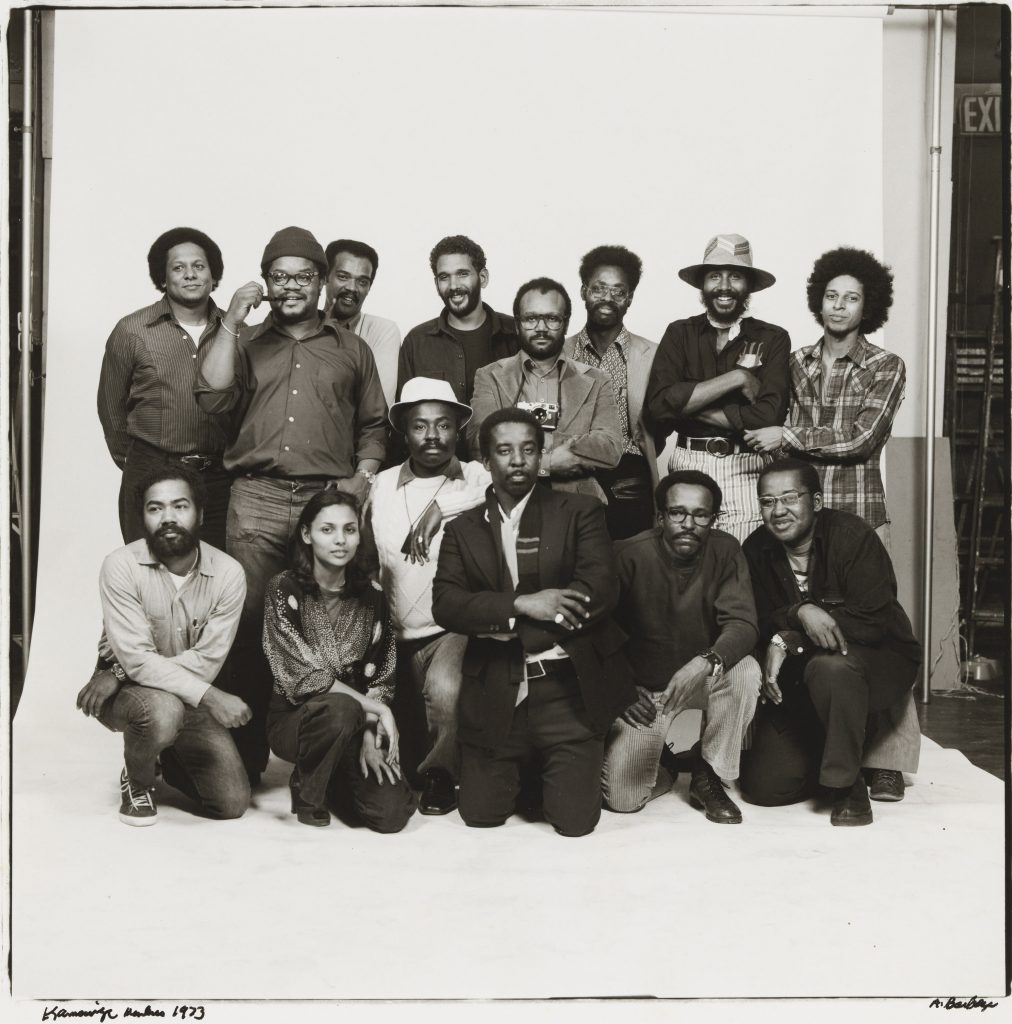

Ming Smith, America seen through Stars and Stripes, New York City, New York (ca. 1976). Courtesy of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. © Ming Smith.

Kamoinge was fused from two groups of Black photographers at a joint meeting in 1963. Among the inaugural members were Albert Fennar, Herb Randall, Shawn Walker, and Louis Draper, all working photographers who, as Draper himself put it, were “well acquainted with the barriers which prevented Black photographers a voice within the usual communication.”

The goal was to produce their own portfolios and open a gallery outside the mainstream as an outlet for their work. But despite the obstacles of operating outside the established system, the group’s outlook was optimistic.

“With all the untapped talent amidst [the group’s members], there was no reason why it should not be developed and expressed,” Draper recalled. “Thus it is valid to state that the Kamoinge Workshop, while operating within an arena of negation, was primarily forged in an atmosphere of hope and not despair.”

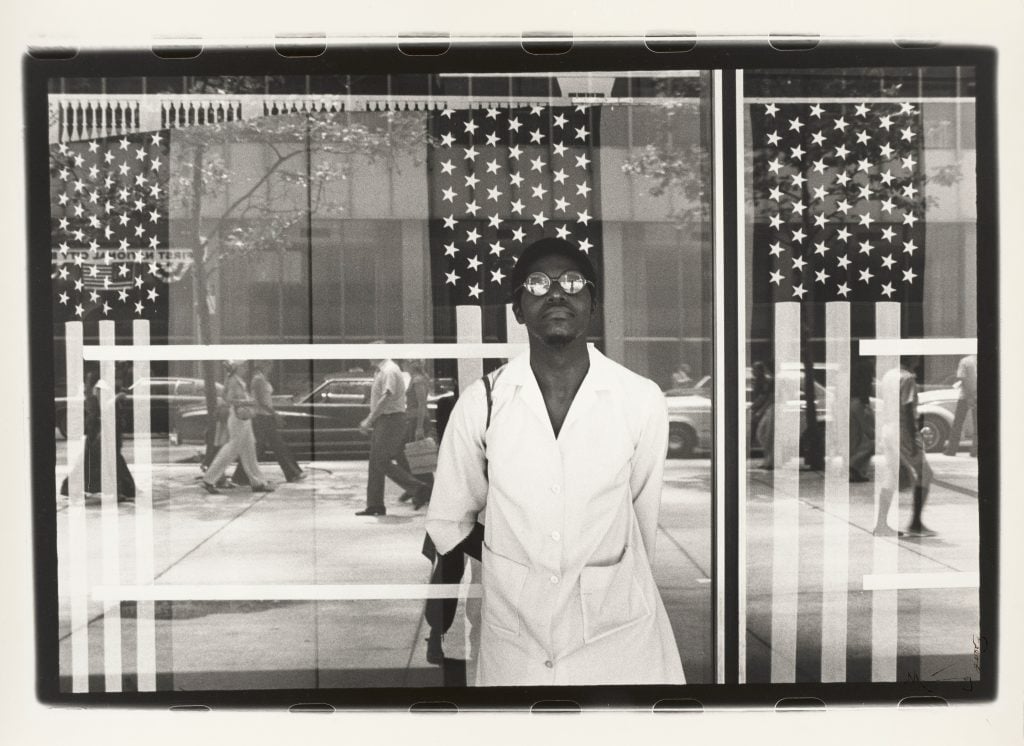

Shawn Walker, Easter Sunday, Harlem (125th Street) (1972). Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of Art. © Shawn Walker.

Ambassador, historiographer, teacher, father figure: Draper was especially instrumental in shaping the workshop’s vision as it evolved. He brought in Langston Hughes, who lived in Draper’s apartment building, as an advisor. Hughes, in turn, introduced the group to pioneering photographer Roy DeCarava, who became Kamoinge’s first director. Draper also brought numerous artists into the fold, including Ray Francis, Daniel Dawson, and Ming Smith.

It was through Draper’s work that Eckhardt was introduced to the workshop 50 years after it was formed. In 2012, Draper’s sister brought a box of his works to the VMFA hoping the institution would be interested in acquiring his rich archive. (The VMFA was and did.)

“She opened for me this box of photographs and they were just stunning, amazing images,” Eckhardt says. “I immediately ran down the hall and got the chief curator.”

That initial meeting led Eckhardt on an eight-year research path through the history of the workshop, culminating with a scholarly publication published by the VMFA and the capstone exhibition that opened there in February.

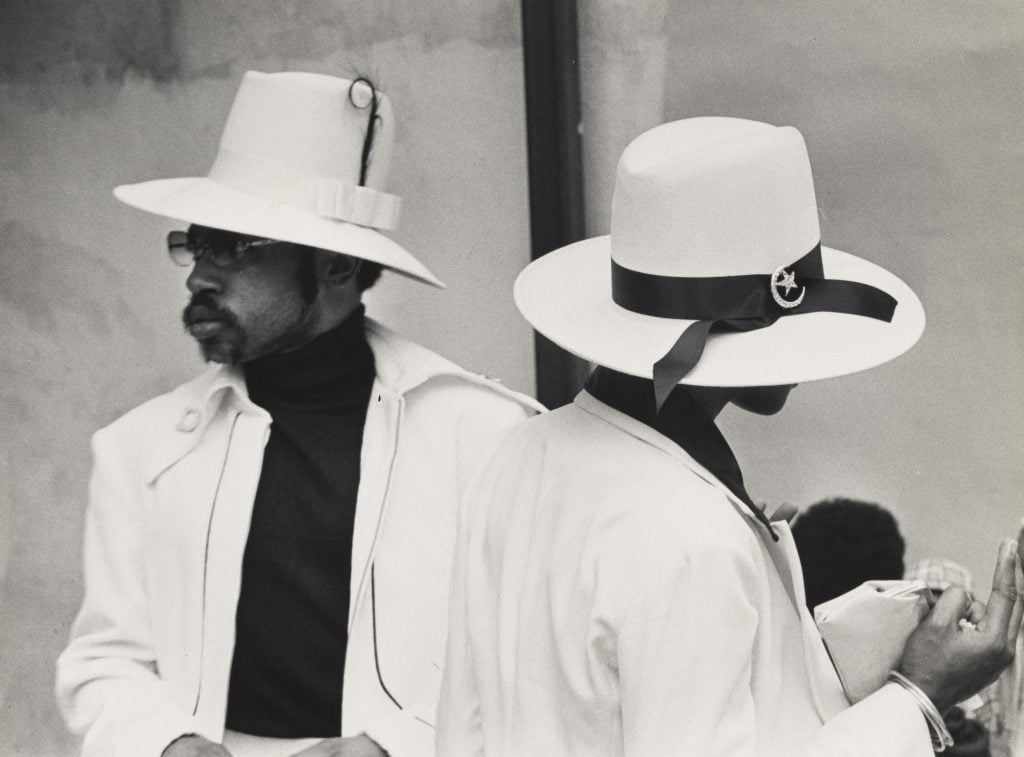

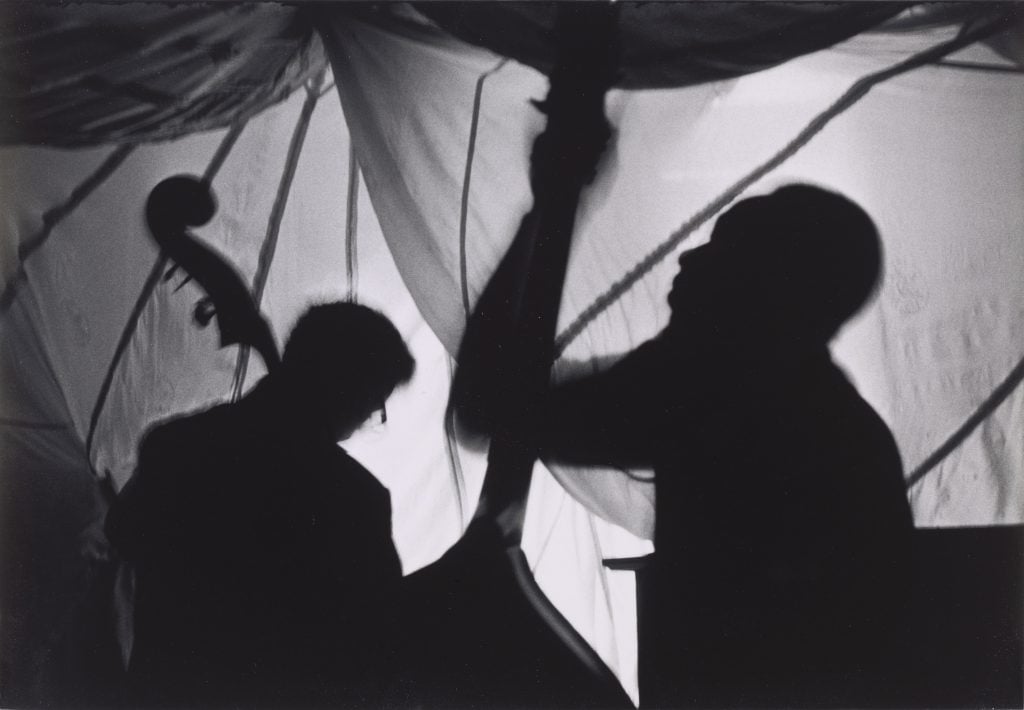

Beuford Smith, Two Bass Hit, Lower East Side (1972).Courtesy of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. © Beuford Smith/Césaire.

Only recently, Eckhardt says, did she fully grasp the scope of the group’s influence on both New York communities and Black photographers around the world.

“What I came to understand was that they were not just teaching technical skills, photography skills,” she says. “It really was about teaching the mission statement of Kamoinge, which was truth in representation and thinking about how your community is being portrayed and who is portraying it.”

“Working Together: The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop” is on view through March 28, 2021, at the Whitney Museum of American Art.