Art & Exhibitions

50 Years Ago, Romare Bearden and His Colleagues Founded a New York Gallery for Artists of Color. A New Show Celebrates Its Legacy

The show explores the gallery's ties to the Art Students League of New York.

The show explores the gallery's ties to the Art Students League of New York.

Sarah Cascone

In 1969, tired of the lack of exhibition opportunities for Black artists, Romare Bearden, Ernest Crichlow, and Norman Lewis took matters into their own hands and opened Cinque Gallery, a nonprofit exhibition space on Astor Place in New York’s East Village.

Cinque—named for Joseph Cinque, who led the 1839 revolt on the Amistad slave ship after being kidnapped in Sierra Leone—quickly became a thriving community of young and mid-career artists.

Over its 35-year existence at various spaces across the city, the organization showcased the work of some 450 artists of color, including Emma Amos, Dawoud Bey, Sam Gilliam, and Whitfield Lovell—all of whom are featured in the first-ever exhibition celebrating the legacy of Cinque Gallery at the Art Students League of New York.

“This is unprecedented,” Susan Stedman, the exhibition’s guest curator, told Artnet News.

An art administrator and close friend of the gallery’s founders, she was closely associated with Cinque throughout its history, and since 2017 has been working on an oral history of the gallery, building on the records held by the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.

The show at the league grew out of a 2019 event at the Harlem School of the Arts organized by the Romare Bearden Foundation to mark the gallery’s 50th anniversary. Stedman was a panelist, along with Nanette Carter, who became Cinque’s first artist in residence.

Norman Lewis and students at the Art Students League of New York. Photo courtesy of the Art Students League of New York.

Among those in attendance that night was Genevieve Martin, then the league’s director of external affairs. The discussion caught her attention because many Cinque Gallery artists studied, and, in some cases, taught, at the league. At the end of the night, Martin approached Stedman and Carter and proposed putting on a show about Cinque and its ties to the Art Students League.

The first African American teacher at the league was Charles Alston, who joined the faculty in 1950 and later showed at Cinque. The school also employed other artists associated with Cinque, inlcuding Richard Mayhew, Jacob Lawrence, Al Loving, and Hughie Lee-Smith, as well as all three gallery founders. Bearden had also previously taken classes at the Art Students League, as did many Cinque artists including Elizabeth Catlett, Ed Clark, Mavis Pusey, and Charles White.

Highlighting those connections is a thread that runs through the show, but Stedman did not limit herself to league artists.

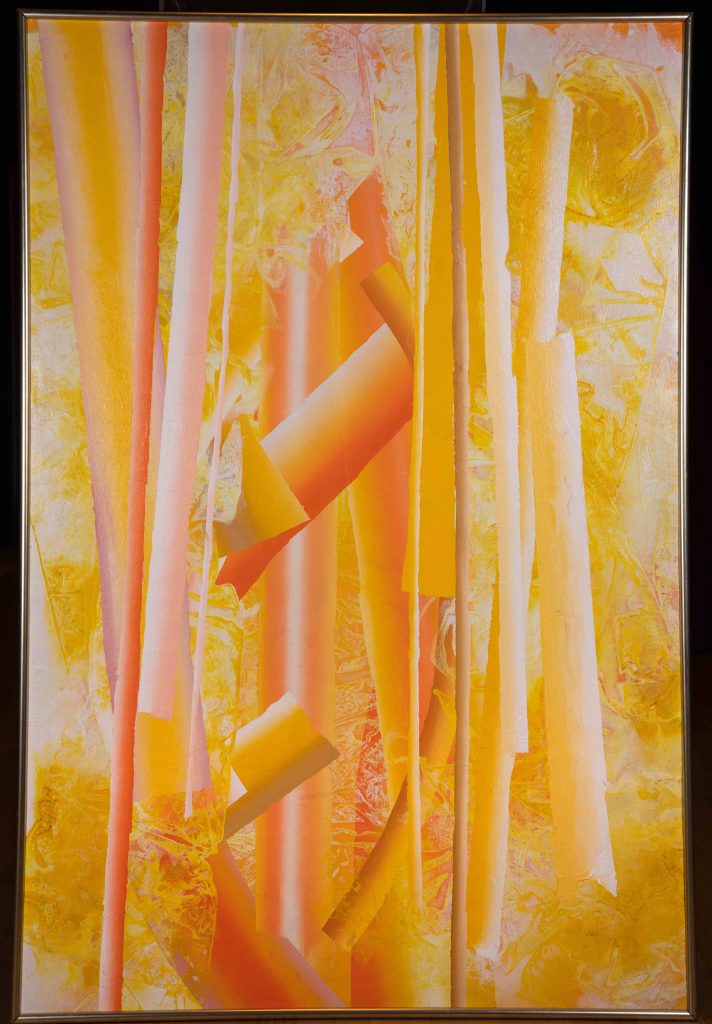

“I also wanted to seek out some of the elders, such Otto Neals, Frank Wimberley, and Bill Hutson, who are still working today, as well as women like Cynthia Hawkins, Debra Priestly, and Robin Holder,” she said. “Bill Hutson makes a point of saying he has only had two solo shows in New York—both at Cinque. His work should be more widely known. I wanted to have a mix of those who are still under-recognized with those who are now well known.”

Bill Hutson, Ten Series #10 (1991). Courtesy of the Art Students League of New York.

“We want people to know about this space and how Cinque was instrumental in a lot of artists’ careers,” Carter, the guest programming curator for the show, told Artnet News.

Carter had first visited Cinque in the early 1980s after hearing about it from other African American artists. She was immediately blown away. “I thought, ‘wow, this is fantastic,'” Carter said. “They exhibited artists of color, including Asian artists and Hispanic artists, at a time when there were very few places showing our work. Artists from near and far would try and be selected.”

Her residency took place when she was still fresh out of grad school, offering her a stipend that made it possible to focus full-time on her studio practice. But Cinque afforded similar opportunities to artists who had been pursuing their career for much longer.

“Cinque was supposed to be a gallery for emerging artists, but back in the 1960s and ’70s, you could be 50 or 60 and still be ’emerging,'” Carter said. “Many of these African American artists had been working all their lives but had not exhibited.”

And although Cinque provided an invaluable platform for artists of color, it still took years before many of them were widely recognized for their work.

Romare Bearden, Culture: Hartford Mural (1980). Courtesy of the Art Students League of New York.

“I use the term cultural apartheid to describe the extent to which mainstream institutions and most dealers resisted any attention to these artists,” Stedman said. “Cinque didn’t have a dramatic or visible impact on the world of museums and galleries at the time.”

The exhibition is largely drawn from the league’s collection, with loans from various private collections.

“I deliberately did not include museums among the lenders, because museums have been overlooking and ignoring the work of Black Americans too long,” Stedman said. “This neglect continued for years and years and years, and it’s still a problem. I wanted to demonstrate that there are these other significant sources—Black collectors specifically—that are and were supportive of African American artists.”

“I’m hoping that on the heels of this show, people will think about doing further research about Cinque,” Carter said. “Someone could put together a mammoth museum show.”

See more works from the exhibition below.

Norman Lewis, Untitled (1976). Courtesy of the Art Students League of New York.

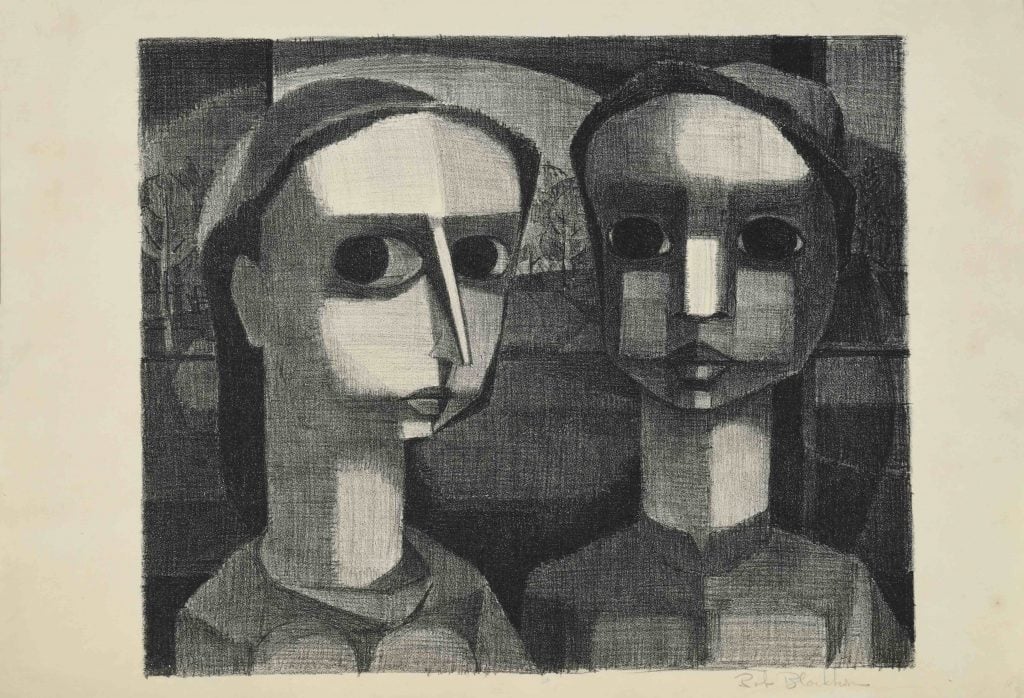

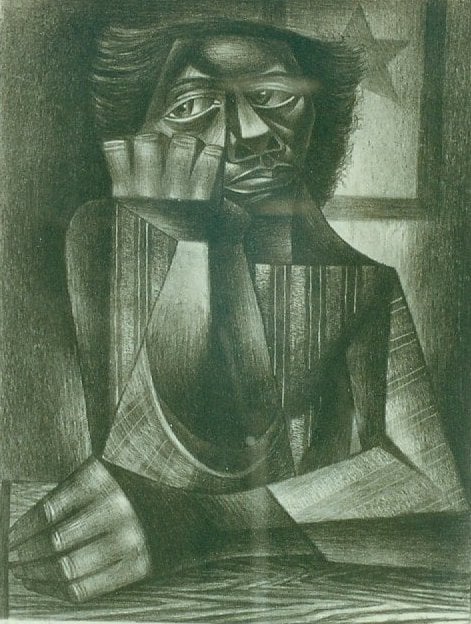

Robert Blackburn, Youth (1944). Courtesy of the Art Students League of New York.

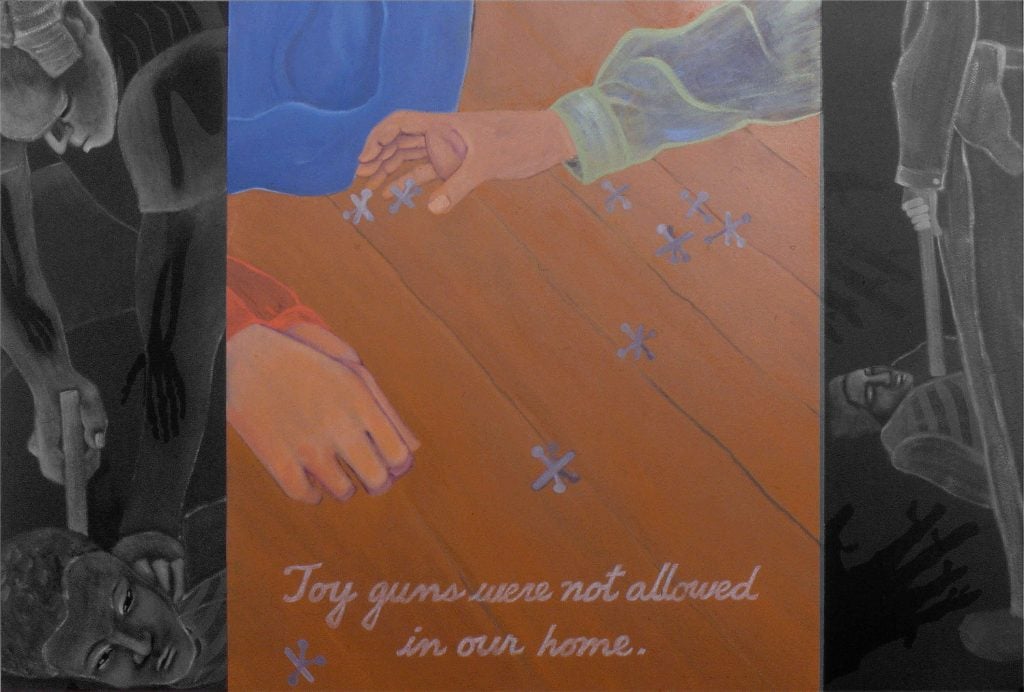

Robin Holder, No Toy Guns (1998). Courtesy of the Art Students League of New York.

Nanette Carter, Cantilevered #39. Courtesy of the Art Students League of New York.

Otto Neals, Young General Moses (1984). Courtesy of the Art Students League of New York.

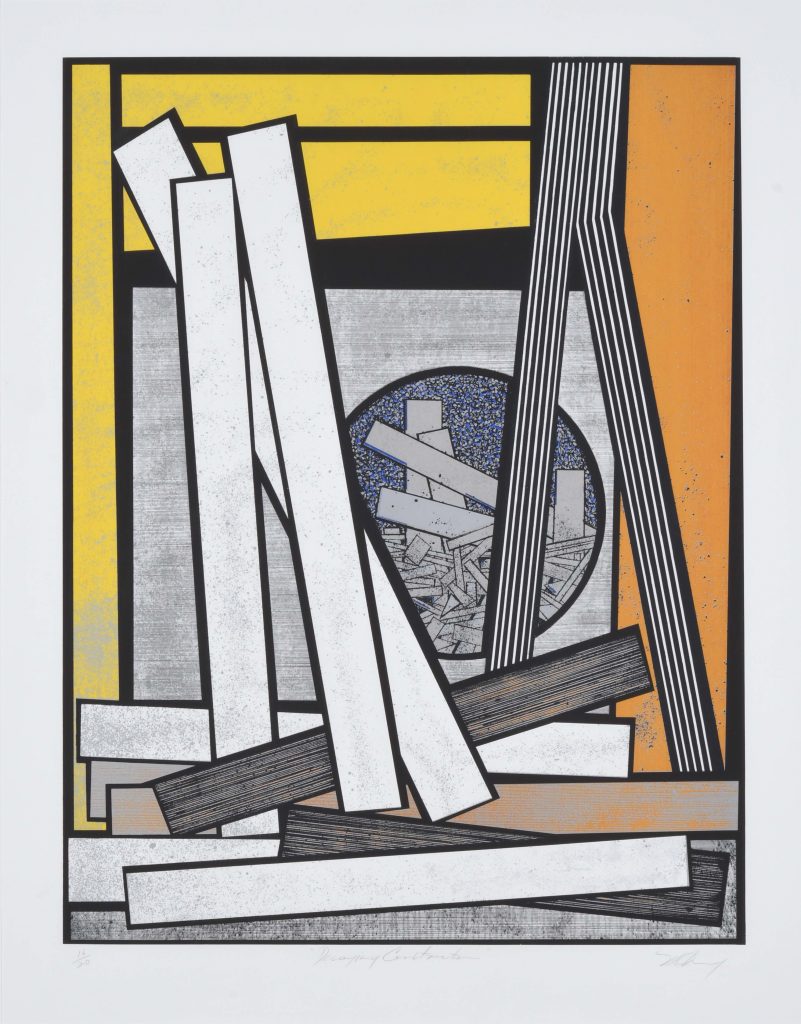

Mavis Pusey, Decaying Construction. Courtesy of the Art Students League of New York.

Charles Alston, Red, White, and Black (ca. 1960). Courtesy of the Art Students League of New York.

Charles White, Mother (Awaiting His Return), 1945. Courtesy of the Art Students League of New York.

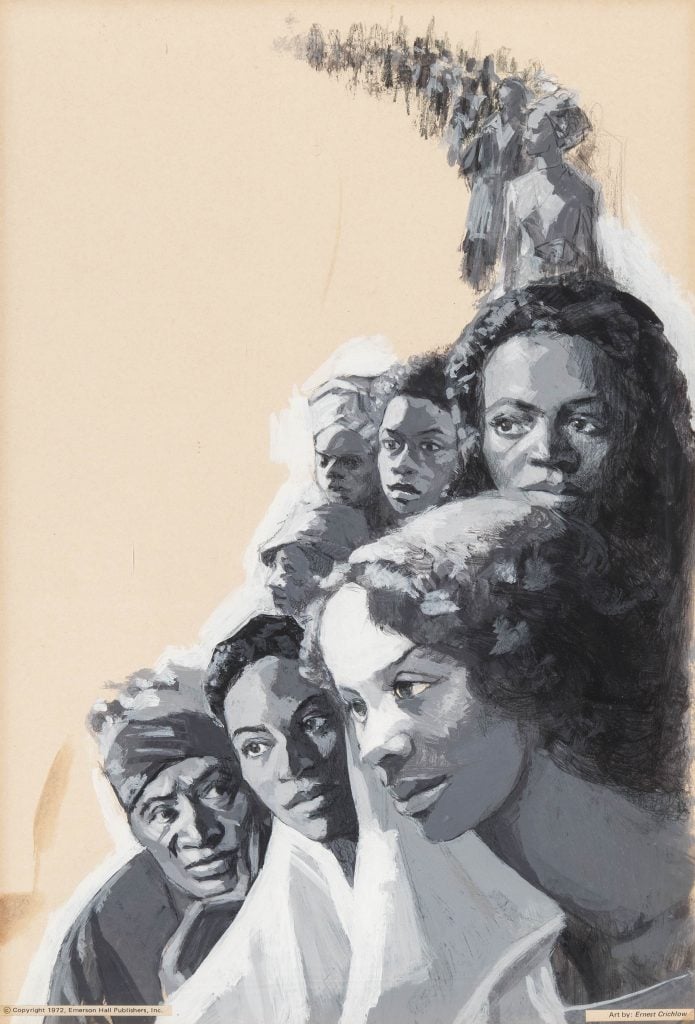

Ernest Crichlow, The Strengths of Black Families (ca. 1970–73). Courtesy of the Art Students League of New York.

“Creating Community: Cinque Gallery Artists” will be on view at the Art Students League of New York, 215 West 57th Street, New York, May 3–July 4, 2021.