Museum schedule changes rarely incite impassioned editorials and mobilize opposition from dozens of the world’s most eminent living artists. But the announcement, two weeks ago, that the opening of a touring retrospective of the work of modernist painter Philip Guston would be delayed until 2024 hit a nerve.

The museums behind the show—the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Tate Modern in London; and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston—said they were putting it off “until a time at which we think that the powerful message of social and racial justice that is at the center of Philip Guston’s work can be more clearly interpreted.”

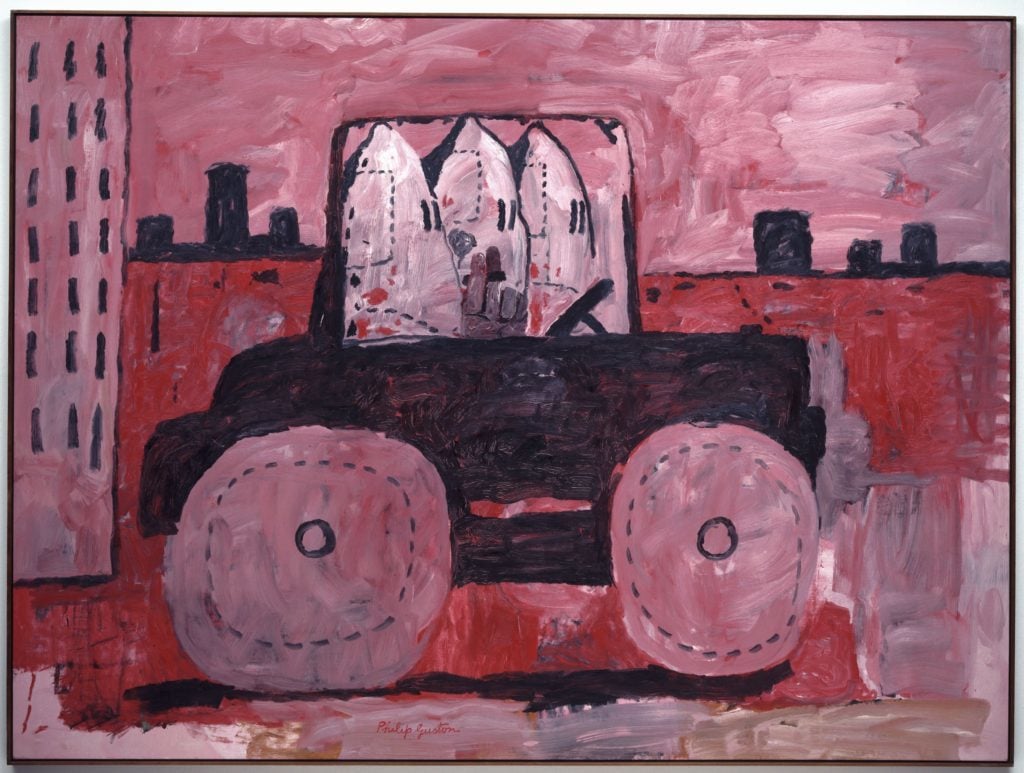

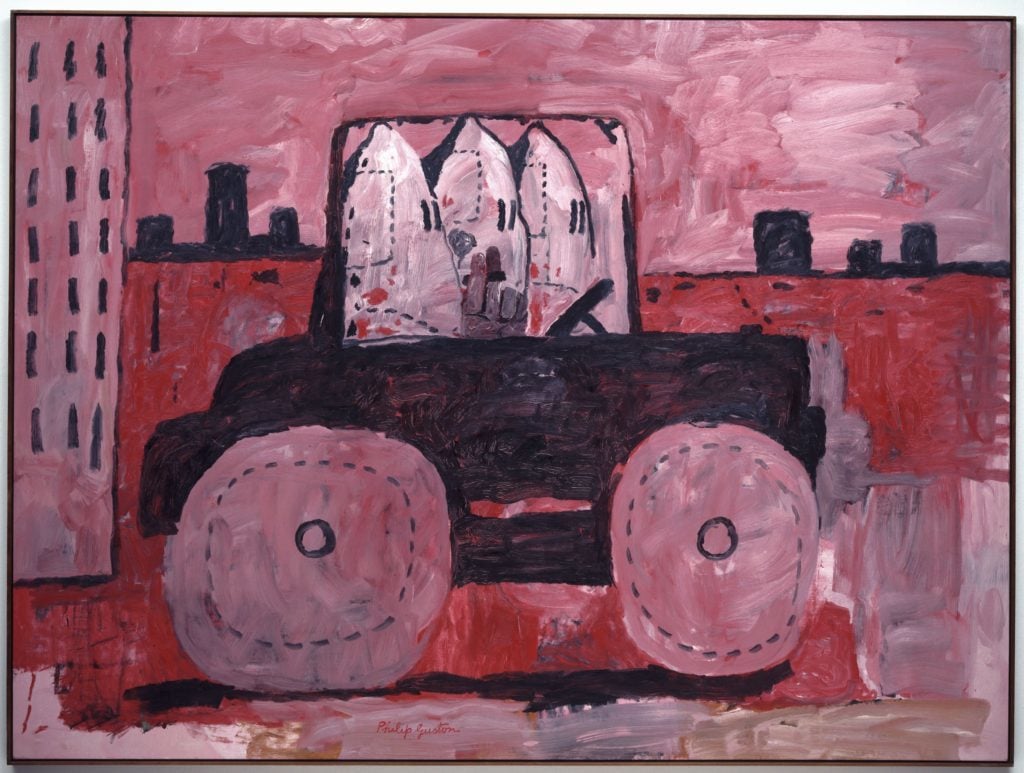

The images at the center of the decision are 25 drawings and paintings that evoke the Ku Klux Klan, showing hooded figures as they go about their days riding in cars, working at easeles, smoking. As Guston’s daughter, Musa Mayer, put it in a statement opposing the delay, these images “unveil white culpability, our shared role in allowing the racist terror that [Guston] had witnessed since boyhood, when the Klan marched openly by the thousands in the streets of Los Angeles.”

Nearly 100 artists, writers, and scholars penned an open letter admonishing the museums for the decision. But Kaywin Feldman, the director of the National Gallery of Art, is standing firm. Her institution would have been the show’s first American stop in June. (Pre-lockdown, it was originally due to open there this past summer.)

Feldman, who joined the National Gallery in 2019 from the Minneapolis Museum of Art, first spoke out about her decision on the Hyperallergic podcast. We followed up with her to find out more about one often overlooked constituency that opposed the show, what she’s learned from the process, and why she feels the National Gallery of Art—and museums writ large—can no longer proceed with business as usual.

Philip Guston, The Studio (1969). ©The Estate of Philip Guston. Private Collection. Photo Genevieve Hanson.

I want to start by talking a bit about chronology. In mid-June, following the killing of George Floyd, curators worked together to revise and broaden the wall panels and educational materials for the Guston show. At what point, as that process was underway, did you all conclude that the show was going to require a more fundamental rethinking and would not be ready for prime time next summer?

Ever since the killing of George Floyd, staff members were voicing increased concerns about proceeding. Through the course of July and August, we had increased conversations, both in the building and with external voices, about how we should react. I should also point out that the National Gallery, like so many museums in America, received an anonymous petition over the summer demanding change at the gallery. So, it’s a heightened moment for museums—and I think it’s just extraordinary that art critics haven’t noticed the extreme pressure that museums received both internally and externally to change our practices and to be more inclusive and equitable. And, as our critics point out, that doesn’t just mean issuing statements of solidarity, it means actually changing things and making difficult decisions, which is exactly what Guston was. We decided that, institutionally, we weren’t quite ready to do the exhibition justice.

Philip Guston, Scared Stiff (1970). The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy of the estate and Hauser & Wirth.

There was a strong reaction to the four-year delay. What do you feel you could do in that time frame that you couldn’t do in the nine or 10 months before the show was scheduled to open?

First of all, while we said four years, we’re actually now all trying to get our exhibition schedules together. It was sort of a random date to get us well past COVID and to the point where we all had some flexibility to reschedule. There’s no real magic to the four years. Now, it’s looking like it’ll be less time.

Something we can’t do now is all sit in a room together and have difficult conversations. You cannot do this work by Zoom. It really requires the ability to come together in person respectfully and have the conversation. So part of it is getting on the other side of the pandemic. We are also in the midst of lots of changes here at the gallery, including our first ever chief diversity, inclusion, and belonging officer, Mikka Gee Conway, who started last Monday. I hired Mikka because she started her career as a curator, and then got her law degree, and has most recently been a lawyer at the Getty and has devoted her career to diversity and inclusion. She has a particular skill set that can help us be thoughtful and inclusive in our programming, our exhibition and curatorial work, as well as our internal work. And then we are also just about to start interviews for a new curator in the Modern and contemporary department with a focus on African American art and art of the African Diaspora. I’ve been making quite a few hires. I inherited an all-white executive team and our executive team is now 30 percent BIPOC. So there are changes in the works.

On the Hyperallergic podcast, you mentioned you might bring in a curator of color to contribute to the show, which currently has an all-white team. But obviously that is complicated when a version of the show is already almost complete. You also said, “because Guston appropriated images of Black trauma, the show needs to be about more than Guston.” What do you mean by that, and what might that look like?

I have to be honest that I don’t actually know at this point, and I respect the work of the curators, so I’m not going to tell them what the show needs to be. It will be a show focused on Philip Guston, but there needs to be context around his work showing the hooded figures. That includes doing a lot of listening, because there are a lot of perspectives on the work—there isn’t one single interpretation of it. The response [from critics] has been, “Just explain it to people.” Absolutely, Guston has modern relevance, he had anti-racist views, and he used his Klan imagery subversively to examine racism and evil. But we also need to honor the response of viewers and recognize that those are triggering images. Regardless of the artist’s intentions, the symbol of the Klansman is a symbol of racial terrorism that has been enacted on the bodies and minds of Black and brown people from our country’s founding. The argument of just, tell them what to think—it doesn’t work when it comes to Klan imagery.

Philip Guston, City Limits (1969). Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, gift of Musa Guston, ©the Estate of Philip Guston and the Museum of Modern Art, licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY.

When you say additional context, what are you thinking of? Without prescribing what the curators should do, can you give an example of an exhibition where you feel like that kind of context was provided adequately?

I think it’s additional information about Guston in his time period—it’s a different world than when he made the works in the 1970s. It’s a different world than when [National Gallery curator] Harry Cooper started the show in 2015. So I think it’s context around the images and also additional voices speaking to how the images might be seen.

You asked for a specific example. It’s not contemporary, but I think a great example is the ancient Nubia show [“Ancient Nubia Now”] that the MFA Boston did about a year ago. They did an excellent job of honoring beautiful and important works of art in their collection and allowing the art to speak for itself. They also examined the racism of the original excavators and curator who uncovered the material, who said the most awful things and actually assumed the objects had to have been made by white Egyptians, not Black Africans, because they couldn’t possibly have made something so beautiful. Boston was completely transparent and even quoted him in some areas. And they brought in voices of local community members to whom the work was really powerful and important. I think it’s a great example of being able to show an exhibition from many sides and being transparent about it.

You said you’ve had conversations both within the museum and also with people outside the institution. Who did you go to outside the museum, and what sort of feedback did you get?

Well, I think it’s important to say that there are multiple perspectives and I absolutely recognize that there are certainly African American artists who feel the show should continue in its original time slot, and there are others who think it should not even happen at all, and then others who point out all the changes that need to happen in the institution [before we could responsibly do the show]. I don’t in any way want to say there’s one voice. I don’t speak for African American audiences—I am a white woman of privilege, which I acknowledge. But I internalized the conversations and I also spoke to my colleagues, to other museum directors who grappled with similar issues, which is really everybody in the field. And I’m one director—the other three [directors at museums on the show’s tour] had the exact same journeys. Our situations are different, but we all came to the same conclusion.

A museum guard walks past a painting by Robert Motherwell, Reconciliation Elegy, at the National Gallery of Art East Building on the National Mall in Washington, DC. Photo by Robert Alexander/Getty Images.

One group of stakeholders that I heard had come forward with some issues about the show were the guards. I wanted to ask you about that, since I think it’s a constituency that we don’t always consider is on the front lines of interpretation for audiences.

Thank you for bringing up the guards. Actually, you know, if you Google the National Gallery, you’ll find some pretty harsh stories in the past about our relationships with the guards. Since I arrived, I have invested a lot of time with our guards, who I have come to adore. It’s important to look at the institution: 98 percent of our curatorial department—that includes everybody, from assistants to senior curators—is white. Which means that only two percent of curatorial is BIPOC. Security [staff] is 83 percent BIPOC. So, it’s really important that our team spend time listening to our guards because they have the expertise of knowing our audience. They spend all day in our galleries. Going forward, we will be spending more time hearing from our guards on this particular exhibition and getting their thoughts about how we might display and interpret it.

Have the guards had any direct conversations with either you or the show’s curators about the show?

We’ve had conversations in the past about Guston, and in this particular instance, we’ve talked to a handful. I was asked not to show them the images because they are so disturbing at this moment in time.

Show them in conversations leading up to the show, you mean?

Yeah. So, for example, someone suggested that we hang one of the hooded figures on the wall and bring the guards in to have a conversation. Needless to say, it’s much harder when most of our staff is still teleworking and we can’t gather everyone in a single room anymore because of capacity restrictions. And then I think the other point is, as you know, this is just a heightened moment of great emotion and sensitivity and panic. It’s not a good time for rational discussion.

Alexander Calder’s untitled aluminum and steel mobile hangs from the ceiling at the National Gallery of Art East Building on the National Mall in Washington, DC. (Photo by Robert Alexander/Getty Images)

I appreciate you pointing out the staff numbers, because another thing I had been thinking about is the museum’s own record of showing work by Black artists. In a study we did with In Other Words a few years ago, we found that between 2008 and 2018, just 1.7 percent of the NGA’s acquisitions were of work by African American artists, and two percent of its exhibitions featured majority or exclusively African American artists. How did the museum’s own record, and the fact that it has lagged behind in terms of engaging with the work of Black artists, play into this decision?

I think we all here know that we have lots of work to do to change the institution. I’m the first one who always reminds people that by 2043, it’s projected that America will be majority people of color. As you just pointed out, our collection does not reflect that. Ninety-eight percent of the works in the National Gallery’s collection are by white artists. Our exhibition history—the data is a little hard to pull out, but it looks like we’ve done 93 large monographic exhibitions since 1999 and of those 93, only three have been BIPOC artists. The rest are all white artists. We don’t have a strong record and we’re committed to changing that.

Recently, because we’re doing a strategic plan, we did a survey of our staff to identify our most closely held values. An extraordinary number—two-thirds of our staff—answered the survey. The number one value that they determined as most important for the National Gallery was diversity, equity, and inclusion. So we have to get that right.

One of the things that’s so tricky is that there are the ethics of doing a show like this without properly engaging the Black community and other people of color. But on the other hand, there’s the point, which I’m sure you’ve read many times by now, that the show is important because it’s about white complicity, and it’s important for white people to be involved in dismantling racism since we are the ones who benefit from it. What would you say to people who say that conversation about whiteness is important to have right now, and feel as if the museum is simply uncomfortable doing so?

I would stress that I’m absolutely committed to doing this exhibition and I believe in Philip Guston. I’m not sure that I would argue that the public needs a white artist to explain racism to them right now. That, combined with the meager track record that the National Gallery has of showing and engaging artists of color, makes it difficult that one of our first major exhibitions about racism is from a white perspective.

I’m curious how this experience will inform the way the National Gallery plans to approach shows that deal with race in the future. What sort of structural changes or implementation of advisory committees are you considering? Obviously, it’s a case-by-case situation based on the show. But in the wake of the Dana Schutz controversy, for example, I spoke to a lot of museum directors who changed the way they prepare for shows, who now talk to community members earlier in the process. How might you use this experience to create a blueprint to approach these things differently in the future?

I should note that this show was not just conceived, but really assembled, before my arrival. And I do see it changing practice for some of our exhibitions in the future. Not all exhibitions dictate the same process, but I’m a big believer in advisory panels—sometimes it’s more of a scholarly-scientific advisory panel, other times it’s a community advisory panel or an artist advisory panel. There’s lots of ways to engage other perspectives.

To start early is key. You don’t want to do it a week before the show opens and find out that some of your assumptions were wrong. From the very beginning, it means establishing trust with those potential audiences and being able to have difficult conversations where sometimes it’s about compromise. You’ve got to, first and foremost, be humble. I’ve had so much criticism in my career about some of my assumptions and some of the things I say, my thinking process as, again, a privileged white person. And when I hear them, it stings. I’ve learned to swallow and think very carefully and process. And I always learn something. I’ve become better because I listen to it, but it’s not easy.

Philip Guston, Painting, Smoking, Eating (1973). Courtesy of the Stedelijk Museum/©the estate of Philip Guston.

What sort of constituents would you reach out to in advance and what might that process look like in this new paradigm?

There’s no one size fits all. But for Guston, for example, I could see engaging the artists who have signed the open letter [opposing the postponement] to help us think it through. Absolutely listening to the community, because every museum has its own community and sensibilities. Talk to the guards, hear more broadly from our staff members.

I’ve been struck that most of the critics who have been writing about the decision haven’t even bothered to call us to confirm their assumptions about it. So it’s completely indicative of what I think is wrong with our field. It’s too much telling and not enough listening.

What do you think the most flawed assumptions have been?

First of all, to say that we have cancelled the show, when we have so firmly said we have postponed it and will soon come out with new dates. I think it’s flawed to say that museums have to make audiences understand our scholarly interpretation of the work—that insistence is embodied in the basic assumption that museums always know what’s best for the public.

You recently repeated a comment from one of your staff members who said that we project our biggest fears about the direction of culture onto the decision to postpone the Guston show. Specifically, I think the fear is that we are moving into an era of self-censorship, and that works that are challenging aren’t going to be engaged with. If the concerns that guided the Guston delay become more widely adopted, how do you think scholarship and art history will change?

Scholarship has always been the bedrock of what we do and it always will be. We now live in such an “either/or” culture. People assume if you are for one thing, you are against another. I see it very much as different ways of approaching one challenge or opportunity. I think scholarship is stronger and informed by listening to other people. It’s not either/or.

Minneapolis [the Minneapolis Institute of Art, where Feldman was director from 2008 to 2019] does tours for veterans who struggle with PTSD, and I followed the group one day. I learned so much about the collection by hearing about it from them—particularly when we were looking at images of soldiers and war throughout the collection, across cultures and time periods. Seeing the works through their eyes helped me see them completely differently as someone who has never served in the military. It was a firsthand lesson for me of the benefits of listening to other people. We don’t have all the answers. And we have to have the humility to know that.