People

Artist Kehinde Wiley’s Latest Paintings Are a Progressive Riposte to Paul Gauguin’s Primitivist Portraits of Tahitians

We spoke to the artist about his travels to Tahiti and the residency program he will be opening next month in Senegal.

We spoke to the artist about his travels to Tahiti and the residency program he will be opening next month in Senegal.

Naomi Rea

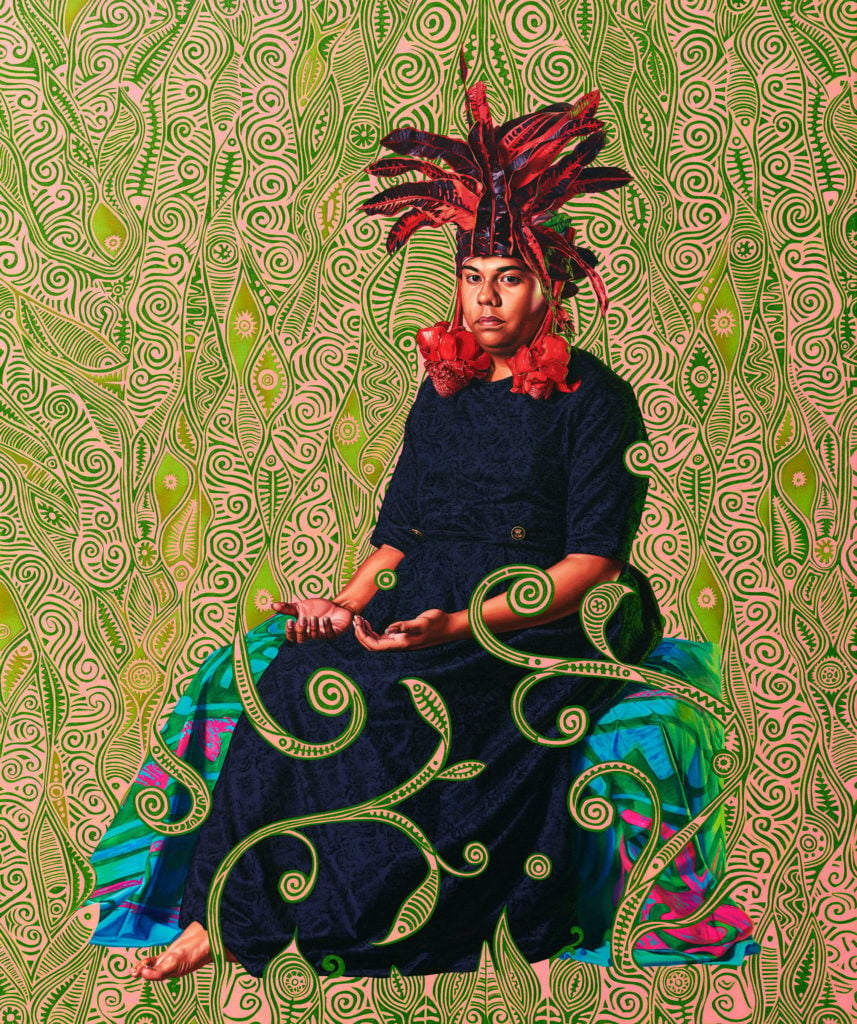

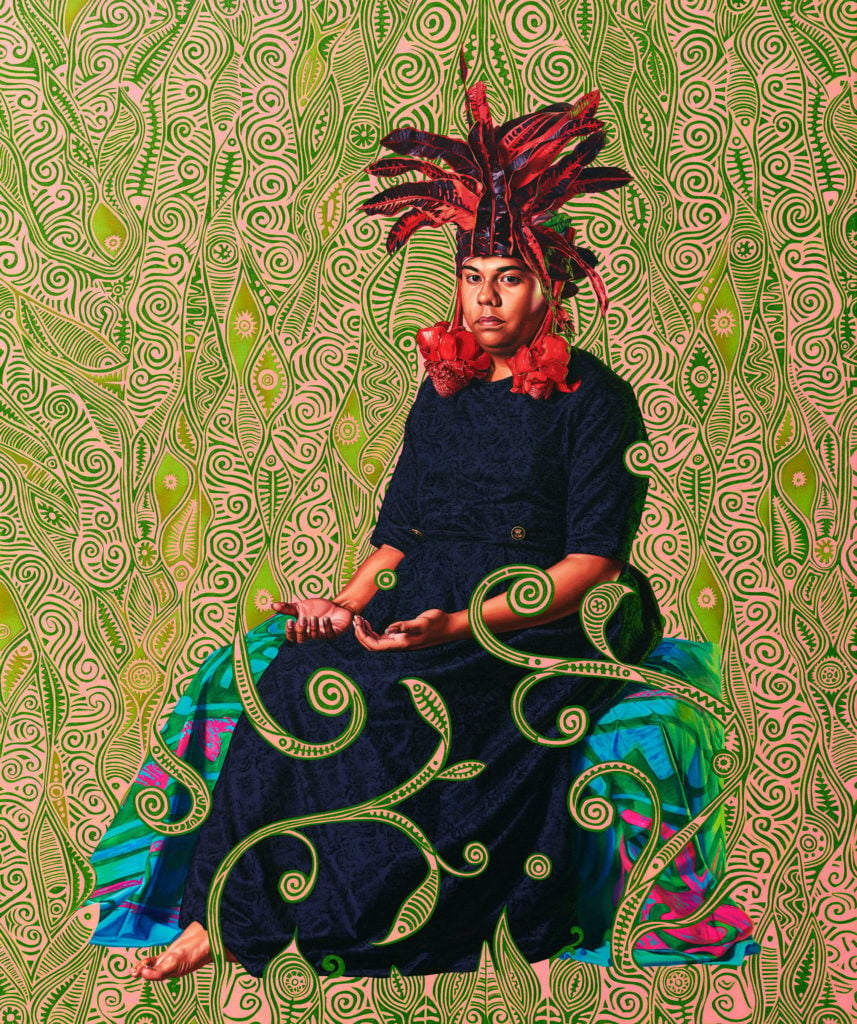

Kehinde Wiley has never been afraid to take on the titans of art history. His captivating portraits have retroactively given contemporary black bodies all the trappings and postures enjoyed by the privileged subjects that populate white, Western art history. And in a new show in Paris, Wiley is taking on one of that history’s most infamous chauvinists: Paul Gauguin.

Wiley’s exhibition, titled “Tahiti – Kehinde Wiley,” opens May 18 at Galerie Templon, and is his first show in Paris since 2016. It consists of a new series of paintings as well as a video installation, all of which are inspired by time the artist spent in Tahiti over the past year.

For those versed in art history, talk of the small Polynesian island conjures images of the erotic idyll invented by Gauguin during his time there at the turn of the 20th century. However, the painter’s calculated representations of island paradise, peppered with exotic beauties, were unlike its realities, and his style was designed in large part to titillate his colonial French audience and bolster his market back home.

Kehinde Wiley. Photo © Brad Ogbonna. Courtesy Templon, Paris & Brussels.

Gauguin was particularly fascinated with the island’s Māhū community, a group classified in traditional Polynesian culture as being of a third gender that exists somewhere between male and female. These non-binary figures are depicted in his work as sexual objects—and as fantasies of colonial exploitation.

In his new paintings, Wiley has also taken on Tahiti’s Māhū community as subjects, although he has done so in a very different way. “Gauguin is not the muse but rather the provocation,” Wiley told artnet News.

Wiley first encountered the work of the French Post-Impressionist painter when he was still at art school in California. “I felt that they were extremely beautiful images,” he says. “But at that time in my intellectual and artistic development, I wasn’t equipped to truly unpack them.”

Now the artist sees something very different when he looks at Gauguin’s paintings from Tahiti. “What one notices in Gauguin’s work is a type of fantasy in which he is imagining a paradise where he can see himself as a European away from the ‘civilized’ world, engaging in a type of self-realization through the bodies of the men and women who populate his paintings.”

But Wiley’s paintings don’t just problematize Gauguin. For Wiley, a straightforward critique of the exoticism and Orientalism of Gauguin, Gérôme, or any number of painters in a long line of French, male art, would be “trite” in the 21st century. “My job as a looker, as a creator, as a thinker, is to somehow imagine a newness within that bankrupt vocabulary,” Wiley says.

Wiley’s sitters were encouraged to look at Gauguin’s paintings and to take on their own poses for preparatory photographs. In this way, the photoshoot “evolved into a conversation between the sitters and myself about self-presentation,” Wiley says. “A type of personal agency was being positioned in these works in a way that counter-poses the narrative presented in a Gauguin.”

“I believe that because of France’s beautiful and terrible past, it becomes the perfect background through which you can enter the work to be able to fully appreciate the nuance of its historical and cultural significance,” Wiley explains, adding that there is a type of “blindness” that can occur in cities so rich with such rich cultural heritage.

“Sometimes, much as New Yorkers with skyscrapers, the French perhaps lose sight of the true import of the masterpieces that populate their museums,” he says. “This reimagining of a city as a site of investigation, and Gauguin as a worthy rubric, perhaps allows the city of Paris to be as much a character in the paintings as the models themselves.”

The exhibition also marks Wiley’s first significant foray into video art. The video installation on view presents a series of interviews with Māhū women, giving them the chance to speak directly to their personal experiences.

Kehinde Wiley on location filming in Tahiti. Courtesy Templon, Paris & Brussels, © 2018 Kehinde Wiley.

Wiley explains that video afforded “an opportunity to engage the narrative of nature and individuality in the depiction of Tahiti and in the paintings of Gauguin.” Neither a documentary nor a narrative film, the video, according to the artist, is “something that gives a type of emotional temperature to the painting.”

Wiley made history in 2018 when he became the first African American artist to take on the monumental task of creating an official presidential portrait, which he did for Barack Obama. Since then, he has been busy gearing up to launch his own artist-in-residency program in Dakar, Senegal, later this month.

The residency, Black Rock Senegal, is due to run through its first course of residents from June through February 2020. The inaugural residents, soon to be announced, will live and work on site for one and three month intervals. They will be given individual studio space as well as local guides to help them discover the city and learn the residency’s three working languages: English, French, and Wolof.

Black Rock Compound and Waterfront View, 2019. Photo by Mamadou Gomis, ©Kehinde Wiley.

Wiley explains that the project arose from his desire to build a studio space for himself in the country—a place of “amazing cultural interchange,” he says. (And one that, for Wiley, is surprisingly accessible from New York.) But in the process of designing the space with Senegalese architects Abib Diene and Fatiya Diene Mazza, and Senegalese designers Aissa Dion, Wiley explains, “the idea of it becoming a space with a more interactive conversational presence became a lot more attractive.”

“Very soon the principle shifted from that of an individual artist studio, to that of a space for my friends—which evolved into a conversation about this not being just friends, but being the entire community of artists and creators of goodwill,” Wiley says.

Preparing the residency was not always easy. “If I had known how hard it would be, I might not have done it at all,” Wiley admits. “But I am happy to see the results of five years of hard work.”

“Tahiti – Kehinde Wiley,” is on view from May 18 through July 20 at Galerie Templon in Paris.