What do Prince and Andy Warhol have to do with a now-viral dispute between two writers over a Facebook post that inspired a short story about a kidney donation? A fair amount, it turns out.

A recent ruling by New York’s Second Circuit found that Warhol’s use of a photograph of Prince was a violation of copyright law. That decision could have sweeping ramifications for fair use—in the realm of literature as well as fine art.

The influence of the Warhol decision will be tested in a case that has captured the imagination of the Internet after the New York Times Magazine published a deep-dive article titled “Who Is the Bad Art Friend?” earlier this week.

The article recounts a dispute between writers and professional acquaintances Sonya Larson and Dawn Dorland over a short story written by Larson. The story, about a woman’s decision to donate her kidney to a stranger, resembles Dorland’s personal experience doing the same, which she documented in a Facebook group to which she invited Larson and other writers she considered friends. In 2019, Larson sued Dorland for allegedly defaming her and trying to ruin her career; Dorland countersued, accusing Larson of plagiarism.

“It’s a like a law school hypothetical wrapped up with issues of critical race theory and psychology and social media, all mixed into one story,” Gregory Korn, of the Santa Monica firm Kinsella Weitzman Iser Kump Holley LLP, told Artnet News.

The saga began when Dorland donated her kidney in 2015—not to someone she knew, but to the next eligible patient on the donor waiting list. She chronicled the process on Facebook.

Her posts inspired Larson to write a short story about a woman, Rose—originally named Dawn in the first draft—who decided to donate her kidney to an Asian American woman she had never met. But far from celebrating the donor’s apparent altruism, “The Kindest” characterizes Rose’s seemingly selfless act as evidence of a narcissistic white savior complex.

The dispute has drawn eyeballs around the globe because of the schadenfreude for everyone involved—but legal experts say it also reveals the unsettled nature of fair use law and how it applies to artists of all stripes.

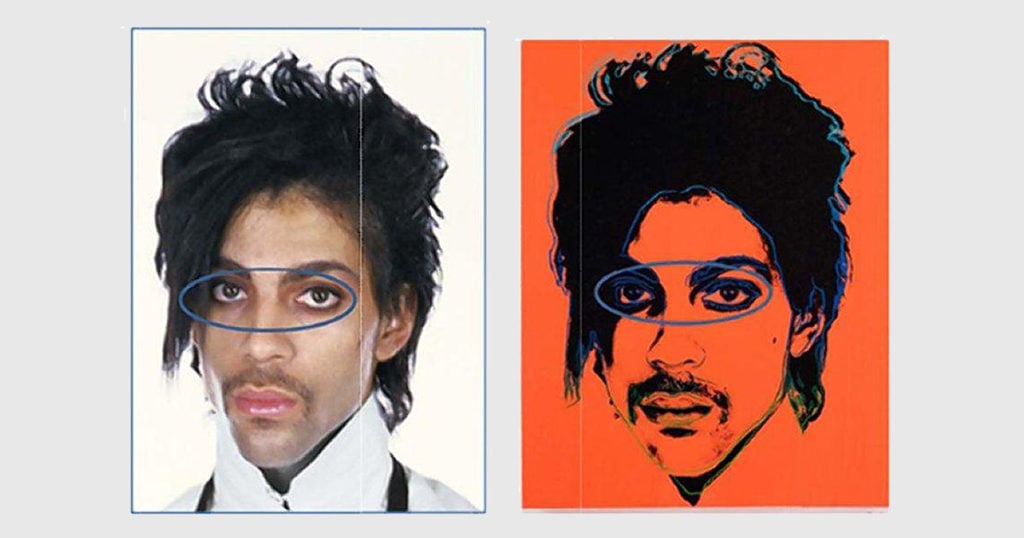

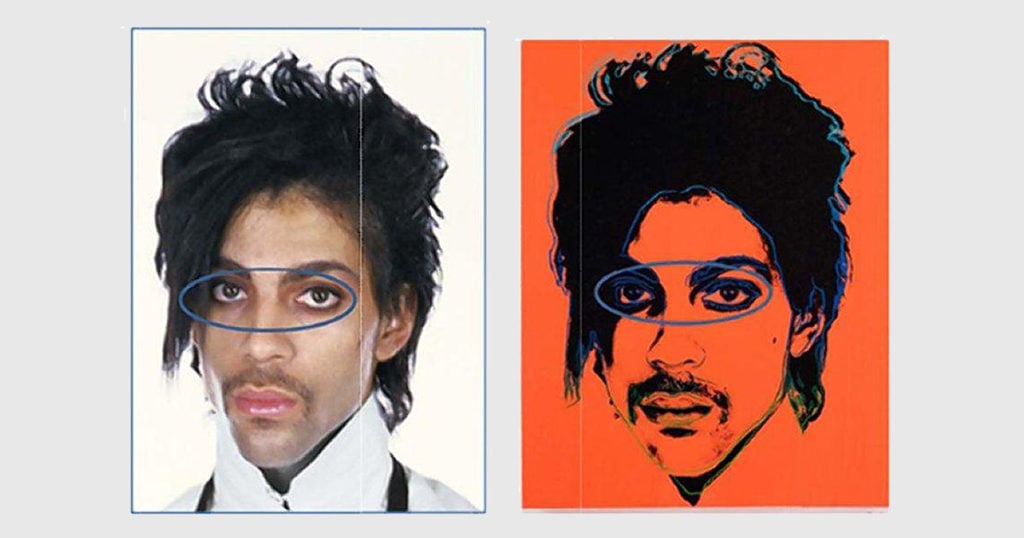

The original Lynn Goldsmith photograph and Andy Warhol’s Prince portrait of the musician, as reproduced in court documents.

Comparing the Two Cases

On one subject, lawyers surveyed by Artnet News agree: the overarching short story Larson wrote is kosher. “You are absolutely entitled to write stories that are inspired by other peoples’ lives, and are in fact are detailed recitations of their lives,” Korn said. “People do it all the time—we call them biographies.”

But there is one part of Larson’s story that makes the situation more complicated. Like the real Dorland, Larson’s protagonist Rose writes an open letter to the recipient of her organ. (“While perhaps many more people would be motivated to donate an organ to a friend or family member in need, to me, the suffering of strangers is just as real,” Dorland wrote in her note on Facebook.) In early drafts of the story, Larson used Dorland’s letter almost word for word.

“It literally has sentences that I verbatim grabbed from Dawn’s letter on FB,” Larson admitted in a 2016 text turned over during the lawsuits’ discovery phase. “I’ve tried to change it but I can’t seem to—that letter was just too damn good.”

After the first version of “The Kindest,” with the original version of the letter, was published on Audible in 2016, Larson revised it, and adjusted the language further. The two versions of the story could determine whether Dorland has a case—and whether the Warhol ruling, which dramatically limits what can be considered fair use, counts as precedent.

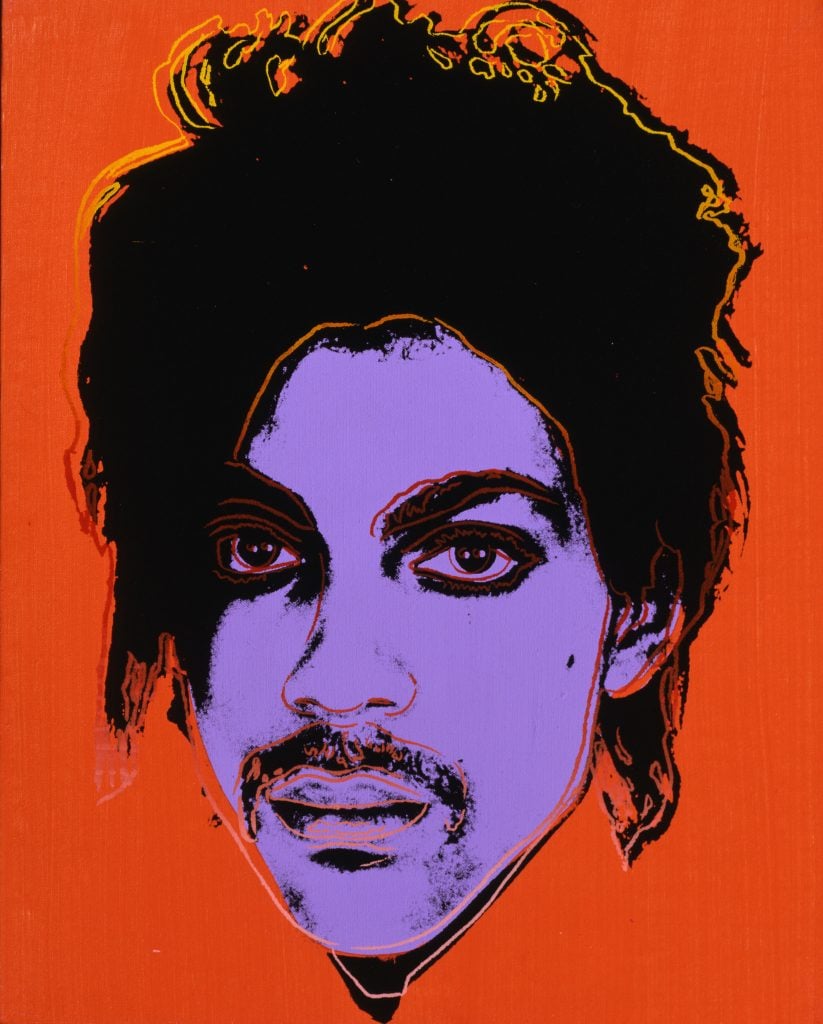

The famed Pop artist created his “Prince Series” of colorful silkscreens in 1984 as part of a commission from Vanity Fair, based on a portrait of Prince taken by celebrity photographer Lynn Goldsmith in 1981. When Prince died in 2016, the magazine asked the Andy Warhol Foundation for permission to reproduce the portrait. The magazine did not credit Goldsmith, but she instantly recognized her photo, setting in motion a copyright dispute.

In March, Goldsmith won the case on appeal. The judge found that Warhol imposing his own artistic style on the original photograph wasn’t sufficiently transformative to meet the standards of fair use.

“It’s a radical decision,” New York University law professor Amy Adler told Artnet News. “It severely constrains and restricts fair use.”

The kidney case is being heard in Massachusetts, in the First Circuit, so the court is not bound by the Warhol decision. But other districts will almost certainly take the high-profile ruling into account when considering copyright cases, lawyers told Artnet News.

Whether or not courts will choose to translate the Warhol opinion from the realm of visual art to music and literature remains to be seen. While much of the language in the Warhol case is specific to visual art, “fair use law is a total mess, bottom line,” Adler said. “It’s so enraging and interesting to try and make sense of.”

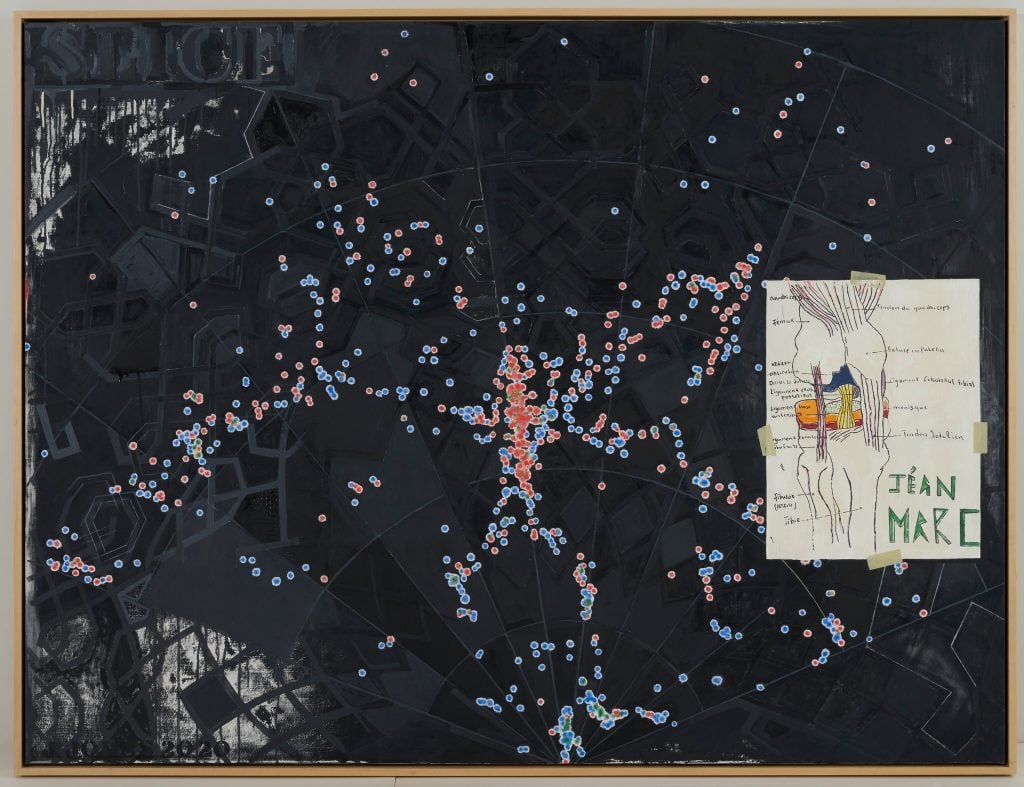

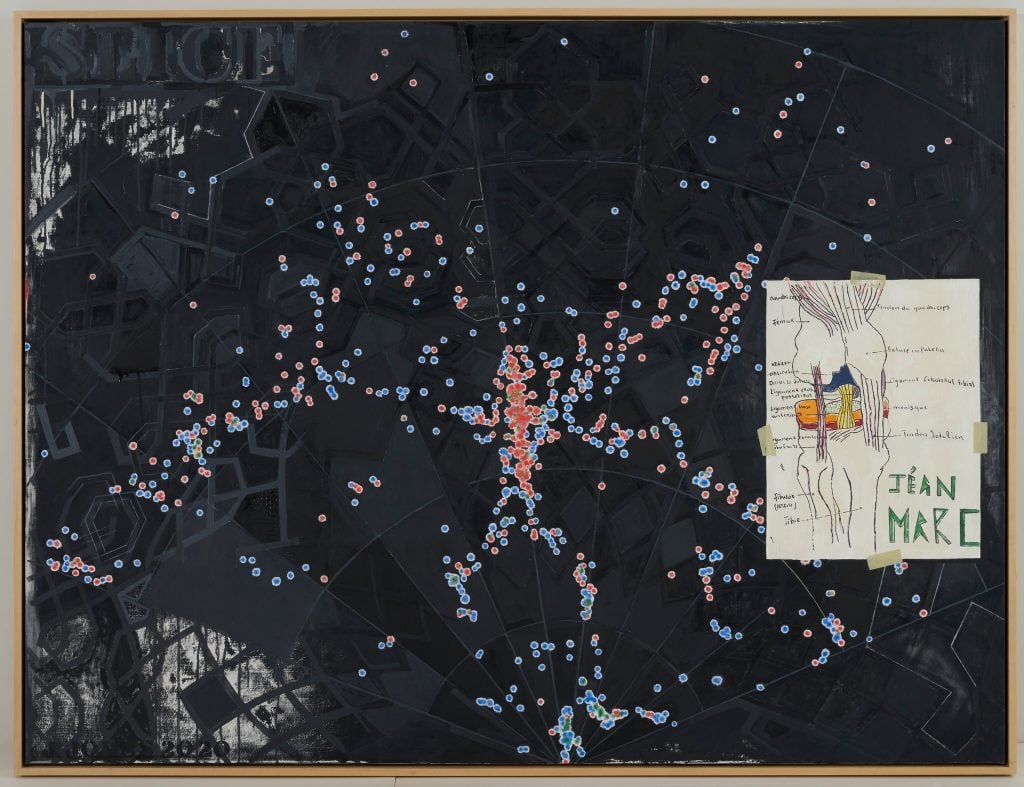

Jasper Johns, Slice (2020). Courtesy of Jasper Johns/VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Fair Use: Authors vs. Visual Artists

Perhaps an even better corollary to the kidney dispute than the Warhol case is the recent settlement between Jasper Johns and 17-year-old Jéan-Marc Togodgue after the artist incorporated the teenager’s drawing in a new painting, Slice, currently on view in his retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

“It’s basically artists stealing from the other artists—and then of course there’s the politics,” Sergio Muñoz Sarmiento, of the Art and Law Program in New York, told Artnet News. “There’s this young Black man, and he comes from an impoverished background and drew this beautiful drawing his for doctor, and Johns allegedly took the image without asking him first.”

This raises another important layer of fair use: how much did the borrower change the source material? The judge in the Warhol case deemed the Pop artist’s Prince portrait insufficiently different from Goldsmith’s. But when Larson revised Dorland’s words in the later draft of the story, did she do enough to avoid infringing?

Many legal observers say yes. “We’re not even in the universe of copyright infringement—we are lightyears away from it,” Korn said.

“Copyright does not protect ideas,” said Dean R. Nicyper, a New York partner at the firm Withers, explained to Artnet News. “It protects expression of ideas.”

Another point in Larson’s favor: Even her early Audible version of the story, which retains most of Dorland’s original language, does not deprive Dorland of a potential market.

“She wasn’t commercializing the letter. She shared it in a Facebook post,” Korn said. “This letter has been taken and becomes a springboard for a whole other story. Larson has a good argument that is criticism and satire.”

Another question is whether Dorland’s letter is original enough to be protected by copyright in the first place.

“We could call it a donative letter. If you donated a work to MoMA and wrote a letter, that’s a donative letter,” Sarmiento said. “If I copied but what I copied is not protected by copyright, there’s no infringement.”

That’s the argument Larson has made. “Her letter, it wasn’t art! It was informational,” she told the Times. “It’s like language that we glean from menus, from tombstones, from tweets.”

Which Is Harder to Prove?

Experts are divided on whether it is easier to prove infringement in visual art or the written word.

“When you look at literary works, it’s easier in some ways to do a comparison. You look at the actual words and the placement of the words in the clauses, and see which ones match up. It’s a little more difficult with visual art,” Nicyper said. “Even though you have the line of Prince’s face and hair, the way that an artist can recreate that could have various nuances that are not as readily identifiable.”

“It’s a little easier in the visual realm,” Sarmiento countered, “because you can juxtapose both images and say ‘does the secondary look like the first? Does the secondary piece transform the first?’ In the written case, it’s a little bit more harder because we express ourselves through language. Ideas are a little bit harder to manifest in writing. Copyright is going to verge on the idea/expression dichotomy—is that an idea or is that expression?”

With the Warhol ruling now part of the body of law in the U.S., artists of all stripes might do well to be wary of potential lawsuits.

“If you’re so directly referencing another work, don’t copy, or get a license,” Adler said. “I think that advice is overkill in terms of what the law actually requires, but think it makes good business sense—even if it’s not good artistic sense.”

At the same time, the question of fair use is undeniably complicated by the issue of art.

“There’s thing where artists are are given a little bit more leeway because they’re artists. But should they be?” Sarmiento asked. “What if the appropriator was Donald Trump’s speech writer? We’d been having a very different conversation.”