Art & Exhibitions

Klaus Biesenbach on Why the Berlin Biennale Still Matters

It was a notorious, now legendary, time in Berlin.

It was a notorious, now legendary, time in Berlin.

Rozalia Jovanovic

When the 9th Berlin Biennale, which is curated by DIS Collective, opens on June 4, it will reveal new work by some of the most exciting artists working today including Amalia Ulman, Josh Kline, Camille Henrot, Lizzie Fitch and Ryan Trecartin, Korakrit Arunanondchai, and Hito Steyerl.

Initiated in 1996 by Klaus Biesenbach, Director of MoMA PS1 and Chief Curator at Large at MoMA, the Berlin Biennale was an outgrowth of a slightly older arts organization that Biesenbach co-founded in that city, the Kunst-Werke Institute for Contemporary Art (KW).

Through his work with KW and the Berlin Biennale, Biesenbach has worked intimately with the artists drawn to Berlin in its earliest, most exhilarating “post-wall” days, and was instrumental in transforming the city into a mecca for experimentation in art, a reputation that it retains today. But in the dizzying landscape of global biennials in cities like Gwangju, Marrakech, and Istanbul, the Berlin Biennale still remains one of the most anticipated shows of its kind.

On the occasion of this year’s biennial, Biesenbach shared his thoughts with artnet News on the founding of the exhibition, its scrappy roots—that nonetheless involved what are now some of the biggest names in the art world, the intriguing history of its predecessor KW, and the continued relevance of biennials for contemporary art.

Manfred Pernice’s wooden tower in the former studio of Albert Speer (Adolf Hitler’s chief architect) at the first Berlin Biennale.

artnet News: What is a biennial to you?

Klaus Biesenbach: I think in the best case, a biennial, and any one of these large art exhibitions, brings together contemporary art in the here and now of the installation in a way that a certain vocabulary and form become apparent, an approach to a specific content and meaning, or just a moment, a movement or even a generation become clear.

With DIS Collective (the curators of the 9th Berlin Biennale) being this post-internet, very digital, affirmative and at the same time critical approach, I think it captures the current generation of artists from Ryan Trecartin and Camille Henrot to Korakrit Arunanondchai, Simon Denny, and Yngve Holen. I think that’s incredibly exciting. DIS doesn’t only include work that couldn’t have been generated without digital media but also places interventions and images in social media very naturally as one additional form of expression. This biennial is somewhat site specific, but much more so time specific and of the moment with all the issues, challenges and opportunities daily social, political and artistic life poses in summer 2016.

That’s what you wish a biennial, or a Documenta will do: capture the art of its time and have the critical mass be more than a sum of all the different parts. It’s more than that, it puts together a larger view, and allows you to look at a certain attitude, a form, an approach of a certain time.

Has the spirit of the Berlin Biennale changed since that time?

I think once again it’s run by an artist collective, DIS, and I think they’re bringing it right back to the beginning. Being artist-centric and being cutting edge and experimental.

Hans Ulrich Obrist, Nancy Spector, and Klaus Biesenbach at the time of the first Berlin Biennale.

Image: Courtesy of Sylvia Plachy

Tell me about the beginning. How was the Berlin Biennale founded?

I went to the Venice Biennale in 1993—it was my first Biennale. There used to be a more emerging, younger artist exhibition there called Aperto. In 1995, we—the artists and curators from “post-wende” Berlin [after the reunification of Germany]—thought we should all be involved. But in 1995, it was a very conservative Biennale and the director, Jean Clair, was like, “I’m not doing Aperto.”

So, with no young art section, we made it ourselves. We rode on a night train to Venice and made a 72-hour-long performance marathon-one of the first Internet congresses happened there, in an old opera house in Venice; it was called Club Berlin and it was carried by Mercedes Bunz, Daniel Pflumm, Monica Bonvicini, Dan Graham, Katharina Sieverding, Angela Bulloch and many more artists. No sleep for three days and three nights, videos, experimental music, installations, talks, performances and screenings parallel to the opening of the official biennial.

We were exhausted afterwards. We thought, wow, we actually could do this in Berlin much more easily. That’s where the idea was born.

In 1996, a year later, I invited art philanthropists and collectors with first and foremost Eberhard Mayntz and including Erika Hoffmann and Raymond Learsy among them. We sat down and said why don’t we start a Berlin biennial. It was a complete self-invented thing. We’re going to invent a biennial. And so we had a group of first supporters.

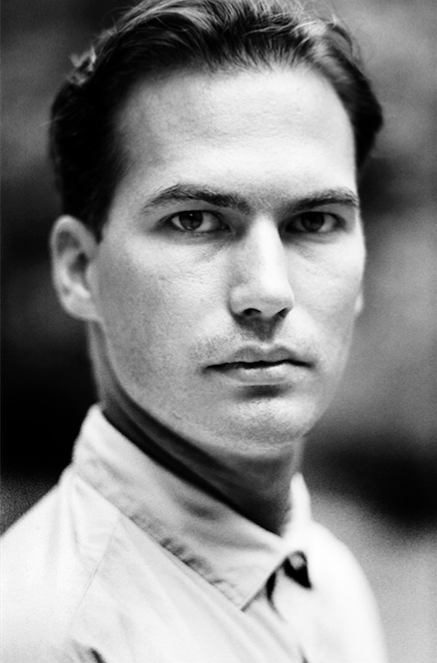

We also had Kunst-Werke Institute for Contemporary Art (KW), the organization I co-founded with Alexandra Binswanger, Alfonso Rutigliano, and Philipp von Doering. It was still a construction mess and an old ruin. Because it wasn’t renovated. If you see these pictures, it’s scary. You would not recognize the building and you would definitely not recognize me sitting right in the midst of the construction mess trying to organize our exhibitions.

In 1997, we had a guest appearance at Documenta called Hybrid Workspace. It was like Club Berlin but more performance and Internet oriented and it had an all-red media architecture like a TV studio by the architect Eike Becker. And the artist Christoph Schlingensief made a performance about German terrorism in the 1960s that was so real that he got imprisoned by the police off our stage. It was quite a “real live” performance to get him freed again.

Berlin Biennale sounded so official—well now, it is official. But if you’re a bunch of youngsters, founding it was a bit of a steep claim. But we did it. And in 1998, we really opened the first Berlin Biennale.

Thomas Demand at the first Berlin Biennale.

One picture you see, I’m sitting in the construction site. We had a huge problem even finding locations. We did use the old Akademie der Kunste at the Brandenburg Gate. We used the old Postfuhramt.

I had invited Nancy Spector and Hans Ulrich Obrist to develop the concept of a biennial for Berlin with me, to build a team and find the artists and they contributed absolutely tremendously. But in the beginning and in the end, I was the initiator, and therefor responsible for it being realized, produced, paid for, and installing and opening it on time against all odds. Daniel Best, Ulrike Kremeier and a very young Jens Hoffmann, now the deputy director of the Jewish Museum, were on our curatorial team and had strong voices.

We called it Berlin Berlin, for East Berlin/West Berlin, but also New Berlin/Old Berlin.

Carsten Holler’s slide at the first Berlin Biennale.

But the most important thing—because we had so many artists and concepts to realize—was that we learned we could only do this if we worked with our generation of artists who were mostly or partially based in Berlin in the nineties: Wolfgang Tillmans, Douglas Gordon, Gabriel Orozco, Olafur Eliasson. Pipilotti Rist, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Andrea Zittel, John Bock, Rineke Dijkstra, Thomas Demand, Elmgreen and Dragset, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster , Thomas Hirschhorn, Xavier Leroy, Manfred Pernice, Stan Douglas, Monica Bonvicini, Ugo Rondinone.

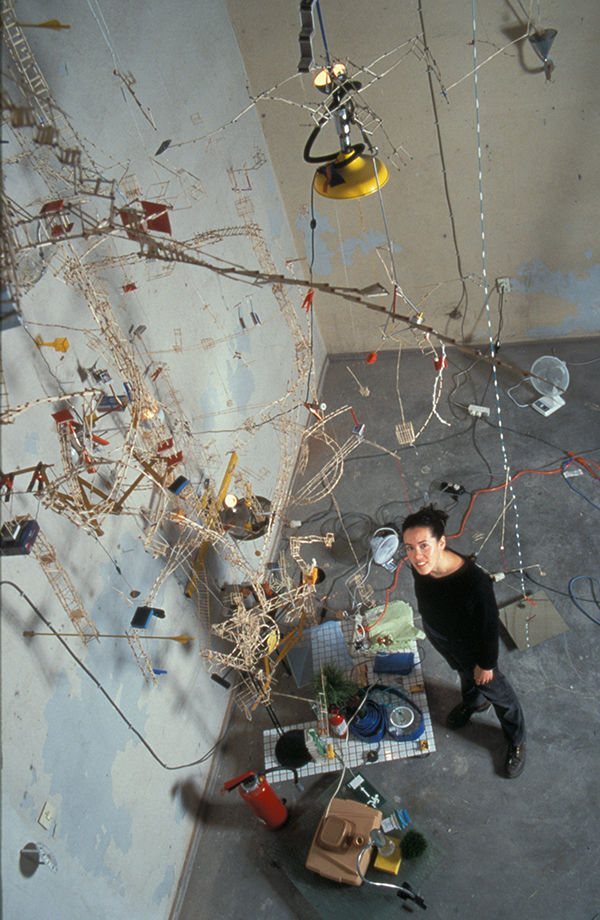

We invited Carsten Holler to do the prototype to his big slide, from the third to the second floor and then going through the window in a transparent tube sliding outdoors and ending back in the building. I had invited Sarah Sze; she was relocating to Berlin for half a year and did a major piece next to an impressive and fragile wooden tower by Manfred Pernice in the former studio space of Alfred Speer (Adolf Hitler’s chief architect), which was a ruin then. It was literally a generation show. And it laid the groundwork for the Berlin Biennale still happening today.

It was kind of this notorious, now legendary, time in Berlin when everyone wanted to move and have a huge studio for nothing, open a club or a store and explore possibilities. As a consequence, the first Berlin Bienniale had so much press and in the end we could get all the support to produce major new artworks.

What differentiates the Berlin Biennale to your mind from other similar exhibitions, like the Venice Biennale?

The Venice Biennale is a state founded exhibition that has national representation in national pavilions. Whereas the Berlin Biennale is truly international, and truly only art-oriented. Several artists have curated it. Maurizio Cattelan curated one with Massimiliano Gioni and Ali Subotnik. Artur Żmijewski curated one and that was quite a radical artist’s statement.

Now, think about the Berlin Biennale, think about it 20 years earlier or KW even 25 years earlier, it was incredibly grass-roots and very improvised. It was a self-proclaimed team that was learning by doing. I think that’s a very different way of starting an institution. It’s not a national or state representation-oriented biennial. We were post-national, we called it “glocal”: global and local at the same time, a phrase I see now used every now and then. But we were criticized for it.

Sarah Sze at the first Berlin Biennale.

How has the Berlin Biennale changed since it first started?

The biennial grew out of KW. Both KW and the Berlin Biennale are now state funded and federal institutions. But that wasn’t how it was when it was founded. KW was a very different and unique constellation as you could do this only in “post-wall” Berlin.

In 1990, I was 23 and an unofficial intern at the cultural administration of East Berlin, the capital of the other Germany, the GDR, and we were assigned to realize a big industrial building, a former margarine factory with 2 courtyards and with a Baroque front house, and we housed lots of artists’ studios there in walking distance from Museum Island and the Pergamon Altar.

After a couple of months, the German reunification happened and the socialist state of the GDR didn’t exist anymore and the interns became “directors”—directors of an abandoned ruin in East Berlin with no staff and no budget and no legal contract to even use the building. As a result of this as a curator establishing working conditions for artists and finding funding was always from the beginning a crucial part of it for me, my first fundraising goal was finding 60 tons of coal to heat the factory with at the artists studios for our first winter.

At that time I basically lived for two years off the grid—no phone, no real apartment, just in a ruin without heat or a roof for the first few months as it slowly grew into its setting.

Klaus Biesenbach in 1992, at the time of the exhibition “37 Rooms.”

Image: Courtesy of Birgit Kleber

Our first large exhibition was recognized, not only locally, but nationally and internationally. It was in 1992 and it was called 37 rooms. I invited 37 curators to curate one room each: a church, a toilet, a basement, several storefronts, a school and so on; the curators included for example Gabriele Horn, who is now the director of the Biennale. There were artists like Felix Gonzalez Torres, Nan Goldin, and Yoko Ono involved. And that was amazing because everybody wanted to come to Berlin after the fall of the wall. Everybody wanted to see what East Berlin was like, Berlin Mitte, the old historical center where we were. It created a huge potential of interest. We had more than 30,000 visitors in one week and we had to tell our local neighbors that this was not the “new normal.” After the show, it was more quiet again in East Berlin.

Slowly, the organizations and the artists we were beginning to work with got more involved: Joan Jonas, Dan Graham, Joseph Kosuth, Katharina Sieverding, Marina Abramovic. It was like inviting your own admired art professors to work with and to learn from.

KW’s decrepit courtyard in the early 1990s.

What was KW’s reputation around the time the biennial started up?

I think KW at the time was the challenging contemporary art institution that was internationally oriented and really experimental, sometimes politically challenging and at the same time housed in a total ruin without an endowment or a budget. So that wasn’t immediately something that Berlin stood for. I think the Berlin Biennale stood for a whole generation of artists living and working in Berlin.

So it was a hugely broad generational effort to somehow express a different understanding of art. The approach of the biennial was very experimental, very multi-media, very innovative. The first Biennale had nearly no painting in it, but a lot of performance-oriented work: John Bock, Jonathan Mess, Christoph Schlingensief, Honey Suckle Company, which was very unusual for the time. We had our patron saint, Dan Graham, who built Café Bravo, and Miuccia Prada herself organized the opening event, a very glamorous affair in what was essentially still a construction site.

It really established KW as being only about the contemporary and not about being nationally oriented, or having pavilions. It was really only about art and artists, which I think not all biennials are that way.

The first Berlin Biennale.

Tell me about the history of KW.

KW started in a decrepit courtyard in an empty factory, which had just been abandoned when the wall fell. And the front house was a total ruin, it had no roof and there were trees growing through it. And I remember when we first looked at it we thought that could not be restored, but then the front house turned out to be an important landmark. It was Baroque. And the city declared it one of the area’s historically significant buildings. We had to save it.

All in all, the first years was a hugely inventive time. And at the same time, from 1990-1991, we immediately made exhibitions. One of the first artists we worked with was Joan Jonas. She came into the courtyard with Aura Rosenberg and John Miller and their baby daughter Carmen in a stroller and a few artists from New York, and she was one of the first artists I really worked with in the institution and then Tony Oursler, Douglas Gordon, Mike Kelley, Marina Abramovic presented work. We had all these amazing artists and we invited them not only to be there and work on projects but also to teach and talk about their art.

We had our own cafeteria. We had studios. Susan Sontag and the fashion designer Hedi Slimane lived in the building for a while. Schlingensief lived there and had his own cinema and ran a political party with himself as the candidate. Thomas Demand and Monica Bonvicini had studios in the back…. Fischerspooner were in residency and performed most legendarily in Dan Graham’s glass pavilion for the Love Parade. It was more like a multidisciplinary an artist compound with a program both day and night. It was very spontaneous and social. It immediately had a very international outreach through the network of artists we worked with.

The first Berlin Biennale.

We had our own club, called Pogo, with resident musicians and guests DJs and once a month we had a huge dinner in the front house where everybody from the compound, their friends and all the guests who we knew were in the city were invited and ate together and the night wouldn’t end (or ended in pogo)…. that is where Doug Aitken met Hedi Slimane, Taryn Simon met Udo Kittelmann, Malcolm McLaren met Matthew Barney, and on and on.

I lived in that front house until I left for New York. Mondays my apartment was the open bar for all artists in the area from 9pm on. It was designed by Andrea Zittel…. At midnight, the lights went on and everybody needed to leave—the next day was full of new projects.

It was a very informal and generously open time. But I think a lot of what Berlin stands for was really true in that time. You could really start something and just do it.

Tobias Rehberger at the first Berlin Biennale.

With all the biennials happening around the world—Sharjah, Gwangju, Marrakech, Istanbul, etc.—why is the Berlin biennial still relevant?

In recent years more and more people care for contemporary art. So it seems. Contemporary exhibitions had record visitations, but I think there are misunderstandings at play here. On one side there is a superficial enjoyment of art as a colorful background at play but more importantly many new “art lovers” ( apologize for that terrible phrase, but it makes something clear in its awfulness) mistake the art market for what art, the art world and art history really is. Going to an art fair is nothing in comparison to going to a curated exhibition where organizers and artists really cared for the form and the content of the exhibition, not its sell-ability and or the fact if visitors can take small or medium sized colorful pieces home and place them behind their couches and hope they quintuple their value in two years.

Perhaps these large shows also are the occasions for which new relevant work is produced and seen in relation to and at the same time with other relevant art work. And these big shows have the critical mass, and public visibility of making contemporary art present as a challenge and as a statement. They even suggest art still has a disruptive relevance in our society. Berlin is especially relevant as it is the base of so many artists living and working there. That is always the most rewarding audience.

Is the Berlin Biennale more polished than it used to be?

I think it’s still very much low budget in comparison to what it delivers, and therefore still very improvised and grass roots. Which is great. That’s how Berlin is. People thought Berlin would get polished and rich, but it didn’t really. It’s a city that is forever young (and underfunded).

What’s your role in it now?

As initiator and founding director, of both KW and the Berlin Biennale, it really depends on the current curators if they want to have me as a resource and learn from past experience. I’m open to being a resource for any and every curator. But I think it’s very important that they make their own decisions, which they all do.

If you have founded something, you are, by default, connected. It’s like having a child and you are forever the parent whether or not you want to be. It’s just part of your biography. It’s part of how the city and how the art world in Berlin developed. But you have to let it free.

What is the essence of the 9th Biennale or the generation it represents?

That’s the one thing about an exhibition, is that words in an article, interview or documentary cannot even begin to capture it. That’s why I think a show like this is needed. Because it’s a medium and a language in itself. Its critical mass and size is big enough to have its own language that you cannot express with words or anything else but art. The reason these large scale presentations have to happen, and the main reason for supporting such a big show, is that it speaks “the language of art”; that is, a language perceived in time and in the exhibition space, experienced one on one for the visitor, that no other medium speaks.