On View

One of Knoedler’s Rothkos Is Heading to a Museum—for a Forgery Exhibition

The painting is on loan from a lawyer who worked on the case.

The painting is on loan from a lawyer who worked on the case.

Sarah Cascone

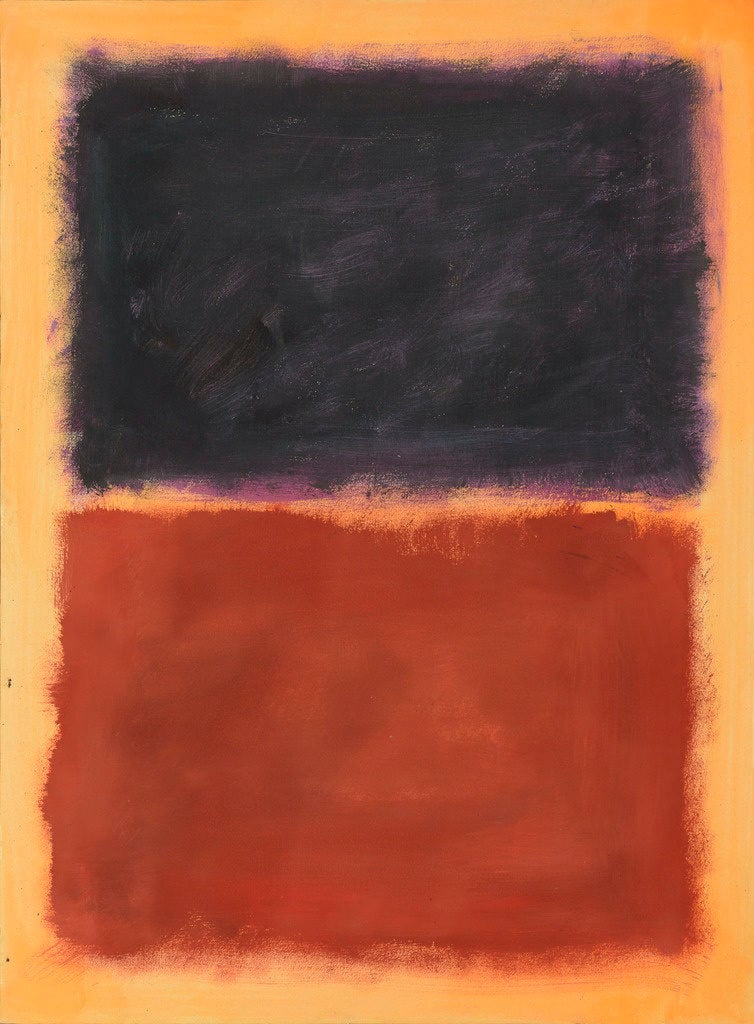

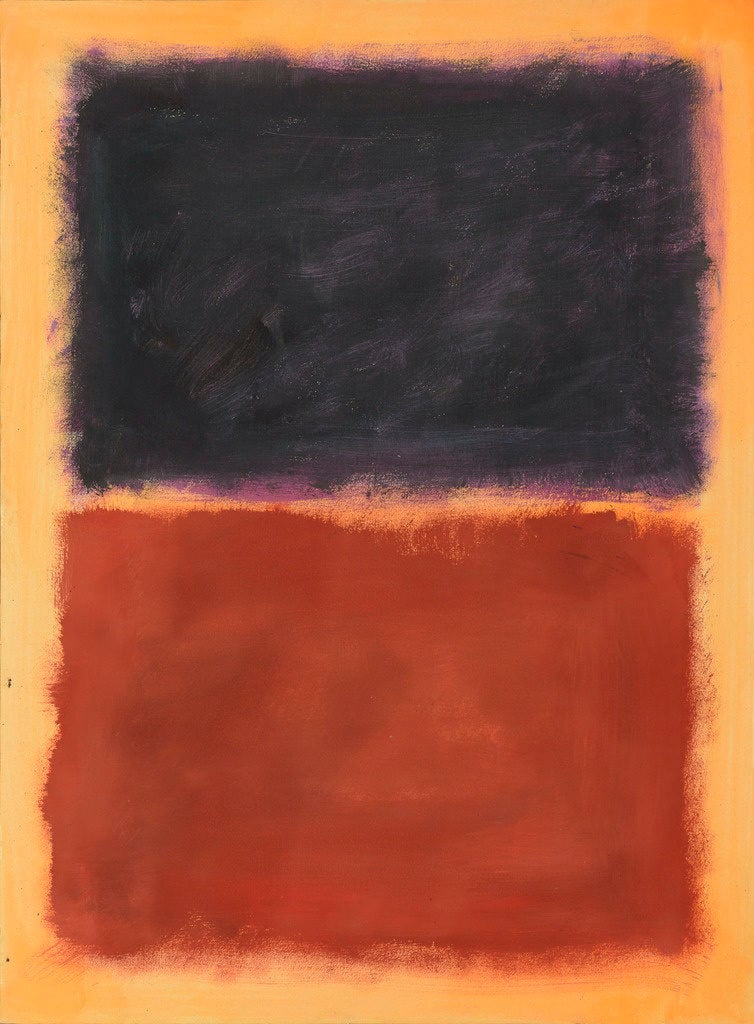

An artifact from one of the most notorious art forgery cases in recent years is going on public view this summer. A fake Mark Rothko sold by New York’s now-defunct Knoedler Gallery is among the counterfeit artworks in “Treasures on Trial,” an exhibition at Delaware’s Winterthur Museum.

The exhibition contains over 40 counterfeit or fake objects, including a baseball glove that sold for $200,000 even though it definitely did not belong to Yankee legend Babe Ruth, a knock-off Hermes bag outed when its unsuspecting owner sent it back to the company for cleaning, and a woolen “Chanel” suit that subbed acetate for silk on the trim.

The most famous of them all, however, is the so-called Rothko, one of 31 fake Modernist paintings sold by Knoedler between 1994 and 2011. Many were purchased by high-profile collectors for six-figure sums—but the real artist behind them was Pei-Shen Qian, a Chinese immigrant living in Queens.

John Myatt’s copy of Vincent van Gogh’s Oleanders

(2012). Courtesy of Washington Green Fine Art.

The canvas comes to the museum courtesy of Luke Nikas, the lawyer for former Knoedler Gallery president and director Ann Freedman. (The gallery and its director have maintained they were unaware that the works were fake; the Long Island art dealer Glafira Rosales, who provided the works to Knoedler, has been ordered to pay the victims $81 million in compensation.)

While cases connected to the forgery ring continue to make their way through the court system, some of the forged paintings have been hanging in Nikas’s office. It’s not bad office art: after all, at least one fake was so convincing that an expert pronounced it “sublime.”

“Not only is it from the Knoedler scandal, but it was the very first picture that Glafira Rosales brought to the gallery and it was purchased by Ann Freedman herself,” the exhibition’s guest co-curator Colette Loll, the founder and director of Art Fraud Insights, told artnet News. “It’s the largest art fraud of the century, we had to have some kind of representation, even though many of the victims, quite frankly, didn’t want to participate.”

Loll hopes the painting will serve as an educational tool that can help prevent future forgery scandals. But placed side-by-side with the real deal, some fakes can be hard to identify. The show includes a pair of identical-looking Tiffany lamps to illustrate that some scams can only be revealed through scientific tests. (The fake lamp contains zinc instead of lead.)

“What this exhibition really tries to show is the role of connoisseurship as well as the role of scientific analysis and how we pull those two together in determining the fate of an object,” Loll explained. “Our mission is not to glorify the forger at all.”

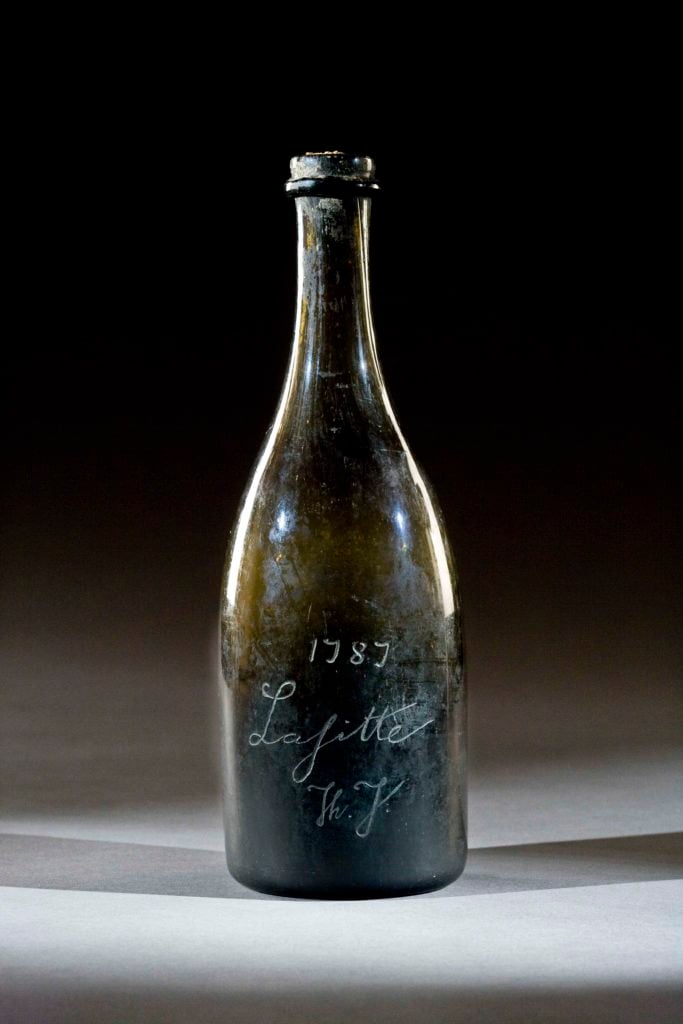

Bill Koch’s fake bottle of 1787 Château Lafite, purportedly owned by Thomas Jefferson. Courtesy of CJ Walker Photography.

Billionaire collector Bill Koch has also contributed one of his less valuable possessions to the exhibition: a fake 1787 Château Lafite bottle sold to him as having belonged to Thomas Jefferson. Koch, who bought the counterfeit vintage in 1988, was one of many wine enthusiasts allegedly taken in by wine dealer Hardy Rodenstock. (Koch later won a civil suit against him in 2005.)

“Even esteemed institutions and sophisticated collectors get fooled,” noted Loll. “Usually at the heart of the story there’s a con man.”

The show also stands as a reminder that some forgeries may never be identified. Famed forger Elmyr de Hory, for instance, is said to have produced thousands of paintings that he passed off as the work of Amedeo Modigliani, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and others. As the forger once put it, “If my work hangs in a museum long enough, it becomes real.”

Co-curator Linda Eaton even told Artsy that she believes that one work in the show is a forgery of a forgery: a copy of one of de Hory’s fake Pierre-Auguste Renoir canvases.

Elmyr de Hory, Portrait of a Woman, in the style of Amedeo Modigliani (circa 1955). Collection of Scott Richter and Pamela Richter-Lenon. Courtesy of the Winterthur Museum.

But debunking a forgery doesn’t necessarily make it worthless. Once identified, some notorious fakes can have a value all their own. As Koch told the New Yorker in 2007: “I used to brag that I got the Thomas Jefferson wines. Now I get to brag that I have the fake Thomas Jefferson wines.”

“Treasures on Trial: The Art and Science of Detecting Fakes” is on view at the Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, 5105 Kennett Pike (Route 52), Winterthur, Delaware, April 1, 2017–January 7, 2018.