Art World

From a Guadalajara Guggenheim to Liverpool’s ‘Cloud’: The 9 Most Audacious Museum Designs That Were Never Built

These never-built museum designs let you delve into alternative histories, parallel presents, and speculative futures.

These never-built museum designs let you delve into alternative histories, parallel presents, and speculative futures.

Naomi Rea

Before an architectural vision is constrained by monetary concerns, urban planning committees, and client preferences, there exists the pure, unadulterated idea contained in the architect’s original plans. There is a trove of alternate histories, parallel presents, and speculative futures to be found in archives of architectural drawings.

Two new shows pay tribute to these unrealized dreams. In London, “ZHA: Unbuilt” at the Zaha Hadid Gallery (until August 18) presents never-made designs by the late architect as part of the city’s Festival of Architecture. In New York this fall, the Queens Museum will open “Never Built New York” (September 17–February 18), inspired by a 2016 book of the same name. The show pays tribute to the New York that might have been through an exploration of original architectural prints, drawings, models, installations, and animations.

For those who can’t wait, artnet News has compiled our own testament to the uncompromising visions and towering ambitions of starchitects. Here is our pick of the nine most audacious museum designs that were never built.

Design for the Helsinki Guggenheim Museum. Image courtesy Myefski Architects, Inc.

In 2014, following an invitation from the City of Helsinki, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation launched an international design competition for a proposed satellite in the Finnish capital. Chicago-based firm Myefski Architects submitted a plan for this futuristic complex made from timber and glass with an epic grass-covered roof that slopes all the way down to the waterfront.

Unfortunately, the slick proposal didn’t even make it into the final six, and the €100,000 ($120,000) winning design came from Parisian firm Moreau Kusunoki. However, neither proposal was ever realized. The Finnish government declined to move ahead with the project in November 2016, citing cost concerns.

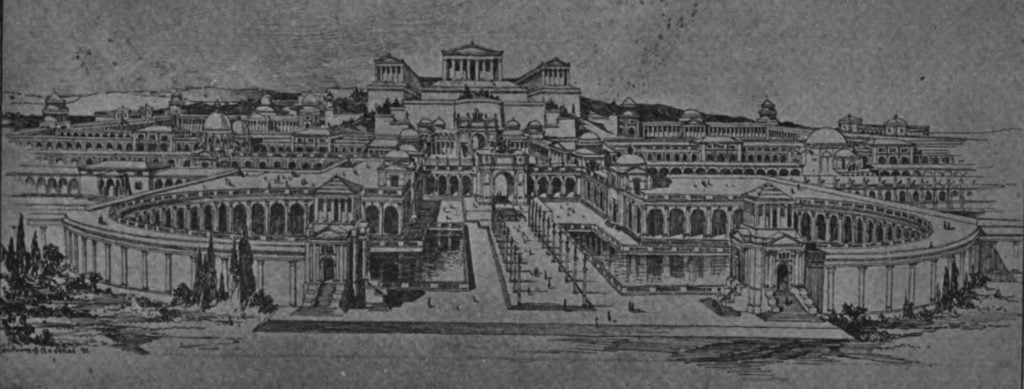

Cover of the 1891 “Design & Prospectus for the National Gallery of History and Art” by Franklin W. Smith. Public domain via Wikipedia.

If Franklin Webster Smith had gotten his way in 1892, the landscape of the National Mall would have turned out very differently. Smith believed the capital should be a strong cultural center, so he drew up schemes for the National Galleries of History and Art. The architect spent years petitioning Congress for support, but the far-out proposal never got off the ground.

The ambitious designs comprised a 62-acre complex that would stretch west from the White House all the way to the Potomac River. The vast compound was intended as a “great systematic educational institution” organized around a wide processional avenue, which itself would be flanked by courtyards representing eight of the world’s great civilizations or epochs: Egyptian, Assyrian, Greek, Roman, Byzantine, Medieval, Saracenic, and East Indian. A triumphal arch would have marked the way to a replica of the Parthenon (50 percent bigger than the real thing) meant as a memorial temple for deceased presidents.

Rendering of Rem Koolhaas’s 2000 Whitney Museum of American Art extension. Image courtesy of OMA.

The Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) partnered with Pritzker Prize-winning architect Rem Koolhaas in 2000 to propose an ambitious extension that would have doubled the size of the Whitney’s existing site. The proposed three-part design took into account the protected status of the four brownstones adjoining the existing Marcel Breuer building on Madison Avenue by proposing to use them as gallery space, intentionally recalling the original West 8th Street Whitney.

Koolhaas proposed a curved 11-story concrete extension with lace-like fenestration, which would have connected the Breuer building and brownstone galleries via a new lobby on level three. But with an estimated budget of $200 million, the project was too expensive, so the Whitney scrapped the plan in 2003, choosing instead to focus on building its endowment. (The rest is Meatpacking District history.)

Enrique Norten’s design for the Guadalajara Guggenheim (2005). Image courtesy TEN Arquitectos.

In 2005, Mexican architect Enrique Norten won a competition to produce a conceptual design for a $180 million Guggenheim outpost in Guadalajara. His 24-story tower—created from gallery modules of varying sizes—would have been visible from any point in the city. Complete with seven high-speed elevators, the vertigo-inducing structure overlooks an epic plunge into the gorge of the Rio Santiago. The whole building appears to float above ground, allowing one of the city’s main thoroughfares, the Avenida de Independencia, to run beneath it.

Sadly, Norten’s tower never got off the ground. In 2009, the project was called off because, The Art Newspaper reported at the time, the Guggenheim’s then-director Thomas Krens refused to scale it back to suit the budgets of the Mexican government and private backers.

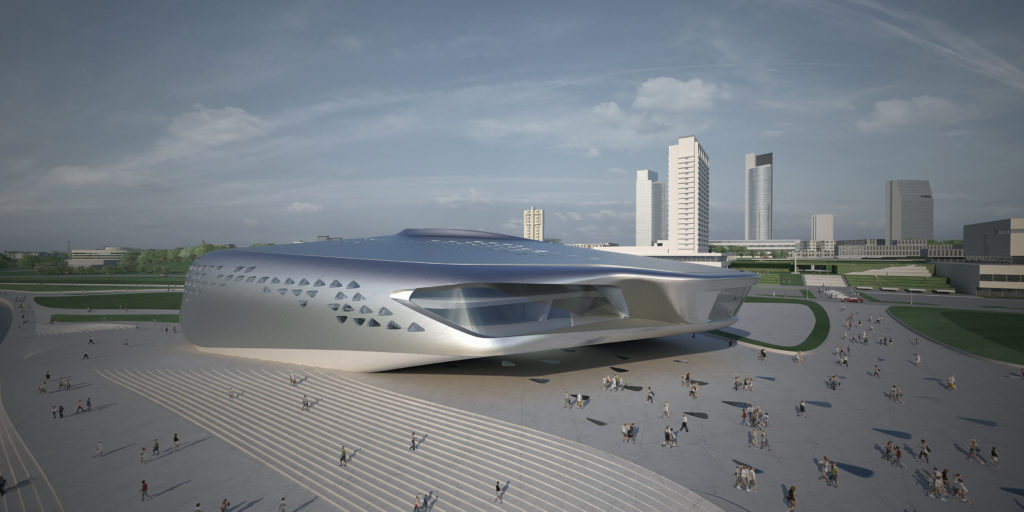

Zaha Hadid’s 2007 proposal for Vilnius Guggenheim Hermitage Museum. Image courtesy of Zaha Hadid Architects.

Yet another foiled Guggenheim dream, this time in Lithuania. In 2007, the State Hermitage Museum and the Guggenheim Foundation joined forces to conduct a feasibility study for a new contemporary art center in Vilnius. British-Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid won the design competition in 2008.

There’s no mistaking the gravity-defying sculptural mass for anything but a Zaha original. The futuristic, curvilinear form contrasts sharply with the rigidity of the surrounding vertical skyline, while exposed dramatic undercuts make the museum appear as if it is hovering over the plaza.

The museum was optimistically scheduled to open by 2011, but was postponed indefinitely in 2010 amid allegations of improper use of funds by the municipality.

Model of the final revised design for the National Gallery Extension, Hampton site, Trafalgar Square, London. Courtesy RIBA.

The architectural trio’s design for the National Gallery extension, created in 1981 as part of a competition launched by the Secretary of State, beat out seven finalists. But it was famously described by Prince Charles as “a monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend.” The prince’s sour evaluation was echoed by the general public, and the design was refused planning permission in September 1984. The long-imagined extension regained traction two years later, when Robert Venturi was elected to design the Sainsbury Wing, now a familiar part of the fabric of Trafalgar Square.

Frank Gehry’s design for the Carré d’Art at Nîmes. Courtesy of Gehry Partners.

Frank Gehry was one of 12 architects, including Norman Foster and Jean Nouvel, invited to compete in a 1984 bid to design a contemporary art museum in Nîmes, France. The design was to replace a Neoclassical theater that burned down in 1952 and intended to complement the neighboring Maison Carré, a perfectly preserved Roman temple from the 1st century BC.

Gehry’s proposal placed galleries atop one another, twisted at skewed angles, with each level accentuated by a theatrical landing looking out on the Roman structure. Slopes and staircases connected all levels, permitting the visitor to explore the outside as well as the inside of the building. The design is cheerfully animated by a bull’s head, which gestures to the region’s tradition of bullfighting, as well as a palm tree and a giant lizard meant to appeal to children.

British architect Lord Norman Foster won the competition with his design for the half-buried nine-story glass cube that makes up the Carré d’Art today. It wasn’t until Gehry won the commission for the Bilbao Guggenheim 13 years later that he was duly recognized by the art world.

Oscar Niemeyer’s proposed design for the Museum of Modern Art in Caracas, Venezuela. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The Brazilian architect—whose experiments with reinforced concrete were instrumental in the development of modern architecture—was invited to design a Museum of Modern Art in Caracas in the 1950s. Niemeyer’s radical idea? To create an enormous inverted pyramid suspended at the edge of a cliff overlooking the center of Caracas.

The proposed windowless structure is opaque and shut off from its surroundings, but natural light streams in through an immense glass ceiling. The jagged man-made lines of Niemeyer’s structure are striking against the soft curves of the natural landscape. Ultimately, however, the instability of the terrain and the potential for earthquakes in Caracas made Niemeyer’s gravity-defying design unfeasible.

Proposal for Liverpool’s Fourth Grace. Courtesy Will Alsop/aLL Design.

In 2003, Liverpool launched a competition to design a building on the city’s waterfront known as the “Fourth Grace.” The project was to complement the Port of Liverpool Building, the Cunard Building, and the Royal Liver Building—which have come to be known as the Three Graces—ahead of the city’s bid for Capital of Culture in 2008.

Alsop’s zoomorphic design, a ten-story balloon-shaped structure, contained a museum (nicknamed “the Cloud”) accompanied by a 389-foot-tall tower with residential, office, and retail space to generate income. Although the Cloud was the winning entry to the competition, the design was axed in 2004 over fears of spiraling costs. It was eventually replaced by the more architecturally conservative Mann Island Development.