Museums & Institutions

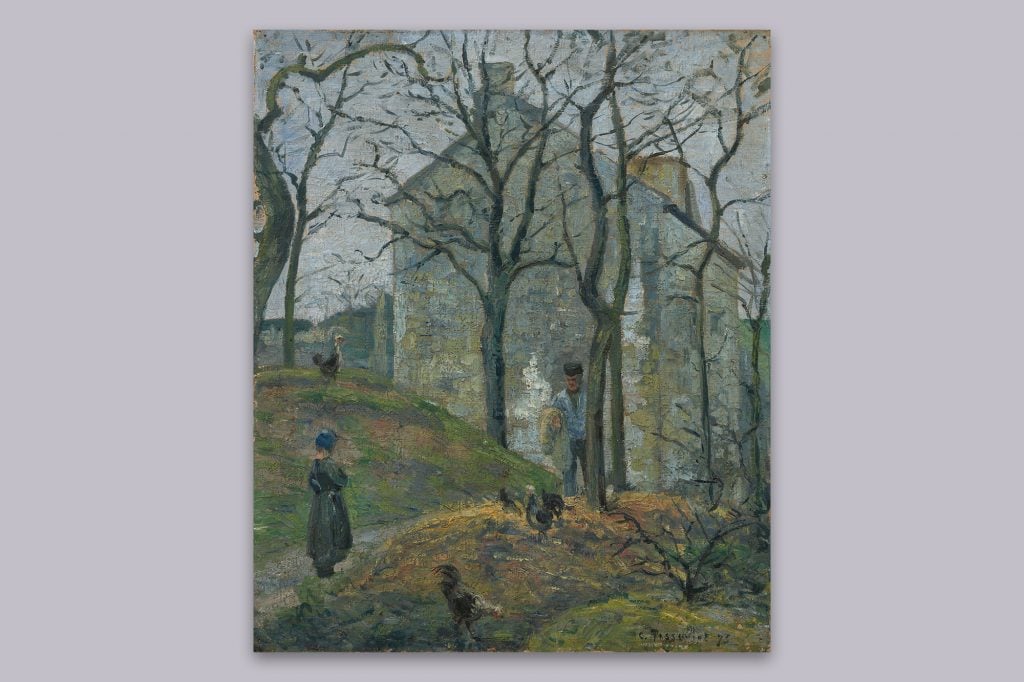

Swiss Museum Settles With Jewish Collector’s Heirs Over Pissarro Painting

Berlin collector Richard Semmel sold the work in 1933 as he was escaping persecution by the Nazis.

Berlin collector Richard Semmel sold the work in 1933 as he was escaping persecution by the Nazis.

Adam Schrader

The Kunstmuseum Basel in Switzerland has reached a “just and fair” deal to compensate the heirs of a Jewish collector who sold his prized painting by Camille Pissarro to escape persecution by the Nazis in 1933.

The painting La Maison Rondest, l’Hermitage, Pontoise was created by Pissarro in 1875 and was sold by the artist’s daughter at an auction in 1924 to an unknown buyer that was likely Richard Semmel, a Jewish textile entrepreneur in Berlin. Semmel and his wife, Claire, listed it for sale at an auction at Mensing and Fils in Amsterdam in June 1933, while the businessman was facing persecution for being Jewish and for his politics as a supporter of the Social Democratic Party, which was banned by the Nazi regime.

The painting likely didn’t meet its reserve price and so was displayed again at the Willi Raeber Gallery in Basel in October 1933. Walther Hanhart, a collector, bought it and bequeathed it in 1974 to his daughter, the wife of collector Klaus von Berlepsch.

Von Berlepsch, unaware of the painting’s origins, kept it until he donated it to the museum for an exhibition on Pissarro in 2021. At the time, the museum accepted the donation because the work was listed under a different name and without a picture in an online database to help track Nazi-looted art.

Kunstmuseum Basel. Photo: Mark Niedermann.

After accepting the donation of the painting, the museum did further provenance research and discovered that Semmel had once owned it. In a news release announcing the agreement, the museum noted that it is now standard practice to check provenance before accepting donations.

An interesting aspect of the case is that Semmel’s heirs are not descendants of his, or even blood-related. The childless couple landed in New York where they lived in poverty after fleeing the Nazis. When Claire died in 1945, Richard Semmel was cared for by a Berlin acquaintance named Grete Gross, who he appointed as his sole heir. Gross’s two granddaughters will receive the compensation from the Kunstmuseum Basel.

The museum noted that several institutions have also restituted works to Semmel’s heirs or have reached other solutions with them. Australia’s National Gallery of Victoria, for one, returned Vincent van Gogh’s Head of a Man (1886) to the collector’s heirs in 2014.

Typically, the Kunstmuseum Basel said it makes a distinction between art looted by the Nazis and instances where Jewish collectors sold their works after fleeing Nazi-controlled areas. In this case, Semmel used the proceeds of the sale to pay taxes to the German Reich, which justified to the museum the need to reach a settlement.