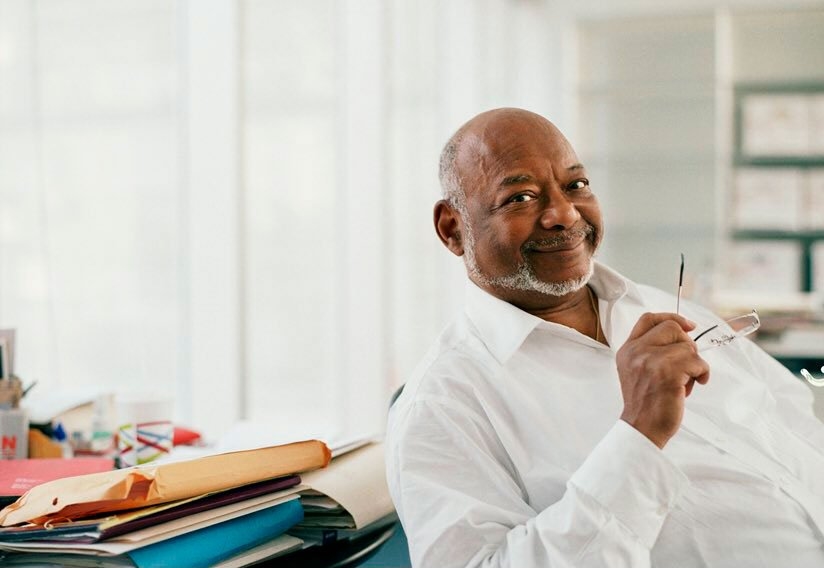

Kynaston McShine, one of the most influential curators of the 20th century, has died. He was 82.

If you have visited a museum in the last 50 years and enjoyed a site-specific installation, participated in an interactive work of art, or been taken aback by a project that critiques the very institution in which it is shown, you probably have McShine to thank.

Over the course of his more than half-century career, McShine organized exhibitions that defined several of the most consequential movements in modern and contemporary art. In 1966, he presented the show “Primary Structures” at the Jewish Museum in New York, which introduced Minimalism to an American audience. (The artist Mark di Suvero called it “the key show of the 1960s.”)

His exhibition “Information,” organized four years later at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, is often considered the first survey of conceptual art in America and one of the earliest shows to examine technology’s impact on art.

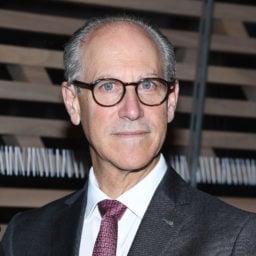

In a statement, MoMA director Glenn Lowry called McShine “a daring and pioneering curator with an unfailingly sharp eye and a keen sense of moment.” When he first joined MoMA in 1959, McShine, who was Afro-Caribbean, is believed to have been the first curator of color to work at a major American museum.

Despite the fact that he crafted some of the most famous exhibitions of the first half of the 20th century, however, McShine remained an elusive figure—he rarely granted interviews, and went so far as to decline Hans Ulrich Obrist’s invitation to participate in the 2008 book A Brief History of Curating. As of 2011, he didn’t even have a Wikipedia entry.

McShine was born in Port of Spain, Trinidad, in 1935. He attended Dartmouth College, where he studied philosophy and worked at the school’s Hood Museum. He did graduate work at the University of Michigan (1958–59) and the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University (1960–62). He taught at Hunter College from 1965 to 1968.

After a stint in the department of circulating exhibitions at MoMA, McShine secured a gig as curator of painting and sculpture at the Jewish Museum from 1965 to 1967. He served as acting director from 1967 to 1968. There, in addition to “Primary Structures,” he organized solo exhibitions of work by Gene Davis, Robert Irwin, and Yves Klein. A statement released by the Jewish Museum described McShine as a “visionary curator.”

McShine returned to MoMA in 1968 as associate curator and later served as acting chief curator of the department of painting and sculpture. In the 1970s, he initiated MoMA’s Projects series, which offered younger artists—including, early on, Sam Gilliam and Nancy Graves—an opportunity to present experimental new work. He also organized solo exhibitions surveying the achievements of Andy Warhol (1989), Robert Rauschenberg (1977), and Marcel Duchamp (1973). He retired from MoMA in 2008 as chief curator at large.

“He was famous for his gruff manner, which masked a warm and deeply affectionate colleague who cared enormously about modern art and the museum that was home to him for more than forty years,” Lowry said.

Bard College gave McShine its award for curatorial excellence in 2003. He has received honorary doctorates from the San Francisco Art Institute (2007) and the University of the West Indies (2008).

The art historian Sarah Edith Kleinman, who is writing her dissertation on McShine, told artnet News that when she began her research a year and a half ago, many people told her he would be impossible to track down. She suspects that his disinterest in self-promotion was a holdover from an earlier era. With the exception of one or two big names like Seth Siegelaub and Harald Szeemann, curators in the 1960s and ’70s “were understood to be ‘behind-the-scenes’ decision makers,” she said. By the time art historians became public figures, “McShine had become entrenched in his unspoken policy of declining interviews.”

Nevertheless, McShine himself redefined the role of an art museum curator over the course of his career. “No longer a behind-the-scenes caretaker of art collections, the contemporary curator that McShine exemplifies is understood as a globally networked practitioner who shares with museum staff the duties of a collaborator, creator, manager, networker, planner, publicist, and fundraiser,” Kleinman said. “In the context of 1950s and 1960s New York City, where curators and artists of color faced blatant discrimination, McShine’s work is even more significant and groundbreaking, opening conversations about the intersections of race, identity, and power.”

McShine sometimes favored projects that needled MoMA’s establishment—but the guiding force behind it all was a fundamental belief in the power and importance of the museum. In “Information,” he allowed Hans Haacke to poll MoMA’s visitors about the views of New York Governor—and MoMA trustee—Nelson Rockefeller on the Vietnam War.

As ARTnews notes, McShine once wrote a memo proposing a show of MoMA acquisitions “which have enriched our collection as a result of Hitler’s Entartete Kunst campaign.” (MoMA’s leadership declined to bite, but the idea ultimately evolved into a show of political art from the collection, “The Artist as Adversary.”)

McShine also, however inadvertently, helped inspire the creation of the Guerrilla Girls. His 1985 exhibition “International Survey of Contemporary Painting and Sculpture” at MoMA—which sought to offer a snapshot of the current state of contemporary art—included 169 artists, only 13 of whom were women. McShine said that any artist who wasn’t in the show “should rethink his career” (emphasis ours)—prompting a group of young artists to gather together to protest.

Despite its demographic limitations, however, that show—like many of McShine’s exhibitions—expressed his belief that the museum ought to present the most challenging and visionary art of its era and never cease to interrogate its own role in the larger machine. In a rare interview with the New York Times, he described the show as “a sign that the museum will restore the balance between contemporary art and art history that is part of what makes the place unique.”

He added: “A serious public cannot depend upon the whims of commercial galleries. It has to depend upon museums.”