Since taking over as design director for Land Rover in 2006, Gerry McGovern has sought to inject the venerable and famously rugged British brand with a dose of high style, transforming its fleet of function-first utility vehicles into eye-catching objects of desire. McGovern’s vision is Modernist. It is reductive. And it is working. Earlier this year, McGovern was the toast of the World Car Awards in New York, where his Range Rover Velar was named 2018 World Car Design of the Year.

Here, we spoke to the award-winning designer about his insights on how the lessons of fine art and architecture can transform off-road workhorses into fine automobiles.

What role did art play in your early growth and evolution as a designer?

From a very early age, I was very visual. I was always drawing, painting. I grew up in Coventry in the early 1960s—the city had been completely annihilated in the Second World War. It was rebuilt in a very international Modernist style in terms of its architecture, which I was very intrigued with. I was always somebody who was more interested in looking to the future rather than looking back, particularly when it came to the visual arts.

An original advertisement for the 1961 Lincoln Continental. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

What kinds of art forms or fields of aesthetic endeavor do you look to for inspiration when creating a new car design?

Car design is a very particular discipline, and I don’t necessarily take inspiration from other things, certainly not consciously anyway. Because the inspiration comes from within. It comes from the brand, it comes from looking forward, it comes from a little bit of looking back. Design, in my view, has some fundamental principles. It has to have good volume and proportions, it has to have a good balance. I suppose the biggest influence on my car design would be the Modernist approach, the Miesian, reductive, less-is-more approach to design.

How would you explain your design process to a layperson?

We have a strong design strategy, which outlines what our direction is, what our vehicles stand for. It talks about certain values, certain details, all these things. But, ultimately, it talks about desirability, because one of the things that we’ve tried to do here at Land Rover over the last 10 to 12 years is give far more prominence to design. In the past, Land Rovers looked the way they did because of what they did. When I came back from America, I decided that Land Rover needed a good dose of design. And to do that, we needed to develop a design strategy that was relevant to a world that was changing massively from when the original Land Rovers were created. The first vehicle that emanated from that strategy was the Range Rover Evoque, which has been a fantastic success for us—and, incidentally, the next version of it will be launched at the Los Angeles Auto Show in November.

Oscar Niemeyer’s Museu de Arte Contemporânea (MAC), Niterói in Brazil.

Who are some of your artistic or creative icons, both from the field of automotive design and more broadly?

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe was probably one of the greatest architects of the last century, as was Oscar Neimeyer. They were two people that I always admired. Lesser known people like Richard Neutra, John Lautner—a lot of these people did their work in America during the Second World War. That’s the beauty of America, it allowed them to develop their talent and their creativity, which probably wouldn’t have happened here in Europe at the time. Artists? Well, you can’t go far wrong with somebody like Picasso. Automotive design-wise, I have a great admiration for the pioneers: Harley Earl, Bill Mitchell, Virgil Exner. Probably my favorite car design is the 1961 Lincoln Continental which was designed by Elwood Engel.

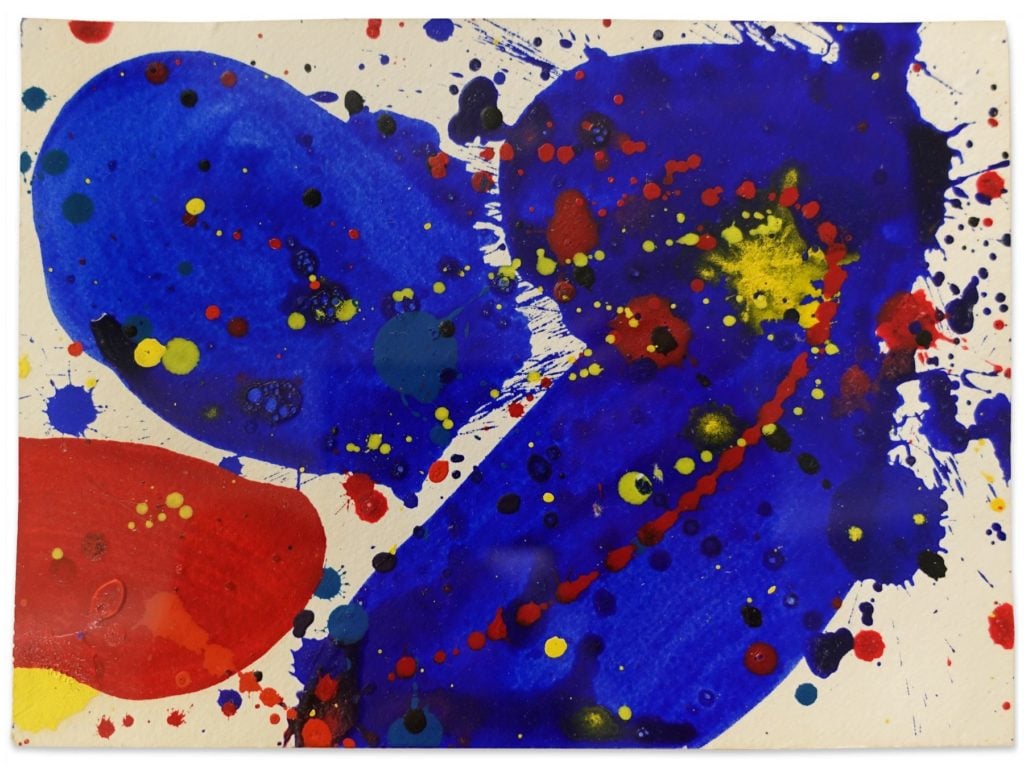

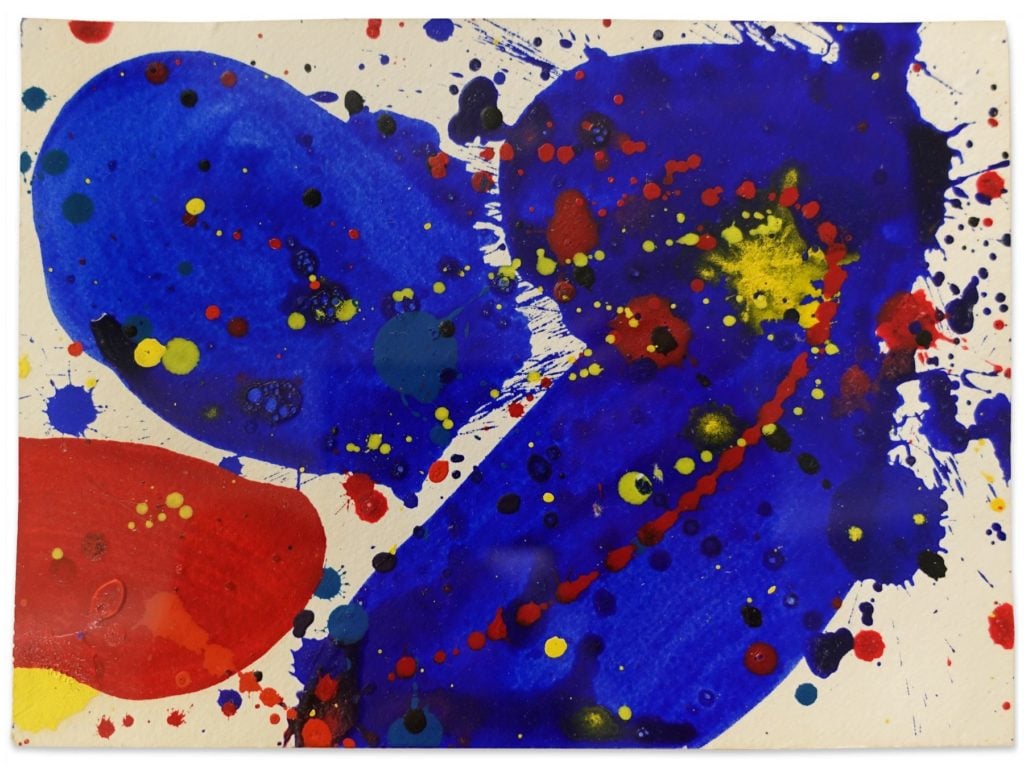

Sam Francis’s Untitled, No. 35 (SF64-628) (1964). Courtesy of Hollis Taggart Galleries.

Do you collect any art? If so, what kind? What are some of your most prized pieces?

I’ve been collecting art for maybe 20 years, ever since I’ve been able to afford it. I tend to be quite selective about what I buy. I do sell as well. I really like printmaking because of the clarity of color that you get on the actual paper, which you sometimes don’t get with oils on canvas. People like Joseph Albers, the founding father of Modernist printmaking. I’m also a big fan of Sam Francis, the Abstract Expressionist. I’ve got some of his prints that are beautiful. There’s one other guy who unfortunately died recently, the Italian painter Nino Mustica. I’ve known him personally for over 20 years, and over that time I’ve collected quite a lot of his bigger canvases. I really love his work. We collaborated with him a few times here at Land Rover where we created some sculptural forms together to celebrate the launch of one or two of our vehicles.

As for prized pieces, well, I better be careful here because I might get robbed! [Laughs] One of my favorite pieces is a Picasso lithograph I bought in Nice some years ago. Some of my vintage Italian glass pieces I really prize as well, as well as my Italian lamps by people like Gio Ponti, who is not only a great designer but is incredibly artistic as well.

How important is style and design to Land Rover’s overall image and raison d’etre, as compared to things like utility and performance? How do you balance the two?

If you’d have asked this question to a design leader at Land Rover maybe 30 years ago, they’d have said, “Well, we’re a functional brand—it’s about our engineering, functionality, durability, and all those things.” To me, it’s far more than that. One of the things we have managed to do over the last 10 years or so is make design a fundamental part of our business. Design is at the core of everything we do. We live in a world now where image is everything. Once things become comparable between one manufacturer and another, whether it’s technology, quality, precision, reliability, connectivity—whatever it is—once those things become comparable, what are you left with? You’re really left with the brand and its essence. It’s design that communicates what that essence is.

Unstoppable Spirit, a sculptural collaboration between artist Nino Mustica and Land Rover’s Design Director, Gerry McGovern.

You’ve described the new Range Rover Velar as bringing “a new dimension of modernity” to Land Rover. What does modernity look like in 2018, and why?

The Velar is quite special to me and to us because it represents thus far the best example of what I mean by a Modernist approach, a reductive approach. Because when you look at the vehicle, it is very paired back. Today you see a lot of car designs that have got far too much going on in terms of the design, far too many lines on the body’s side section, too many shapes, too many forms. There’s a lack of clarity as to what those vehicles represent.

What is beautiful about the Velar is that it’s beautifully balanced and proportioned, and the surfaces are beautifully sculptured. You see things like the flush door handles, the flush glazing, the very high levels of precision in terms of the linework. The lamps are very stealth-like. It is a vehicle that truly does resonate on an emotional level. Then when you get inside, it looks harmonious, it creates a sense of what we call “car sanctuary.” In the world we live in of 24/7 connectivity, too much complexity, particularly in the car’s interior, can be an irritant. What we wanted to do with Velar is make that less obvious. The technology, the connectivity is all there. But it’s more intuitive and it’s less visible, in your face. For me, when I get into an automobile, I don’t want to feel like I’m getting into the cockpit of a Boeing 747.

Your Range Rover Velar won the 2018 World Car Award for Car Design of the Year, scoring high marks for “emotional appeal.” As a car designer, how do you appeal to people’s emotions?

I break it down into three levels. One, the visceral level: when I look at it, do I desire it? Two, the behavioral level: once I’ve got it, does it do what it’s supposed to do in terms of its functionality? And, last but not least, three, the reflective level: once I’ve owned it, used it, spent time with it, do I continue to desire it? Does it continue to work properly? And am I building a lasting relationship with it that makes me feel good about the fact that I own it? We try to create products that our customers will literally love for life. That’s a difficult thing in this competitive world. Design is crucial for that.

Land Rover’s Chief Design Officer Gerry Mcgovern poses with the Ranger Rover Velar. Photo by Jamie McCarthy/Getty Images.

How do you see car design evolving over the next decade? What do you think it will take to win Car Design of the Year in 2028?

Well, that’s the million-dollar question, isn’t it? We face some unprecedented challenges in the automotive world. It’s almost a perfect storm. We’ve got all sorts of things coming at us. Electrification—what is going to be the optimum propulsion system? Autonomous driving—what’s that going to mean the way we design our cars? Particularly our interiors! The world of connectivity—how well connected do we actually want to be? The whole issue of car ownership—will we move away from people owning individual pieces of mobility to shared mobility? All these things are going to impact the automotive design. We have to be able to find our own way of embracing that in a way that allows us to continue to produce vehicles that resonate with people on an emotional level. I do think that design will become even more prominent in terms of brand differentiation. I think materials are going to play a much bigger role as well. We’re already seeing, particularly with younger people, an aversion to using animal byproducts in their vehicles. When we came out with the Velar, we used a premium fabric as opposed to a traditional leather.

If you weren’t designing cars, what do you think you would be doing? Do you ever design other objects on the side?

I do other things. I design houses. I even design clothes. But cars are in my blood now. When I was 16, I wanted to be a portrait painter. I remember my art teacher at the time said, “Well, Gerry, this is all well and good, but you know, artists don’t really make any money. Have you thought about car design?” And I always liked cars. That’s what started it. So, what else would I be doing? I don’t know. I’d probably go into the financial world and make shitloads of money. Then I could just have all the art and cars and all the beautiful things I love anyway.

Do you see possibilities for art and cars to become even more closely intertwined? How could the fields collaborate more in a meaningful way?

I think they are. I think perhaps people don’t realize that. For me, a car, at least a beautiful one, is art on wheels, particularly if it’s unique and it’s compelling. The automotive world has gone through periods in its development where cars all became the same, they just became commodities, they became boring. They were created by business plans by manufacturers. I’ve always said you can’t be a manufacturing business and be manufacturing-led. You have to be a customer-led business. You have to give customers what they desire, not just what you’re capable of giving them.