You know what sounds unappealing? Starting a new job as a museum director at a time when your institution is closed indefinitely, you can’t meet any of your new colleagues face-to-face, and art institutions around the world are experiencing historic budgetary shortfalls.

But that’s the challenge that Laura Raicovich, the former director of the Queens Museum, has willingly taken on.

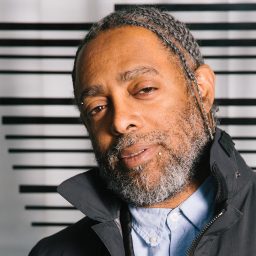

This week, she began her new role as interim director of the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, the big-hearted, beloved New York institution dedicated to queer art. Raicovich replaces Gonzalo Casals, who was recently appointed New York City’s Cultural Affairs Commissioner. An experienced and politically outspoken museum administrator, Raicovich has had stints at Creative Time, the Dia Art Foundation, and the Guggenheim before serving as director of the Queens Museum, a post she stepped down from in 2018 amid a dispute with the board over her activist approach. She is now working on a book about politics in the museum, which is due to be published by Verso in 2021.

Although she doesn’t anticipate holding the job at the Leslie-Lohman permanently (she feels the role would best be filled by a queer person), Raicovich said she hoped to “hand it off in at least as good a condition as it was handed to me.” Earlier this week, we spoke with Raicovich (over the phone, of course) about what it’s like to begin leading a museum you can’t set foot inside.

How do you start a new job as a director when your museum is closed and you can’t meet any of your staff in person?

I’ve been trying to think about what I would do if we weren’t in lockdown and translating that into this new reality, like writing emails introducing myself to all the stakeholders. After this conversation, I have my first all-staff meeting on Google Hangouts. It’s not a huge team: 14 people, plus a handful of teaching artists.

Many museum directors are asked in interviews about their plans for their first 100 days—but this isn’t a typical first 100 days. What are your priorities right now?

I’ve been trying to wrap my arms around the finances, to work with the programming and curatorial teams on what our goals might be, what our exhibition schedule might look like—to invent a reality of future potential and at the same time think about what we can do programmatically right now.

Any transition of leadership creates a lot of insecurity. Now, we have doubled down on that feeling of insecurity on every single front—spiritual, physical, financial—and people need some reassurance.

JEB (Joan E. Biren), BEING SEEN MAKES A MOVEMENT POSSIBLE (2019), façade installation, Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art. ©️ Kristine Eudey, 2019.

How do you give that reassurance at a time when so many museums are making layoffs and furloughing staff and facing serious budget shortfalls?

I don’t know what kind of difficult decisions we might need to make. But I think it’s important to convey that whatever they might be, they will be made with thoughtfulness and care. They need to come from that place of deciding you are going to prioritize caring for people, because cultural institutions are not their buildings and collections, they are their people—from the people engaging with folks who come through the door to the folks who are writing the checks.

What projects are you able to actually start working on?

The museum is launching a new website soon—at the end of April, beginning of May—which is something that was already in the works before all this started. Our program director has a big focus on where queer art and access intersect, and disability activism is something I’m really interested in right now. When we’re talking about digital space, we’re really talking about public space—but that public space is largely controlled by major corporations.

So how does a museum—and a closed museum, no less—start to even think about addressing a problem like that, which is so structural and so big?

We need to be working on a number of different registers simultaneously. What’s funny is talking to you now is fun because, being a glass-half-full kind of gal, everything is full of potential.

I initially started thinking about this project that artist Shannon Finnegan was working on at Eyebeam last year about alt text [words that are embedded into HTML code to describe the appearance and function of an image on a page, which makes the images accessible to those with vision impairments]. We could have Shannon do a workshop with us about how to have beautiful alt text on our site. And then I thought, maybe we should make it public, because a lot of people are taking this time to update their websites, and maybe we can collaborate with other organizations.

On another register, we also started thinking about physical mail. I’m sure every institution is talking about this, too, because everyone knows about the deep and beautiful history of mail art. A friend recently posted something on Instagram asking for people to send their snail-mail addresses, and it was so delightful to get her note. Sure, we could email, but to get this physical thing that she had touched—maybe there’s something a little transgressive about that right now because we are also afraid of touch. We’re trying to be thoughtful about the different registers that might spark people’s imaginations.

The Leslie-Lohman Museum’s most recent exhibition, “Other Points of View.” Photography: ©️ Kristine Eudey, 2020. Courtesy of the Leslie-Lohman Museum

I think this moment has really revealed the precariousness of the museum sector. I know I would feel existentially threatened if I missed three paychecks, but before all this, I would have liked to think that museums were more responsible with their money than I am.

We have a real problem in the United States because we don’t have robust public support for cultural space. I think we need to have a discussion at some point about what culture means in the US and what various publics desire from cultural space.

There are different realities for museums that receive a huge amount of visitors from the public. After 9/11, when I was working at the Guggenheim, part of the crisis was due to the fact that we relied so much on the gate for our revenue—and all of a sudden, international visitors went to nil. The Leslie-Lohman Museum takes a voluntary, almost tip-jar approach, so we don’t have that instability, although our budget is a lot smaller. We have other concerns. Institutions like Dia and Leslie-Lohman have bequests of property that yield income and the fall in potential rental income would affect us more than gate.

The biggest question in my mind is how much philanthropy is going to step up. Also, one of the most important pieces to come out of the federal CARES Act is the Payroll Protection Program. We have applied for that, and I know many other institutions have, too.

There has been a lot of discussion about how museums are making the decision about who to furlough and lay off, and who to keep. As a museum director, how do you even go about making those calls?

That is something anyone in a leadership position is really struggling with right now. And my heart goes out to institutions that have had to make commitments to major furloughs and layoffs. But I also feel like we need to be more creative about how we sustain the people upon whom we rely for the inventiveness, beauty, and connectedness of our institutions.

You know, sometimes your Twitter feed makes meaning, and recently, I saw the announcement that MoMA was cancelling contracts of its educators, and the next tweet was from the Queens Museum that they were going to start doing family workshops online. Of course, different institutions have different priorities and capacities. But if ever there was a time to recalibrate and radically reimagine so many things about our world, and particularly the cultural sector, it is now.

How do you think the museum sector will change in a post-lockdown era?

There are two spaces that I think will shift. One is around collaboration, and a spirit of generosity that I think we need to bring to our work. How can like-minded organizations leverage our close funding contacts to advocate for one another as a consortium? We might go to a large funder like the Ford Foundation and make the case for all of us being important.

The other piece is slowing down. We have been on this race to overproduce: content, programming. I think we are producing too much. It needs to be done more thoughtfully. Maybe it’s all my time working at Dia, but I think we move too fast in changing exhibitions. Before this current crisis hit, I was feeling like there was no way that I could get to even a tiny percentage of the art stuff that was happening—and I love it all. Let’s try to achieve a little more balance.