Up Next

Artist Layo Bright’s Garden is Blooming with Glass Flowers

The Nigeria-born artist uses intricate glass flora to explore complex narratives in her first solo museum exhibition, "Dusk and Dawn."

Layo Bright believes in the language of flowers. Over the past few years, the Brooklyn-based artist has steadily incorporated imagery of blossoms—both real and imaginary—into her glass and pottery sculptures. Flowers, she believes, are the perfect metaphors for migration and cultural adaptation.

The artist was born in Nigeria in 1991 and wields flora as a means of navigating her heritage and experiences, while engaging with broader narratives. “I fuse and cast flowers onto my works,” Bright explained during a visit to her Red Hook studio earlier this spring. “Some of the flowers I include are native to Nigeria. Flowers are symbols of adornment and beauty, but also speak to a migratory effect of and cross pollination of cultures.” Glass flowers, in a rainbow of colors, were scattered across the studio’s various working surfaces.

She pointed out yellow trumpets—Nigeria’s national flower—and skeleton flowers, flowers whose white petals become as translucent as glass when wet. “Flowers are my way of thinking as a person within a new culture and blossoming, too,” she said.

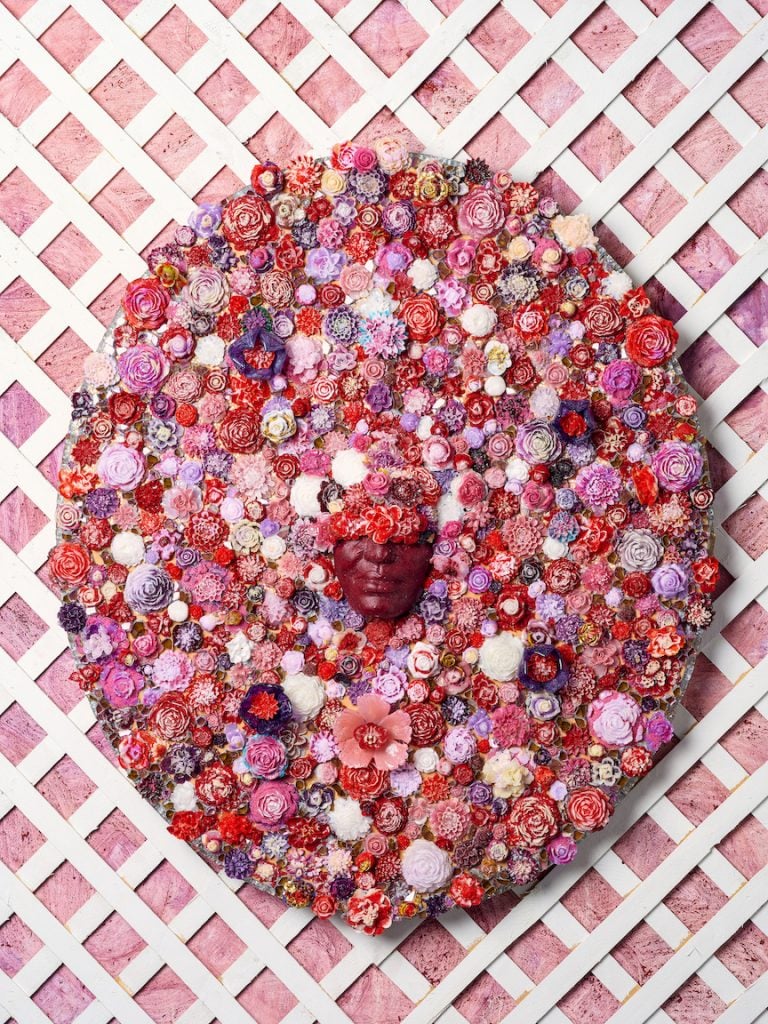

Layo Bright, Bloom in hues of Red, Pink, Purple (2024). Courtesy of the artist.

In this light, Bright’s works have recently come into peak bloom. The artist’s newest works are portraits of the women in her life made in both blown and kiln-formed glass and pottery. First taking casts and making molds of their faces, Bright then transforms the visages of those dear to her—her mother, her sister, her friends—into glass, a material at once fragile and enduring, luminous and forged in fire. She then adorns these faces with glass flowers, covering their eyes with flowers and framing their faces. Sometimes she installs flowers on the walls surrounding these works too, a gesture that calls to mind blossoms blown by the wind, a key element of plant migration.

These new works are some of stars of Bright’s first solo museum show. “Dusk and Dawn” was curated by Amy Smith-Stewart and is now on view at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut (on view through October 27). The exhibition brings together a selection of works made from 2020 to 2024, including loans from private collection, and charts Bright’s concurrent exploration of abstraction and figuration through glass. “Dusk and Dawn” is Bright’s first institutional solo show and a moment of accomplishment for the artist who has quickly emerged as a leading voice in the often overlooked medium.

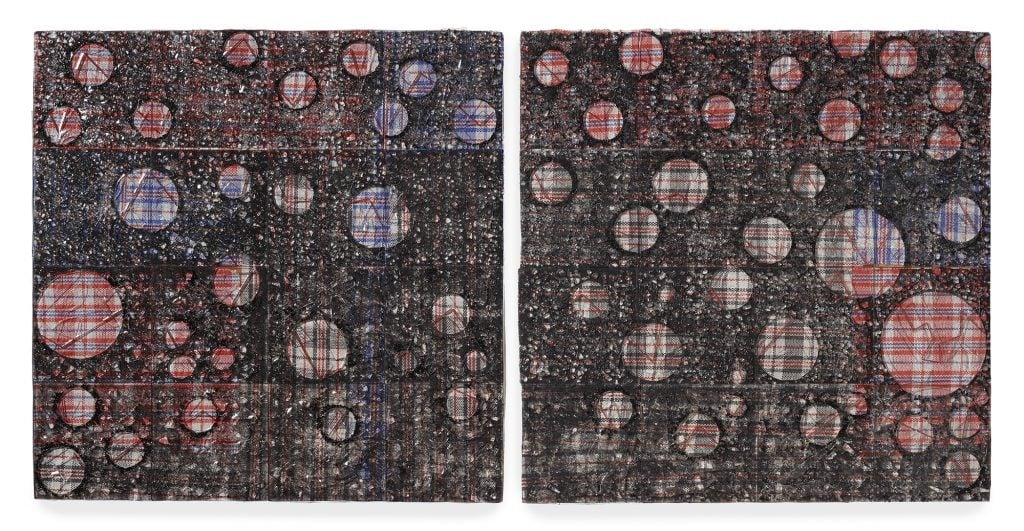

Layo Bright, Horizon Line 1 & 2, (2022/2024). Courtesy of the artist.

In just a few short years, Bright’s earned the support of leading galleries with works included in exhibitions with Monique Meloche in Chicago, Sean Kelly Gallery in New York, and Parts & Labor in Beacon, New York (Smith-Stewart first saw Bright’s work on view here). Last winter Bright took part in a residency at the Museum of Glass in Tacoma, Washington. Recently, she was awarded a residency at the Pittsburgh Glass Center. Her ascent in the art world has been at a clip—Bright earned her MFA from the Parsons School of Design in 2018. Before that, however, she earned a law degree from Babcock University. Though obliquely, her law experience informs her work that blends personal narrative with broader transcontinental social themes.

Portrait of Layo Bright with her Bloom in hues of Red, Pink, Purple, in the background. Photo: Justin Sisson.

“For me, the garden is a symbol of encasement, it’s an attempt to control nature, a kind of restraint,” Bright explained. “I’m interested in questions of identity and culture being constrained, but also finding a way to do its own thing and navigate the world of today, still blooming outward.”

For Bright, the genesis of recent works is linked inextricably to her experimentation with of glass, as well as her ever growing prowess with the medium. Bright admits that her fascination with glass arts was sparked by the Netflix series Blown Away. “I was mesmerized!” she said with a laugh. The artist applied to and was accepted to classes at Urban Glass, a leading glass arts educator in New York. She planned to immerse herself in learning the intricacies of techniques—but when in-person learning was paused in 2020, the artist took learning into her own hands.

Layo Bright: Dawn and Dusk (installation view), The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum. Photo: Jason Mandella. Courtesy of the artist.

“I bought a kiln with a manual of how to program it. A lot of glass making is learning what temperature to take the work up to so the glass doesn’t become a puddle,” she explained. “I fooled around, studied, and researched. I had no one to tell me what not to do and I had to figure things out. It was a lot of trial and error from a year and a half of working alone.” She was eventually awarded a fellowship at Urban Glass.

Material experimentation is key to her process and her material choices are often significant. “Dusk and Dawn” includes a series of abstracted glass works that calls “glass paintings.” These works are composed in panels and position kiln-fused glass over Ghana-must-go bags—cheap woven nylon totes in plaid patterns that are named after a 1983 decree that forced Ghanian immigrants from Nigeria. The bags themselves have become symbol of global migration and exodus. In these glass paintings, glimpses of the bags are revealed in almost celestial patterns that call to mind ancient forms of navigation and mapping.

Layo Bright, Anacardium occidentalis (Epo cashew) (2019). Photo: Rebecca Ou. Courtesy of the artist.

In other works, Bright adorns her figurative ceramics with gele, West African head ties, which signify beauty and cultural belonging. In the exhibition at the Aldrich, many of the gallery walls, one notices, are painted in undulating gestures of dusty, rose-colored hues; here Bright’s tinted the walls with from Nigerian camwood powder, which is used for skincare treatments. For Bright, working across a range of materials links her to artists she most admires: Simone Leigh, Wangechi Mutu, Fred Wilson, Kara Walker, and Alison Saar.

Layo Bright: Dawn and Dusk (installation view), The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum. Photo: Jason Mandella. Courtesy of the artist.

The exhibition is, in many ways, a celebration of the beauty and strength of Black women. “I’m thinking of portraying Black women in my work in different ways—these are the women and people I am personally inspired by,” she noted. The exhibition takes its name from a pair of sculptures—dusk (2024) and dawn (2021)—which are among the first works to greet visitors in the space. These sculptures each depict the same woman’s face. She wears an ambiguous expression, her cheeks marked with lines reminiscent of scarification traditions. dawn [gold topaz] #3 transitions from a deep a golden hue at its base to fully translucency, its counterpart dusk [sari blue] #3 is a deep nocturnal blue. These two women act as pillars, constant and enduring as the cycles of night and day.

But Bright brings both a sense of fragility and reverence to their experiences as well. Glass is something of an unusual medium in contemporary art, one associated most often with stained glass windows or vessels and vases meant to hold the very flowers Bright turns to glass. In the exhibition, her works from a space of both sanctuary and celebration. In the work, The Thorns and Roses (2022), Bright offers up a working fountain of blown luminous black glass. Black vines and flowers wrap around its curved shapes. The sculpture feels at once mournful and serene. Water, in Nigeria’s Yoruba culture, is an element where life and death intermix. The fountain is positioned in the center of a gallery with Bright’s abstract glass works hanging on the walls nearby. The space is contemplative and offers a moment of stillness and reflection, as the water flows on like time, like life.