Art World

Art Bites: Was Leonardo da Vinci the Original Bird Lady?

Not only did he try to unlock their secrets of flight, he also advocated for their humane treatment.

Leonardo da Vinci was a pioneering painter and inventor—and, perhaps, bird lady. Avians appear in a number of the 13,000 notebook pages he produced, from the kite hawks of Codex Atlanticus (c. 1478) to his comparatively compact folio Codex on the Flight of Birds (c. 1505). It’s easy to attribute the master’s affinity for birds to his longing for the sky, but there’s evidence that he had a particular fondness for our feathered friends.

Studies into Leonardo’s love for animals found that his specific love for birds started in his childhood. In a letter, his patron Giuliano de’ Medici noted he wouldn’t consume animals or allow any harm to be done to them. Vasari famously wrote that Leonardo would buy birds at the market and set them free on the spot. The artist himself recounted that a vulture flew into his crib as a baby and stuck its tail in his mouth. Sigmund Freud later analyzed the anecdote at length.

Left: Leda and the Swan (c. 1504-1506), from the collection of Franz Koenigs, Haarlem, Netherlands; middle: Leda and the Swan (c. 1504-1506), from the collection of the Duke of Devonshire, Chatsworth, England; far right: Study of a Leda (c. 1504), from the collection of the Royal Library, Windsor Castle, Windsor, England. Photo: Art Media/Print Collector/Getty Images.

The earliest inquiries into Leonardo’s notebooks, which began in the 19th century, also led art historian Jean Paul Richter to conclude that the artist was likely a vegetarian. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals recently considered whether he was “the forefather of the animal rights movement.”

Meanwhile, Peter Jakab, a curator at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum, in Washington, D.C., has written that “Leonardo’s interest in flight appears to have stemmed from his extensive work on military technology which he performed in the employ of the Milanese court.” The artist made his first flying machine drawings in the 1480s, while serving as painter and engineer to Milanese duke Ludovico Sforza. Leonardo returned to Florence in 1500, the year after Sforza lost power, then went to Rome to serve as senior military architect and engineer to the son of Pope Alexander VI.

One of Leonardo da Vinci’s flying machines in the Leonardo Da Vinci Museum. Photo: Frank Bienewald/LightRocket via Getty Images.

Around the time he started painting the Mona Lisa, Leonardo was concocting flying machines that consisted almost entirely of winged contraptions called ornithopters. His aerial screw of 1489, an early helicopter, was an exception. But, no matter how Leonardo engineered his winged machines, he couldn’t overcome the human body’s limits. People just can’t keep themselves in the air.

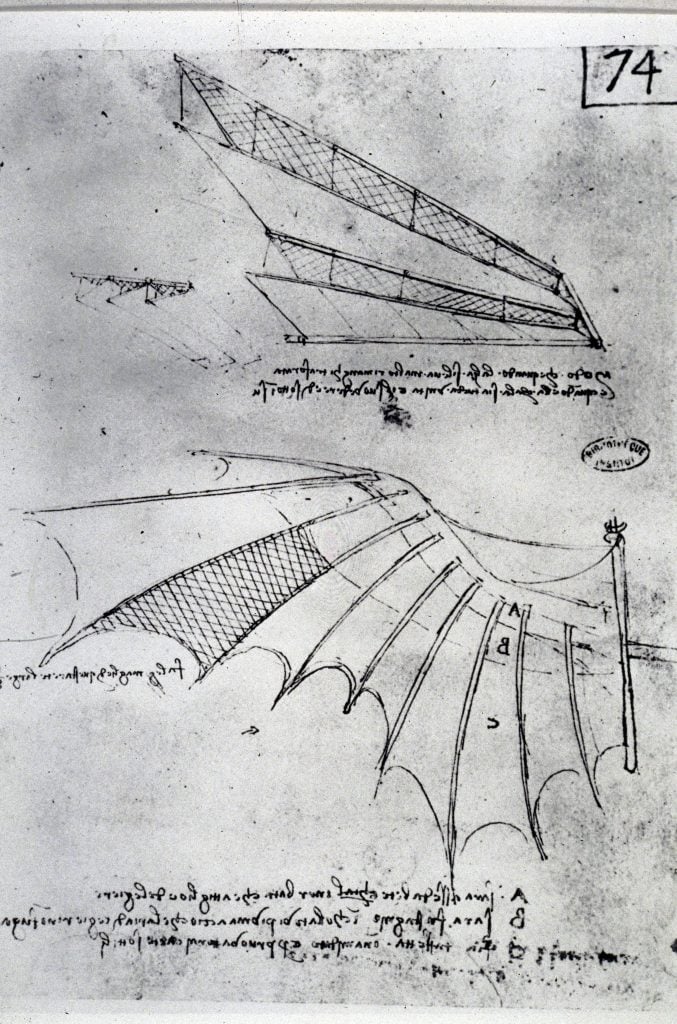

Codex on the Flight of Birds (c. 1505) marked his first foray into studying the way birds really fly—and how their aerodynamism might translate into mechanical flying machines. He had the revelation to focus on suspension rather than propulsion. Later innovators barely heard of his work. Scholars only recently proved that he discovered the principle of dynamic soaring 400 years before Lord Rayleigh did.

Page from the Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex on the Flight of Birds (1505–06). Photo: SSPL/Getty Images.

“A bird is an instrument working according to mathematical law, which instrument it is within the capacity of man to reproduce with all its movements, but not with a corresponding degree of strength, though it is deficient only in the power of maintaining equilibrium,” he wrote in the notebook. “We may therefore say that such an instrument constructed by man is lacking in nothing except the life of the bird, and this life must needs be supplied from that of man.”

While he loved the birds for their closeness to the sky, Leonardo also loved the birds themselves.

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history. These delightful nuggets shed light on the lives of famed artists and decode their practices, while adding new layers of intrigue to celebrated masterpieces.