Art & Exhibitions

Lee Krasner Had to Fight Her Way Into the History Books. Here are 5 of the Biggest Battles She Faced

On the occasion of a Krasner show at the Barbican Art Gallery, we look back on how she fought her way to attention.

On the occasion of a Krasner show at the Barbican Art Gallery, we look back on how she fought her way to attention.

Javier Pes

Lee Krasner had to wage all kinds of battles in her life. To be taken seriously as an artist and pioneer of Abstract Expressionism, she had to confront the chauvinism of the New York art world. Then there were anti-semitism, ageism, and the mixed blessing of being “Mrs Jackson Pollock.”

But as her friend, the playwright Edward Albee, learned, she was not one to mess with. “She looked you straight in the eye, and you dared not flinch,” he said at her memorial service. During a visit to Krasner’s studio by the playwright Tennessee Williams and the painter Fritz Bultman in 1940, the two men noticed a line by the poet Rimbaud inscribed on a wall. After they criticized the translation, she kicked them both out.

That formidable determination comes across in the bold canvases she painted, some of which are enormous.

“There is a real force to a lot of her work that really struck me when I visited museum collections internationally,” says curator Eleanor Nairne, who brought together nearly 100 Krasner works for a touring exhibition titled “Lee Krasner: Living Color,” which opens at London’s Barbican Art Gallery on May 30. The exhibition is accompanied by a publication, which Nairne has edited, and the first European edition of Gail Levin’s biography of the artist. Both of the new books are published by Thames & Hudson.

To mark the exhibition and publications, here are five key battles Krasner had to fight to get the attention she deserved.

Jackson Pollock and Lee Kranser in Pollock’s studio (1950). Photo: Lawrence Larkin for the New York. Courtesy American Contemporary Art Gallery, Munich.

Throughout her life and career—and certainly after Jackson Pollock’s death—Krasner was fiercely protective of his legacy. “She was very open about speaking about [Pollock’s] influence on her, and about her influence on him,” Nairne says. “She believed in him as a great American artist and she believed in herself.”

But in the 1950s, others, including fellow artist Barnett Newman, saw things differently. When he telephoned to invite Pollock to sign an open letter protesting the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s “contempt” towards avant-garde art, Lee answered the call, only for Newman to ignore her and ask to speak to her husband. Lee was also excluded from the famous Life magazine group portrait of the other signatories, who were together nicknamed the “Irascibles.”

Yet in the macho days of the 1940s and ’50s, Krasner had to pick her battles. “I couldn’t run out and do a one-woman job on the sexist aspects of the art world, continue my painting, and stay in the role I was in as Mrs. Pollock,” she told the art critic Cindy Nemser. That role included coping with his her husband’s self-destructive alcoholism, artistic self-doubts, and affairs—all the while promoting his work.

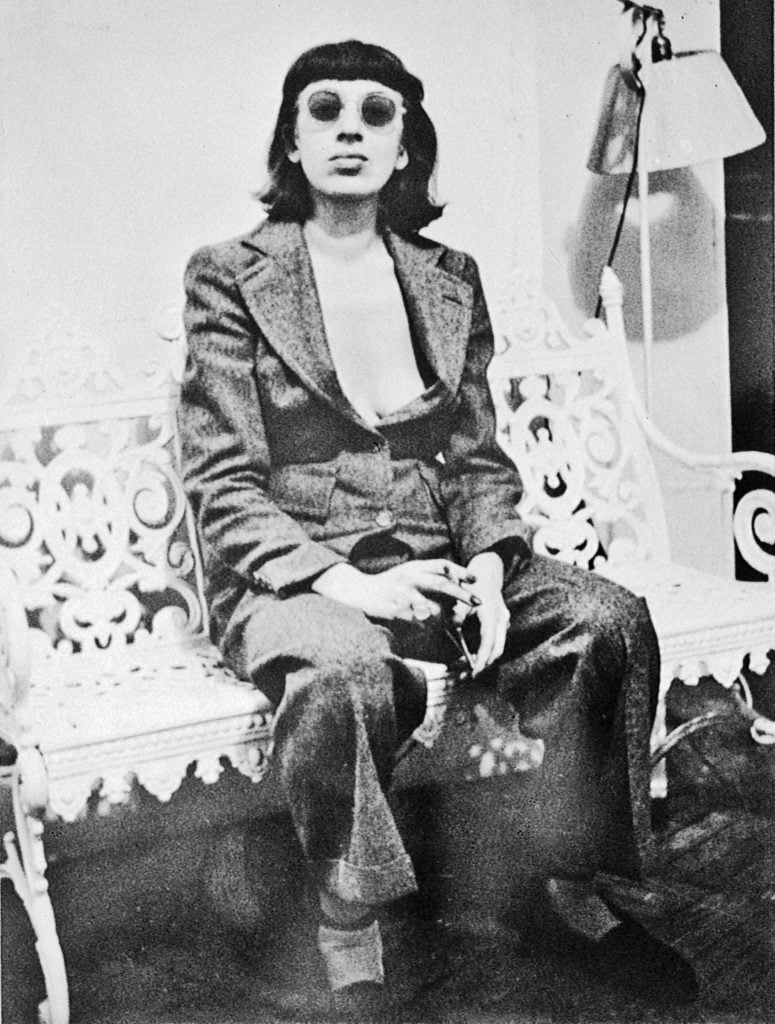

Lee Krasner around 1938. Photographer unknown.

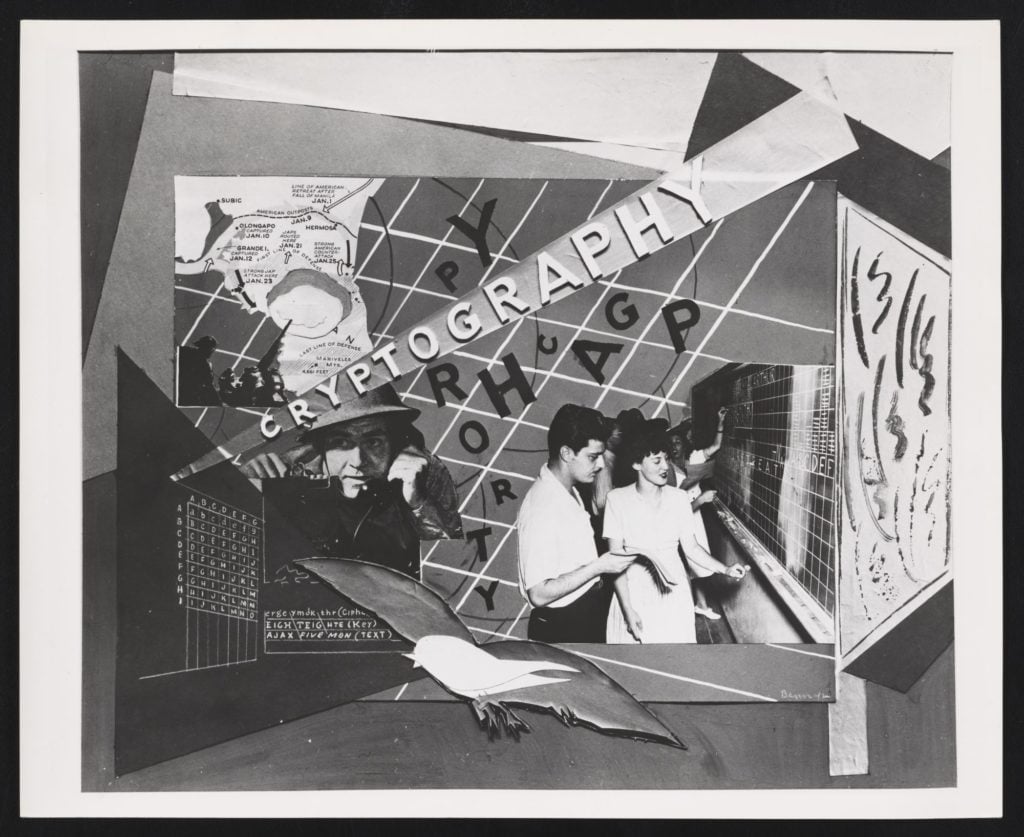

By the time she met Pollock, Krasner was an established artist and a veteran of the Works Progress Administration’s program to commission artists to create large-scale public works. During World War II, she supervised the production of 19 shop window displays in New York to promote the war effort. The artworks advertized courses in fields from cryptography to explosive chemistry through collage and montage imagery as striking as anything ever produced by the Bauhaus.

Krasner threw herself into the research, not letting her dyslexia stop her. She also recruited eight artists, whom she called “her misfits,” to complete the work. Two of them were Pollock and Willem de Kooning. The original designs are lost, but documentary photographs survive and form a surprise highlight of the Barbican show.

“We found them in the Archives of American art, so we’ll project them on the same scale as the window displays,” Nairne says. Nevertheless, for most male American artists—particularly ones influenced by chauvinistic European Surrealists—women were treated like dolls to be dressed up. “I was considered a ‘dame’ even if I was a painter too,” Krasner recalled.

Photograph of design for War Service Window Displays, 1942. Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

As the daughter of Jewish-Russian immigrants, Krasner was wary of anything called “American art.” In her biography, Levin points out that as a young artist in the 1930s, Krasner knew all about Thomas Hart Benton’s claims that the “true American experience” could never be painted by migrants, leftists, or Jews.

Born Lena, Krasner adopted the less ethnically specific name Lenore as a teenager, which she shortened to the more androgynous Lee as early as 1930. At the height of the Cold War, the FBI opened a file on Krasner, under the names “Mrs Jackson Pollock” and “Lee Pollock,” and suspected her of being a spy. Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb were also investigated. All three were Jewish.

Peggy Guggenheim photographed for Look magazine in 1966. Photo: by Tony Vaccaro.

In 1945, Pollock famously signed a contract with patron Peggy Guggenheim to give her most of his output in return for a $2,000 loan towards the down payment on a rundown house and adjacent barn in Springs, a small town in East Hampton. When the price of Pollock’s work began to rise in the 1960s thanks to Krasner’s energetic promotion and stubborn refusal to sell cheaply, Guggenheim took the artist’s estate to court. Krasner prevailed after a lengthy legal battle, and Guggenheim’s claim for works she alleged were painted in 1946 and 1947 was dismissed.

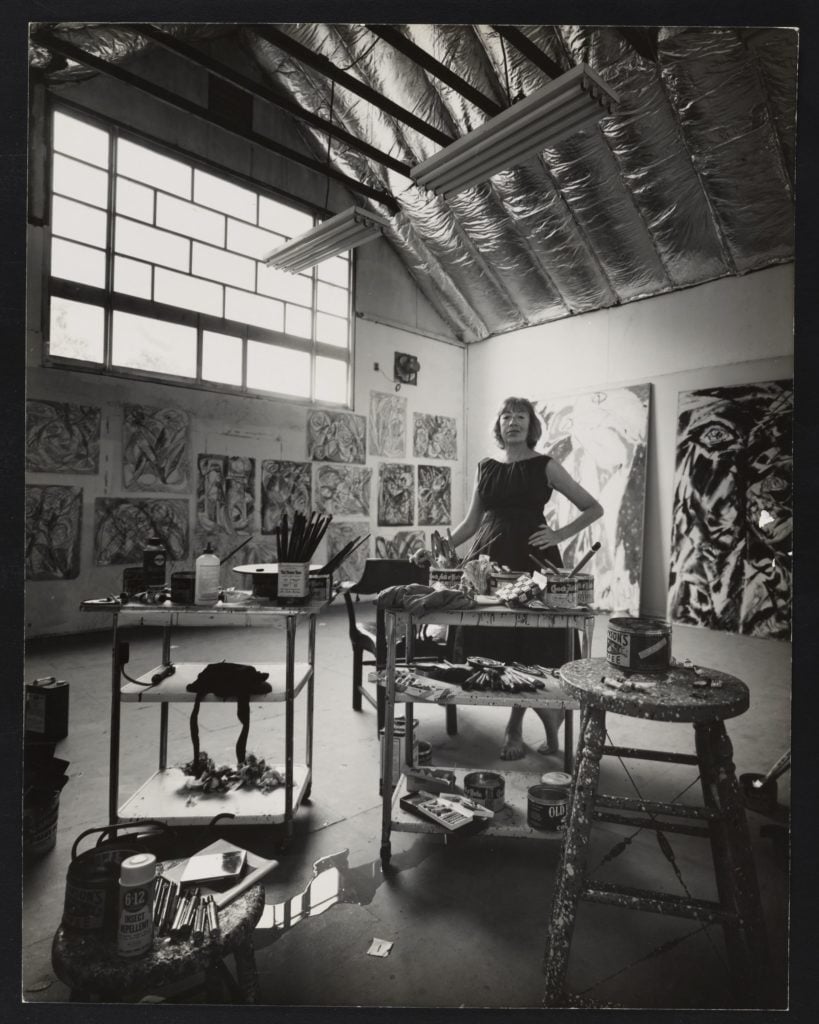

Lee Krasner in her studio in Springs, 1962. Photograph by Hans Namuth. Lee Krasner Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

While Pollock worked in the couple’s barn in Springs, Krasner had to use a bedroom in their house as her studio, and also had to make her own furniture. She only moved her studio to an outbuilding six years later, and it was not until 1957—a year after Pollock’s death in a car crash—that she took over his old studio in the barn.

“There was no point in letting it stand empty,” she said. For the first time, she could enjoy its excellent light and space, and the scale and ambition of her work increased.

Lee Krasner, Another Storm (1963). Private Collection © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation, Courtesy Kasmin Gallery, New York.

Krasner enjoyed her first major solo museum show at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 1965. By the time of her major US retrospective (which opened in Houston on her 75th birthday in 1983 before ending at the Museum of Modern Art in New York after her death), her achievements as an artist were finally being acknowledged.

Importantly, Krasner always cared that her works would last beyond her lifetime. “Pollock was using house paint, but she adamantly refused to go down that path, even when they were penniless,” Nairne says. “She refused to work with anything other than oil paint and she spent any money she had on quality cotton-duck canvas.”

Many of her works are being exhibited in Europe for the first time during the Barbican exhibition’s tour. The painting that traveled the furthest is Combat (1965), which is more than 13 feet long. The work is coming from the National Gallery of Victoria in Australia and has had “a very long journey,” Nairne says—just like the artist.

The exhibition is organized by the Barbican Art Gallery in collaboration with Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Zentrum Paul Klee Bern, and the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao.

“Lee Krasner: Living Colors,” May 30 through September 1, Barbican Art Gallery, London.