By the early 2000s, the mega dealers were pulling far ahead of smaller galleries in a market growing with astonishing speed. All four megas were privately held and published no financial statements detailing revenues, expenses, profits, and losses. Even their corporate statuses were unclear. Still, soundings could be taken from art fair sales wrap-ups, when mega dealers broadcast their triumphs, and from the auction houses, where works sold by the mega dealers and their clients sometimes went for multiples of their retail prices. Overall, the total art market in 2002 was $21.151 billion. In 2008, it would grow to more than $62 billion, nearly tripling in volume. These were the years in which Larry Gagosian became the best-known art dealer in the world, his gallery’s growth paralleling the growth of the art market.

With that growth came a new degree of brazenness on many dealers’ parts for luring away artists from rival dealers. A case in point came in December 2003, with the very popular John Currin, whose figurative paintings seemed plucked from the Renaissance, though not without a satirical edge. Andrea Rosen, a midsize dealer, had nurtured his career from 1991, with slowly but steadily rising prices. She had just celebrated the launch of a three-city retrospective, from Chicago to London to New York, when news broke of the 41-year-old’s jump to Gagosian. Artists went from dealer to dealer, but to do so in the artist’s hometown at the end of the tour?

Gagosian was amused by how much ink, as he put it, the New York Times gave to the news, but irked by a quote from David Zwirner, who called Currin’s move “a real shock” and added that “our generation doesn’t have that aggressive behavior.” That was “fucking bullshit,” as Gagosian later put it. “Everyone operates about the same way. To take the high road, or burnish his ethics on my hide—it pissed me off. If the tables were turned, he’d do the same thing. Why try to come off so PC?” No one, he added, had a gun to the head of any artist. “In my experience, it starts with you hearing the artist isn’t happy. In extreme cases, you have a gallery that’s not paying the artist. That’s less likely with a good artist. But it can happen. Or the artist and dealer have just had a falling out. If it’s an artist you like, you pay attention. That’s how I got John Currin.”

Zwirner might feel his generation was different, but he was doing his share of poaching too. “David has actively poached artists,” sniffed one Chelsea dealer. “True, it’s common. But he will court an artist in a certain way. And it’s hypercompetitive.” So it went with Lisa Yuskavage, whose sexually suggestive portraits of women had found an eager market through her shows at the Marianne Boesky Gallery.

Between Yuskavage and her dealer, success had bred tension. “Lisa was going to leave no matter what,” Boesky admitted later of Yuskavage. The artist’s rise had left her critical of Boesky’s “context,” as dealers and artists put it: the other artists at the gallery. She wanted Boesky to kick out certain artists, just as Betty Parsons’s artists had wanted her to do decades ago. Boesky thought of altering the context by taking on artists Yuskavage might like, but how could she be sure the new ones would satisfy Yuskavage in the long run? Still, Boesky was hurt and embarrassed when Yuskavage went with Zwirner. The departure of Japanese artist Takashi Murakami for Gagosian was even more painful, coming as it did after nearly a decade of steering his career from obscurity and widespread rejection to global acceptance.

Murakami had perfected the style he called superflat. As in a Walt Disney animation cell, there was no visual depth, no brushstrokes or evident human imperfections. Boesky had first become aware of Murakami through a small but plucky gallery called Feature Inc., from which Boesky had poached him. Galerie Perrotin in Paris would also play a role with Murakami. But credit for building his career in the United States went mostly to Boesky and a pair of laid-back Santa Monica dealers, Jeff Poe and Tim Blum, whose story said a lot about how the contemporary art market took off.

Poe was the quiet, even taciturn, one, Blum the upbeat salesman. They had started with a small gallery in Santa Monica in 1994 and found themselves struggling to get by. They had one unusual card to play, and so, in desperation, they played it. Tim Blum had become fascinated with Japan in his twenties, enough to live there for four years, learn the language, fall in love with contemporary Japanese art, and work in a Tokyo gallery. Both Blum and Poe were particularly drawn to the then-unknown Murakami. They began to exhibit his work in 1997 and became his Los Angeles dealers. Boesky became his New York dealer, first including him in a group show in 1998, then giving him a solo show the next year.

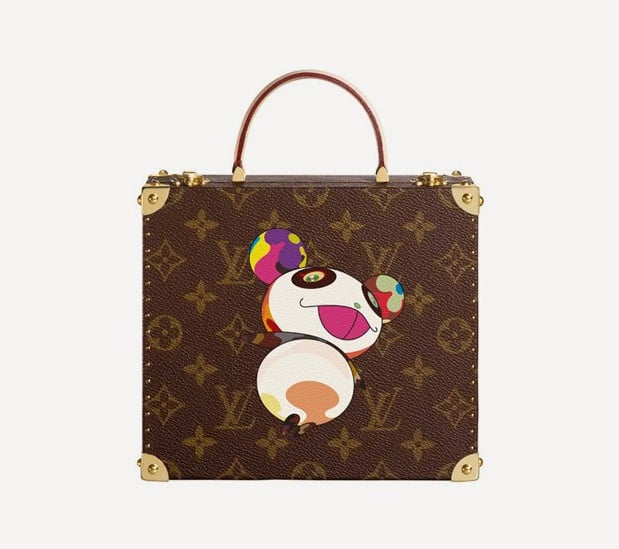

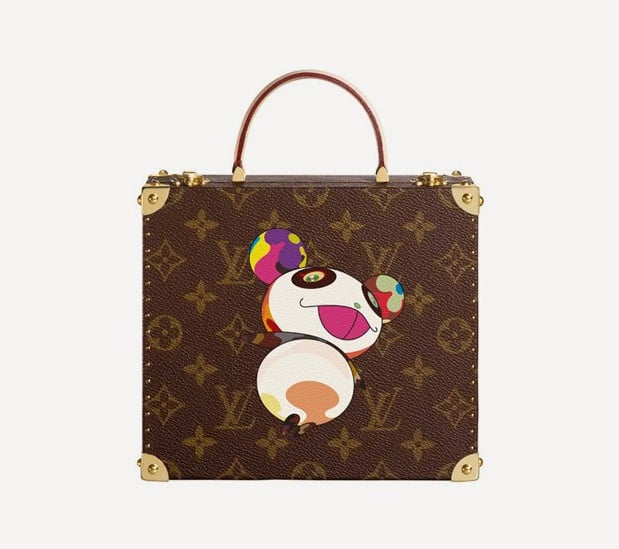

Takashi Murakami bag for Louis Vuitton. Photo: Louis Vuitton.

In 1999, Blum & Poe first showed Murakami at Art Basel: 10 paintings, surrounding a sculpture of mushrooms with a typical Murakami character beside them. “We were looked at as complete idiots by the rest of the fair,” Poe later admitted. “Superflat wasn’t there yet; we were ushering into Western history an Eastern history that had been excluded.”

Murakami had fabricated those first works at his own expense. In 2001, as his reputation grew, he opened a production space in Japan and began hiring dozens of workers. Clearly influenced by Warhol, he worked in both fine art and commercial art, blurring the line between the two. Ultimately, he wanted to make everything from paintings to scarves to keychains, all with his Murakami brand. In 2003, Murakami also embarked on a handbag partnership with designer Marc Jacobs of the fashion brand Louis Vuitton. The handbags were a huge hit.

By now, Murakami had begun asking his dealers to underwrite production costs—not for Vuitton bags, but for much of the rest of his work. Blum and Poe knew that Murakami was no spendthrift. He slept in a converted crate in his office, just outside Tokyo, and worked every waking hour, making all design decisions, no matter how small.

The problem was his ambition: it was just so sweeping. They underwrote as much as they could, as did the artist’s other dealers, but when Murakami announced that his next project would be a 19-foot-high platinum and aluminum Buddha, his dealers balked. Boesky was pregnant in 2006, and Murakami, she recalled, didn’t like the timing of that at all. “You’re lactating, you can’t be my business partner,” she recalled him saying.

After ten years on Boesky’s roster, Murakami severed relations with her and signed with Gagosian as his New York dealer. Blum & Poe stayed in as Murakami’s LA gallery, going so far as to charter a plane from Japan to bring the still-unfinished Buddha to the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art (LA MOCA), where it would be shown as part of a Murakami retrospective. They also bought $50,000 worth of tickets for the opening night gala and provided a six-figure contribution to help finance the show itself. Even more was needed, so Gagosian and Murakami’s Paris dealer, Perrotin, kicked in. And so did Boesky.

Boesky could accept that Murakami would leave her for Gagosian. What galled her was LA MOCA’s subsequent request to borrow key Murakami works that she owned, followed by Murakami’s reaction. As soon as her Murakami paintings were hung on LA MOCA’s walls, the artist stopped communicating with her. “Murakami is a fucking genius,” Boesky said later. “I hate him, but he’s a genius. What I hate is the way he left—without honor.”

Tim Blum and Takashi Murakami in 2013 in Los Angeles. Photo by Stefanie Keenan/Getty Images for Blum and Poe.

It was not by chance that a paradigm-shifting artist like Murakami was shown at LA MOCA. Nor was the Blum & Poe gallery situated in Santa Monica because its partners preferred sunny California to New York City. For dealers like Blum and Poe, the West Coast was no longer as arid an art scene as it had once been. A new chapter in contemporary art was opening in LA, and it had a lot more to do with the art being made than dealers poaching each other’s artists.

LA’s recent history had begun, in a sense, in 1979, with the opening of LA MOCA that year. At last, the city had the makings of an art center—and one founded by artists, at that. Four years later, the Geffen Contemporary at MOCA added 40,000 square feet of exhibition space in LA’s Little Tokyo historic district. MOCA director Richard Koshalek made a brilliant move in 1984, purchasing part of Count Giuseppe Panza’s historic collection of Abstract Expressionist and Pop art. Trustees groaned at the $11 million price; soon they would realize the purchase had made MOCA one of the world’s top museums of contemporary art—for a song.

With those arrivals, gradually more galleries opened in half a dozen neighborhoods. Richard Kuhlenschmidt opened a basement space on Wilshire Boulevard and made a point of showing challenging art, much of it conceptually based and from the Pictures Generation. Daniel Weinberg brought New York artists to the West Coast, among them Jeff Koons, Robert Gober, Sol LeWitt, and Bruce Nauman. There was no core area until galleries began congregating in West Hollywood, on the Beverly Hills border. Then, in the early 1990s, Santa Monica became the core. Kuhlenschmidt came. So did Weinberg. From New York and Europe came an early international gallery partnership: Luhring Augustine and Max Hetzler. Yet another new gallery in Santa Monica was Blum & Poe.

For Rosamund Felsen, one of LA’s longest-lived dealers, who had opened her first gallery in 1978, the move to Santa Monica from West Hollywood was bittersweet. One after another artist left her, culminating in the departures of Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelley. McCarthy explained that he was about to start making major, expensively fabricated works, financed by his new global gallery, Hauser & Wirth. “Then Mike Kelley came in…. He needed to leave too,” Felsen rued. “All the artists that he had been seen in context with were no longer there.” Santa Monica had grown, but at a cost for small and midsize dealers.

Irving Blum wasn’t surprised. The affable pioneering Warhol dealer had had his own struggles in the LA market, first in the 1960s with the Ferus Gallery, then in 1986, when he gave LA another go with his New York gallery partner, Joe Helman. He was soon reminded why he had left LA in the first place. “The Los Angeles scene is always two steps forward, one step back,” Blum said. “It’s needed some centrality, and Santa Monica has provided it. But the truth is, it hasn’t happened yet that LA has become a major art center. With thirty or so galleries, there just isn’t the density that New York has. Everything seems to be focused here now, and that’s great. But the ongoing problem is that collectors will still only spend up to a certain level. When they want to spend more, they go to New York. That’s what makes the situation ultimately provincial.”

Mark Grotjahn. Photo: Stefanie Keenan/Getty Images for Blum & Poe.

Blum and Poe were set on proving the skeptics wrong. From their tiny gallery in Santa Monica, they had an outsize influence on artists as far away as Murakami in Japan and as close to home as Mark Grotjahn in LA. Grotjahn started as a shy aspiring artist who came to the gallery to see other artists’ work. By the time Blum and Poe met him in the mid-1990s, he had been struggling for nearly a decade to find his way. When his world looked bleak, he went on drinking binges. With a friend, Brent Peterson, he opened a small gallery named Room 702 in Hollywood and started working with other artists. The conversation, at least, helped. To earn money for his family he played Texas Hold’em for serious stakes.

As an artist, Grotjahn was struggling without success to find his own style—to the point that in 1993 he started painting the handmade store signs he saw in his neighborhood. Many of the signs, as critic Jerry Saltz later noted, were for dives and quick marts, burger joints and newsstands—and liquor stores, lots of liquor stores. “I deduce someone scared, strange, on the margins, avoiding big, glitzy stores,” Saltz speculated, “invoking a hardscrabble, old-school Raymond Chandler vibe, an almost alcoholic loner.”

True or not, Grotjahn felt that the signs he’d copied weren’t as good as the originals, so he went to the store owners and asked to exchange them. Most agreed, since as far as they were concerned the signs were the same. The sign chapter taught Grotjahn a lot about line and color. It also pulled him out of his cafard. By 1998, he was painting in a new way he liked.

“Mark used to come to the gallery,” Poe recalled, “and see every show and talk to us.” He never showed work of his own. “One time we said, ‘Why don’t you bring in some drawings?’” Grotjahn did, and Poe gave them a look but was unimpressed. Out of politeness, and because Grotjahn was a nice guy, Poe agreed to visit his studio to see more. Poe saw a different body of work there, one that really intrigued him. Grotjahn was doing what looked like landscapes, with what seemed to be rays beaming out from a setting sun. The artist called them two-tiered perspective paintings. Later, they would be known as his butterfly paintings.

Grotjahn’s paintings in his first show at Blum & Poe in 1998 failed to sell. At a second show two years later, Grotjahn sold exactly one, for $1,750. He called the experience a “whipping.” Sometime after that, he bought two large stretched canvases that some other artist had ordered from a vendor but failed to pick up and let them lead him to a new approach. The first of them he painted as one of his horizontal, two-tiered perspective works. After studying the finished painting, he decided he didn’t like its orientation. So he shifted it on the wall from horizontal to vertical. He liked how it looked—enough to make his second canvas vertical from the start. The vertical perspectives looked intriguing and fresh: not sunsets but vortexes. At a third solo Blum & Poe show, in 2002, Grotjahn’s latest paintings stirred growing excitement.

Don Marron, the financier/collector who would soon add Grotjahn to his collection, saw a lot of artists with their dealers. This was a relationship that stood out. “Grotjahn with Blum and Poe is one of the great examples of how steadfast commitment to an artist you believe in can yield tremendous results—rather than seeing how they do for a year and then dumping them. It was real commitment, like Leo [Castelli] and [Jasper] Johns, and like Ellsworth Kelly and Brice Marden with Matthew Marks.” Ironically, Grotjahn would later be one of the first artists of his generation to have multiple dealers—four in his case—and call his own shots.

Thomas Houseago. Photo: Instagram/@simondepury

LA’s art scene was on the map, but not just because of new galleries and museums. The California Institute of the Arts, founded in 1961 and known as CalArts, had lured a whole generation of future artists and dealers. Some of its teachers were well-known artists. Several had participated in Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the 1990s, a groundbreaking 1992 show in which 16 artists explored alienation, dispossession, perversity, sex, and violence. Among the curious drawn to LA by that show was David Kordansky, an aspiring artist and dealer who came west from Connecticut. He was fired up by the vision of learning from his heroes—Paul McCarthy, Mike Kelley, and the ultimate mentor, Conceptual artist John Baldessari—and set on being a dealer of contemporary art that mattered.

Kordansky arrived at CalArts to find a seismic shift underway. A number of teachers, led by Baldessari, had left CalArts for UCLA or the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena. “It was no longer about the monastery up in Valencia,” as Kordansky put it. Teachers and students were challenging CalArts’ rigor and tradition, where professors mercilessly critiqued students’ work and sent them off in tears. At UCLA and the ArtCenter, students were artists even if they never picked up a paint brush. As CalArts lost its allure, there were fewer painters to be found there either.

Upon graduating in 2003, Kordansky, with a partner, Ivan Golinko, opened his first gallery at 510 Bernard Street, a tiny cul-de-sac in Chinatown. The gallery had a mission: to take on CalArts artists and in so doing promote painting, which CalArts had de-emphasized, and help restore the school’s luster. One of Kordansky’s first artists to achieve a high level of success was Jonas Wood, a friend who assisted Kordansky’s wife, Mindy, herself a sculptor. Wood was becoming known for his portraits of friends. In 2019, he would still be a Kordansky artist, though by then he would be a Gagosian artist as well.

Another of Kordansky’s early finds was the British-born Thomas Houseago, whose outsize sculptures, in bronze among other materials, sometimes depicted figures, sometimes abstractions, and often featured exposed rebar, giving a sense of incompletion. The artist and his dealer became fast friends. “We were young and dumb and were partaking in pretty reckless behavior,” Kordansky readily admitted. “There was an explosive and intoxicating energy between us.” Only one solo show, and one group show, had come out of their alliance by 2005. But Kordansky felt sure that would change in 2008, when he moved to a larger gallery in Culver City. A first Houseago show in the new space came and went—and so, to Kordansky’s shock, did Houseago. “I put my heart and soul into him,” the dealer recounted, still hurt years later, “and he ends up leaving me.” For Kordansky, a career-making artist was gone, a friendship torn asunder. “I was 31,” he recalled. “It was the greatest life blessing.” Like Zwirner after Franz West’s shocking departure, Kordansky saw he needed to grow—to not focus on any single artist, but instead promote all his artists equally.

[…]

A Richard Prince nurse painting. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

In 2003, Gagosian was named by ArtReview as the figure who had had the most impact on contemporary art’s value and reputation. He would stay at or near the top of every such annual list from then on. Jackie Blum, wife of dealer Irving Blum, suggested that Gagosian’s brilliant strategy was to live rich before he got rich—to have the fancy Hamptons house and the plane before he could afford them and therefore start socializing with the very rich who would become his clients. Rivals conceded Gagosian’s dominance but still rolled their eyes. “Why do you deal with him?” a Christie’s staffer asked a collector at lunch one day. The collector sighed. “It’s . . . Larry, I don’t know, it’s Larry. I know he’s a rogue but he’s offering me the best stuff.” Others winced at perceived slights from the lord of the realm. “Larry will say hello to me if I’m with someone he wants to meet,” observed one dealer. “In the elevator, if it’s just the two of us, he’ll barely say hello.” Along with the half-dozen or so largest collectors from the previous two decades, a new generation of Gagosian collectors had come aboard. One was real-estate developer and art investor Aby Rosen, another was hedge-fund manager David Ganek, and a third was television producer Bill Bell Jr., a keen Koons collector with his wife Maria Arena. The parties Gagosian threw for these collectors were lavish but, for their host, obligatory. The truth, suggested one observer, was that Gagosian didn’t much enjoy his own parties. “He shows up for fifteen minutes, then leaves unless [Microsoft billionaire] Paul Allen shows up. Larry is great at this. He is unavailable—and then suddenly he is available. He knows how to play it. But he’s not that interested in people as people.” One of Gagosian’s great gets in this period was artist Richard Prince, who had gone from Metro Pictures to Barbara Gladstone. In the mid-2000s, Prince’s Nurse paintings, with their images of nurses taken from 1950s paperback covers, reportedly struck Gagosian as “curator art,” reported the Wall Street Journal. He wasn’t the only one: Arne Glimcher declared that Prince didn’t have a touch. “They’re mildly interesting as book covers—photographing art on art,” Glimcher acknowledged. “But how big was that idea?”

Still, as the artist’s market rose, Gagosian began taking an interest. He was seen socializing with Prince—affecting plaid shirts as Prince did. The turning point was a major Prince show at the Guggenheim. Despite Gladstone’s help in making it happen, the artist’s mind seemed set. He left, as Gladstone noted, right after the Guggenheim show.

Clearly, money figured into the decision. According to the Observer, Gagosian granted Prince a generous sixty-forty split on all sales, with the greater share going to the artist. He also put a Prince on pretty much every one of his collectors’ walls. At Gladstone, Prince’s Nurse paintings had sold in the low six figures. In July 2008, a painting from 2002, titled Overseas Nurse, sold for a record $8.4 million at Sotheby’s, indicative of what Gagosian was doing with his primary work to goose the market. It was the start of a hugely lucrative run for Prince and Gagosian, but one that would be tested by lawsuits brought against Prince and the Gagosian gallery by photographers indignant at Prince’s appropriation of their work for his own.

A sculpture by Donald Judd. Image courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Powerful and wealthy as he was, outpacing all his rivals, Gagosian was not generally regarded as the most adventurous of the mega dealers. Neither was Glimcher. Hauser & Wirth was still feeling its way. Zwirner at this time was the one taking the most chances on edgier artists. A decade or so after signing up his first primary artists, nearly all remained with him, their stars still on the rise, including political painter Luc Tuymans, site-specific installation artist Diana Thater, socially satirical pen-and-ink illustrator Ray Pettibon, and Stan Douglas, the noirish filmmaker.

As if taking on a sideline hobby, Zwirner had also signed up several of the Minimalists and Conceptualists who had made their names in the 1960s and 1970s only to be preempted by the splashy Neo-Expressionists of the 1980s. Most were dead, so signing them up meant working with their estates. Abstract painter Ad Reinhardt, with his monochrome black paintings, was one; he had died in 1967. Fred Sandback, who died in 2003, was a Minimalist/Conceptualist sculptor who had worked with yarn, stretching single strands from floor to ceiling at geometric angles that created sculptural volume.

Minimalism was very much New York based, which left out another Zwirner acquisition, California artist John McCracken, though he, too, worked with simple geometric shapes. McCracken, still living when Zwirner took him on, was best known for his leaning, highly polished planks, somewhere between surfboards and the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey. He worked with lacquer, fiberglass, and plywood, ending up with sleek, brightly colored forms that earned him and a few of his West Coast fellow artists the classification of “finish fetishists,” a term he rejected. McCracken was sort of a stoner and believed in the existence of aliens, with whom he said he had had encounters. With McCracken’s death in 2011, Zwirner started working with his estate too.

The most prized of the 10 or so estates Zwirner had, though, was clearly Donald Judd’s. Judd was the acknowledged father of Minimalism, known for his stacked boxes and his extensive writings on the philosophy of art. He had denied that his works were sculptures, preferring to call them “specific objects.” He had also denied that he was a Minimalist, yet the term would stick to his work. Drawn to the sweep and solitude of western landscapes, Judd had traveled extensively through the Southwest, developing desert-based architectural projects. The town of Marfa, Texas, was where he came to rest. Judd created the Chinati Foundation, which showed works by fellow artists John Chamberlain, Dan Flavin, Carl Andre, and Claes Oldenburg, among others. Over time, the foundation came to maintain 70 square miles of undisturbed ranchland.

Zwirner had barely opened his first gallery when Judd died in 1994, at 65. The artist’s works began to rise in value, to the point that in 2013, one of his large-scale sculptures would sell at auction for $14,165,000. That was an all-time high for an esoteric work from 1963; as of 2018, only seven of Judd’s works would have been sold for over $5 million at auction. Still, Judd was clearly a dealer’s prize. Pace represented him for 20 years, both before and after his death, but after a last solo show with Pace in 2011, Judd’s estate moved to Zwirner.

With this Minimalist lineup, Zwirner struck many as the true successor to Leo Castelli. One dealer conceded that Zwirner had, as he put it, “very much of a European tilt to what he’s doing. Gagosian would have hot artists, artists that collectors bought because they thought they’d make money on them. David is a little more cerebral, a little more subtle.”

[…]

Art Basel Miami Beach did more than bring dealers and collectors together for three days of art talk and fun. It pushed prices of hot artists ever higher, as did its precursor, Art Basel. “One day Mark Grotjahn was an artist making a living,” Schiff noted. “The next, all his work is being sold at auction.” Grotjahn’s butterfly paintings were soaring higher than almost anyone else’s work. “He went from five thousand dollars to five hundred thousand,” Schiff rued. “It was at the beginning of this new phase of short-term profits in contemporary art. ‘Let’s dump our butterfly paintings!’ became the rallying cry. I did too,” Schiff sighed. “It was the dumbest thing I’ve ever done but I was scared. All that upswing for your clients. You couldn’t afford not to sell.”

Josh Smith, Peter Brant, and Urs Fischer. Photo: Clint Spaulding/Patrick McMullan.

[…]

The megas weren’t the only dealers having banner years in the mid-2000s. Gavin Brown was backing new and promising young artists, and doing well by them too. He had Conceptual artists like Martin Creed, famous for a piece that consisted of lights being switched off and on. One light switch, one room. That was the work.

One of Brown’s closest artist pals was Urs Fischer, who tested their friendship with a Conceptual work in 2007. One day while Brown was elsewhere, Fischer showed up at his gallery with a work crew toting drills. In short order, the workers jackhammered a deep wide hole, removing earth and debris with a backhoe, in the gallery floor. The process of making the 38-by-30-foot crater was the art.

“I never saw it fresh,” Brown recalled later with a shrug. “But I wasn’t surprised.”

The earth work, titled You, earned lots of critical attention, most of it positive—the more so when Brown sold it to collector Peter Brant. What exactly was Brant buying? “He bought the energy,” Brown said. “He maintained his position in front. Then he went and dug a hole in his own place.”

“It was an environmental piece that could be reproduced,” Brant explained later, “and I reproduced it for an Urs Fischer show. One of our galleries had the hole dug up.” It could be reproduced again—as often, it seemed, as Brant liked.

Brown admitted the whole exercise was a bit crazy. “I think it shows a kind of insanity,” he agreed. “He knew that, the artist knew that, we all knew that. I think we’re in an insane age. I guess you either get on that train or walk to another destination.”

“What’s it worth?” Brant echoed when asked about the value of his pit. “I don’t know. Probably nothing. But it’s an important piece of our history.”

Excerpted from Boom: Mad Money, Mega Dealers, and the Rise of Contemporary Art by Michael Shnayerson. Copyright © 2019. Available from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.