People

‘Nothing Was Ever Out of Bounds’: Leigh Bowery’s Friends Remember the Legendary Performance Art Provocateur 25 Years After His Death

Cerith Wyn Evans, Baillie Walsh, and Lou Stoppard reminisce about their late friend.

Cerith Wyn Evans, Baillie Walsh, and Lou Stoppard reminisce about their late friend.

Lou Stoppard

Artist Cerith Wyn Evans and director Baillie Walsh met Leigh Bowery on the London club scene. To both, he became a collaborator and a close friend—a subject to film, a designer to call on for incredible garments, an artist to admire, a conspirator to talk with for endless hours on the phone. Sometimes he helped them, sometimes they helped him. Always, they recall, he pushed them—not necessarily forward, that would be too expected, but in a new, uncertain direction that was wide, warped, strange, sweeping, and beyond anything they’d planned. Walsh’s collaborations with Bowery include the music video to accompany Boy George’s 1991 song “Generations of Love,” Massive Attack’s “Unfinished Symphony” video from 1991, as well as “Unstitched” from 1990, which shows Bowery having his cheeks pierced and was regularly screened as a backdrop to Bowery’s performances. Wyn Evans’s works with Bowery include the early films Epiphany, from 1984, and Degrees of Blindness, from 1988. Here, they reflect on their late friend with Lou Stoppard.

Cerith Wyn Evans: Baillie, do you remember he had a tattoo on his inner lip that read “mum?” It was facing inwards so that only his teeth or throat would read “mum.” I told him, If he pulled his lip down, to everyone else it read “wuw.” He said, “Yer – wooo!”

Baillie Walsh: I’ve never talked about Leigh before. It was all too close at the time.

CWE: For a while, it felt like there was a load of people who wanted a bit of it all. When someone died and there was too much attention or discussion, Leigh used to say, “Oh, they just want another slice of death pie, so they can look like they have been a part of something.” And knowing what we do know, that he was living and dealing with HIV, those comments mean more.

BW: My relationship with Leigh was private, special, and personal. I didn’t want it to be public property. But now, 20 years have passed—longer, 23 years—I don’t get the same feeling. It’s nice to see how much I remember, together with Cerith, we can see if we can wheedle out some memories—and some laughs hopefully as Leigh was a-laugh-a-minute. I would like to remember more. What I loved about him was how he’d just turned everything on its head. He made you think in a different way. The idea of “fitting in” was abhorrent to him. I want to remember that. I often try to think in the way that Leigh pushed me to, and it’s nice to have a refresher course.

Bustier with hand-sewn crystals by Leigh Bowery, early 1990s. Courtesy of Lorcan O’Neill.

Lou Stoppard: One thing written a lot about Leigh Bowery is that his whole life was a performance, a work of art. Would you agree with that, having known him more intimately?

CWE: Well, it’s yes and no. I always thought he was much more extreme in mufti, or daywear, than he was in the outfits that he wore at night.

BW: That was much more disturbing, I agree. He looked like a child molester.

CWE: There was a vulnerable side to him, which you saw if you were a close friend. He tended to keep his friends apart; he didn’t like the idea of us talking about him. We had to be kept compartmentalized.

BW: He did love to cause trouble. He loved making stories up. He loved to lie. He would tell you someone had died. He once told me that Brad Branson was dead—he is now dead, so I can tell this story. He told me he was dead because Brad had slept with my boyfriend, John Maybury, so he thought I’d like to hear that. He told it to everybody.

CWE: He absolutely adored lying. I remember him telling me a story about Les Child, who was a dancer with the Michael Clark Company, how he was going through hard times—the company had got dissolved, or was on a break, or something like that. He said, “Oh poor Les. He’s making sandwiches in a gay sauna in Soho.” And I said, “Oh you bitch.” I was laughing. It was obviously a total lie. But then two months later, I ran into Les in the street who said, “I’ve taken to making sandwiches in a gay sauna in Soho. I’ll spring back.” It was true! So you never knew.

BW: Leigh loved to muddy the waters. You never knew what was true and what wasn’t.

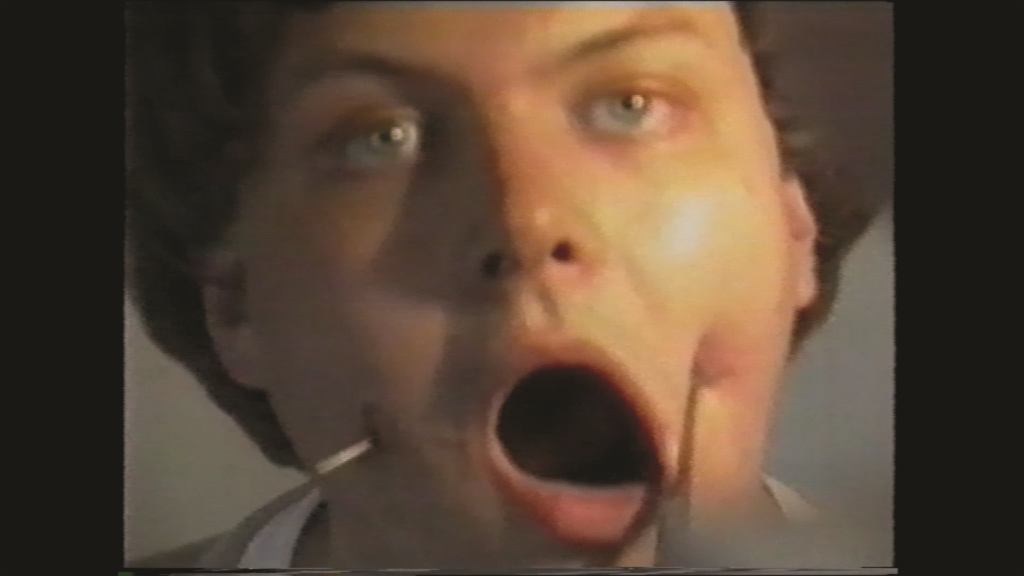

Still from Cerith Wyn Evans, EPIPHANY (1984). Courtesy of the British Film Institute National Archive.

LS: Can you both recall when you first met him?

BW: I can remember my first vision of Leigh. It was him and Trojan in Heaven nightclub in the “Pakis from Outer Space” blue look. Apart from the look, they seemed very shy and almost demure. It wasn’t an immediate friendship. It took time. Really, I got to know Leigh properly because I started working with him. I took him to Italy to be in a fashion show—and it was that thing of going away with people and becoming friends, him, Big Sue. He made papier-mâché head masks of himself with the drip look he used to do. So, he had 30 models come out as him. It was for a company called Calugi e Giannelli—really tacky, but we’d do anything for a fee in those days, and it meant going away with a crowd. It was over times like that that I got to know him as him.

CWE: I met him around the same time at The Bell, a gay club in King’s Cross. We used to go on a Sunday night. I nearly fell over because Leigh and Trojan walked in, and Trojan was dressed as Sheba with really intense turquoise hands and face. That look—”Pakis from Outer Space”—was like Leigh’s collection at the time. I was a student at the Royal College, it would have been around 1983. I thought: “I’ve got to do something with these people, I wonder if they’ll be in a film.” I went up to them: “Oh hello, I’m a film student at the Royal College, would you ever consider making a film?” They said, “Yes all right then. We’re going to be in a film!” Leigh really took it seriously. Suitcases would arrive with makeup. Consummate professionals, from the word “go.” And they would do anything. The film was Epiphany. We shot the whole thing on tape on huge machines that had been given by the BBC to the Royal College. You had reels of two-inch video tape—the quality was insane. But these cameras were huge and so heavy, big pneumatic things with enormous cables that would almost move around on their own. We had three cameras on Leigh at all times. He said, “Which camera should I look at? The one with the red light?” And I said, “The red light is going to be on all of them; we’re recording everything, no takes.” He just loved that atmosphere—constantly being watched, reinventing himself, and rethinking his position. You know when you see the cliché of a model or David Hemmings pretending to be David Bailey—Give me this! Give me that! Leigh was like that. Going from look to look, posing and moving. It was just heavenly to witness. It was raw. There was a levity to it. But also, there was a sense of stagecraft and something studied—it was deeply sincere, however much of a laugh it was. The pain he went through and the discomfort to get the looks. It was an exuberant celebration on so many levels.

BW: He never thought he had a look unless it was painful. If it was painful, it meant he was taking it further than anyone else would. One night, we went to Heaven when he was doing the “Mexican mask” look and wanted his profile to be as flat as possible so you didn’t get any nose. I had to take him out because he had a complete panic attack, which you rarely saw with Leigh. He was in proper, incredible pain. You couldn’t unzip the mask because it was so tight. His voice was muffled, and his face was squashed: “Get me out of this!” I took him and Nicola Bateman back to my flat, and I got pliers and scissors to try to undo the zip. I couldn’t get them into it because it was so tight against the skin. Somehow in the end, he got out of it.

CWE: There would be bruises. He would be cut to shreds after a night out.

BW: Each time he went out, he wanted to push it further, getting more and more ambitious. There were some looks he would test out and never do again. He would always gauge the response. If he was just laughed at then that was a disaster. There had to be something more thought-provoking than that. It had to be challenging.

LS: What did he want people to feel? Disgusted? Scared?

BW: Both of those things. He liked laughter too—but not just laughter.

CWE: He was physically so very strong, and often he’d be on insanely high shoes. He was so massive. One of the things he liked doing at Taboo was kicking the ceiling lights out—bang! Glass in everyone’s drinks.

BW: His behavior at times was so extreme. He would pogo around the dance floor—he was such a large being, so it was really intimidating, especially as he was dressed in such a way, with the merkin on and something covering his face. But it was never aggression in a typical sense.

CWE: Never angry.

BW: No, I don’t think I ever saw Leigh angry.

LS: Was he a private person in some ways? Is that part of the reason he performed so much with his own identity, in order to keep certain things hidden?

BW: Well he kept his HIV status from me.

CWE: Me too.

BW: That was obviously very private. But I never felt that Leigh kept secrets much from me, which was why I was so surprised when I did find out that he was HIV positive. That was such a massive thing, especially at that time, because there was nothing you could do.

CWE: Fear and paranoia was everywhere.

BW: We were all watching hundreds of people die around us. When you watched someone die, you were not only very sad you were also terrified—Is that going to be me next? I think Leigh felt that very strongly. I think Leigh didn’t want to be labelled as someone with AIDS. Leigh was much more important, much more than that. And I think that if he had announced that, and if it had gone out into the world, he wouldn’t have been given the freedom to be other than that.

CWE: You look back and think: “Why didn’t I see it?” It was so obvious. We formed a band for a while, me, Leigh and Angus Cook, who was my boyfriend at the time. We didn’t play any music. We were called Magpie Shmagpie. Sue Tilley took the press photographs, which we did on the stairs of the sexual health clinic on Dean Street: all of us coming out of the door, posing with jackets on our shoulders—Leigh’s idea, obviously.

BW: He would talk about it hypothetically: “What if? What am I going to do if I’ve got AIDS?” But everyone was saying the same thing. We lived in fear.

CWE: I remember him on his deathbed saying: “I didn’t even bloody lose any weight.”

LS: I’ve heard he started rumors when he knew he was dying that he was going off to live in a different country.

CWE: He’d say he was going to Papua New Guinea to research anthropological tribe masks. After he died, we went to Patisserie Valerie and spent about 200 quid on cream cakes and had champagne. Sue Tilley said no one was allowed to cry.

Still from Cerith Wyn Evans, EPIPHANY (1984). Courtesy of the British Film Institute National Archive.

LS: I wonder what he would do if he was alive now. Because to play with your identity is easier now than ever, with all these different platforms.

CWE: So many years have passed—it’s a different world. The implications of what Leigh started off doing, and his ways of communicating about things, have become so mainstream, in a way.

BW: Leigh would have morphed into something else. There were so many different stages he went through during my friendship with him: he started in the clubs with no idea of entering the art world; he wasn’t creating art; he was creating attention for himself. Then that ambition changed when he got the gig with Anthony d’Offay gallery, and then later he met Lucian Freud through you, Cerith.

CWE: We sort of thought, “Oh it’ll be fun to mess things up for Lucian—we’ll introduce you to Leigh and then you’ll have to paint sequins!”

BW: I feel that Lucian’s work did change after he met Leigh. Part of Leigh’s thrill was always challenging his friends, and of course he did that to Lucian. I think you can see Leigh’s influence in those pictures.

CWE: Absolutely you can. Lucian was hugely affected by Leigh’s death. He was so so close to him, he really looked up to him.

BW: I love the fact that Lucian still looked up to him even after they found a stolen picture of his in Leigh’s flat. Leigh was stealing 50 pound notes every day when he went in there.

CWE: Lucian would think that that was just wonderful. He would think it was the most noble thing to do!

BW: They deserved each other. These two really strange characters coming together—it was a match made in heaven.

LS: Baillie, talk to me about working with Leigh on your films.

BW: My favorite project was the “Generations of Love” video with everyone in the street. Leigh just loved being a hooker on the street.

CWE: With the blonde wig and the “Come to Bed” t-shirt.

BW: Leigh was the one who got me thinking: “Oh, it’s a pop video, but I can make a porn video.” It was Leigh’s influence on me that kind of pushed me the whole time. He was a great doer, always with massive enthusiasm. It was a great collaboration. We just did it. He loved getting everyone in character and in dress. He’d be pushing Sue: “Get your tits out!” He got everyone—Rachel Auburn, Les Child, Michael Costiff, Talulah—in their costumes and their appropriate looks. Les Child fought every step of the way because Leigh was trying to cover his face in Vaseline. I would say that that was our most successful collaboration. His influence pushed me to a place that I thought was really interesting for a pop video.

CWE: That video is sort of sad also in a funny way. It’s mournful. There’s a melancholy at the heart of it, this idea of generations of love.

BW: I think the last project we did together was the Massive Attack video. That shoot was the first and only argument I ever had with him, and I don’t think he ever really forgave me. He’d made a dress for Shara Nelson, and we needed to find some way to cover up the earpiece that we needed her to wear. The collar wasn’t high enough, so he suggested a wig. She looked ghastly in, but of course Leigh loved it because it was so wrong. It got very awkward in front of the band. Leigh was determined, and I had to finally put my foot down. Leigh never really wanted to be told what to do. We were never quite the same after that trip to LA. Before that, we’d been two hours on the phone to each other everyday for seven years. But then also our lives were changing. Leigh was working with Lucian—his interests were changing. Our common interests were drifting.

CWE: He’d never do what he was asked to. At that time, I did some pop videos for The Fall. And we also did a play together at Riverside Studios where he played a Chicago mafia boss. Leigh would improvise lines, and every night he would stretch his lines by quite a few minutes by writing some “new material.” I can remember him coming on doing dances or singing songs, and then going into his lines. Mark E Smith would be grumbling and laughing. One thing that has always stuck with me and has been a barometer for me ever since: Leigh would look at something and say, “Yer, it was all right. But where’s the poison?”

Almost like a kind of homeopathic thing; you would need this poisonous kernel, so that it could be transformative, something in it that was deeply subversive and could dissolve hierarchies.

BW: Exactly. As much as he did work for me, I also did a lot of work for him. He would engage you as the magician’s helper. One of my strongest memories of him is when he did the AIDS benefit at the Fridge. It was his first ‘douche’ show. He comes out dancing with a corset and a merkin. I think it was to ‘Nothing Compares to You’. He’d rehearsed it so he’d lie back on a plinth, open his legs, and squirt a fountain of water from his arse. But he hadn’t rehearsed it with a corset. So, when the time came, he couldn’t lean back. So he goes to the front of the stage and bends over to squirt over the white table cloths. Of course, he was very nervous so the water wasn’t completely clean. He’s squirting shit all over the front row of an AIDS benefit. For the second part of the piece, he put a great big skirt on that I had to get under (as I was the back of the horse, if you will). I’m meant to get him onto my shoulders so he could be ten feet tall waving in this giant skirt. I get under and it’s covered in shit, slipping around everywhere. But it’s show business—not a choice! He was properly freaked out after that show; he knew that he had pushed the poison to the limit as people were horrified. And it did cause a scandal. He’d shat on the front tables at an AIDS benefit! That was Leigh when he really did think for a minute that he’d pushed it too far. There was fear—and it was rare that you saw Leigh with fear.

CWE: If you did that now, you’d probably go to prison. Anything that was inappropriate—Leigh was like a magnet. Everything inappropriate was good. Everything appropriate was bad. It was pretty clear cut. He was really an anarchist.

BW: That’s why John Waters’s films so influenced Leigh. Divine in Female Trouble was a benchmark for Leigh in so many ways.

Still from Cerith Wyn Evans, EPIPHANY (1984). Courtesy of the British Film Institute National Archive.

LS: Was it ever tiring being friends with someone who was that unrelenting in their commitment to subversion?

CWE: No. Because he was also so sweet and gentle. Like Baillie described—I was one of the people on the other end of the phone for an hour or two a day. We’d sit there watching television and he’d be like—What is Lorraine Kelly wearing?

LS: Did you ever feel embarrassed by him?

CWE: I can remember being on holiday in Cornwall with Leigh. Sue Tilley drove Leigh down; she couldn’t get into the car because Leigh had made a frock to wear in pink dayglo. It was like a Molly Goddard dress but the size of a flat—with all this tulle bunched into the car, the entire car was full. As soon as he arrived, he ran into the sea, and it soaked up so much seawater he nearly drowned. It was completely hysterical. I can remember this one dreadful situation: Leigh would do anything to embarrass Sue in public—it was one of his absolutely favorite things to do. So, we were alone in this grand Catholic church. And this lone nun was walking towards us in her habit. Sue was going, “Leigh, no. No. No.” Sue—she’s a big girl—and she’s trying to hide behind the column in the church. And Leigh is going at this 90-year-old woman in her habit, “Oi! My friend wants to eat you out!” The nun just shuffled away. “Bless you my child.” The strange thing is it never wore you out. He was like quicksilver, also. In the next moment, it would be a completely different thing—he’d be helping you make a pea soup. He thought it was hilarious that you had to buy a huge sack of peas to make a small bowl of pea soup.

BW: I was never embarrassed by Leigh because Leigh was never embarrassed. The joke was never on Leigh; he was making the joke, so there was never painful embarrassment.

CWE: But there would be times when he would be vulnerable. He’d open up on the phone and say, “Oh, I don’t know what I’m doing.” He wasn’t always high octane.

BW: Leigh really led a life on the telephone. Cerith was part of that. I was part of that. Sue was part of that. A lot of our lives were spent on the phone—hours and hours a day. That’s not high octane or a performance. That’s a proper relationship.

CWE: You’d talk about things in the news…

BW: …or sometimes there was just silence. And you’d hear a sewing machine going.

LS: The construction of his garments was incredible. People often talk about how great he was at making looks, but perhaps not enough focus is put on just how skilled he was at making clothes.

CWE: He was very fastidious about the idea of learning techniques. He really looked up to Mr. Pearl, who had this career in Paris making amazing corsets. Berwick Street market was an Aladdin’s cave, where you could get the sequin fabrics and needles and threads—he would refer to that as the Stitch Bitch Trail.

LS: He’s often remembered in terms of the Club Kids. What do you make of that?

CWE: I don’t think he actually liked the whole New York Club Kids thing. He went there, he was adored there. But the people that he really liked were the ones from Jackie 60 and Mother and Blacklips Performance Cult. He liked the drag queens who were politicized.

BW: He liked the ones who were incredibly smart. He loved intelligence.

CWE: He liked revolutionary people. Political people.

BW: The Club Kids thing was an early part of his history, but his ambitions moved way beyond that. Leigh, above everything else, was incredibly intelligent, a thing that shines through for me. He had many stages. He created this persona from nowhere. And he trod unknown ground and was still reinventing every day.

CWE: And he was constantly looking for ways to undermine his reputation for what he’d become known as.

LS: Are there any particular days with him that stand out?

BW: It was his birthday, and I really wanted to fuck him over. So I thought: “I’m going to get him a cat. It’s a wicked present to give someone.” I called all the pet shops, and there was a kitten in Camden Town. So I went to the pet shop, and it had sold! I thought: “Fuck it, I’ve failed.” And as I was walking down to St Martin’s Lane through Cecil Court, there was a homeless person with a cat, saying: “Do you want a cat?” I was so shocked I said, “No,” and walked up the street. But then I thought: “Of course you fucking do.” So, I went back and bought the cat, a fully-grown black cat. It was so extraordinary and immediately friendly and affectionate. I went home and put it in a stereo box, wrapped it up and went over to Leigh’s flat. Leigh unwrapped it, saw the box and thought that I had bought him a stereo. He was saying, “Oh that’s great.” Then he opened it, and the cat jumped out. He was completely horrified at first. But then he was a great father to the cat. Leigh adored Angus.

CWE: He named him Angus, which was the name of my boyfriend at the time. He did it to punish him.

BW: The cat was always sleeping in amongst fabric.

CWE: The flat was pretty amazing. Before Trojan died, it had Star Trek wallpaper. And after he died, Leigh decided that he wanted to change it. And as he was peeling off the wallpaper, he found one of Trojan’s hairs, from when Trojan and Leigh had put up the wallpaper. Leigh said he freaked out and didn’t know what to do. “I just ate it,” he said. He just had to ingest it.

LS: Tell me about his wedding; he married Nicola Bateman.

CWE: That was quite late on. I was his best man.

BW: The wedding was one of the secrets that I didn’t know about. Cerith was privy to that. But that was another of those “What else didn’t I know?” moments.

CWE: Leigh was in Minty [his band] at that time. He was also very scared at that point, and I imagine was probably showing symptoms of HIV/AIDS. He got married so that if the worst happened, at least Nicola would have a roof over her head. He was in a furious mood all day. He had this blond wig on and a coat that he’d bought on Brick Lane that was very nice, black, heavy, silk satin—an Orthodox Jewish man’s coat. Nicola just kept saying things like, “Oh darling, this is the happiest day of any woman’s life.” She was dressed in blue and had a blue garter—everything was her “something blue.” She’d really gone for things as if it was the Royal Wedding. Her sister was the bridesmaid and was dressed in a bizarre 1960s pop-art Paco Rabanne dress; her hair was big and bouffant and had black and white make up, mod shoes and big Perspex earrings. After the wedding, Leigh said he had to go to a Minty rehearsal: “Nicola you have the money, make sure that you spend it all on a wedding breakfast.” We went to the Angus Steak House on Leicester Square, the three of us there looking like complete freaks. We had steak and chips and a salad. After, Nicola’s sister and I went to a party at the Architectural Association, where I was teaching at the time—I actually got Leigh in to teach there too—and she won a prize for best fancy dress.

BW: How long before he died did they have the wedding?

CWE: A couple of months. It was the summer, I think, and he died in winter.

BW: On New Year’s. So very Leigh to ruin New Year’s. So sick, because every New Year’s you think of Leigh.

Film still from Baillie Walsh’s UNSTITCHED (1990). Courtesy of the artist.

LS: Tell me about getting him in to teach at the Architectural Association.

CWE: I was teaching a foundation course, which I’d got into because someone had asked me to come show my films and give a talk to some students. I’d asked to see the students’ work and ended up doing these tutorials and got on well with the students. Someone was having a baby and went on maternity leave—so all of sudden I was running the foundation department at the Architectural Association, despite having never studied architecture and actually being rather suspicious of architects. I ended up teaching there for seven years. I’d try and get them to look at things around buildings: dance, fashion, the body, do plans for zoning in department stores, or map Selfridges on top of the British museum so the Assyrian department would be in the same place as the shoe department—stuff like that. It was about opening people’s minds up, to stop them just thinking about making fabulous houses on golf courses in the Mediterranean. I thought Leigh would be perfect to come in, do it for a term and see how it went. I had a bit of a budget, so we hired ten sewing machines. He suggested we have to make a pair of gloves, as that was really, really difficult. So, we did a glove making workshop—every student had to make a pair to fit their own hand, and Leigh was there to help. The students were just over the moon—they loved him. On his first day, he had been so nervous. I remember he had on this pair of trousers that Jean Paul Gaultier had given him. They were green stretch satin, the weirdest thing. They had obviously worn out so many on the bottom that they had the overlocked stitching to hold them together, over and over and over again to keep the whole thing together. I can remember looking at him; he was covered in makeup—very, very heavy foundation.

BW: It would be orange.

CWE: And lots of rouging on the cheeks. Sometimes he’d wear one of his chemotherapy wigs, which he would have gotten from a charity shop and then cut so you could see all the netting on the scalp. But he was so tall. I thought: ‘You’re huge today, four inches taller than normal.’ I couldn’t work it out. He lifted the trousers up. And inside his trainers was a pair of trannie stilettos.

BW: He loved height. He wanted to be the biggest man in the room.

CWE: He was so nervous though.

BW: But the nervousness was endearing, wasn’t it?

CWE: Absolutely. By the end of the day he knew the names of their brothers and sisters, where they came from, all of that. He’d see them two months later and be like, “So, is Mathilda still doing the veterinary college thing?”

BW: There was always a boy he really fancied.

CWE: One time, Pearl came in, and we showed them a VHS cassette of a Christian Lacroix couture show. The students had never seen a fashion show. Pearl was there whispering away about couture and handcraft with his 16-inch waist. Leigh thought the show was genius and flawless. All the students were really getting into it. So, the project developed so that at the end of Leigh’s term we were going to do a fashion show, where the models were going to be the students and they were going to make outfits, couture outfits, based on a building. A very bright boy from Bulgaria chose a Bruce Goff strange kind of desert range house from the early 1960s. There was a very privileged Iranian woman who didn’t have a portfolio and would use a brand-new giant Chanel shopping bag to carry her work. Leigh was of course like, ‘She’s a genius; she’s incredible.’ She decided that for the fashion show, she wanted to come as the Taj Mahal. So Leigh helped her make a papier-mâché dome helmet, which she decided she was going to cover in fusilli pasta, glued on and sprayed silver. Now, the Taj Mahal has a lake down the front of it, so she got some Perspex manufacturer to make these two narrow strips which went down the front with blue colored water inside and model trees glued down the side. The fashion show was very well attended—Vivienne Westwood, Rifat Özbek, Jasper Conran, and people from Vogue came. Leigh was the compere. And for that role, he decided to sport his head coming out of a toilet bowl with brown latex filled with rice krispies all down his front—like a brown shitty head coming out of a toilet—with a see-through corset, a huge skirt and black eye makeup. He had a clipboard with notes about each student and spoke in a voice as if it was a couture show: “And the next model that we have is…” I remember in one bit he said, “Dana has come at the Taj Ma Hole, oh sorry Mahal.” People were roaring with laughter. It was off-the-charts mental what people were wearing, but the students were genuinely moved.

LS: The breadth of the things you both worked with him on is quite something: films, teaching, performances.

CWE: Well, he was a very creative person, so nothing was ever out of bounds.

BW: It’s been lovely reminiscing and remembering. The tragedy is that he’s not here, because he would be pushing boundaries like no one else I’ve ever known and making me, certainly, and probably everyone else question everything.