Politics

Collector Leonard Lauder on How Vintage Postcards Can Help Us Understand Propaganda in the Present

As an exhibition of his postcard collection opens at MFA Boston, the storied collector explains what draws him to these diminutive works.

As an exhibition of his postcard collection opens at MFA Boston, the storied collector explains what draws him to these diminutive works.

Menachem Wecker

Leonard Lauder was first drawn to postcards as a boarding school student in Miami Beach. Lauder, the 85-year-old chairman emeritus of the Estée Lauder Companies, especially loved the ones that area Art Deco hotels doled out for free, with images of sand extending uninterrupted for miles.

In reality, “it wasn’t really on a wide-open beach. There were hotels on either side,” Lauder told artnet News in a recent interview. “But there you were with the hotel sitting on the empty beach, with the sea in the background and sand all around. It was sort of a fantasy for me.” The color palettes also moved him. “I don’t like the many shades of gray,” he said. “I like colors.”

Lauder’s boarding school friends also collected the freebies, but only for a couple of years. Lauder, however, stuck to collecting. Before long, he was buying 100-year-old postcards from a stamp dealership.

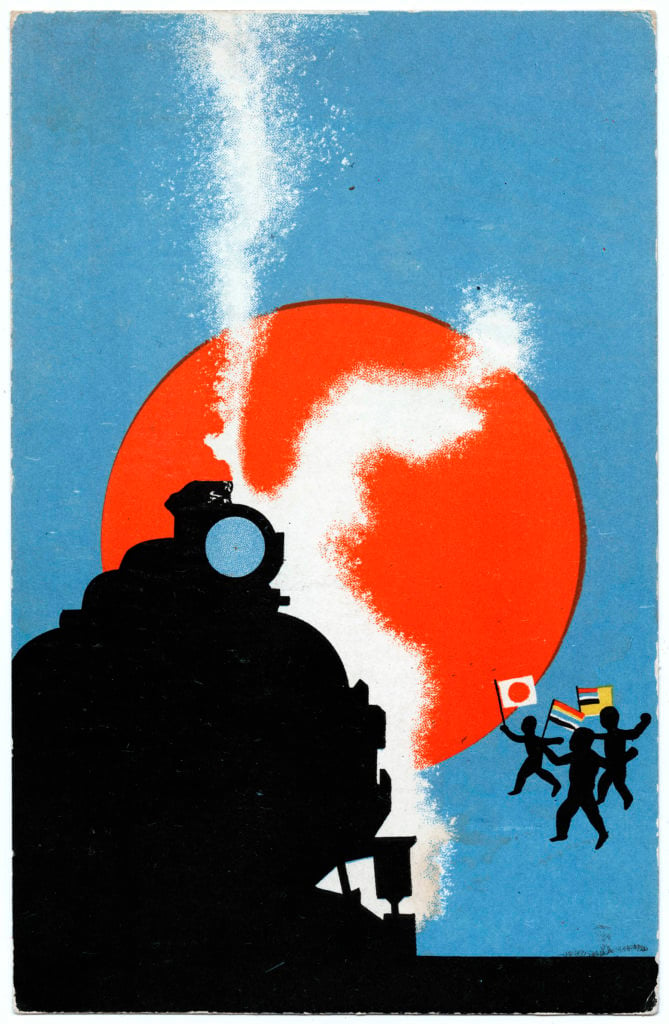

The Southern Manchuria Railway train greeted by children weaving national flags. Color lithograph on card stock. Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive. Promised gift of Leonard A. Lauder. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Today, he owns about 130,000 postcards. Much of the collection is a promised gift to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Many of the cards produced between World War I and the end of World War II have strong propagandist content, and 350 of these are the subject of a new volume and an exhibition at the MFA, Boston titled “The Art of Influence: Propaganda Postcards from the Era of World Wars” (through January 21).

The Allure of Cards

In elementary and high school in New York, Lauder became deeply interested in postcards, which were a cheaper way to communicate than the telephone. “There’d be a card that would say, ‘See you at lunch today.’ If you mailed a card before nine in the morning, it was delivered before noon,” he said. “This was the email of the day.”

It was no surprise that these popular and easily transferable cards became enlisted in war efforts and propagandist machinery. An avid reader, the young Lauder came to see postcards as “living history.” He would go through flea markets and find real photo postcards, an early form of citizen photojournalism created with technology that allowed people to develop photos very quickly as postcards.

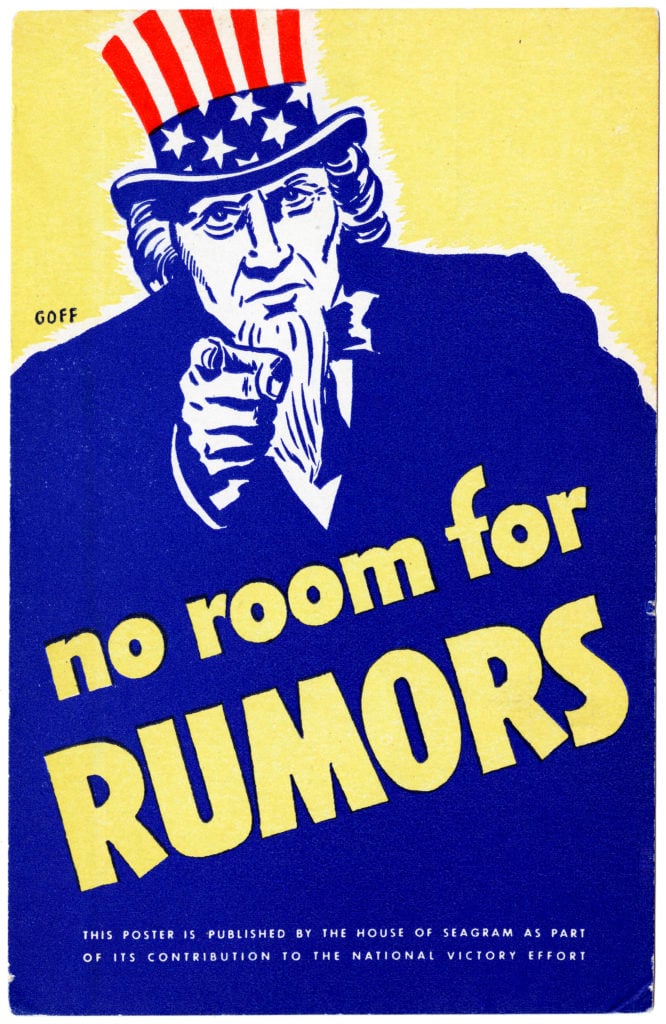

No room for RUMORS (English caption). Color lithograph on card stock. Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive. Promised gift of Leonard A. Lauder. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

“I saw things like the assassination of the archduke in Sarajevo in 1914, and later on, the killing of Mussolini when they hung him up by his feet in northern Italy,” Lauder recalled. “No one knew what they were looking at. I did. That gave me even more pleasure.”

As his collection grew, Lauder kept the postcards in shoe boxes—“Is there any other way?”—though family and friends failed to grasp the appeal. “They considered me odd, but I’ve always been odd,” he said. “I don’t consider that an insult, but a compliment.”

In the propagandist postcards, Lauder saw the skills of artists emerge in ways that he hadn’t in the images of Miami Beach hotels. He often found himself poring over cards that Nazis created and disseminated to spread their ideology.

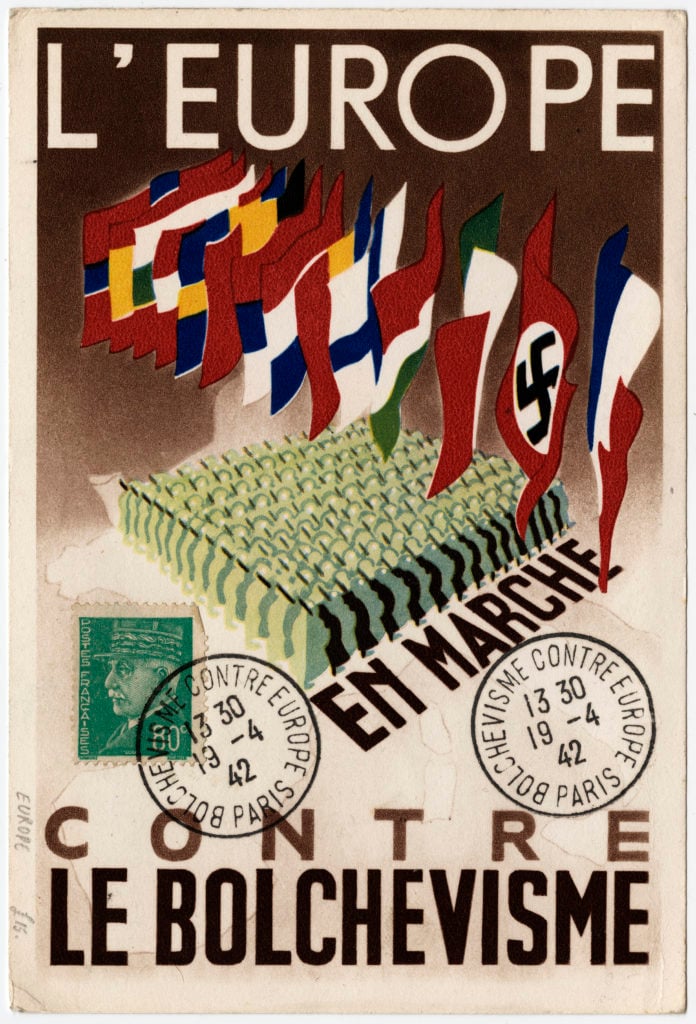

In one reproduced in the MFA’s new book, an abstracted mass of two-toned, green soldiers marches under a row of flags, including a Nazi and a French flag. The caption of the card, issued around 1942 by the puppet Vichy government, reads in French, “Europe marches against Bolshevism.” It accompanied an anti-Communist exhibit in the French hall Salle Wagram.

Europe on the Move against Bolshevism (French caption). Color lithograph on card stock. Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive. Promised gift of Leonard A. Lauder. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

“There is Europe marching against Bolshevism, and there is the French flag flying and the Nazi flag flying, and all of the other flags of conquered nations flying, saying we’re all together in fighting the Communists, or Bolsheviks,” Lauder said. “It was a particularly striking card to me, because it was issued by the French with a Nazi propaganda point of view.”

Although he is Jewish, Lauder didn’t think there was anything wrong with collecting cards issued by the Nazis for their artistry and historical importance. In fact, the cards taught him how easy it can be to fall prey to a dangerous message.

“If you look at the imagery today, you would say, ‘How could they have been duped by it?’ But they were,” he noted. “What drove me to do this book was that most people did not realize the banality of the propaganda and how effective it was. That was… the Facebook of the time.”

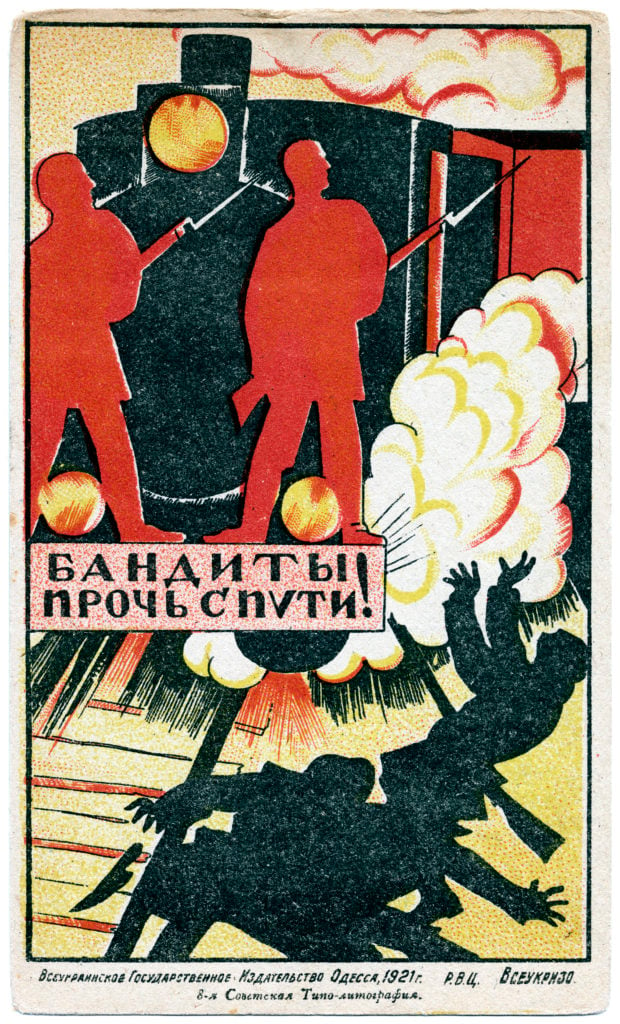

Bandits, Get out of the way! (Russian caption). Color lithograph on card stock. Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive. Promised gift of Leonard A. Lauder. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Postcards were among several art forms used for propagandist purposes, according to Sara Duke, curator of popular and applied graphic art at the Library of Congress. “Because they were intended to be mailed, they were naturally easier to disseminate than posters and political cartoons,” she said. “Whether they demeaned African Americans or Jews, lambasted suffragettes, or belittled wartime enemies, postcard propaganda flourished from the late-19th to the mid-20th century.”

Governments and artists saw in postcards a way to disseminate visual imagery that could express opinions and rally citizens around common causes inexpensively and effectively. Commercial publishers also capitalized on the technology, which was an important correspondence tool for soldiers, according to Duke. After World War I broke out, five million postcards were sent to the battlefront daily; 3.5 million a day came back.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries were a ripe time for postcards to emerge. “It is the same time period in which scraps for scrap-booking, commercially produced valentines, and the poster enter onto the scene,” explained Femke Speelberg, the associate curator of prints and drawings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. “All of these forms have roots in older media, but the industrial revolution created these objects of mass appeal.”

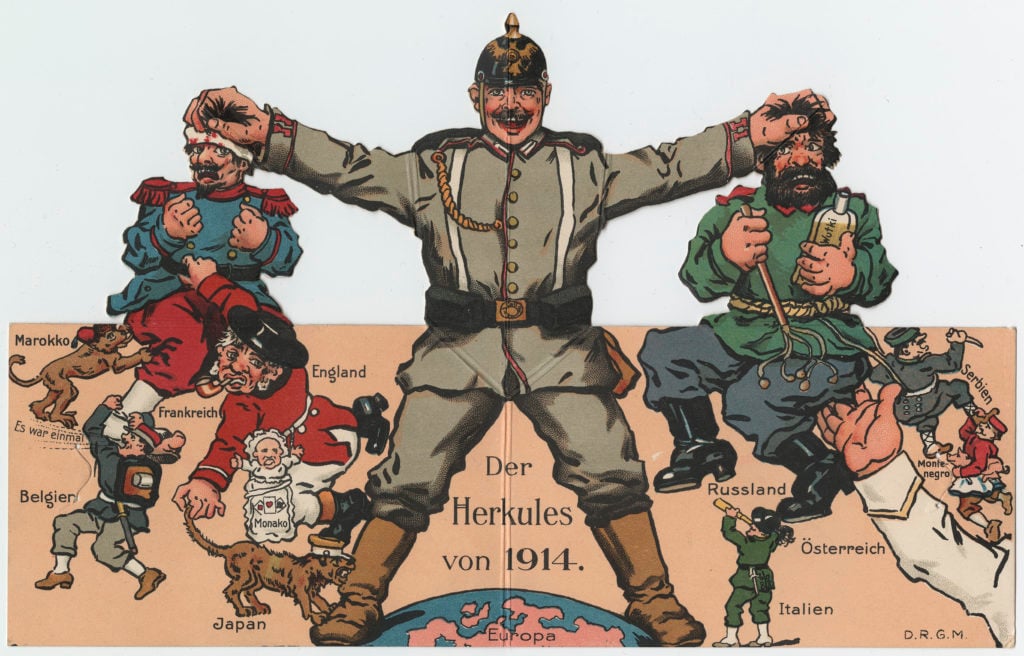

The Hercules of 1914 (pop up card; oversized). Color lithograph on card stock. Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive. Promised gift of Leonard A. Lauder. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The explosion of interest was also aided by a standardized international mail system and new postcard layouts. In early postcards, the address and image were displayed on the same side. Later, the address moved to the back of the card, which left the front side open for a larger image. In the process, postcards became collectibles, and a worldwide craze ensued.

“There were postcard clubs. There were postcard exchanges. There were postcard magazines. These things still exist today,” said Lynda Klich, an assistant art history professor at Hunter College and the curator of Lauder’s postcard collection.

Large and small producers, including artists, embraced the medium, which also afforded women new and more public voices. “It was a way for them to find jobs as working artists that were not in the mainstream art world,” Klich said.

Around World War I, the telephone proliferated and the postcard collecting craze died down, but propaganda and advertising became more prominent on postcards in the ’20s and ’30s. “They kind of kept the postcard going,” Klich said.

Japanese Soldier Devours the Russian Enemy. Color lithograph on card stock. Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive. Promised gift of Leonard A. Lauder. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Although contemporary society has many more avenues to present propaganda, Lauder believes that some things haven’t changed since the golden age of postcards. While exercising a few months ago on his elliptical machine, the collector saw a segment on television about people who claimed that Florida students angry at Senator Marco Rubio were in fact paid actors.

“We are so overwhelmed today with fact and not-fact and fake news,” Lauder said. “When you see this stuff in the propaganda book, you see that propaganda was really a fact of life for the world for at least 100 years leading up to today.”

For Lauder, who enjoyed the hunt inherent in collecting postcards, there is no clean divide between them and high art, like the 81 Cubist canvases he pledged to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2013. (The MFA Boston, meanwhile, mounted two previous exhibitions of his postcards in 2004 and 2012.)

“Cubism: The Leonard A. Lauder Collection ” at the The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 2014. (Photo: TIMOTHY A. CLARY/AFP/Getty Images)

“If you have a mind that’s far-reaching and broad, there is no way that you start to think of things in a linear way. I think with a wide-angle lens. I never know what comes into the lens,” he said.

As a child, Lauder went to New York’s Museum of Modern Art once or twice weekly to see movies. Waiting for the theater to open, he would wander the galleries and marvel at MoMA’s collection. “There was no separation between the love of the little postcards and the love of a big Picasso,” he recalled. “The fact that I paid a penny for the little postcard and could barely even afford the frame of the Picasso—that made no difference.”

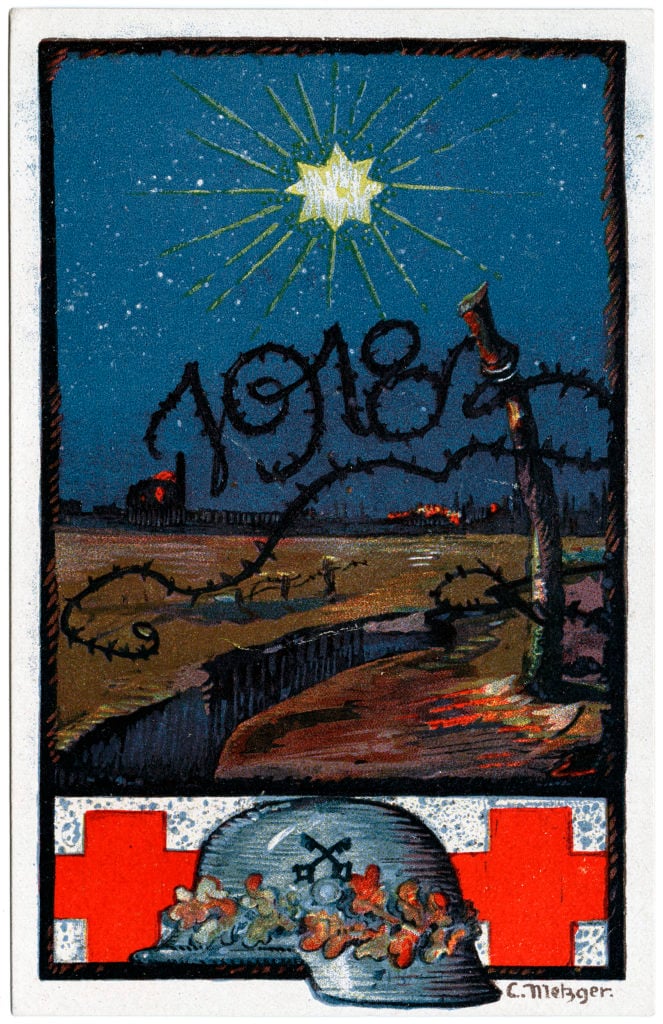

1918. Color lithograph on card stock. Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive. Promised gift of Leonard A. Lauder. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The images have stuck with him. Indeed, Lauder knew the contents of his shoe boxes so well that he was often able to direct the MFA’s curators to the exact boxes that stashed particular cards. He can also swiftly recall where he purchased most of the cards, and what drew him to them. “But,” he said with a laugh, “don’t ask me what I had for breakfast this morning. I’m not going to tell you.”

“The Art of Influence: Propaganda Postcards from the Era of World Wars” is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, from July 28 to January 21, 2019.