“You should focus on Jane, because she’s the leader of our art collecting,” says Marc Nathanson, the founder of Falcon Cable and current chairman of venture capital firm Mapleton Investments. This guidance rings true, even if it smacks of humble marital deference. Indeed, his wife of nearly 50 years, Jane Nathanson, is a more vital piece of the Angeleno art ecosystem than he is.

We are in a sitting room surrounded by Warhols, a Jasper Johns, and other dauntingly famous artworks. Marc reclines in a chair with both his arms on the rests, while Jane, across the table, munches on a carrot stick, perched forward with the attentive nature one might expect from someone who has practiced family psychology for decades.

Jane and Marc Nathanson attend the 2014 LACMA Art + Film Gala. Photo by Rich Polk/Getty Images for LACMA.

When they aren’t doing their day jobs, the couple are behind-the-scenes but extremely influential dignitaries in the LA art world. Their taste informs the art you see when you visit museums like the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), where, three years ago, they promised to donate $50 million worth of key works from their collection. For more than 40 years, the couple has invested a significant chunk of their net worth—a fortune even more significant since the sale of Falcon Cable for $3.7 billion in 1998—into art, which they eventually plan to distribute among the city’s museums.

Moving to Los Angeles

When the Nathansons moved to LA in 1976 from New York, they had been staples of the downtown Pop art scene populated by the likes of Andy Warhol and Tom Wesselmann. They found that LA—while home to influential artists including James Turrell and Robert Irwin—didn’t have a particularly buzzing scene for collectors.

In New York, everyone seemed to have a piece of art on their walls. But in LA, people were mostly motivated to install tennis courts or pools in their backyards. “Or buy a Ferrari,” Marc chimes in.

There wasn’t even a contemporary art museum—LACMA wouldn’t start collecting contemporary until the 1980s, and the Hammer wasn’t established until 1990. So when a friend introduced Jane to her aunt, the famed collector Marcia Weisman, Jane saw an opportunity to turn the city’s art scene on its head.

“I met her, and [philanthropist and collector] Eli Broad, and a bunch of people that were interested in contemporary art, and we decided there needed to be a contemporary art museum,” she says. The result was the founding of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, in 1979.

Jane chaired the board for the first few years of the museum’s existence—one that has famously struggled in recent years, with a revolving door of directors imported from New York.

“Hopefully, we’ll get our act together down there,” she says. “I feel like it’s one of my children. I very much want it to succeed, and I don’t think there’s such a thing as too many successful museums in a city, growing up in New York. They each have a place.”

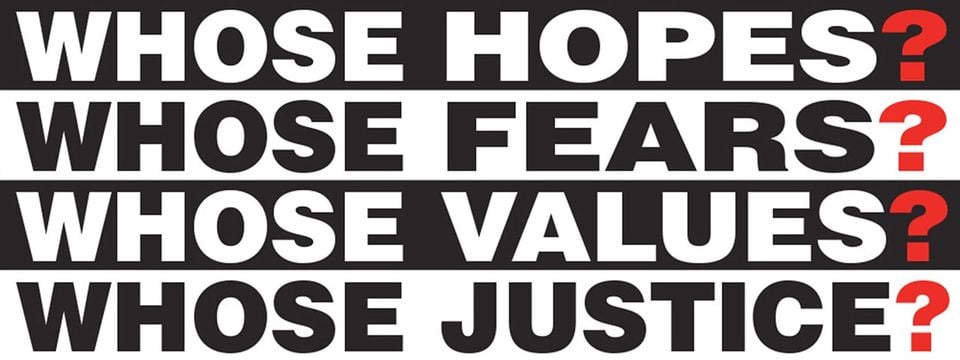

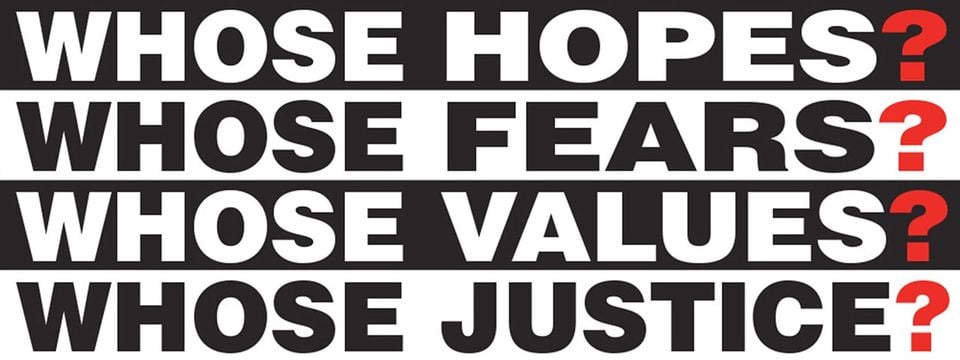

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Whose?) (2017). Courtesy of Jane and Marc Nathanson.

Looking to LACMA

Jane’s focus has since shifted across town to LACMA, where she is now a board member. The museum is racing against the clock to raise money for its $650 million expansion and is also looking to open a $30 million satellite in South Los Angeles, signaling heady times for LA’s art world as a whole.

“LACMA has one of the great art museum directors in the country if not the world,” Jane says with an almost gossipy whisper. “I think Michael Govan is genius.”

Being involved in museums has allowed Jane to keep up with the latest developments in the art world; the access to curators and Govan drives a lot of what the Nathansons end up seeing. And sometimes they return the favor—if they visit the studio of an artist they really like while traveling, they’ll report back to LACMA.

“We spend a lot of time looking at galleries [and] artist studios,” Jane says. “The great advantage sitting on a museum board is that you get to see things that are brought up for acquisition, or different studio visits that I think normally you might not have exposure to.”

They look for no less than the best examples by some of the most sought-after artists in the world. When they travel, it’s often to art fairs in Basel, Switzerland, or Miami Beach. They also make time to visit galleries wherever they are, including on a recent trip to Croatia.

Jane Nathanson and Michael Govan at LACMA’s 50th Anniversary Gala. Photo: MIchael Kovac/Getty Images for LACMA.

Keeping It Interesting

The duo first met while attending college at the University of Denver, where Jane was an art history major. She’s been giving Marc a lesson in contemporary art ever since. “Art has made our life and our marriage much more interesting, because it’s been something we’ve gravitated around, and have met a lot of wonderful people: artists, collectors, and even dealers,” Marc says.

Because as much as the Nathansons have collected art over the years, they’ve also been collecting stories. Like the one about the Jasper Johns Target painting hanging over my shoulder that Jane saw at a house party in the Hamptons. She went up to the host and asked if it was for sale—thankfully, the host was Larry Gagosian, and, it turns out, it was available for purchase.

“Everything’s for sale at Larry Gagosian’s,” Jane quips.

And then there was the time they were at a dinner party sitting next to collector Dennis Scholl when he asked Jane, “If you could have one piece that you don’t have, what would it be?”

Jane thought for a second, and said, “I’m looking for a Warhol Double Elvis. And I’ve looked for years for one.”

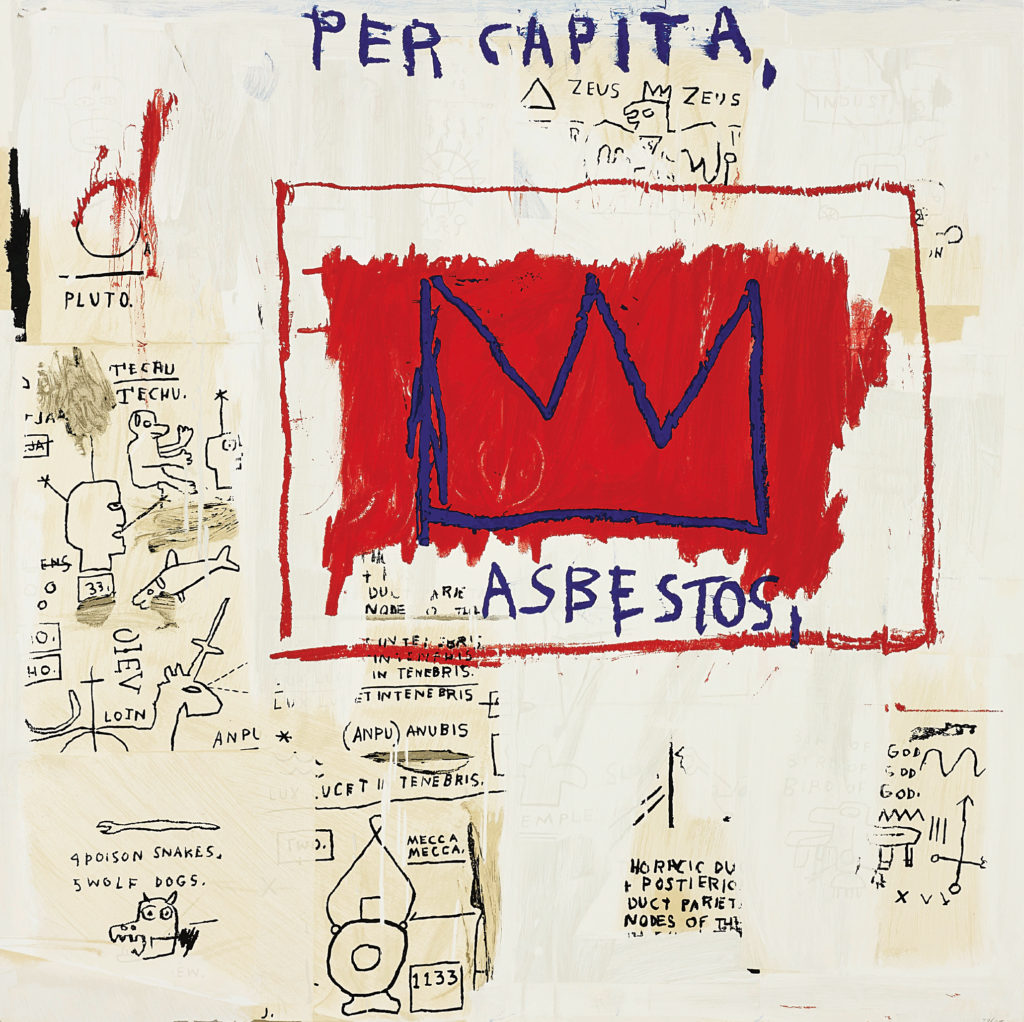

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Per Capita, from Portfolio I (1983/2001). Courtesy of Marc and Jane Nathanson.

Scholl looked at her and said, “Well, you’re not going to believe this, but I have a friend whose son was a friend of Andy Warhol, and when he did the Double Elvises, he gave him one, and he gave it to his father, and I think he’ll sell it.”

They started negotiations within a week.

“That’s how we got the Double Elvises,” says Jane with a smirk. “That was serendipity.”

This is characteristic of their collecting style. They don’t just get an Urs Fischer to tick him off a list—they get the Urs Fischer they want.

“We search for a long time,” says Marc. “We can’t collect artists en masse, because we like as much as we can to see it in our house. So you want a really good piece. Like we wanted a Lichtenstein [from the early] early ‘60s,” he adds, referring to Woman With Peanuts (1962), a painting of a waitress holding a plateful of peanuts that are shaded with the Ben-Day dots that would later become a hallmark of the artist’s work.

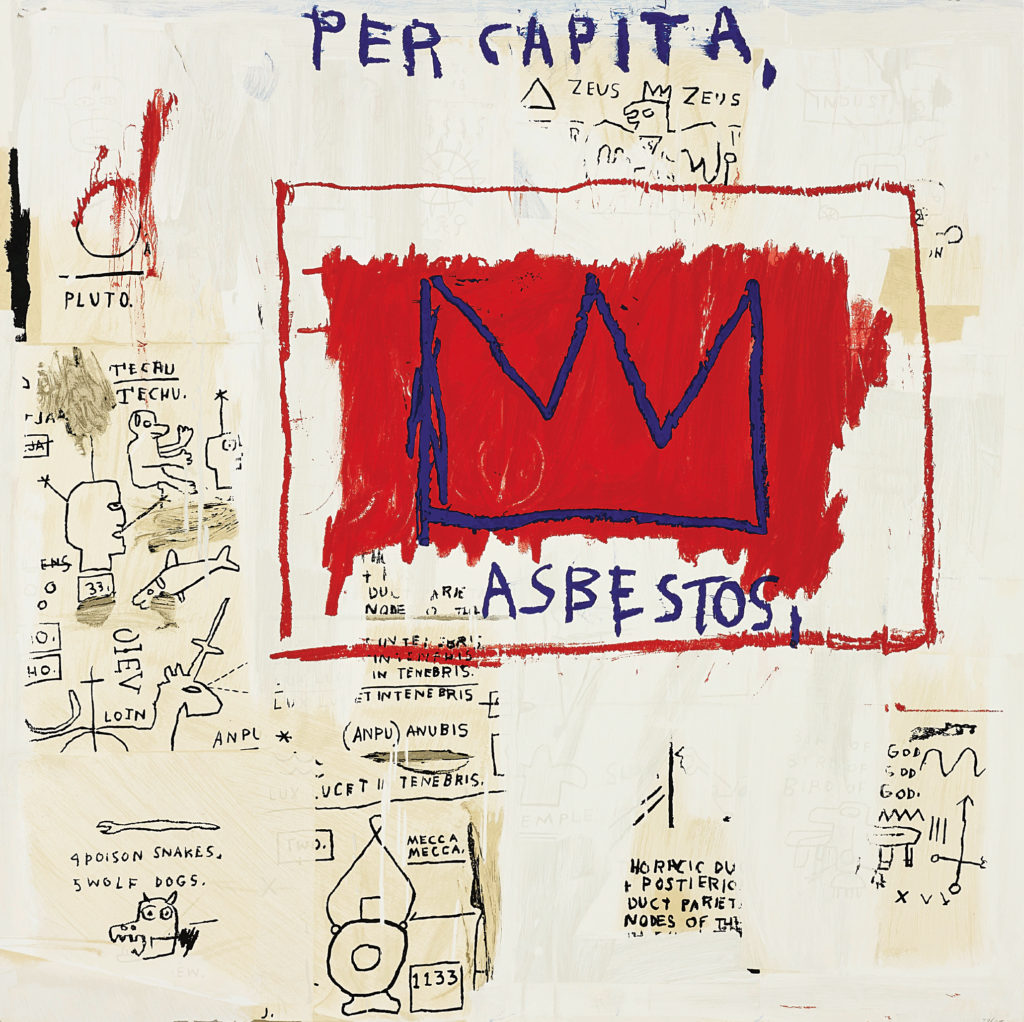

Jeff Koons, Sacred Heart (Blue/Magenta) (1994–2007). Courtesy of Marc and Jane Nathanson.

Giving It All Away

Another Lichtenstein work, Interior with Three Hanging Lamps (1991), is one of eight works that the Nathansons promised to LACMA on the occasion of the institution’s 50th anniversary. The ultimate goal is to divide their impressive collection among Los Angeles’s museums—with each of their three children getting only one piece each.

“LACMA was a natural gift for us,” says Jane. “I was chairing the 50th Anniversary party, and my idea was, ‘What do you give a museum for its birthday? Art.’ Especially, LACMA needs more contemporary art. So we did art valued at $50 [million] for its 50th birthday, and then encouraged other people, and they did once we gave.”

Exactly where the rest of the 400 works in their collection will land is still up in the air. But the Nathansons are committed to donating the work rather than setting up their own private museum, like fellow LA mega-collectors Eli Broad or Maurice Marciano.

A Franz Kline from 1961 hangs over the fireplace, while a massive steel Jeff Koons Sacred Heart presides over the backyard. There are quite a few Ed Ruschas and several Basquiats, including one Jane bought for Marc on his 35th birthday (he’s 73 now) for $5,000 (“It was a nice birthday surprise,” Marc says. “But it was too much money, I told her.”).

Elsewhere, I spot a Cathy Opie (“We looove Cathy,” says Jane); a Matisse from Jane’s family’s collection that was previously owned by British writer M. Somerset Maugham; a de Kooning; a Kara Walker; a John Chamberlain; a Parker Ito; several Calders; a trippy Anish Kapoor concave mirror that is dizzying to even approach; a Cindy Sherman; a Doug Aitken; and a Barbara Kruger—all of which will eventually end up in one of the city’s museums.

“Now, we’re sort of in the wait-and-see period—which museums will get what?” says Jane. “We haven’t made a definite determination. Our feeling is: Los Angeles needs more art than New York. New York already has some pretty good donors, and most of the museums have great collections already. So we would like to see it where it will be seen the most, but we’re not ready to give it up quite yet.”