People

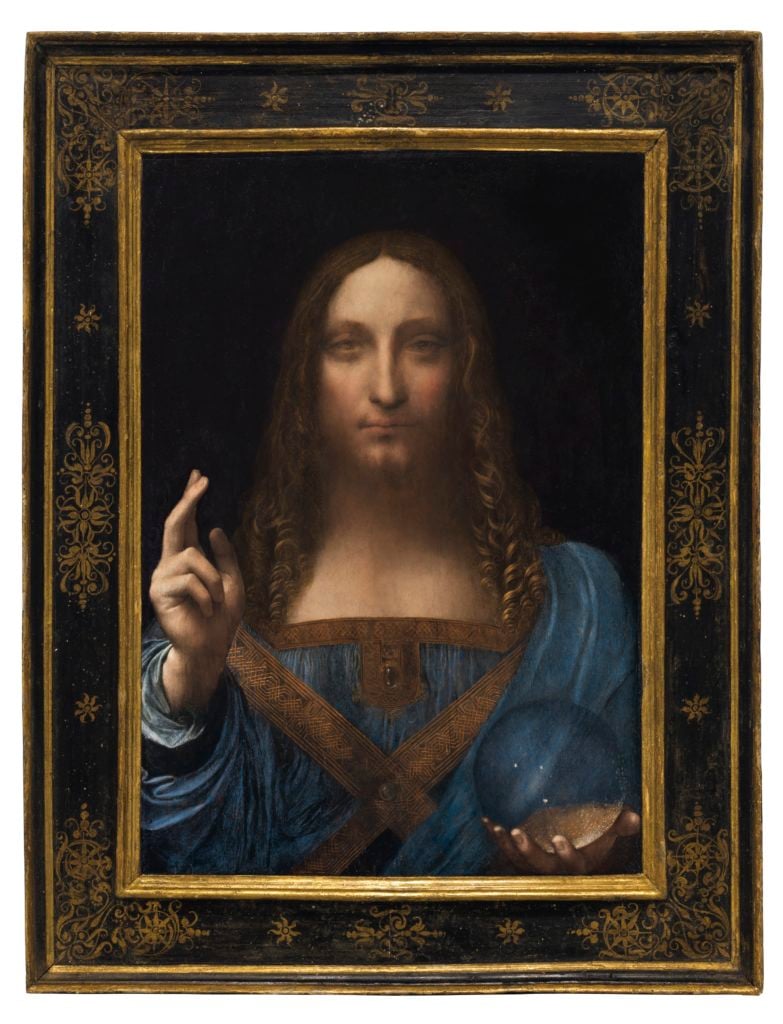

Why Are Experts Perplexed by Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Salvator Mundi’? (Hint: It’s That Weird Orb)

With a major new biography and movie to follow, is this the start of da Vinci delirium?

With a major new biography and movie to follow, is this the start of da Vinci delirium?

Eileen Kinsella

Is it a rift between art and science or just artistic genius at work?

In what looks to be the start of Leonardo da Vinci delirium, art experts and scholars (including us) are geeking out over a mystery highlighted by Walter Isaacson in his spectacular new biography, Leonardo da Vinci (Simon & Schuster).

The riddle centers on the orb in the left hand of Jesus in the Leonardo da Vinci painting Salvator Mundi (Savior of the World), which Christie’s is planning to offer for $100 million at a New York auction next month.

“Leonardo failed to paint the distortion that would occur when looking through a solid clear orb at objects that are not touching the orb,” Isaacson writes in the book. Solid glass or crystal—be it an orb or a lens shape—yields magnified inverted or reverse images. However, as Isaacson points out, Leonardo painted the orb “as if it were a hollow glass bubble that does not refract or distort the light passing through it.”

Isaacson doubts it was an issue of ignorance, especially given that Leonardo was conducting optic studies that explored how the eyes focus around the same time that he painted Salvator Mundi. The artist was well aware that he could create the illusion of three-dimensional depth by making objects in the foreground sharper, as demonstrated with the raised right hand that practically pops from the picture “as if it’s in motion and giving us a blessing.”

Isaacson ponders whether the “puzzling anomaly” in the painting is “an unusual lapse or unwillingness by Leonardo to link art and science.” After all, the artist spent countless hours researching how light works. “Scores of notebook pages are filled with diagrams of light bouncing around at different angles,” he writes.

Optical inaccuracy aside, the orb is rendered with “beautiful scientific precision,” including three bubbles that signify tiny gaps in crystal known as “inclusions.” Isaacson says that around this time, Leonardo had evaluated rock crystals as a favor to Isabella d’Este, the Marchesa of Mantua, so he knew how to capture the detail of the twinkling inclusions.

If Leonardo had accurately painted the distortions as they would occur, he says, the palm touching the orb would have remained the way he painted it, but “hovering inside the orb would be a reduced and inverted mirror image of Christ’s robes and arms.”

artnet News did some digging and found that numerous other Salvator Mundi paintings, by other artists from around Leonardo’s time, also don’t invert the image. Some orbs are clear like Leonardo’s, while others have mountainscapes inside them.

The Leonardo painting, once owned by English king Charles I, already has an illustrious history, including having vanished for hundreds of years before surfacing on the art market circa 1900. It was sold at auction for £45 ($60) in 1958. Far later, around 2011, it was authenticated by a group of respected scholars as the real deal after lingering doubts.

In 2011, prominent Leonardo da Vinci scholar Martin Kemp told Art + Auction that one of the things that convinced him of the attribution was the orb itself. Noting the artist’s expertise on rock crystal and its properties, he says Leonardo painted a slight refraction—two heels of the hand—underneath the globe, a visual phenomenon that is consistent with Kemp’s own experiment with a similar large crystal ball at the Ashmolean Museum.

Asked to weigh in on the conundrum, Alan Wintermute, a senior specialist in Old Master paintings at Christie’s, told artnet News: “Whatever Leonardo’s reason, we know that visual riddles and conundrums are characteristic of his great masterpieces. It is part of what makes this painting both a beautiful and intellectually engaging example of the great master’s work.”

Isaacson seems to agree, writing, “I suspect that he knew full well… but he chose not to paint it that way… because he was subtly trying to impart a miraculous quality to Christ and his orb.”

Miraculous or otherwise, the mystery around the orb appears to be generating even more buzz for a title that’s been on something of a roll. In August, Paramount Pictures acquired the rights to Isaacson’s book after a seven-figure bidding war. The forthcoming film adaptation will feature another famous Leonardo—DiCaprio—in the title role.

Additional reporting by Hannah Pikaart.