Photo: courtesy Samuelis Baumgarte Galerie

Amah-Rose Abrams

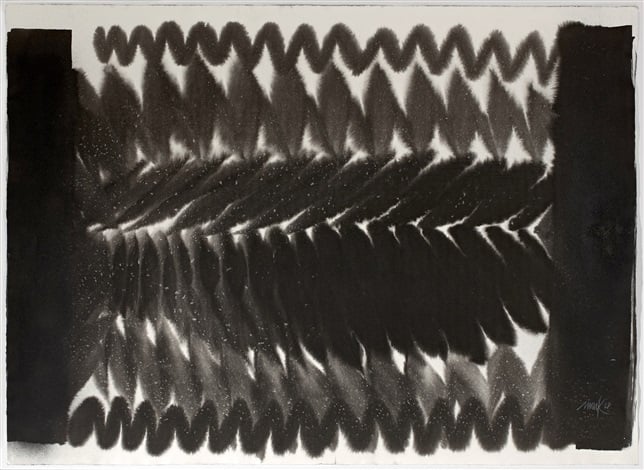

Heinz Mack Wing-Wing (2015)

Photo: courtesy Samuelis Baumgarte Galerie

Painter and sculptor Heinz Mack has enjoyed a prodigiously long career. As a co-founder of the hugely influential ZERO movement, he is known for a breadth of inventive work which includes light sculptures, large-scale environmental installations, op art, kinetic art, and more.

Born in Lollar, West Germany in 1931, Mack attended the Düsseldorf Academy from 1950–1953. Three years after graduating, he left the city to study philosophy in Cologne, a qualification he needed to gain work as a secondary school teacher. Despite the creative buzz that was booming in the Rhineland at the time, this was still a bleak period in Germany’s history as, following the end of the Second World War in 1945, there was massive damage to infrastructure and high levels of poverty.

Heinz Mack O.T., (1968)

Photo: courtesy MDZ Art Gallery

“Even in the library of the well-reputed Academy in Düsseldorf, there were three or four old books left: there was no information at all,” Mack explained in an interview with Ocula in 2014. “To give you a simple example, because I worked quite hard as a student, I received a scholarship from the state—just enough money to go from Düsseldorf to Paris by train. I was so happy and so excited to see, at the Grand Pavilion, paintings by Picasso, Miró, and Matisse for the first time. When I came back a week later to my Academy in Düsseldorf, I told my friends about a very strange artist I’d never seen before, Miró, and nobody, not a teacher or a student, had ever heard his name!”

Mack and fellow Düsseldorf graduate Otto Piene founded the ZERO Movement in 1957. ZERO, which was named to express an affinity with the Minimalist movement, was concerned with freedom, breaking from tradition, and the use of simple forms, light, and color. Together, they also published ZERO Magazine which went on to run for a decade, from 1957–1967.

Heinz Mack O. T. (1960)

Photo: courtesy Beck & Eggeling

Mack and Piene, joined in 1961 by Günther Uecker, hosted evening exhibitions at their studios that gave themselves a platform in which to show their work when no other opportunities existed. This allowed them to find and engage with an audience while displaying their latest—often still in-progress or unrealized—work.

By the late 1950s Mack, started working directly in desert and arctic landscapes in an effort to explore light in natural environments. In 1959 he completed the Sahara Project, where he installed what he refers to as “gardens” in the vast sand dunes of the Sahara. These installations comprised of mirrored glass, sails, prismatic pyramids, and huge “light-flowers.” Mack’s sculptural works used both reflective and textural surfaces to maximize the striking impact of the desert and arctic sun.

In 1964, Mack, Piene, and Uecker contributed several works, including kinetic sculptures, to documenta III under the title of “ZERO Lichtraum (Hommage á Lucio Fontana).” The trio quickly began to attract attention from overseas.

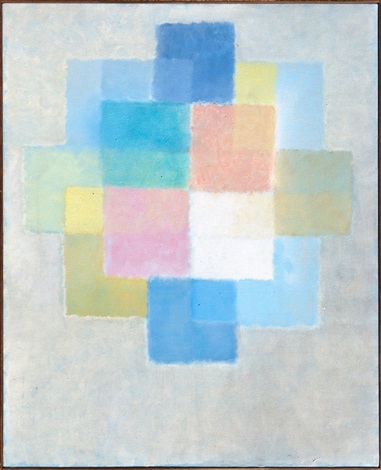

Heinz Mack I Like the Colour of Your Mind (2008)

Photo: courtesy ARNDT

Shortly after, Mack moved to New York and held his first solo exhibition at the Howard Wise Gallery in 1966. Many of the artists affiliated with ZERO spent time in New York where, to this day, the artistic community still holds the movement in great affection. In 2014–2015 the Guggenheim Museum mounted “ZERO: Countdown to Tomorrow, 1950s–60s,” a major survey of the movement.

Over time, ZERO developed into a global network of like-minded artists that included Yayoi Kusama, Yves Klein, Lucio Fontana, Piero Manzoni, and Jesús Rafael Soto, and was linked to many other overlapping artistic movements, such as Arte Povera, Nouveau Realismé, and Minimalism.

“The main thing is that all the artists that were or have been involved in the spirit of ZERO in general are working with structures,” Mack explained to Ocula. “These artists are making concrete not realistic work: it’s just structures—and behind these structures is the idea of light, space, and movement.”

Heinz Mack Ohne Titel (2014)

Photo: courtesy Samuelis Baumgarte Galerie

Throughout his career Mack received many commissions for public sculpture, including at the Jürgen-Ponto-Platz in Frankfurt, the Platz der Deutschen Einheit in Düsseldorf, and, probably the most famous, Sky Over Nine Columns (2014), consisting of nine large gold columns installed for the 2014 Architectural Biennale in Venice.

Lately, however, Mack has resumed painting in color after decades of relying on a palette of mainly black and white, or a single color at a time. Viewing “color as light and light as color,” he creates vibrant works governed by the juxtaposition of saturated hues, focusing on blurring their boundaries to create a dazzling, jewel-like effect.

Ardently Modern, Heinz Mack is still creating fresh and inspiring works. His efforts have not gone ignored, and recent groups shows focusing on the ZERO movement at the Guggenheim and Neuberger Museum of Art attest to his lasting impact on the history of 20th-century art. Hopefully it won’t be too long before we also see a large-scale solo museum survey of his work—he’s certainly earned it.