Lina Iris Viktor is reveling in the most ancient of materials—marble, gold, ceramic, bronze, wood. The British-Liberian artist has, of late, been contemplating the ways in which time itself can be embedded into an artwork, questions stirred by the 36-year-old artist’s recent move to Sorrento, Italy, a terrain uniquely rich in antiquity.

“These are materials we see frequently in Renaissance works in reference to the divine. With marble or gold, it took thousands of years for these materials to be created,” she said in a phone call. “As an artist, you’re able to take these millennia-old materials and form them into something else that will also last forever.”

Lina Iris Viktor. ©2023 Courtesy of LVXIX Atelier.

Viktor, who previously divided her time between Italy, downtown New York, and London, made the move to the Amalfi Coast with her three dogs earlier this year. She’s spent the past several months building out a studio in her new home, one that shares some similarities to her former New York studio, which was notorious for its distinctively hued “Blue Room,” a small, chapel-like space saturated in blue situated within her otherwise bright white studio.

“In my old studio I had a Blue Room within a white studio space,” she noted. “Here I have a white studio space, a Red Room, and a Black Room. These are spaces for showing work but also a place to decompress. I always like to have a separate space within the overall space to have a moment.”

The relocation has also encouraged the artist to consider a different pace for her practice. “In Italy, as you can imagine, life moves more slowly, and even more so in the south,” said the artist. “I would recommend people get out of their comfort zones. Living in Sorrento is in a time warp. It’s a different time, maybe like the 1960s, and there’s not a strong sense of the contemporary art world or market. People aren’t quite sure what I’m doing here.”

Lina Iris Viktor, Eleventh (2018). © 2018. Photo courtesy of the artist.

This out-of-era experience seems fitting for Viktor, who is known for weaving together histories, visual traditions, and

epochs in her mixed-media creations. “I pull from all kinds of times and cultures. People want to compartmentalize, but thought and knowledge are universal,” she noted of her myriad references. Viktor credits this encompassing artistic appetite to her childhood education in London at Marymount, a Catholic boarding school with a strong international presence. “I grew up with girls from Mexico, Thailand, Saudi Arabia, Japan, Korea, with people of all kinds of religions, nationalities, races,” she said. “And this was at an age before jadedness sets in, when you’re very pure and innocent, and sincere. I had an appreciation for all kinds of cultures, peoples, and religions from a very early age. Even now, I don’t see the borders of the world.”

Viktor went on to study film and theater at Sarah Lawrence College in New York. Cinema still shapes her approach to art making. “My film history teacher’s name was Gilberto Perez. Through him, my world opened,” she said. “I felt like my third eye opened when I started taking his classes. The way I see is still very filmic.”

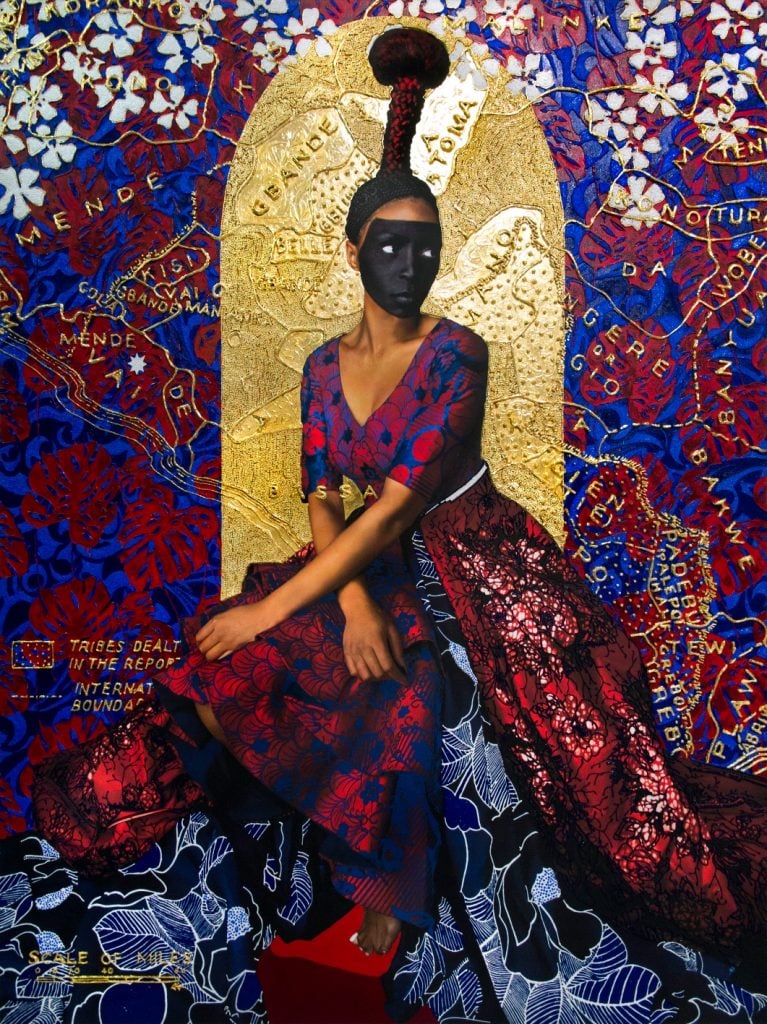

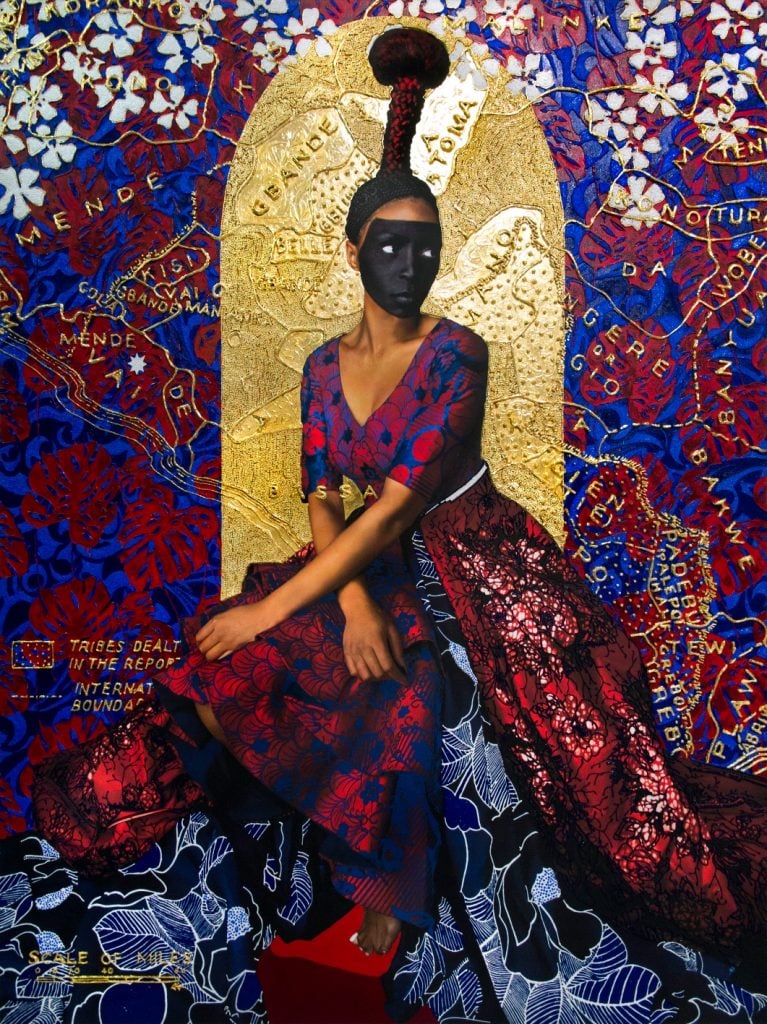

After graduating she briefly pursued a career in film before transitioning into a studio art practice. Self-taught as a visual artist, Viktor’s star first rose in the mid-2010s with a series of majestic self-portraits that melded black-and-white photography, gold leaf, and a sculptural approach to applying paint to canvas (a breakout show at 151 Gallery in 2014 put her on many radars).

Lina Iris Viktor. ©2023 Courtesy of LVXIX Atelier.

Defined by a palette of luminous blacks, gold, crimson reds, and Majorelle blues, these regal portraits dazzled with intricate, sculptural motifs in paint that Viktor painstakingly piped onto the canvases. Such works call to mind French miniaturist Jean Fouquet’s famed Madonna, Kabuki theater, Secession-era Gustav Klimt, ancient Egyptian goddesses, and, of course Yves Klein. Over the decade that followed, she created celebrated figurative series including “Constellations,” “Materia Prima,” and “Dark Continents”—the last of which focused on mythological representations of Liberia’s creation (these works presented in “A Haven. A Hell. A Dream Deferred,” at the New Orleans Museum of Art in 2018).

Installation view of Lina Iris Viktor’s works for “In the Black Fantastic” at Hayward Gallery, London, 2022. Lina Iris Viktor. ©2023 Courtesy of LVXIX Atelier.

Today, Viktor is preparing for two upcoming London solo exhibitions in 2024, first at Pilar Corrias, her representing gallery in the spring, and the other at the Sir John Soane Museum later in the year. These exhibitions will be standalone follow-ups to several powerful recent group shows that featured her work, including 2022’s “In the Black Fantastic,” curated by Ekow Eshun at Hayward Gallery, which brought together 11 artists of the African Diaspora who draw on science fiction, myth, and Afrofuturism in their work. “Rite of Passage” at LGDR’s London location last year, meanwhile, hinted at the directions Viktor is now pursuing, presenting her recent forays into sculpture as well as monochromatic gold abstractions. These important new works were juxtaposed with works by César, Louise Bourgeois, Louise Nevelson, and Klein, all artists who have influenced her oeuvre.

In these recent works, all traces of self-portraiture have disappeared. Instead, Viktor offers up complex map-like golden surfaces that glitter against the eye. “I’m a contradictory person. I’ll say one thing and mean it, but I also don’t want to pigeonhole myself,” said Viktor when asked about her recent move toward abstraction, “Yes, though, abstraction is where my interest is, even with the new sculptural works. I’m willing to take that risk now and go there wholeheartedly.”

The reasons for this transition are multifaceted. She’s grown tired of the rage for figurative art. “Figurative works are a very easy way to get people’s attention—it’s the normal human response to figure in that people see themselves in it,” she said. “Now I see so much figurative work out there, and so much reading of identity, particularly when it comes to Black artists. When I started this in 2013 and 2014, it was still regarded as not of the time. It wasn’t contemporarily interesting to people. These are continual cycles. But right now, figuration is not really pushing any conversational boundaries.”

A newfound interest in sculpture is also leading the way for these shifts. “The number of materials I use in my works is expanding. I’ve always been interested in my work extruding. There is a relief-like aspect to my canvas works. But on a two-dimensional surface, you can only do so much,” she said, “Recently I’ve been looking at pottery and vessels; I’ve been wanting to draw out in space and think in a more dimensional way. I am starting to see how my work can exist within that third plane.”

Many of their recent forays into sculpture have been through marble. “It wasn’t so much that I wanted to use marble because I’m in Italy. I’m just using marble and I happen to be in Italy,” she explained. “It’s opening up so many new vistas for me.”

Installation view of “Rite of Passage: Lina Iris Viktor with César, Louise Bourgeois, Louise Nevelson, and Yves Klein” at LGDR, London, 2022. Courtesy of LGDR.

These natural, earthly materials are drawing out a spiritual thread that runs through her works. “I have often been compared to Yves Klein, who was a very influential artist to me. I see that particularly in questions of the use of gold and earthly matter,” she said. “Klein wanted to take people out of seeing these materials as monetary tools or away of representing wealth and bring back the spiritual into the materiality of it, as a symbol of the eternal.”

Her ambitions for three-dimensional creation expand from sculpture into the world of architecture, too, an interest that will be on display in her upcoming exhibition at the Sir John Soane Museum.

“The museum space was originally the architect Sir John Soane’s home. It’s a space dedicated to his architectural vision as well as his voracious collecting habits,” she noted. “Especially with the abstract works, my references to architecture are very strong.”

Lina Iris Viktor. ©2023 Courtesy of LVXIX Atelier.

Where will these varied pursuits ultimately lead? Viktor thinks her passions will manifest in an edifice for her works to inhabit.

“Building an actual space would be the dream. The canvases can create the desired effect in any space, but for me, it’s the difference between seeing Rothko’s work in the Rothko Chapel versus hanging in the Seagram Building,” she said with a smile. “I’d love to marry my interests with architecture and space-building, experience-building, painting, sculpture and film together so that they each have their own little niches or spaces, but held within the schema of unified environment.” She namechecks one inspiration—James Turrell’s Roden Crater, the American Light and Space artist’s colossal land art project in the desert of northern Arizona. “A place you make a pilgrimage to interests me,” she said. “Not even a pilgrimage in terms of a long distance to travel, but as a place to experience and spend time with art.”

For now, in the remote beauty of Sorrento, the artist is allowing herself the space to dream up her grandest ambitions without urban distractions. “Lately, I’m less desiring of accolades or inclusions, the trappings that can come with this career. I just want to make things that I think matter at not think about whether it is with of or against the grain of the art world,” she said. “I’ve always respected people like Sade or Chris Ofili who just drop in as though coming out of the ether, do their thing and then disappear and you don’t hear from them again until the next time. There’s something very mystical and beautiful about disappearing like that.”