Up Next

Breakthrough Artist Bethany Collins Mines the Poetic Potential of Paper

Collins is the subject of a debut solo show with Alexander Gray Associates, and is the recently announced winner of the Jacob Lawrence Prize.

Collins is the subject of a debut solo show with Alexander Gray Associates, and is the recently announced winner of the Jacob Lawrence Prize.

Annikka Olsen

“Paper is fragile, and it’s temporary. It heals itself but it holds abrasions to its surface,” said Bethany Collins on a video call in the days leading up to her exhibition “Undercurrents” with Alexander Gray Associates in New York. “It shows everything—the life of the paper. It’s as much a metaphor for the body as I can find in material form,” she explained.

The exhibition, on view through December 16, 2023, is her first with the gallery, which she joined late last year. “Undercurrents” traces Collins’ interrogation of language, text, and the limits of paper as a medium. The show traverses four key bodies of work, which engage with everything from Ancient Greek literature to the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020.

Bethany Collins, Old Ship II (2023). © 2023 Bethan Collins. Courtesy of Alexander Gray Associates, New York; Patron Gallery, Chicago.

A newer addition to her practice is a series of cast paper works, part of the “Old Ship” series. “They’re not language-based, so the work makes me nervous,” Collins said with a laugh. Created with handmade paper mixed with pink granite dust from the base of the since dismantled Confederate monument to Stonewall Jackson in Charlottesville, Virginia, the works are molded in the shape of architectural details from the Old Ship AME Zion Church, the oldest Black church in Montgomery, Alabama, Collins’s hometown. Made in collaboration with Dieu Donné in Brooklyn, these works are slated for exhibition with LAXART and MOCA LA in 2025. “I like this idea that the monument to a traitor that’s been exalted on the landscape for so long, that its destruction then could aid in the support of another kind of monument. It’s also of another space, another community, another story that’s much more worthy of remembrance.”

Bethany Collins, The Flag with Thirty-Four Stars (2023). © Bethany Collins. Courtesy of Alexander Gray Associates, New York; Patron Gallery, Chicago.

The exhibition continues with a selection of “song drawings,” works that engage with contrafactum, a term used in music to describe songs where the melody stays unchanged, but the lyrics are altered. One of the primary source materials Collins used, enlisting the assistance of a composer in creating the compositions, was the song “The Bonnie Blue Flag,” which was sung widely by Confederate soldiers during the Civil War, with Union soldiers adapting and creating their own renditions—the latter of which Collins used exclusively in the work.

“I worked with a composer to transpose the song into the circular scores to mimic Haydn’s Ten Commandments circular scores, the never-ending quality of them. And then they also become polytonal, they’re very chaotic and eerie,” explains Collins. “I’m working with only union versions, so there’s this attempt at resistance to the predominant narrative.”

The works also feature charcoal clouds evocative of tear gas used during the summer protests of 2020, inspired specifically by images taken in South Carolina—the first state to secede—shown in the state newspaper. “The drawings, I’m hoping, are a way to collapse and haunt time; 2020 didn’t come out of nowhere. It is very much traceable into our past.”

Bethany Collins, Years, 1865 (The Sun) (2023). © Bethany Collins. Courtesy of Alexander Gray Associates, New York; Patron Gallery, Chicago.

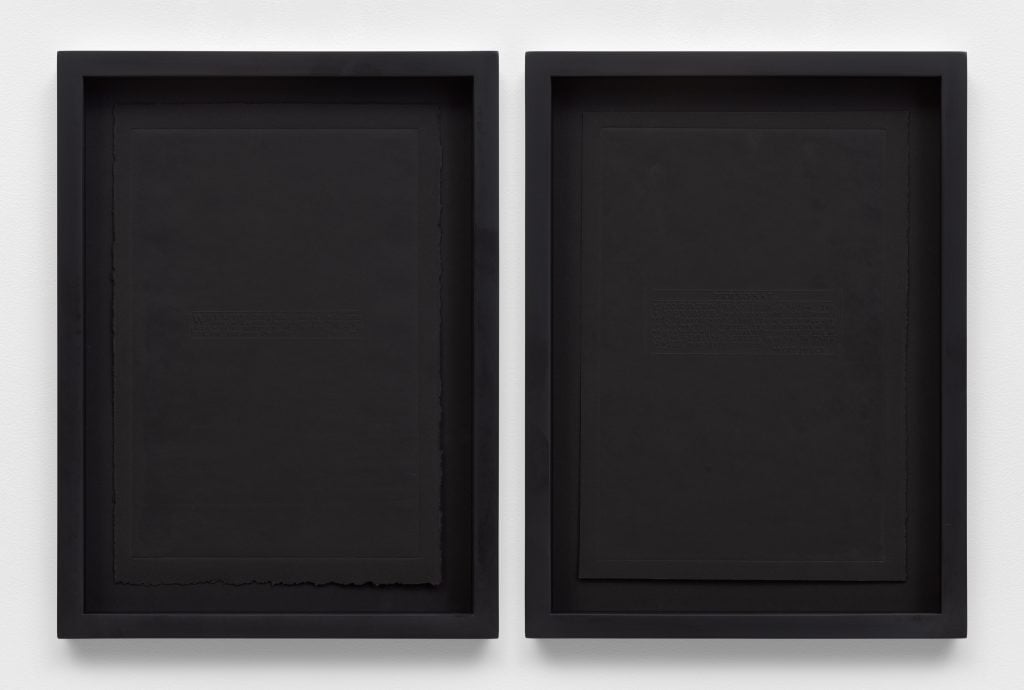

Also engaging with the American Civil War era, the series “Lost Friends” traces Collins’s research into a specific type of notice written by individuals looking to locate formerly enslaved friends or family members. These messages were printed in newspapers, displayed publicly, or read in churches beginning in the years just before the end of the Civil War and through to about the 1920s. The commonalities in the texts found by Collins—“Can you help me to find my people?” “I am all alone in the world” or “Will the ministers of the South please read this from your pulpits”—created a “kind of chorus of longing.” Isolating quotes from these notices and blind embossing them onto a monochromatic ground, the works center the psychological anguish of loss and uncertainty in the wake of war.

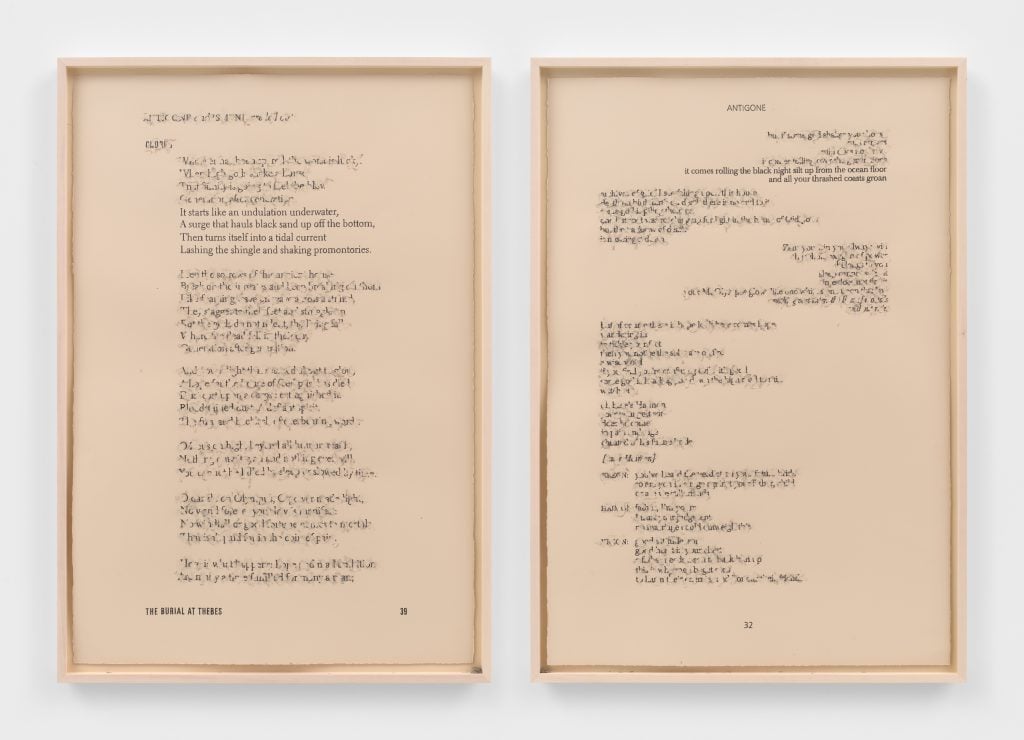

Bethany Collins, Antigone: 2004 / 2015 (2023). © Bethany Collins. Courtesy of Alexander Gray Associates, New York; Patron Gallery, Chicago.

Reaching farther into the depths of history is the “Antigone” series. “I’ve been working with the epics for a while now, since around the 2016 election,” said Collins. “All of those big texts we turn to in times of crisis for metaphors for how to deal with every present moment we go through, we look back to the past. They suck up all the oxygen in the room.”

Here, Collins uses her own saliva to erase and obscure part of the printed text, which is reproduced across multiple panels. “The spit is also important because it’s a way to insert my body into the work and to exert control. Language feels so unwieldy, and a lot of time the thing that should make sense, it doesn’t make sense. So, the insertion of my body and my erasure of it is a way to become master of this unwieldy system.”

The lines and passages that are left intact highlight moments of extreme drama, uncertainty, and resolve—notions that resonate across time and place from antiquity through today, and speak to the unifying “undercurrent” of the exhibition: it is the small, repeated acts, both individual and collective, that bind our humanity, and connect us with generations past as well as with the future.

“‘Antigone’ and the ‘Lost Friends’ are separated by centuries and are very different people and circumstances, but they are both responses to the aftermath of civil war. That kind of chorus of longing, they both become a kind of chorus that collapses time. And I think they’re also not just a kind of resistance and ritual, but also indicate a faith in reunification, that what you do still matters, even in that moment.”

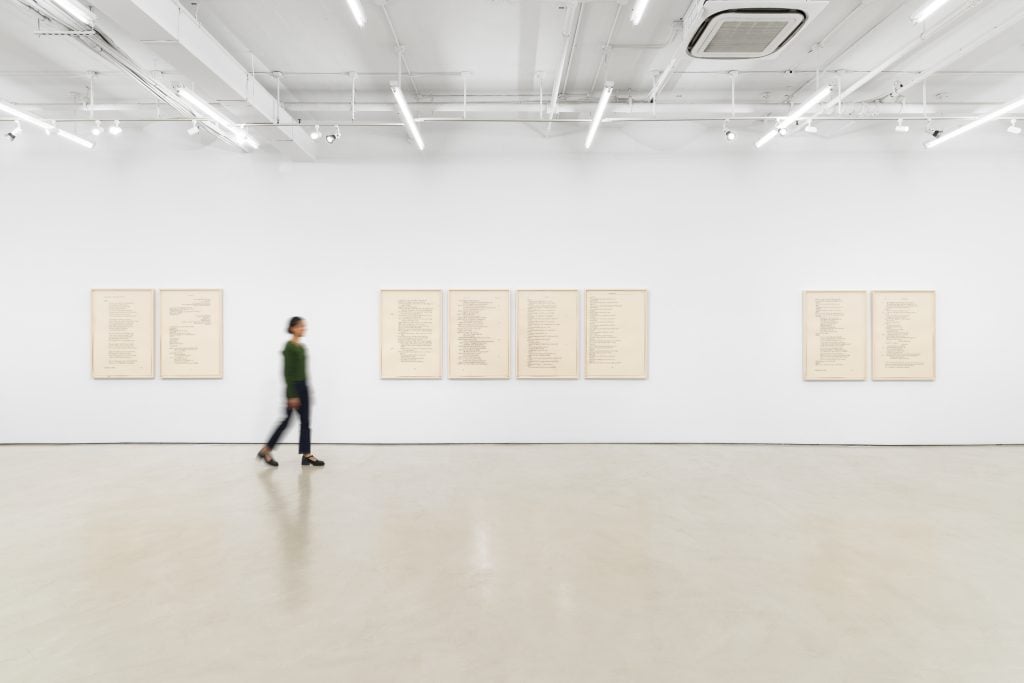

Installation view of “Bethany Collins: Undercurrents” (2023). Photo: Dan Bradica. Courtesy of Alexander Gray Associates, New York.

Though Collins’ widespread use of paper in her practice works as a metaphorical stand-in for the body and offers myriad conceptual lines of inquiry, it is perhaps its quotidian quality that grants her work an exceptional level of resonance. Engaging with historical through lines, both in terms of events and lived experiences, her meticulous and detailed interventions—their act and index—in and on paper materially embody the core theme of the show: “all of ‘Undercurrents’ is about small choices as acts of resistance. Mourning, and ritual as resistance. That’s the heart of the show.”

The exhibition is an exceptional moment to become acquainted with Collins’ poetic style and materially resonant body of work. Earlier this year, it was announced she was the recipient of the Seattle Art Museum’s (SAM) Gwendolyn Knight and Jacob Lawrence Prize for 2024. The prize, conferred biannually to an early career Black artist, grants the awardee $15,000 to advance their practice as well as a solo exhibition at SAM, which Collins will be the subject of next year—another in a string of significant career moments.

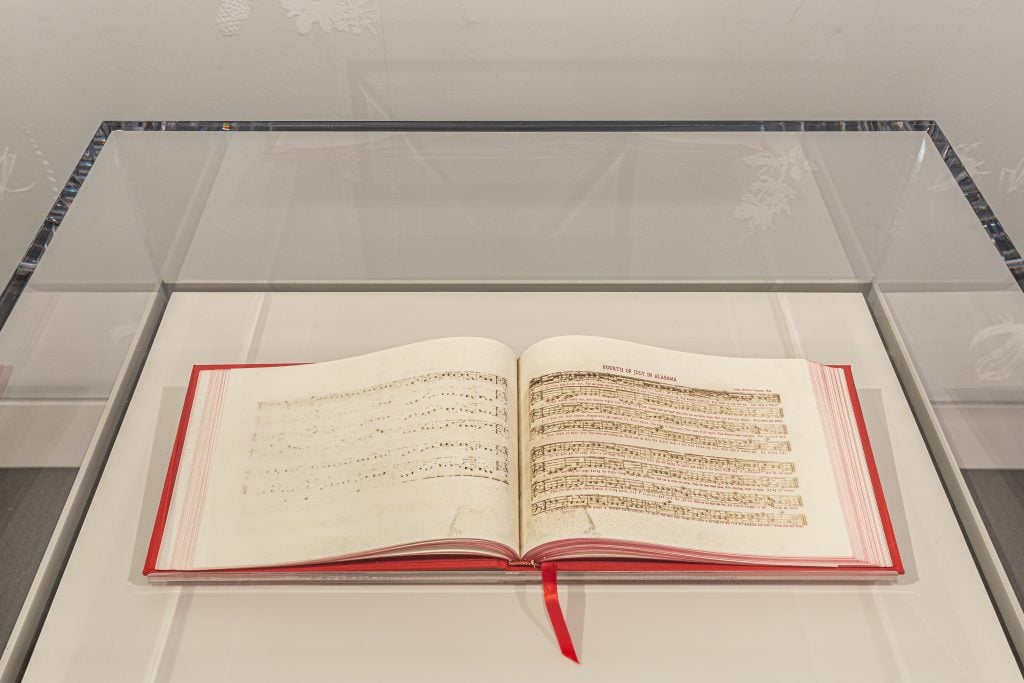

Installation view of “Bethany Collins, America: A Hymnal” (2023). Photo: Kathy Tarantola. Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA.

For Collins, 2021 was also a banner year, with three independent institutional solo shows staged across the United States. “My Destiny Is In Your Hands” at the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, Alabama; “Evensong” at Frist Art Museum, Nashville, Tennessee; and the debut of “America: A Hymnal” at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas.

The Crystal Bridges’ exhibition centered on the work America: A Hymnal (2017), an immersive piece that explores 100 versions of the anthem My Country ’Tis of Thee, which underwent rewrites between the 18th and 20th centuries to support various causes. Here, the written versions are bound together chronologically in an artist book. Collins has burned away the sheet music notes with a laser. A sound work, installed in the room, relays six different voices singing all 100 versions at once—a cacophony, but a familiar dissonance, even so. The various melodies and lyrics remain recognizable. America: A Hymnal is currently on view at the Peabody Essex Museum, through 2024, shown in a gallery wallpapered with a new work of flocked flower silhouettes referencing floriography, or the symbolic language of flowers.

Installation view of “Bethany Collins, America: A Hymnal” (2023). Photo: Kathy Tarantola. Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA.

“I am interested in repetition. I’m always looking for the chorus that’s happening over time. Without that chorus, I can’t make sense of history. The repetition is sometimes an indictment, sometimes it haunts, sometimes it comforts.”

“Bethany Collins: Undercurrents” is on view at Alexander Gray Associates through December 16, 2023.