The art one sees as a child can have a profound impact on a future career in the arts—just ask Linyao Kiki Liu, a Beijing-based artist, collector, and former museum director.

Born in Beijing and raised between China, Australia, and New Zealand, Liu grew up seeing her family’s collection of traditional Chinese artwork alongside the work of the Western masters during her travels and time abroad, which together shaped her considerably international ethos and appreciation for artwork and projects that explore cross-cultural connections.

As one of Beijing’s most innovative on-the-rise art world personalities—who counts Angela Goldin and Klaus Biesenbach as friends and mentors—Liu is a multi-hyphenate professional who, at just 28, has worked in nearly every field within the art world and has finally found her calling as a painter.

We spoke with Liu about how she fell in love with art as a young girl, what she’s interested in creating these days, how she collects art and what she’s learned about collecting from her family, and more.

You grew up in a family that loved and appreciated art in many ways. Do you recall the first time you really connected with art as a child?

I wouldn’t call it my earliest memory necessarily, but probably one of my first attempts at engaging with art in an active way as a child was buying printed books about the work of the Old Masters. In China, we have this tradition where children are given red envelopes—small packets containing money for little kids—as a symbol of good luck, and I spent the money I got on those books. It’s kind of funny to think about because I was so young at the time. And then in terms of making my own art, I remember trying to learn Chinese painting in kindergarten. I remember painting with inks and thinking the works were really abstract.

What kinds of art-related activities did you do with your family? How did you engage with art altogether?

My family was never really into contemporary art, so I didn’t really visit the gallery spaces that I’m familiar with now. But I definitely remember going with them to auction houses. I was really young—I can’t believe I remember this—but it was definitely in the ’90s that China started our own versions of auction houses. Those houses would invite collectors to come preview the lots before they went on sale and I remember—because my family was interested in traditional Chinese art—going into the contemporary section while they were looking at the traditional work and seeing all this interesting art. I didn’t understand anything about it at that time because the formal qualities were so different from what I was used to. Observing those works was a totally different experience.

Linyao with her cat in Wutaishan, Shanxi, China. Photo courtesy Linyao Kiki Liu.

How was it different, and how did those differences resonate with you?

It’s just the colors, I think, that made it entirely different. In Chinese paintings, obviously we use ink as our primary medium and therefore our color schemes are black and white and grey, and darker tones, so suddenly your color palette expands and becomes more vivid. As a child, I remember thinking, “Who’s this artist?” And, “Who makes this clay sculpture out of a car-crash scenario?” I thought about how Abstract Expressionist painters layered paint. But it was really the color that stood out to me.

You’re a painter now. Did you take any art classes while in school?

Yes, all Chinese students are actually required to take art classes. And I think I had a good teacher in school, too. I still remember her because she sought me out. For high school, I studied in New Zealand and Australia, where the education systems were more liberal—you could choose the classes you wanted to take, and art was always in the mix for me. Of course, young students at that time were obsessed with making something that looked nice or pretty, aesthetically. It wasn’t until college that I began to think about art critically, in my own work and outside of it. I did a double major in art history and studio art at DePauw University in Indiana. I got a lot out of that experience and had great professors.

Who were your favorite artists growing up?

I loved Mark Rothko and Joan Mitchell. I graduated college in 2014, and my thesis examined the work of a contemporary Chinese artist, Cai Guoqiang. I think the latest works we ever studied were from the Modern period, so writing about contemporary artists was kind of radical then. They definitely were my favorites at the time. And I attended and worked at art fairs, too, in addition to regularly going to every museum I could visit, so I kind of took every opportunity to see these artists.

Installation image from Liu’s 2018 exhibition of painted works “Yes I Love You.” Photo courtesy Liu.

Speaking of: how would you categorize your artwork in college, and how would you say your practice has changed over the years?

I think it’s definitely changed a lot, although I’m still an extremely emergent artist and I must continue to change my style and push myself. In college, I didn’t do any installation work but then, after that, I started pursuing that medium and it’s been really interesting to play with the idea using readymade objects to provoke people because they have preexisting, everyday relationships to certain objects. That’s one way the work has evolved. I think, for painting, my college professor John Berry in the painting program was such a gift to me that every time I look at my work, I think about how he critiqued them and how he would notice things that changed in my style. He could see beyond what I could see in many ways, beyond the surface, and I tried to learn from that.

What would you say interests you most, as an artist? What’s the last body of work that you completed?

In terms of what interests me, I think universal human emotions do most—the things that we all share. We all happen to be born on this earth and that means we all share a similar kind of sentimental karma. Especially now, this idea of a collective destiny has never been clearer, in a way—we’re all facing many of the same things. Emotions are a universal language to reach people from different cultures. Of course, painting itself also interests me—painting as language, as representation and, at times, as a visual puzzle.

In terms of my work, I’m at the end of an installation project called “Stay with me for a long bit longer.” It’s a box that simulates the wind speed of a place, imitating a natural phenomenon that I am dwelling on but which can’t be preserved.

And what are you working on now?

Right now, I’m doing my master’s program in visual media anthropology. It’s an online program that’s based in Berlin. I’m also working on some small video pieces for it, which I’ve never done before. And I’m always working on my paintings, and going back to the subject of intimate relationships and experimenting with the bounds of realism and abstract representation.

Who are some of your art world advisors and mentors?

Beyond my college professors, I feel so lucky to have formed close relationships with some pretty brilliant mentors and art-world peers. I made friends really quickly, almost too quickly—in a way it’s kind of nice to have a break from the art world, because it can be quite overwhelming. But Klaus Biesenbach, for example, has been a great support and source of influence. So has Peter Eleey and Angela Golding. The whole PS1 team came to Beijing earlier this year. We were together at the beginning of all of this, and they’re all such great human beings and I feel really lucky to have them as friends and teachers.

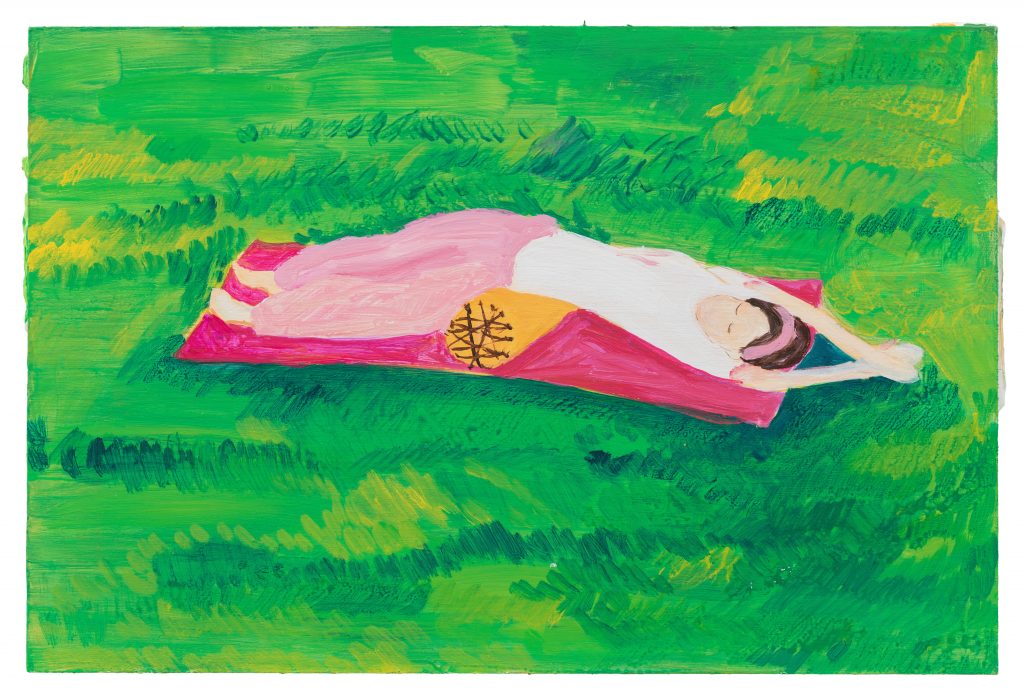

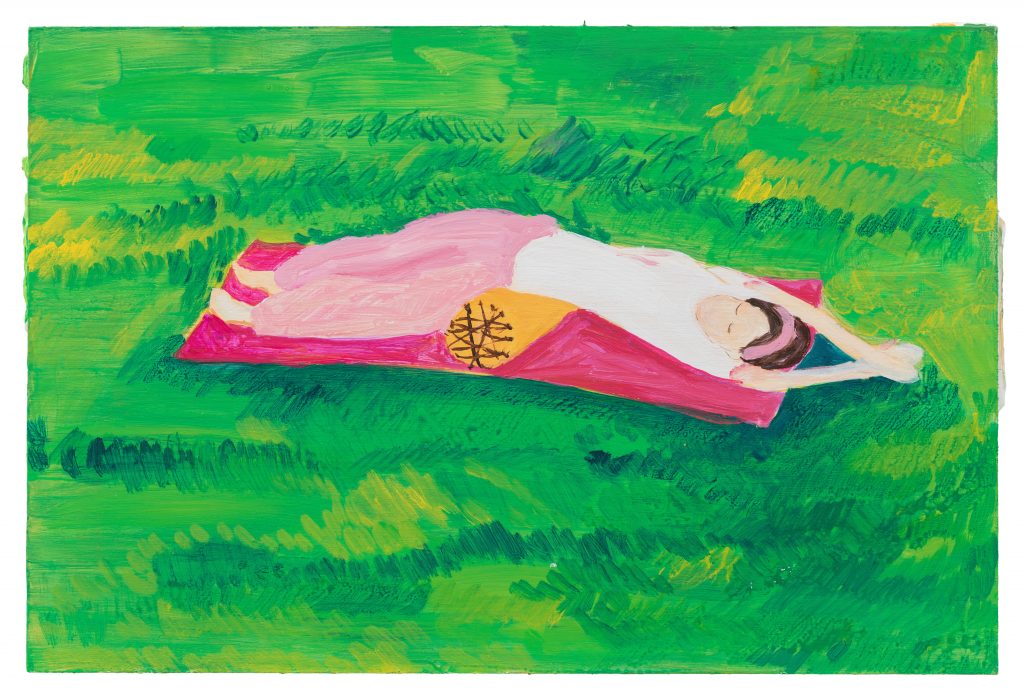

Linyao Kiki Liu, “Untitled” (2019). Photo courtesy the artist.

For a time you were running the Sishang Art Museum, a contemporary art museum that your family began in 2010. Tell me a little bit about what you learned from working in a museum position and maybe how it’s influenced the arc of your art career.

Unfortunately that museum is closed now, but we started it initially because my mom had a vision of opening a sculpture museum and at the time, she was quite new to the contemporary art world. And in many ways so was I—I graduated college just a few years later. Funnily enough, right now I’m involved in Harvard University’s museum program despite the fact that I’m not in the museum field anymore. Still, I think it’s important knowledge to have because they answer a lot of questions that really frustrated me when I held a museum job. And I think it took me a while to make the space contemporary and make it hold value for the community and not just something that showed people beautiful work and told them what to think about it. I don’t think I’m in any position to tell an audience what is beautiful and what is not. I’m just trying to provide a platform for artists and their shows to showcase certain sentiments about the world that everyone can somehow relate to. It’s more about community for me. And I think that’s something that, as a concept, has always really intrigued me and has been my driving force.

I think people are thinking about those themes a lot right now—accessibility to art and what the roles of museums and galleries are when presenting artwork to the public. Do you think about this idea, in terms of what the museum or gallery model of the future looks like?

I think that’s too broad a question for me. I don’t have a gallery of my own, so it’s not something I can totally relate to. But it’s interesting that I worked at a museum for a couple of years, and now I’m studying how to run one. So to a degree, yes, I think about these themes. But I think what interests me, especially this year, is not how these questions manifest on the organizational or institutional level—it’s the personal level that interests me. It’s really about confronting how we think about art on a day to day level. Oftentimes, we’re talking about art and seeing it with people who are not in the field or in the art world. We’re talking to everyday people, so the question I’m focused on right now is, How do we not pass on our judgement to the everyday museum-goer who may not have the same context or knowledge as someone in the art world? How do we make art for everyone and revise the ways in which we assess it?

I’m not saying necessarily that we should all use a post-modern perspective to approach art, it’s just we should try to respect and accept that there are other forms of art that people put their hearts and souls into that are not really accepted in the art market. That work also has value and should be viewed as a means by which to understand another person’s perspective. That’s the personal level that I think we need to focus on more. It’s kind of like if you go see a show with a friend who knows nothing about art and she falls in love with some really commercial-looking painting of a red flower. You’re compelled to write it off, but maybe we should be trying to engage with it and learn its value and talk about it in another way.

Do you have any predictions for what the art world will look like in five years? Or what do you hope it’ll look like?

I think there might be something Dadaist about the art world of the future. [laughs] I don’t know why I’m saying that, but I think with all the anti-consumerism, anti-globalization, and the state of relationships between each country, I think there could conceivably be a small wave or return of Dadaism. My work doesn’t really speak to this moment, but I would love to see interesting art—maybe that’s internet work—that exposes how crazy everything feels at the moment.

Installation image from Liu’s 2018 exhibition of painted works “Yes I Love You.” Photo courtesy Liu.

Who are some emerging or young artists that you have your eye on right now that you feel like people should know about?

This young artist Tong Kunniao is great. He has been very active and, in a sense, ruthless. Many young artists, including myself, are struggling with the conceptual aspects of representation, but I think he has a kind of young, experimental energy that many of us artists lack.

I also think people should know about this exhibition-project organization called Wall On Wall—they make photo exhibitions about border walls around the world.

And I love the environmental activist and artist Sarah Sutton. I am enrolled in her sustainable organizations class right now and I think her work is extraordinary. She’s a really inspiring figure.

What have you learned about art from your family? Whether it’s about appreciating art or collecting or being an artist yourself, is there any advice that your family has given you that has been valuable to you?

As an artist, I feel I’m not influenced by the collections of my family—but the interesting part is that my mom always says otherwise. She feels that my works—or my taste, rather—is, even though my medium is acrylics and oils and my parents collect a lot of traditional, ink-based work. She always says that the way I utilized space and brushwork in my composition “Liu Bai” (“leave blank”) has traces of traditional Chinese painting. I guess you take everything with you, though, right? You can’t separate yourself from what you’ve come from.

I don’t know if I agree with her assessment, though. But it’s something that keeps coming back to me. I think going to museums together as a family was something that was really normal for us so that may have influenced me and my style. It was more about this idea of seeing art together that was normalized. I’m also very privileged that I was able to travel from a young age. In elementary school, I was traveling to Italy and France to see the masters of the Renaissance, so I’m very lucky for that.

Tell me about the art you collect.

I collect art myself on a small scale—it’s such a joyful activity. My collection isn’t limited to medium, region, or time. I have also only been collecting for a few years, and I can’t say I’d have clear guidelines or that I’m focused on particular interest groups or topics.

Do you have any advice for young collectors like yourself?

Collect what you love! If you want to collect because of financial or investment reasons, it’s still a gamble. So you might as well just collect works that touch you and support the artists whose work intrigues you. That kind of sentimental value cannot be measured by the binary opposition system.

Linyao Kiki Liu, “Untitled” (2019). Photo courtesy the artist.

Looking ahead, where are you hoping to travel to when the world opens back up again?

I want to see nature! I’m able to see nature here thankfully, Beijing is two hours away from the mountains, but I’m also missing the beauty of seeing art in person. Looking at art on a small screen constantly is claustrophobic. I don’t want to be cheesy, but I really do miss the beauty of seeing art outside of that format. And quite frankly, I just miss beautiful art in general—don’t you?

Absolutely. Have you seen any good online shows worth checking out?

Yes, I have. Beijing has a really interesting gallery called White Space—they are the first group gallery to do online shows in interesting, innovative ways. I think they made the virtual experience really hands-on and different because they rebuilt their gallery model and curated a show within this virtual reality world with the artist Wang Tuo, whose medium works really well for the medium of an online exhibition. You can have this virtual experience of walking into the gallery and seeing how they lay out the shows, and this video is really well formatted for your phone or your projector or your TV and I thought that was really cool. And they just opened this other show of a young female painter and they completely altered the space to show her work.