Art World

10 Little-Known Andy Warhol Facts: His Biographer Busts Myths, Solves Mysteries

When did he change his name? How did he first encounter the avant-garde? Read on.

Andy Warhol must be the best-known artist of the Western world, but it’s amazing how many misconceptions still hover around him, and how much of his story still goes untold. We’ve asked Warhol biographer Blake Gopnik to give us 10 little-known facts that help explain who Warhol really was and what he really got up to. —The Editors

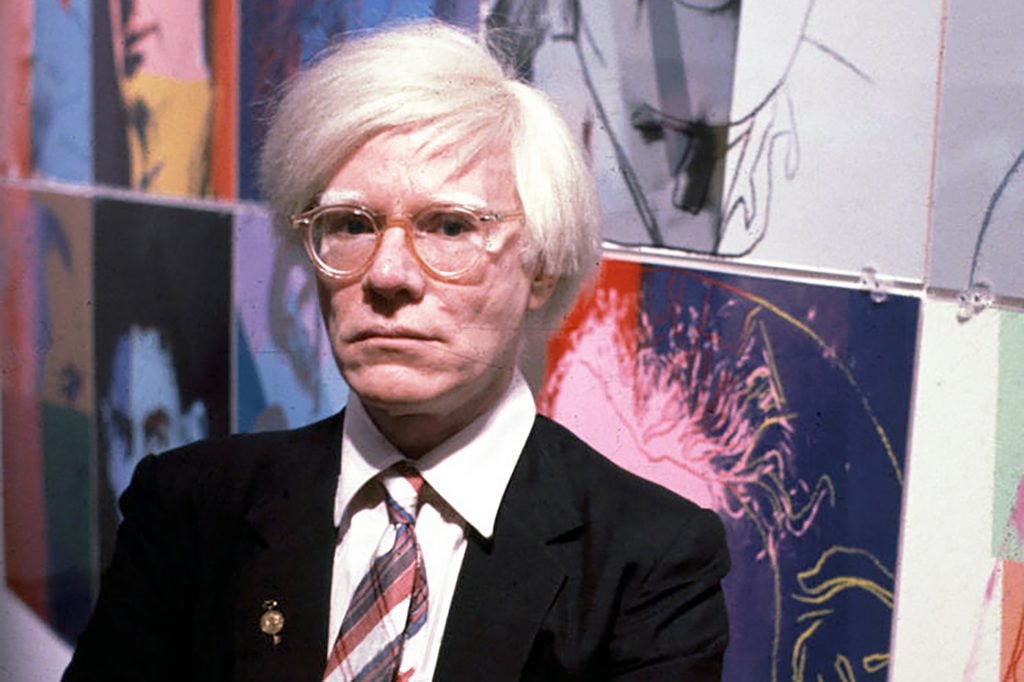

Pop artist and film-maker Andy Warhol. Photo by Express Newspapers/Getty Images.

1. Here’s the story, as normally told. In the summer of 1949, when Andrew Warhola arrived in New York from his native Pittsburgh, almost the first thing he did was lose the too-ethnic “a” at the end of his last name. It was the beginning of the self-creation that was such a central part of his career as an artist . . . except that it wasn’t. He’d already removed that “a” when he signed a self-portrait he’d painted at the age of 15 or so, some five years before.

Warhol’s play with his public persona seems to have begun almost as soon as he had one. In college, another self-portrait shows him with white fingernail polish and the limpest of wrists, wearing a pink corduroy suit. In yet another painting, he portrayed himself as a nude little boy with Mary Jane shoes and his finger stuck up his nose.

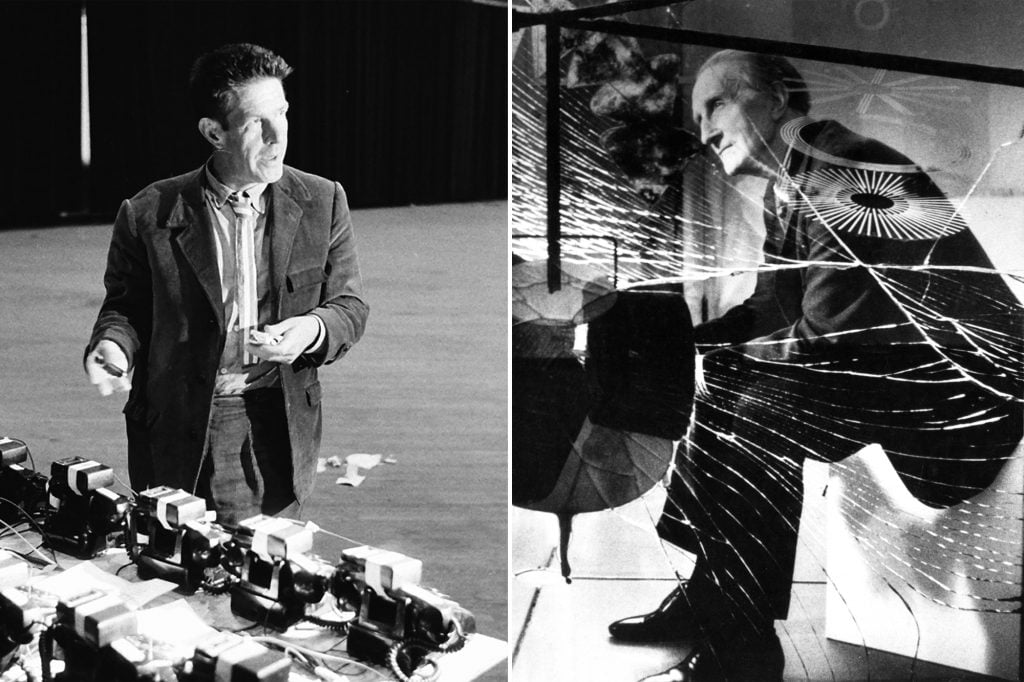

Left: John Cage in 1966. Right: Marcel Duchamp in 1965. Photo: Robert R. McElroy/Getty Images; Mark Kauffman/Getty Images

2. Warhol’s best art comes straight out of the conceptual experiments of John Cage and Marcel Duchamp, which were beginning to rule the New York avant-garde in the late 1950s. Amazingly, Warhol had already been exposed to both when he was barely in his teens, early in the 1940s, at the remarkable Outlines gallery in Pittsburgh.

Outlines brought Cage in to lecture more than once, and it showed Duchamp’s Boîte-en-Valise, the anthology Duchamp made of all his earlier works in miniature. (Outlines’s founder owned a deluxe Boîte.) There are even hints that the teenaged Warhol stole one of the miniatures, only to later return it.

An installation view of ‘Becoming Andy Warhol’ at UCCA Edge, Shanghai. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

3. For all the tales of Warhol eating Campbell’s soup, daily, he in fact had gourmet tastes. One Thanksgiving in the 1950s, he cooked “pheasant under glass” instead of turkey, he was a regular at one of New York’s first Japanese restaurants (the receipts survive) at a time when most Americans still considered sushi a bizarre barbarity, and he consumed caviar by the spoonful, when he could.

Warhol was never much of a true participant in popular culture, despite the subjects he chose for his art. He always came at the popular from the vantage point of the West’s “high” culture—in art and in all things gustatory.

Andy Warhol, left, with Lou Reed, circa 1980. Photo: Richard E. Aaron/Redferns/Getty Images

4. We all know Andy Warhol, right?—that 97-pound weakling with the girlish blond wig. In fact, he was already a gym rat in the 1950s, before weight training went mainstream. He loved to arm wrestle, and even after getting shot in the abdomen, he could do 42 push-ups. (There’s video of it.) “He’s like a demon, his strength is incredible,” the (much younger) rocker Lou Reed said, recalling how Warhol had once pinned his arms during some kind of roughhousing.

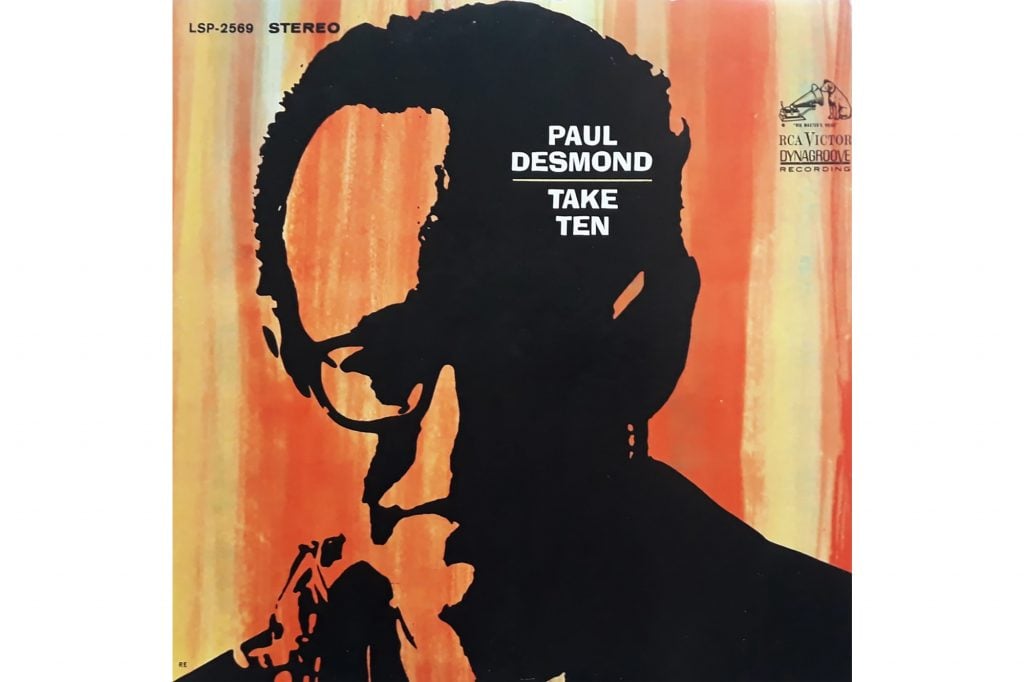

Paul Desmond’s Take Ten. Photo: Sony Legacy

5. The usual story is that Warhol’s first silkscreened portraits came late in the summer of 1962, with his epochal images of the late Marilyn Monroe. Or maybe with the portrait of Liz Taylor that his dealer Irving Blum had already mentioned in a letter that June?

Nope, neither of those.

In 2019, the Belgian collector Guy Minnebach discovered a vinyl album of jazz great Paul Desmond, saxophonist for the Dave Brubeck Quartet, whose cover is a portrait of Desmond photo-silkscreened by Warhol in April of 1962. That means Warhol’s Pop Art depended on—appropriated, really—a method he first developed in the commercial commissions he was doing his best to hide from the art world at the time.

Eighteen months before Warhol had done any portraits at all, his very first works of Pop Art, based on comics and ads, had started life as lowly props for a store window. Warhol only turned them into “art” afterward, the way Duchamp’s urinal became the sculpture called Fountain.

Andy Warhol, Jane Holzer [ST144] (1964). © The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, PA, a museum of Carnegie Institute. All rights reserved. Film still courtesy The Andy Warhol Museum.

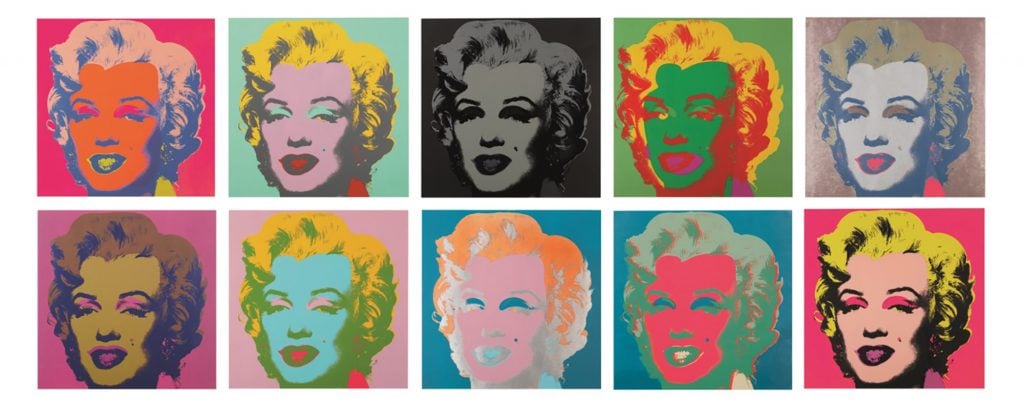

Andy Warhol, Marilyn Monroe (Marilyn). Photo: Courtesy of Christie’s

7. Warhol is often said to be a “great colorist,” but he regularly got other people to choose the colors for his works. In 1967, his friend David Whitney chose the colors for his first print portfolio, of 10 identical Marilyn faces, and those colors are all that tell the 10 prints apart. At his best, Warhol wasn’t really interested in the traditional “aesthetic” virtues that some people—especially sellers and buyers—try to spot in his work. By getting other people to choose his colors, he was adopting the chance-based procedures of Cage and other conceptualists. In Duchampian terms, Warhol gave us the anti-retinal parading in retinal drag.

Unknown photographer, Andy Warhol and his Christmas tree in the Factory (1964). Courtesy of the Andy Warhol Museum.

8. For something like 45 minutes in November 1985, keen eyes might have noticed a certain celebrity artist on a New York street corner, wearing Santa gear and ringing bells for the Salvation Army. It’s a nice, homey image that goes against the vampiric reputation that Warhol still has in some quarters.

On the other hand, it’s easy to read too much into the “good works” that Warhol, the “good Catholic,” is supposed to have turned to in his final years. It added up to no more than a handful of sessions as a soup-kitchen volunteer, as suggested and then arranged by people in his retinue. Statements like “I believe in death after death” and “When it’s over, it’s over” probably give a more accurate window into Warhol’s (un-)holy side.

Andy Warhol, Jed Johnson and Archie. Photo: Courtesy of Christie’s

9. Warhol, the great counterculturalist, was actually wedded to pretty traditional notions of romance and the domestic—even if, as a gay man in an intensely homophobic world, he was mostly kept away from conventional family life.

In the 1970s, when he was at home with Jed Johnson, his partner for 12 years, he liked to entertain in the cozy, old-fashioned kitchen he had installed in the basement of his grand house. A couple of times, he talked about adopting a child, and he was always great with kids.

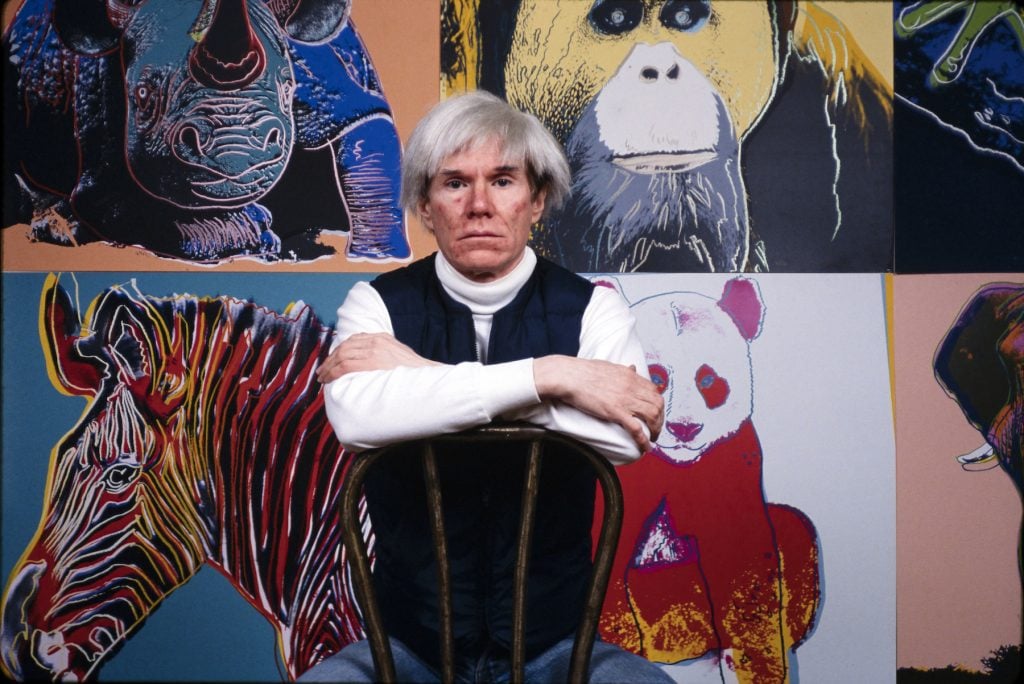

American Pop artist Andy Warhol sits in front of several paintings in his “Endangered Species” series at his studio, the Factory, in Union Square, New York, New York, 1982. Photo: Brownie Harris/Corbis via Getty Images.

10. In April 1988, at Warhol’s estate auction, everyone noticed the wacky things he’d collected: Cookie jars and piggy banks and Bakelite housewares. What got much less attention, because almost none of it ended up in the auction, was the serious avant-gardism he also collected. According to gallery receipts that survive, he bought a very early “prop piece” by Richard Serra, a “relic” from a performance by Chris Burden, and a radio work by Keith Sonnier. That art was the best company for his own, which was never really the Pop-y, audience-friendly stuff it got billed as.