Art World

Why Artist Lois Dodd, One of Our Keenest Observers of the Everyday World, Has Been Painting Windows for 50 Years

The 90-year-old painter is the subject of a new book and exhibition in New York.

The 90-year-old painter is the subject of a new book and exhibition in New York.

Faye Hirsch

Of the many recurrent observational subjects that Lois Dodd has treated throughout her career, none has been more conspicuously ongoing than that of her windows. Among her earliest memories are of gazing out windows in her childhood home in Montclair, New Jersey. She told Ada Katz,

I can remember looking out of the window in summertime and seeing large trees, the front yard, etc. … You know, when you get visions of yourself and the house, looking out, it’s generally summertime. My next oldest sister and I—I’m the youngest—slept in a porch with eight windows with eight black window shades, or green, with all the little pinpricks and all the images you think you can see.”

Dodd’s recollection of youthful summer days and nights in Montclair gives pride of place to windows, as she considers both the phenomenological experience they offer and what is extrapolated on the level of imagination. In her recollection, she refers to her sister, and to sleeping with her in the porch, but she begins by speaking of the experience of looking out the window at the human-touched nature represented by a front yard, and the essential impression of summertime. At night, pinpricks in the shades spurred fantasy. Dodd has spent much time indoors looking out of windows to find her content, and one feels her presence and solitude—her subjectivity—most particularly in these works. Indoors, she may record the inclement weather that has prevented her from venturing forth—snow or rain, transformed from hindrance into content. Equally, as she wanders about, she has frequently settled on windows seen from without, drawn to the grid and flatness they provide as a matter of course, and captivated on longer engagement with the myriad reflections and imperfections from which she selects what is worth recording. “In her window paintings,” wrote John Yau,

“the artist establishes a palpable bond between the work’s two-dimensional, rectangular format and the window as a transparent, penetrable plane. It is a kinship she uses to formally explore the tensions and pressure points that exist between surface and depth, and to underscore the link between the work’s status as fixed object and the painting’s state of immanent change.”

Barn Window With White Square, 1991. ©Lois Dodd, courtesy of Alexandre Gallery, New York.

Windows are a longstanding motif in the history of Western art, with a lineage stretching back to Dutch baroque painting and beyond. As a subject, windows began proliferating in the first decades of the 19th century, depicted within the interiors of artists’ studios as an emblem of the artist’s position vis à vis nature and the world. German Romantics, in particular, returned to genre painting, especially interiors, as an alternative to the grand history paintings of the immediate past—and to the seemingly failed themes they had championed. Within dark, spare rooms we find ourselves gazing at landscapes through one or more windows in paintings that are “neither landscape, nor interior, but a curious combination of both,” as Lorenz Eitner wrote in 1955 of those Romantic pictures. With Dodd—hardly a Romantic in any obvious way—we can add another element to the mix: neither landscape, nor interior, nor abstraction, but a “curious combination” of the three. Dodd was among those who, enamored of Abstract Expressionism—arguably the grand manner against which a new generation of American painters was measuring itself—had managed successfully to shift into a more intimate form of representation, bringing along at least one lesson of the earlier, dominant school in the form of a staunch faithfulness to the picture plane. Indeed, it was the readymade grid and inherent flatness of a window seen from the outside that first drew Dodd to the subject, in 1968—the date of her first window.

We have already seen how, in 1967-68, upon returning to the city after a summer of plein-air painting, Dodd spent many days looking out of her 2nd Street window at the graveyard below, recording the grassy court along with its surrounding buildings and their cast shadows. The following summer, returning to Maine, she noticed the simple, four-paned windows of Cushing’s Acorn Grange at the end of Hathorne Point Road, and proceeded to record them on small Masonite panels. In the following years she moved on, apparently painting every window in the vicinity and scaling up both in size and ambition:

The first two small windows [1968] were Cushing Grange Hall. . . . Then I shifted over to this vacant house. … That’s where I did the first one that was somewhat enlarged. [The paintings] got a little bigger. Then I [shifted] over to my house and I started moving around the house painting all the windows there. … The next summer when I got back I went to look at my little garage building that I was painting and the window up high in the peak was busted. … There was a nice pattern of broken glass and a reflection as well.

By 1971-72, she had begun making some of her windows life-size; in those two years she produced at least four such paintings. “At a point,” she said, “I just couldn’t dream of squeezing [the windows] onto something small. … If it was terribly small with not much happening then I would take a small [Masonite] panel out and do that, but the minute I could see that there were two or three levels of things occurring, I felt like I needed something life-size.” Small (on Masonite) or large (on linen), Dodd’s windows are of many kinds: singular, observed from outdoors or within a room; multiple, seen from outside, night or day, punctuating the facades of city buildings or simple homes in Maine and New Jersey; broken, in derelict or abandoned houses and barns in the country; opaque and unrevealing or highly reflective, with confusing lines of sight; and, sometimes, opening onto landscapes in limited views—the kind Dodd prefers, even when there is no framing window. There is one continuity, however: out of dozens of paintings of windows, only two contain images of a human being—and those two are Dodd herself.

First, however, was the grid. “When I first started,” Dodd told Yau in 2011, “[I thought] ‘Wow, there’s this frame and all I have to do is fill these rectangles,’ and, if you put it in the right place, it’s all very organized, if you can get your head in the right place.” For Dodd, the window became a readymade composition that allowed her to move the painting along quickly.

In the windows, she discovered a natural restriction that in fact allowed her great freedom to explore a range of effects. Within a steady geometry, color and movement were set free. She “wants to see—and wants the viewers of her paintings to see—both the evanescent and the relatively stable aspects of things at the same time,” wrote Barry Schwabsky. In Blue Sky Window (1979), the geometry is stable—or is it? Shadows play across the window’s white frame, rendered in rose, gold and gray, giving the lie to the fixity of an apparently transcendent blue sky—a view seen from below, as Dodd lay waking.

As Dodd has recalled, it was soon after she began painting the window as a subject that she grew interested in reflections as much for their propensity to capture the effects of time and change as for the formal possibilities they presented:

I’m painting this window, and the glass was there and behind that was the curtain. So it was like painting the whole thing in reverse. Then, as I was standing there, I could see the reflection of the barn, and then a cloud came drifting over so that was just perfect. All these little things that would change it. There is still a possibility of something moving, even though it did look static. So I like that, too. I enjoy being out there and something occurs in this very quiet way. Nothing is fixed. It’s always changing, even while you’re working.

Especially intriguing to her were the opportunities to contrast concrete objects and more ephemeral visual effects—what we see in the glass as opposed to around and through it—but within a larger conceit that all, when said and done, is paint. The mini-landscape visible through the window of the far wall of Elliot’s Shack summarizes the woods beyond in a few strokes, positioning the vertical trunks in a staggered row—a mere swatch of woods that stands for the whole. “It was all such a revelation,” she told me, “seeing all this stuff [reflected] behind me and the ‘real’ landscape beyond.” Apart from its potential for abstraction, the window became a pretext for bravado effects uncustomary for an artist given to reticence in her painted manner. Striking in this image is the contrast in focus between the reflected woods and those in the small window. In the latter, we get very little foliage, as the view is cut off below the treetops; in the reflections, we are given leaves exclusively, and summarily, as the sight line is higher. Moreover, what is closest to us—the reflection—is treated as mere daubs of paint, foliage blurred by the glass. What is furthest away—the landscape in the small window—is painted with clarity. Add to that the hard-edge treatment of the foreground window’s frame and its sharply cast shadow, and the result is an optical and psychological immersion that undermines the clarity of the subject and our place in relation to it.

Cleanly delineated in framing and composition, the windows operate on two levels. On the one hand, there is the plain empirical description of American realist painting—we get what Dodd sees—just the facts, as it were; on the other, a sly undercurrent of modernist abstraction, European style: Mondrian and Malevich in grids and squares, Cubists (Robert Delaunay, for example) in reflections. Night Window—Red Curtain (1972) shows the interior of a Cushing window cracked open to allow the night breeze to enter. The bright red comes as something of a shock in the context of the limited palette of other large-scale windows. In fact, Dodd told me, she was absolutely “crazed” to use red, a color she never found in nature; she had not begun painting flowers. (The same red curtains, laundered, became, five or so years later, the frequent subject in paintings of clotheslines.) Here the red curtains seem to stir a little, an impression conveyed in the sheen of light playing across their folds; their bottom hem creates a lively shadow on the yellowish wall, of a color that feels faithful to tungsten lighting. So far, it’s a night in Cushing, Maine, a quotidian moment made rather grand by the lush red curtains, a kind of theatrical immanence. At a point, we become intrigued with half-concealed reflections peeking from dark panes; they must reflect objects behind the artist, but it’s impossible to tell what, exactly. Instead, they register as mini-abstractions within the larger representation—hints of still-lifes by Braque or Gris, artists whom Dodd admired.

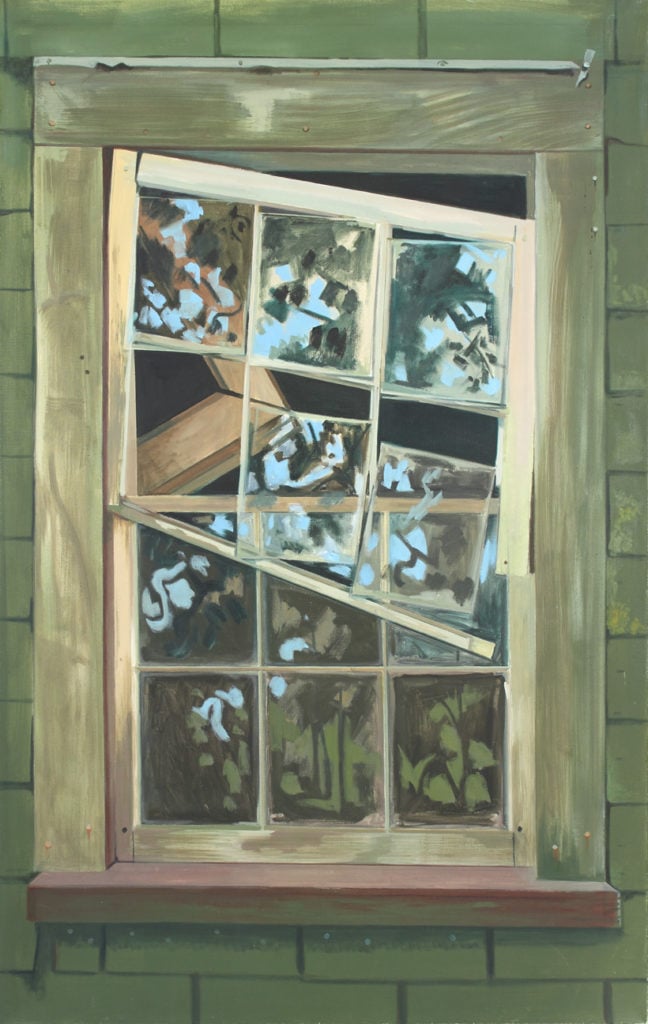

Falling Window Sash, 1992. ©Lois Dodd, courtesy of Alexandre Gallery, New York.

Dereliction has provided Dodd with some of her best windows. “In Maine you see these amazing ruins,” she told Barbara Shikler in 1988. “They could mean ruin like Roman ruins, except they’re our ruins.” Whole buildings lay in partial collapse by the road, as in a sagging hulk she found on the way to nearby Thomaston and painted several times (e.g., Back Building Front, 1986). Understandably reluctant to sit in front of occupied dwellings, Dodd has often settled on such abandoned structures, which, especially in their windows, offer added seductions in marks of neglect. In Falling Window Sash (1992), the kind of reflections we saw in View Through Elliot’s Shack come tumbling down, as Dodd unites a falling sky with a fallen strut or beam within. The surrounding window frame and shingles lock the chaos in place. Broken panes and the dark interiors of abandoned buildings permit Dodd to collapse foreground and background into the single flat plane she prefers. So much the better if, through the room within, we are able to glimpse that window on the opposite wall, further baffling recession as it is brought to the fore. The visual puzzle is relatively straightforward in a work like Barn Window with White Square (1991), a life-size view of the exterior of a broken window, four panes intact and the rest destroyed. Blank openings are painted an opaque black to indicate an unfathomable interior space. The exterior weathered wood frame is coextensive with the picture edge, square in shape, and that overall square is echoed just off center in a tiny bright white square nestled in one of the open panes. This we are able to read as a window on the other side of the room, and Dodd’s inclusion of it brings the merely imagined back wall in which it is situated to the very surface of the painting, where the white square sizzles in the grid at the front plane. The actual size of a window, the work carries a trompe l’oeil impression of rotting wood, rustic nails, and, on the glass that remains, an opacity of soot from years of neglect. Dodd sets up a dialectic between an implication of distance and the optical immediacy of design, between the readability of a place and its concrete abstraction.

Sometimes reading the image can present a challenge. At an exhibition in winter 2017, the artist and a small group gathered in front of her 1980 Masonite painting Window—Ochre, Black and White, at which they closely peered. Everyone, including Dodd herself, was at a loss to locate the constituent parts of the image, which is rendered in the low-key palette of the title. The elements are a broken window, seen from without, and a four-paned window on the opposite wall within, giving onto the outdoors on the other side of the building. Behind us is a great hulking mountain, reflected in the window, but the mountain merges with and disappears into the interior gloom; similarly, a silhouetted tree, probably between us and the mountain, is also reflected, but it is difficult to tell where its reflections fall, exactly, and whether the remaining glass in the pane is cracked or missing entirely, or if changing light is the cause of the confusing reflections. Despite its subdued palette of brown, gray, ochre, black and white, the painting is hardly “minimal.” With its loose brushstrokes and summary description, it compresses solid surface and reflection into complex patterns of muffled color and light. Dodd’s loose rendering of the image amplifies the sense of flux, as if the chaos of nature and entropy is barely contained.

Dodd rarely succumbs to bravado, yet she comes close in another optically challenging work of around the same time, The Painted Room (1982). Here she seems to revel in the pleasures of illusion, painting a summer window in the Cushing house framed by yellow curtains and a forest mural that she had created on its surrounding walls. At a human scale of five feet in height, the painting implicates our bodies within the painted room, which remains to this day a fixture of Dodd’s Cushing home. “The room needed to be painted,” she told me. “I was patch plastering and decided to paint a blue sky. Then the next summer, I went to paint [the woods] on the other wall, where the wallpaper had just fallen off. I used a cheap wall paint as medium and pigments I had left over from Cooper for the colors.” Through the window, we glimpse summer foliage on a sunlit day, the light so bright it flares white on the curtains. The fact that the window is executed in a style identical to that of the surrounding forest, with its red floor and silver-tinged trees, leads to a confusing moment as we try to disaggregate the parts. Dodd provides a clue to her trompe l’oeil in the form of an unlit bare bulb hanging from the ceiling, a detail that helps separate the “real” architecture of the room (and by extension the “real” window) from the mural. In reality, of course, it is all paint, and one of Dodd’s best deceptions—striking an exceptional position in making us notice the painting’s artifice and, by extension, her skill. “Tromp l’oeil, in its near-duplication of a visual experience of the real object, always unveils its illusion so that we appreciate the skill of the art,” wrote Caroline Levine in a study of John Ruskin’s attitude toward tromp l’oeil.

To achieve the “minimal”—an aim that Dodd shared with her Minimalist contemporaries, though theirs is a movement with which she is never associated—it came down to reducing and culling the visual information present before her eyes, a process that may involve some telling exclusions. As she told Pat Mainardi in 1973, the problem of what to do with herself first came up in the very first painting she ever did of window reflections, Reflection of the River (1971):

The more I looked the more I saw. Pretty soon my own reflection was there, too, but I chose not to include that. … If I stood directly in front, the reflection was there. If I chose to include it the complications of the fractured reflections created such a complex image that I would need a much larger canvas to work it out. And then I would not be able to work directly.

In spite of the fact that, as she told me, she almost always sees herself in the windows, she has included her own image (as far as I know) only twice, in 1971—in a small Masonite self-portrait, in which she is wearing a rather merry yellow sunhat, and again (also with the sunhat) in the larger Self-Portrait in Green Window. Here she places herself nearly at the center of the image, pinned as it were beneath the crossbars of mullions, with most of her body—arm extended as she paints—located in the lower left-hand pane. Because of the usual confusion of sight in such works, one has to look closely to place her, apparently standing on a lawn backed by pines. Also behind her (or is it within the room behind the window?) is some kind of structure that serves further to lock her into place. As she tells the story, it was only toward the very end of painting the picture that she noticed a tall single goldenrod standing just in front of the window; seeing that its flower was the same color as her hat, she opted to include it, along with a bit of its shadow and reflection. Its presence is as conspicuous as her own, and indeed we are tempted to link the two—the slim, bonneted artist and the skinny, bright-capped weed. It is a companionship of sorts between the self-effacing Dodd and this common New England wildflower. Meanwhile, the chromatic intensity of chartreuse shingles and window frame, which along with the deeper, shadowy blue-greens of the pines give the painting its title, never strays from believability. During a public conversation between the artist and myself in March 2017, Dodd expressed discomfort about her representation in the work, saying she looks “a little goofy.” Few would agree. The rarity of her self-representation encourages us to consider most particularly its presence here and its absence elsewhere. In fact, she is always present, if not literally. There is a sense in these lonely windows of an optical consciousness that places the artist within them by default. And more than that, it establishes an implicit relationship with the viewer that is often quite intimate. In Dodd’s windows, we are positioned in her place—as the eye that is both artist and viewer, maker and receiver.

From the paintings alone, one might never know that Dodd is a sociable being who enjoys painting with others. In the case of the windows, however, we surmise that she is indeed alone: and the work generates an overwhelming sense of solitude. As the artist has aged, challenging her mobility—particularly in winter—her views out of windows have increased in number. Mostly these are small-scale Masonite panels depicting inclement weather outside her Blairstown and New York homes. Less interested now in trompe l’oeil or bravado, Dodd discovers extraordinary effects and variety in her attentiveness to immediate conditions. Subtle shifts in light and color indicate specific times of day and year, though the seasons pass in seemingly tranquil oblivion to any marker of contemporaneity. We could be in another time, or now; her homes are aging, the windows old-fashioned sashes. Every small element, every choice, counts for something in these, the most intimate of Dodd’s paintings.

We guess that it is fall in Pink Geranium + Window Lock + Ochre Tree (2011), for, outside the window, a tree’s leaves are brown and gold. Dodd brings us in close to the window, so that we see only the main horizontal crossbar and its latch in shadow. Branches structure the dense screen of foliage outside, echoed in the delicate stems of the top of pink geranium near at hand. Sunlight is borne in the pink-white highlights of the flower, and in a single thin line that stretches across the edge of mullion and latch, and in patches that set off the ochre in the tree. The closely cropped view allows room for just one. In Rainy Window, we are shifted slightly to the right, a view that admits near the left edge of the painting the vertical risers, jogging from bottom to top sash. This careful, efficient framework stands in contrast to the view, toward the light, spare foliage on a tree blurred by rain. Splatters on the glass are thick, highlighted in white, perhaps the last drops of a shower through which the sun has begun to break. One can almost hear them plashing on the glass—or smell the wetness of an early fresh spring. Like Dodd’s memory from childhood, the view is specific to her, but we, too, can recognize the kind of day, the kind of weather, and join her in this very private moment.

In Roof, Tree, Window Frost + Snow (2015), the winter scene from the second-floor window in Blairstown is unobstructed; the tree whose foliage we see in earlier paintings, like February View (2011), has been cut down, and Dodd chooses to leave out the window’s mullions and latches. In fact, we might not even know we are looking out of a window but for the patch of frost clinging to the glass on the left. There is just enough warmth on the inside, perhaps someone breathing. That is the clue, something like the lightbulb in The Painted Room, which reveals where we are and how we are seeing what we see. It is snowing enough to render the distance vague; snow sticks in a jagged patch to the roof across the way, in lively counterpoint to a tall bare tree that stretches upward against a white sky. Not so very far away from where she grew up, Dodd looks out a window and notices, and we join her in a quiet companionship.

This piece has been adapted from the book Lois Dodd by Faye Hirsch (Lund Humphries, 2017).

“Lois Dodd: Selected Paintings” is on view at New York’s Alexandre Gallery through January 27.

Blue Sky Window 1979. ©Lois Dodd, courtesy of Alexandre Gallery, New York.