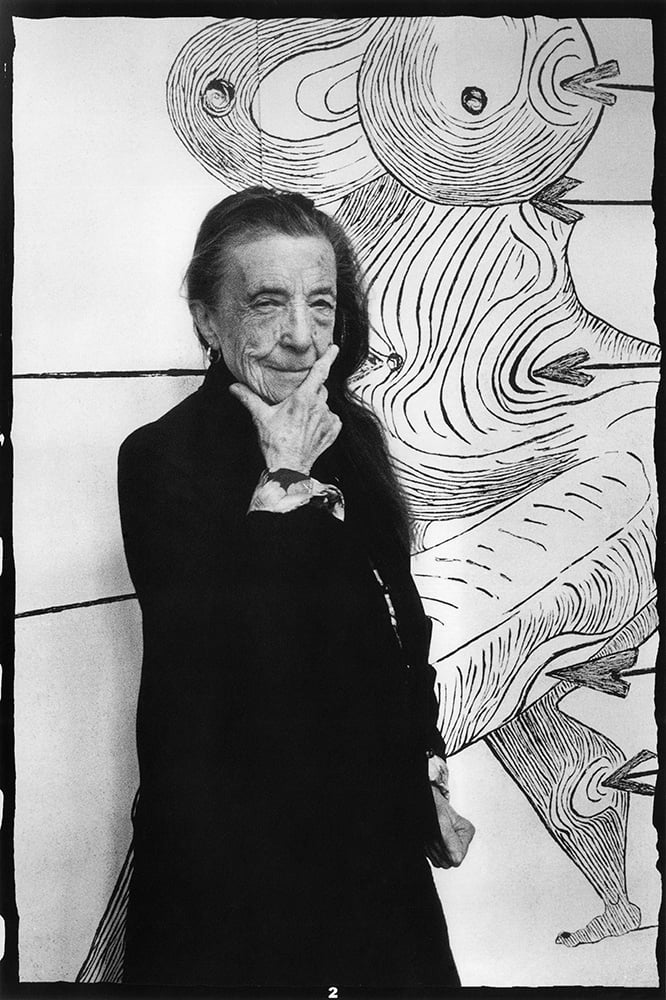

Louise Bourgeois is best known for her haunting, deeply personal art—but few realize that the beloved French sculptor was as prolific a writer as she was an artist. When she died in 2010, Bourgeois left behind shelves packed with diaries and boxes brimming with sheets of paper marked in her elegantly precise cursive. Now, eight years after her death, her foundation has decided to begin sharing her writing with the world.

The first peek will come next month, when a survey exhibition of Bourgeois’s work opens on May 10 at Glenstone, Mitchell and Emily Rales’s private museum in Potomac, Maryland. The catalogue accompanying the show includes nearly 50 pages of previously unpublished diary entries that the artist wrote between the ages of 14 and 91.

Bourgeois’s writing feels more like a series of carefully composed poems than slapdash accounts of the day. Like her art, her words almost bubble over with longing, loneliness, and angst. The selections in the Glenstone catalogue trace her journey from a teenager living with her tapestry-restorer parents in Choisy-le-Roi to a twenty-something art student in Paris, then to a young mother, and then finally to an aging artist in New York City. Her struggles with depression are never far from the surface.

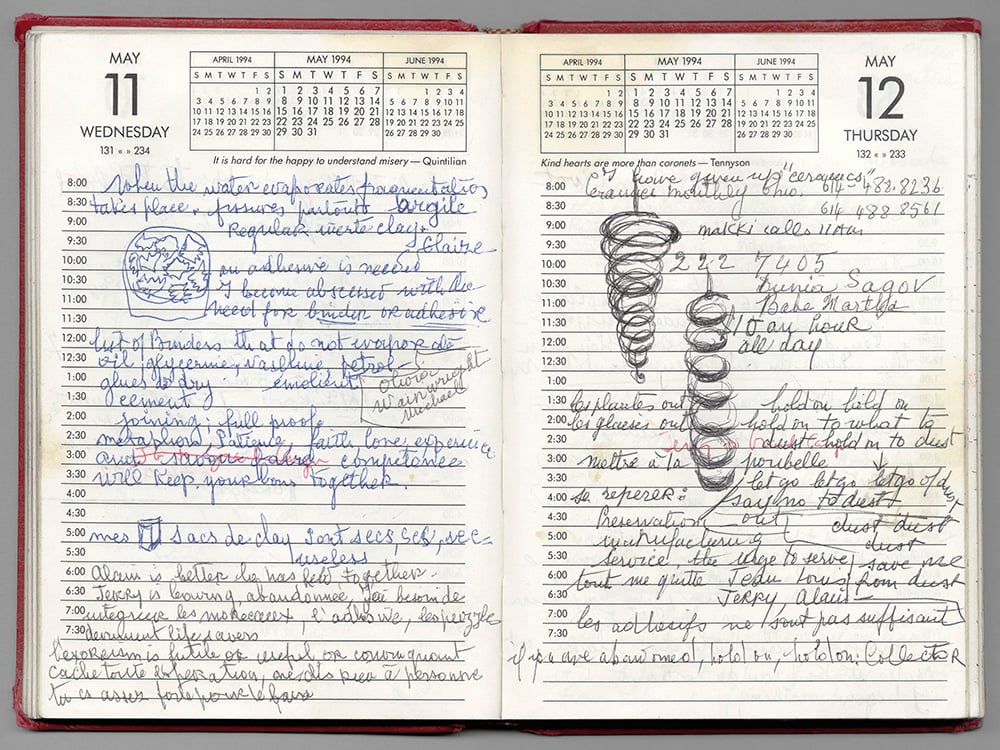

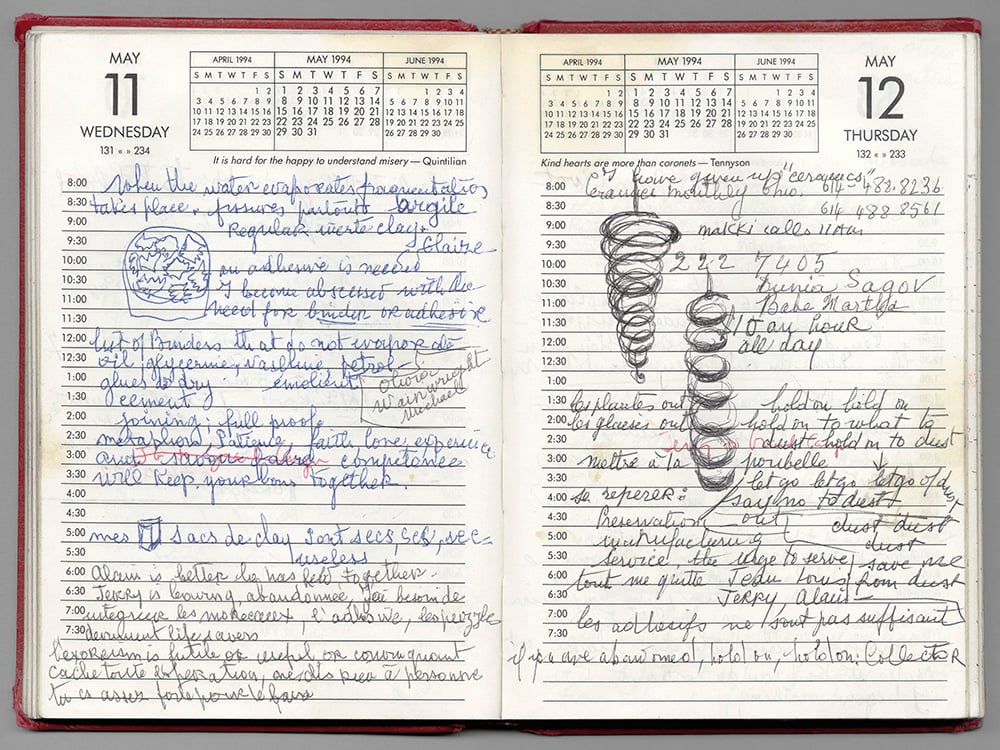

Louise Bourgeois, Diary spread, May 11–12, 1994. Collection Louise Bourgeois Archive, The Easton Foundation. © The Easton Foundation/VAGA, NY.

“You can sense her anxiety at an early age,” said Jerry Gorovoy, the artist’s longtime assistant and the current president of the Easton Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to Bourgeois’s life and work. “I think she needed to write in the same way she needed to make art. She had this pathological need to record.” Near the end of every year, he recalled, Bourgeois would get a fresh diary and stick the one from the previous year on her bookshelf. She wrote almost every day.

Although several books have included excerpts of Bourgeois’s writings over the past two decades, Gorovoy says the published material represents only a small sliver of her output. Her diaries, in particular, have largely been accessible only to scholars. Eventually, Gorovoy says, he would like to publish more facsimiles of the diaries themselves, which include drawings and diagrams.

Some of the entries—like one written on Christmas Day in 1928, which also happened to be her 17th birthday—could easily be confused for poems by the Modernist writer William Carlos Williams:

the countryside is covered with snow

it is beautiful, but doesn’t produce an

impression of sadness like pine trees

covered with snow ordinarily do

Other passages are so intimate that reading them almost feels like sneaking inside the artist’s head in the middle of the night, when she is turning the events of the day over in her mind, unable to sleep. In 1938, she wrote:

Pain does not frighten me as

long as it is an enrichment but I am so afraid

to use my strength for nothing I feel time elapse elusive

and so fast that I am afraid.

Many poems do not unfold as you might expect. A 1971 entry written on the occasion of the wedding of the former Philadelphia Museum of Art director Anne d’Harnoncourt, for example, is not a congratulatory testament to the power of love but a deeply bitter meditation on envy. Like her art, Bourgeois’s poems often refer back to unresolved memories—Gorovoy notes that this one might relate to her notorious jealousy of her own sister’s marriage.

Although none of it is particularly lighthearted fare, a few excerpts are less wrenching. In one, she describes her distaste for Richard Nixon; in another, the delights and frustrations of breastfeeding. (Gorovoy says the most quotidian entries—about who she met for lunch or the appointments she had on a given day—have been left out, though this careful record-keeping has proven invaluable to scholars.)

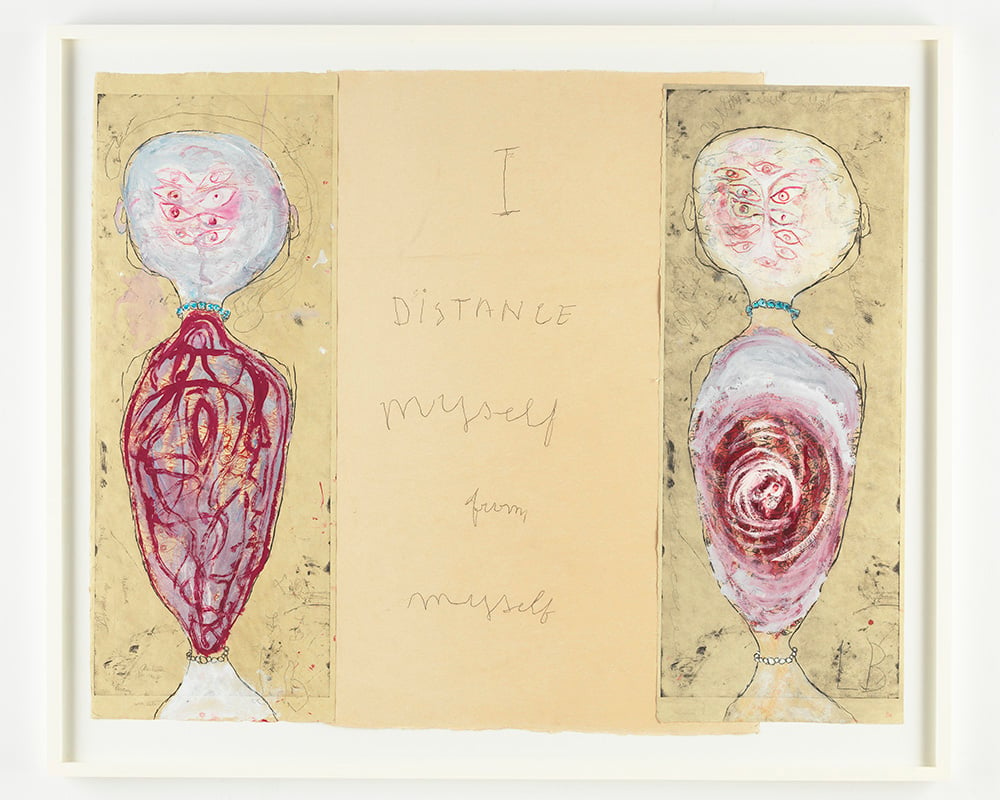

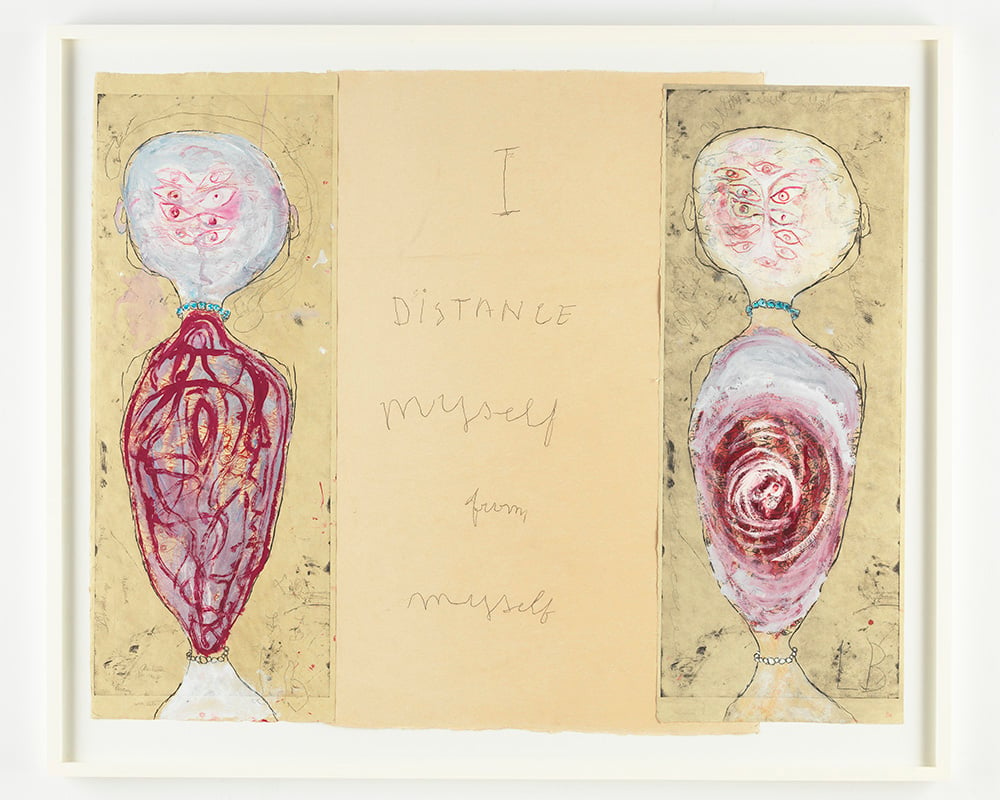

Detail from Louise Bourgeois’s I GIVE EVERYTHING AWAY (2010). Collection Glenstone, Potomac, Maryland. © The Easton Foundation/VAGA, NY, photo: Christopher Burke.

The artist also created boxes’ worth of notes, reflections, and lists when she was undergoing psychoanalysis in the 1950s. She tucked them away in a closet and forgot about them for decades; the first batch was only recovered in 2004.

The public will get a deeper look at these writings in 2020, according to Gorovoy, when Princeton University Press will publish a dedicated book on the subject. Some of the materials will also be included in a catalogue for an exhibition on Bourgeois and Freud at the Jewish Museum in New York that is due to open later the same year.

Gorovoy acknowledges that Bourgeois never thought of herself as a writer. In an early entry included in the Glenstone catalogue, she profeses: “I do not start it with the intention of ever letting anyone read it.”

But he doesn’t feel conflicted about bringing her writing out of the shadows now. Her art is already so biographical and personal, he notes, that he considers the oeuvres as “two sets of diaries: one is in writing and one is a body of work.”

Furthermore, when her psychoanalytic papers were rediscovered, “she didn’t say, ‘I don’t want anyone to see this,'” he recalled. “And if someone was doing research she’d either refer to the diary or let them see it. Now, we’re opening it up to more people.”

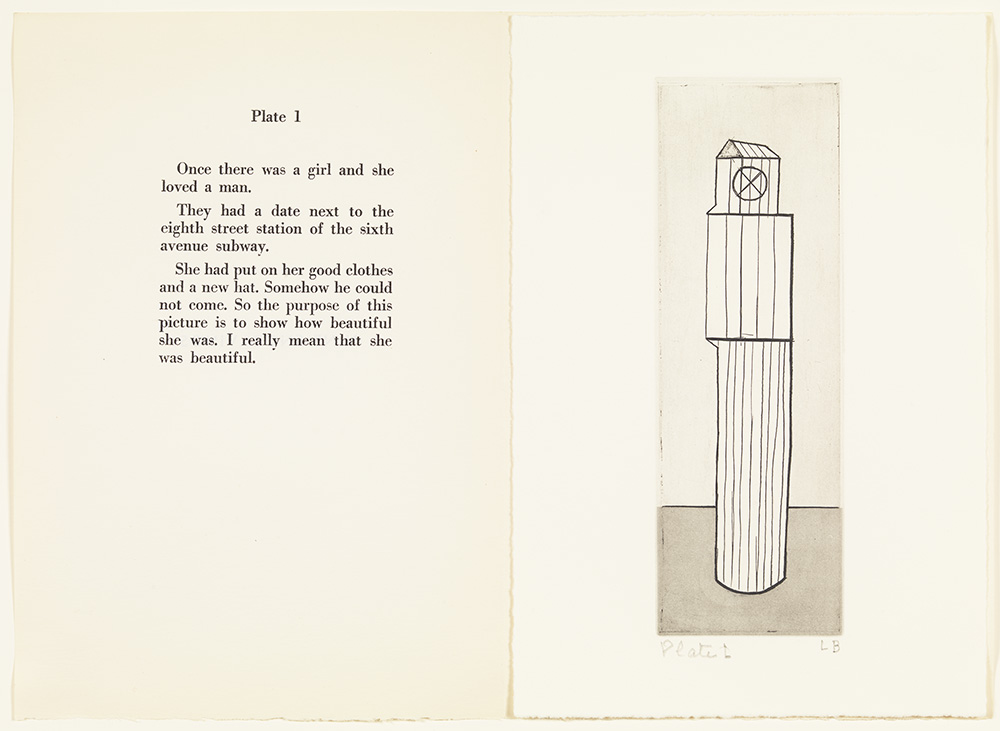

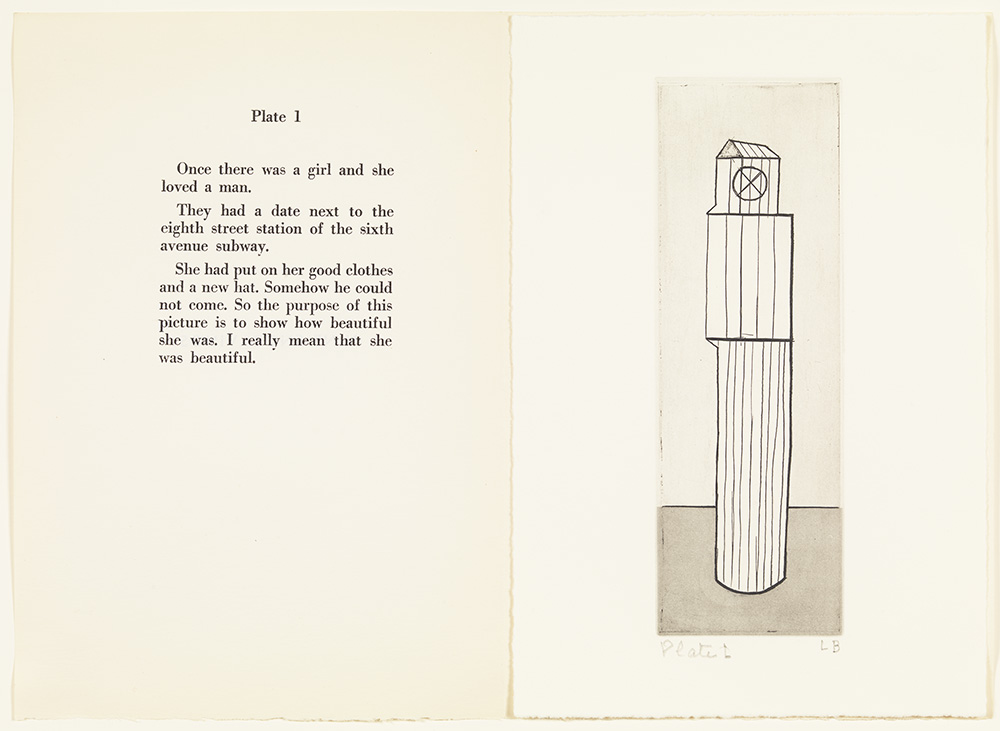

Louise Bourgeois’s HE DISAPPEARED INTO COMPLETE SILENCE Plate 1, (194–2005) Collection Glenstone, Potomac, Maryland. © The Easton Foundation/VAGA, NY, photo: Christopher Burke.

Below, read the earliest entry in the Glenstone catalogue. Bourgeois wrote this poem on July 8, 1926, when she was just 14 years old, about Simone, one of her oldest childhood friends.

Here is the dream.

As in all my dreams I am an

18 year-old young woman I am the most happy happy

so I was leading in Paris a delicious life of

parties and pleasures. Being tied, for

2 months I vanished into the country where life for

me took a real turn. I frequently

walked alone in the woods, so one day

during one of my walks I found in

a clearing an exquisite title shepherd who was about

the same age as I, it was Simone as a man, we talked

for a long time and every day we would see each other

Since I was soon to go back to Paris I offered my

beloved shepherd to come along and in the

big city life with him was for me

charming and peaceful.

One day one of my friends off invites us to

a masquerade, right away I suggest to my friend

a shepherd costume, with me coming as

a shepherdess . The whole evening we danced

and we were so gorgeous that very soon

everyone noticed us. al A large circle formed

around us and we were twirling

round and round. All of a sudden the vaulted ceiling opened up and

as we ascended we remained in each other’s arms until

slowly descending back to earth we

ended up where we first met…

the ending is easy to imagine”

I woke up, really this time what joy

to have had this dream it seemed that for a

long time I had been one with Simone.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.