Art & Tech

The Curious Case of the 222 Other Artists Who Just Landed on the Moon Who Are Not Jeff Koons

The saga of the Lunaprise Museum.

The saga of the Lunaprise Museum.

Ben Davis

Last week, the media lit up with news that a payload of 125 tiny Moon Phases sculptures by Jeff Koons had touched down aboard the Odysseus lunar lander. I was going to write something on it—but then a weirder story zoomed onto my space radar.

It turns out that Koons is not the only artist who made a moon landing last week. In fact, he is but one of hundreds.

This rabbit hole opened for me via comments on Koons’s Instagram posts about his lunar feat (Kate Brown pointed these out during a discussion of Moon Phases for our podcast). Whenever Koons has posted about the moon mission, an artist who goes by the name @transparentartist has weighed in with comments demanding that Koons not hog the spotlight: “This is a group effort my man! Again proud to be displayed next to you, but let’s call it for what it is. 222 of the best artists on earth got chosen collectively.”

I didn’t think much of it—until I got an email blast from Stacy Engman, the socialite and curator turned NFT entrepreneur known for her signature tiara and tabloid run-ins. She also claims to have art on the Odysseus mission. Then there was a press release from a PR company, offering to plug me into two other artists, NFT creator Kelly Max and musician Brayden Pierce, who also put work on the moon.

Stacy Engman at the Kennedy Space Education Center for the launch of the Lunaprise Museum. Image courtesy Stacy Engman.

Further web searching brought me to a claim that Moonbirds, an NFT collection of owl-themed pixel art, had hitched a ride to the moon. A designer claimed that she was now the first fashion designer on the moon. Another artist said he had sent some animations to the moon to raise awareness about conservation. A podcast clip introduced me to a Mexican artist who said he had sent a papaya to the moon to represent Mexico.

All these scattered references led back to something called the “Lunaprise Museum,” the work of a Beverly Hills-based outfit called Space Blue that describes itself as “a pioneering company focused on creating a unique lunar museum.” So what is it?

The links on the “Press Kit” section of Lunaprise’s website are inoperable, and several messages I sent to email addresses listed there bounced or went unanswered. (Ditto for those of an affiliated organization, Galactic Legacy Labs.)

Promotional graphic for the Lunaprise Museum.

Space Blue communicates with the public via a blog on Medium, but it last posted there in November 2023, when it was promoting moon-themed events during Art Basel Miami Beach. The Space Blue Instagram has been posting regularly about the Lunaprise Museum as part of the Odysseus mission, but it is very difficult to make sense of. It has fewer than 700 followers.

And yet, the Lunaprise Museum is real. In a presentation from the stage of the Quantum Miami crypto conference last year that has been preserved on YouTube, you can see its organizers screen a slickly produced trailer about the space-art initiative.

“We’re taking the works of 222 NFT-focused art projects, who are already followed by billions of appreciative followers, to the moon,” the pitch goes. “Alongside artwork from these top creators will be digital music, film, fine art, NFT art, photography, animation, and art collections, all to be preserved for at least one billion years in a patent-protected, indestructible time capsule, creating the world’s first off-earth-based museum. We call the museum that lands there the Lunaprise.”

In yet another video interview from Mining Disrupt, another Miami cryptocurrency conference, Space Blue curator Dallas Santana boasts of having chosen 222 projects for the Lunaprise Museum. The only one he talks specifically about is his own film, a sexy spin on Mad Max called The Ninth Raider. Santana says that the crypto-funded flick will now have bragging rights as “the first full motion picture to land on the moon.”

Throughout the interview, Santana holds his fluffy Arctic dog, Marshmello. The dog happens also to be the subject of NFTs which are being advertised as part of the Lunaprise Museum trove.

As of this writing, that Mining Disrupt clip has only a little more than 100 views. For an initiative that seems like a publicity stunt, the Lunaprise Museum has generated remarkably little publicity—so far.

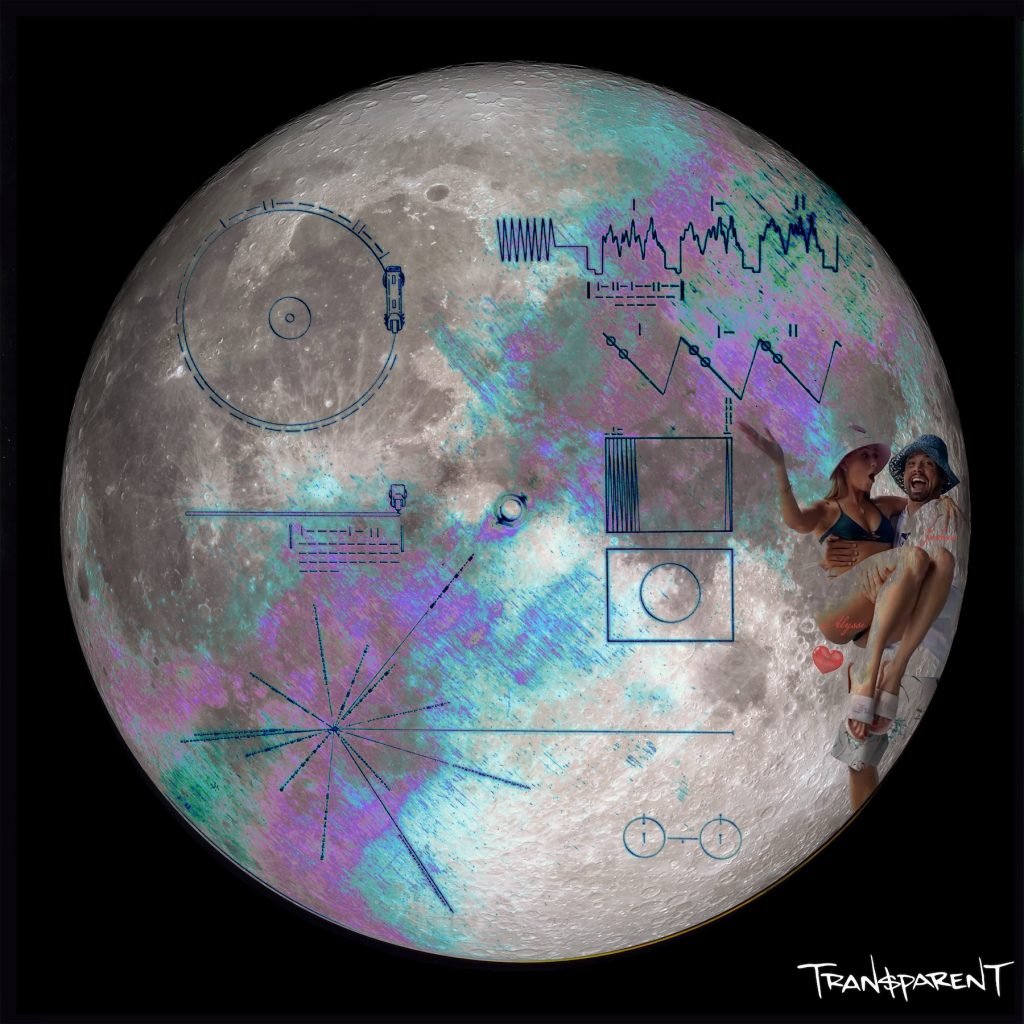

Basically, the Lunaprise Museum is not a physical museum. Nor is it even a collection of tiny sculptures, à la Koons. It is a set of nickel disks that resemble a DVD, which have hitched a ride on the Odysseus mission, clamped to the exterior of the 14-foot-tall lander. According to Intuitive Machines, the company that made the lander, it is one of several “commercial payloads” on the for-profit flight. Others include 6 NASA instruments (for which the government has paid $118 million to the private company), Koons’s sculptures, and gear from a few other companies hoping to use the mission to drum up interest (e.g. Columbia Sportswear, Lonestar Data Holdings).

Participating artists sent images or data to Space Blue, which then had them inscribed on the disks at microscopic scale. Supposedly, the Lunaprise Museum has 77,000 of these so-called “Lunagrams” etched into the disks, from 222 artists, creators, or NFT initiatives, giving participants the right to say that they have sent art to the moon.

Graphic from Intuitive Machines showing the Lunaprise concept.

In a further confusing twist, the Space Blue-curated contemporary art component seems to be just a tiny star within the immense galaxy of data on the disks.

The Arch Mission Foundation, an organization promising to get a “backup” archive of earth’s culture on the moon, is also a participant. Thus, a press release claims that the Lunaprise disks also contain “a 30 million-page ‘Galactic Legacy Library,'” which incorporates all of English-language Wikipedia, numerous e-books from Project Gutenberg, an “archive of over 7,000 human languages,” a huge amount of music, the magic secrets of celebrity illusionist David Copperfield—“including how he will make the moon disappear in the near future”—and much, much more.

A graphic from the Arch Mission Foundation website showing a dedication included in the “Lunar Library.”

No comprehensive public list of the 222 artists selected for the Lunaprise Museum exists. No one I talked to had seen one. Some seemed to think that Jeff Koons’s Moon Phases project was also part of the Lunaprise Museum. It is not.

The Lunaprise Museum has promised a metaverse component as well, where all the selected artworks can be experienced in virtual space. I also heard talk of the possibility of a physical installation of some kind at the Smithsonian. As of now, these remain just promises.

The exact business details of the proposition also remain a bit fuzzy.

On Lunaprise’s website, initial registration for an “Artist ID” costs $35, with the option to upgrade to Level 2 or Level 1 “Vanity Numbers” for $49 or $99 (the distinction is not clear). Commercial enterprises, defined as “art projects or projects with over $1.0 million annual sales,” were being charged $350 for the registration. (The Internet Archive shows that a range of packages have been offered in the past.)

In an interview, digital art entrepreneur Kelly Max told me he came into contact with Space Blue with the hope of getting his Modernist collection of NFTs aboard the Odysseus mission. One of his submissions, MOONRIDER—a poppy, hard-edged image of a woman in chunky yellow sunglasses, a spacesuit, and a ball-cap that says “Moon Rider,” created by artist Samy Halim and inscribed with the initials of 180 of the project’s supporters—caught the eye of curator Dallas Santana.

“He asked us to design something for the mission—the official mission patch, the mission identity,” Max recalled. “In return we were able to get more of our Modernist collection on the mission. He wouldn’t pay us, but he said, ‘Look, if you can do this for me, and if you can help us, we can help you.’”

The resulting Lunaprise graphics now feature on bomber jackets that are on sale for $349 as merch on the Space Blue site. Prints of the official Lunaprise mission patch go for $999, while artists can buy wood-framed prints of their own Lunaprise art from the mission for $849 to $1,899, ordered through Max’s Portland, Oregon-based Modernist company.

Screenshot of an entry for merch on the Space Blue website.

While Max said he did not concern himself with the financials of the operation, he told me his understanding is that Space Blue attempted to make room for emerging artists while charging brands or more successful projects at levels ranging from thousands to tens of thousands of dollars, based on their resources. “The curator balanced it out between giving people a story of opportunity, and on the other hand saying, ‘Look, if you are only interested in commercial, you have to pay to become a part of it,’” he said.

Speaking to me alongside Max was Brayden Pierce, a musician whose EDM track “Capture the Moon” is also part of the Lunaprise Museum archive.

Together, Max and Pierce have forged an endeavor called Mooon Party, which bills itself as an “event collaboration celebrating music, art, moon culture, and human history.” Thanks to a partnership with Space Blue, the duo told me, Mooon Party will be able to promise any acts they book that their performances will be archived on the moon in future Lunaprise missions.

“That’s how we can preserve culture, like in the pyramids,” Max said.

“It’s even grander,” Pierce added. “This little disk lasts a billion years. The pyramids have only been around for a few thousand years.”

Mooon Party also programmed the official Space Blue “launch party” to mark the blast-off of the rocket on February 13 (due to complications, the actual liftoff did not take place that day). For the event, they rented out a section of the Center for Space Education, located at the Kennedy Space Center. “Artist” tickets were $385, with super-VIP tickets going up to $5,000.

The keynote speaker of the event was Lorenzo de’ Medici, who advertises himself as a direct descendent of the Medici clan. He has been brought on board as a “joint curator” of the Lunaprise Museum. Lorenzo is perhaps best known for his stint on the 2012–13 TLC reality show Secret Princes, though a somewhat garbled post from Space Blue focused on his Italian Renaissance cred: “He brings centuries of art history to his heritage, his family, the very backers and patrons behind Leonardo Davinci, and Masters like Michaelangelo and the resulting Van Gough masterpiece, considered the most priceless work of art: The Mona Lisa. His family is also credited with establishing the early banking systems.”

In a clip on Instagram, Lorenzo de’ Medici can be seen taking the stage to speak at the Lunaprise kick-off party as the Star Wars fanfare plays.

Days later, news came in that the Odysseus lander had tipped over, sending the stock of Intuitive Machines wobbling and prompting a strangely defensive post from Jeff Koons. I asked Max and Pierce whether the mishap affected their opinion of the mission.

They were unfazed. If anything, both saw it as representing that they had come out on top—quite literally.

“If you think about it, when it tipped over, Jeff Koons’s sculpture is down here and we’re up here on the opposite side,” Max said, showing an image of the lander and pointing to where the respective payloads were attached. “We are basically now shining out into the universe.”

A number of Lunaprise artists made the trip to Cape Canaveral for the Mooon Party launch event, posting from the festivities. One who did not make the pilgrimage, because of a previous commitment to be in Las Vegas for the Superbowl, was the man behind the @transparentartist account that brought the Lunaprise Museum to my attention in the first place.

It turns out that TRAN$PARENT, a.k.a. Josh Leidolf, is a voluble Florida-based artist known for paintings that riff on the form and meaning of currency. His collectors include rapper Post Malone and restaurateur Guy Fieri, he told me.

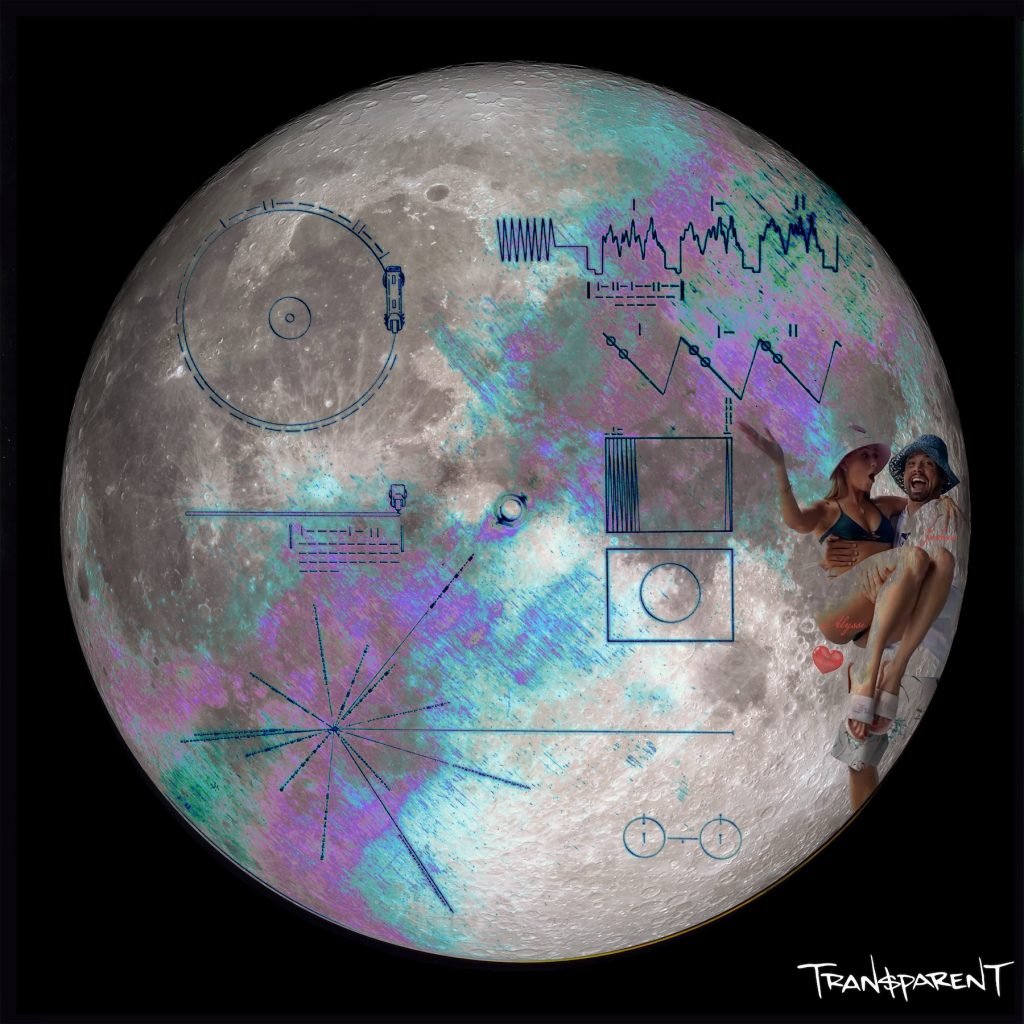

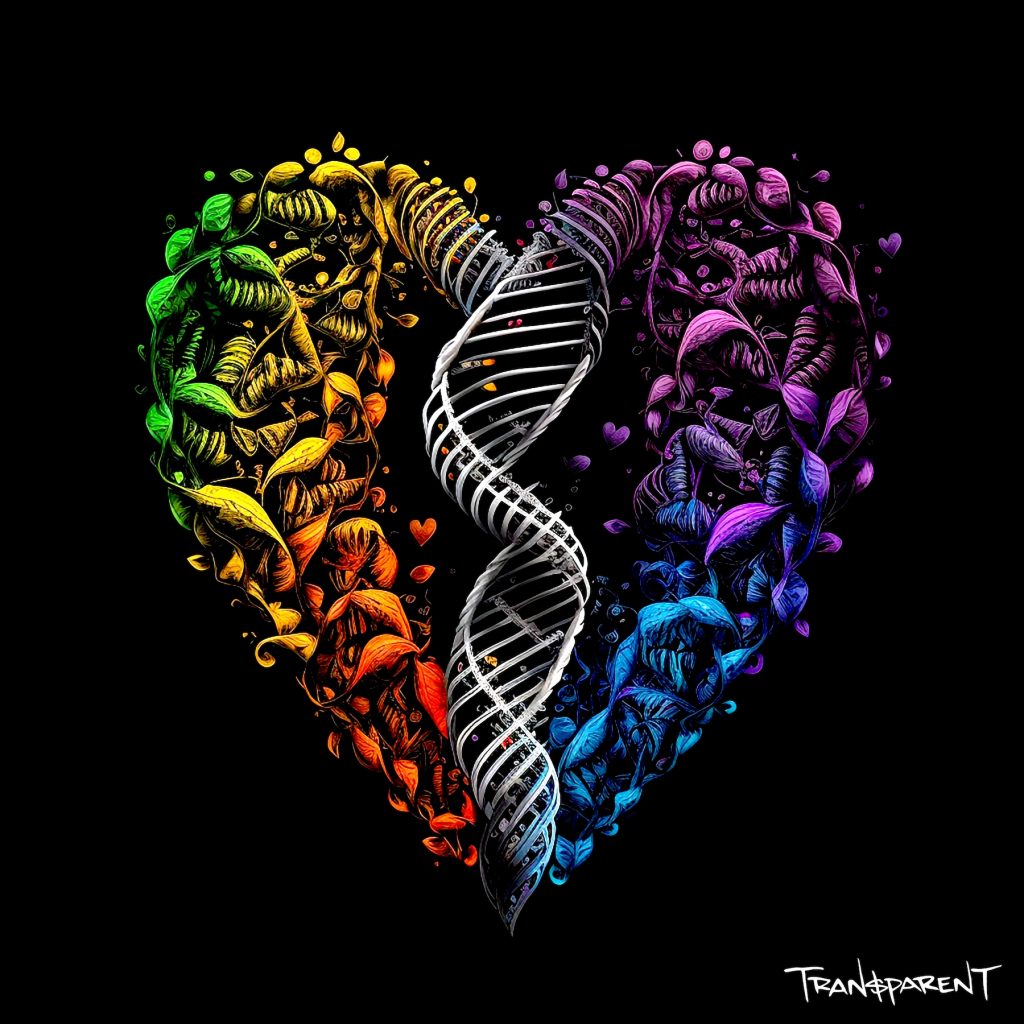

TRAN$PARENT’s Love Gene 9A, a work aboard the Lunaprise Museum. Photo courtesy TRAN$PARENT.

Leidolf confirmed by phone that he had not paid to be aboard the Lunaprise Museum, and had been brought into the initiative by his friend Scott Page, the one-time saxophonist for Pink Floyd, Supertramp, and Toto, who has lately pivoted to Web3 ventures. Some 10 pieces Leidolf has had inscribed on the nickel moon disk mingle the image of a DNA helix with the shape of a heart, while another, Moon Lovers Forever, is a tribute to his wife.

“Future humans or aliens will be able to figure out what the double-helix of genetic code meant, but they will have no clue what the heart meant,” Leidolf explained. “That’s why I put my wife and I in the moon.”

Because he sees the mission as representing humanity, he was disappointed with Jeff Koons, not just because Koons had so far declined to use his platform to share the spotlight with other lunar artists, but because the subject of Koons’s sculptures—the moon itself—wouldn’t serve as much of a message to the future.

“Any future humans or aliens who find this thing are gonna know long, long, long before they get to the moon what the phases of the moon are,” Leidolf said. “What a gimmicky thing to do.”