Art World

The Iconic Drag Artist Lypsinka Returns for a Grandiose, Cinematic Spiral

The multi-talented John Epperson teamed up with Chloë Sevigny for 'Lypsinka: Toxic Femininity,' a hypnotic return to the mass consciousness.

“Hell is not other people,” said John Epperson by phone earlier this week. “Hell is myself.” The writer and star is behind the short film Lypsinka: Toxic Femininity, which dramatizes the existential crisis of its titular drag persona. It veers from careening comedy to camp performance art pathos.

It’s streaming for free through February 16 at The New Group theater’s website. Its director, Chloë Sevingy, deftly captures the inner turmoil with expressionist flare. It’s a complex assemblage of dream sequences, cascading points of view, interior monologues, and musical interludes, and was filmed in three days. Many sequences were captured on vintage video cameras (Sevigny found the cinematographer, the video artist Jennifer Juniper Stratford, on Instagram). It’s evident that it was a passion project for Sevigny and Epperson and not a side venture.

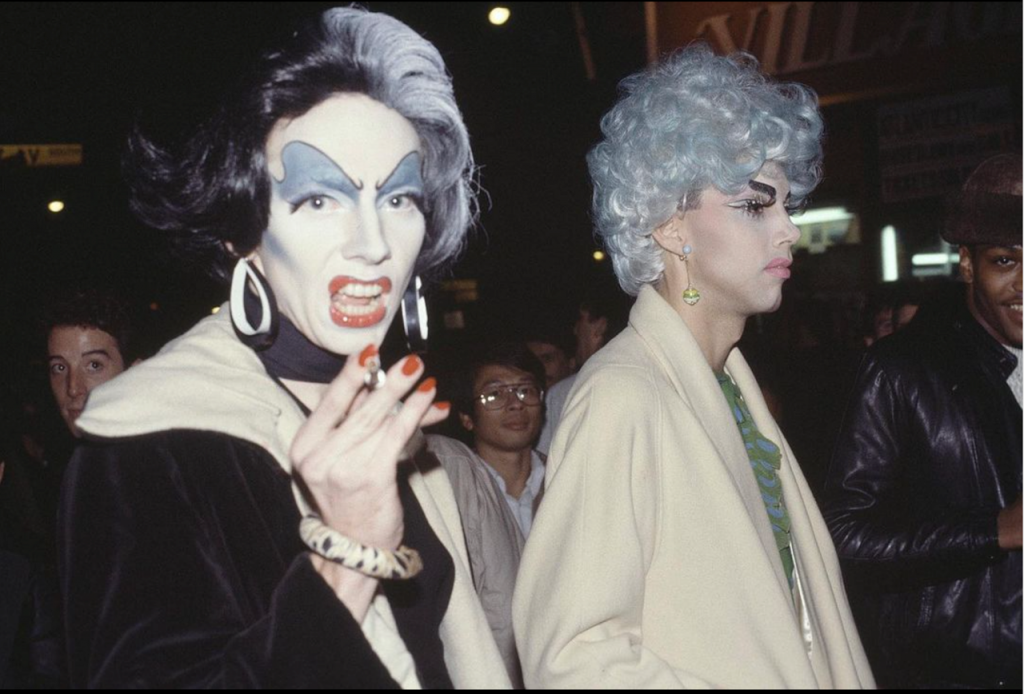

Lypsinka is so complete that it’s hard to separate her from her creator. She emerged from New York’s 1980s downtown performance scene at venues like Pyramid Club. Her combination of 1950s housewife kitsch bliss and vamp glamour was a throwback antidote to the rigors of the era. Lypsinka was no impersonator. Epperson specialized in creating sound collages with assorted pop culture voices. With uncanny delivery, he constructed new narratives and evolved his pastiche character. Lypsinka would go on to have multiple Off-Broadway shows and even became a Thierry Mugler muse.

Lypsinka illustration by Justin Teodoro. Courtesy of the artist.

The bulk of the film’s dialogue is sourced from a bananas, no-holds-barred 1965 recording of Judy Garland, wherein the apparently inebriated star attempts to produce an autobiography, but is unsure whether the tape recorder is working. The other portion consists of Joan Crawford reading aloud from her rather unhinged 1971 memoir My Way of Life. These diametrically opposed, intertwined monologues become the narrative of Lypsinka. “There’s a reason that Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is still popular,” Epperson said. “We’re all at least double-sided.”

We caught up with Epperson, who is also a classically trained pianist and film historian, to find out what makes Lypsinka tick.

I was lucky to have gone to the premiere and seen the film on the big screen. I had no clue it was recordings of Judy Garland and Joan Crawford. I assumed you’d written the Garland portion. It’s like the holy grail of batshit craziness to hear a star sound like that.

A lot of my work is about the trap of stardom, I think that’s what this is about–the stuff that you go through behind the scenes. The public only sees what it’s shown. I don’t think it really matters if you know who it is or not. But if you do happen to know, it may add an extra layer for you, but it also could take you out of the movie if you’re focusing on her instead of the Lypsinka character. The way I see it, it’s no longer Judy Garland, it’s Lypsinka.

Do you remember Kim’s Video on St. Mark’s Place? I loved that store because they had so many obscure things, not just videotapes. There was this CD, Judy Garland Speaks, and I thought, “what the hell is this?” And so, I bought it. Swifty Lazar, the book agent, had tried to get her to write a memoir. But of course, he knew she was not disciplined enough to write it and so he gave her a tape recorder. She started talking, not even sure that the thing was functioning properly. But it turned out it was. She was revealing too much about herself and about other people, and none of it was usable for a memoir in 1965, but somehow it didn’t get tossed. If any of that had come out, then it would’ve been disastrous—not that her life wasn’t a disaster anyway.

The Crawford thing, she recorded it in her home just as Garland did. But she had a purpose. She was disciplined, and actually did write. She recorded it for the Library of Congress, but also so that sight-impaired people could hear. Her need to be noticed fascinates me. She was constantly promoting herself.

Another person who fascinates me, who was at MGM with Crawford and Garland, was Greta Garbo. She didn’t want to be noticed. Paradoxically, by walking away from her fame, she became even more famous. Crawford and Garbo didn’t live that far from one another, and yet they weren’t friends, certainly. But I’ve fantasized that when Garbo would go on her afternoon walk, she may have walked in front of the Doubleday store on 5th Avenue and saw Joan Crawford’s book in the window and perhaps thought to herself, “Will that woman ever shut up?”

An early Lypsinka flyer. Courtesy of the artist.

Do you direct your creativity into different outlets?

Yeah, but I don’t think anybody’s interested. This Lypsinka character is powerful and people don’t want to think that I can do anything else. I’ve tried to prove that I can. It’s not been easy. I’ve written a full-scale musical. It’s my own take on Hansel and Gretel. Lypsinka is a character in it. I don’t think it’ll ever get produced, but I’m pleased with myself for sitting down and writing it. And I had done shows like that at The Pyramid [nightclub] in the 1980s—I’d written books, music, and lyric shows, but then Lypsinka became popular so I put that part of myself aside.

How did Lypsinka start out?

I’ll go back to the beginning. When I was a kid, I had two older sisters (I say had because one of them is deceased). The older one was very good at entertaining her younger siblings. My father had a record called For Men Only with a picture of Jayne Mansfield on the cover. She’s not on the record, just on the cover. The songs were covers of popular songs at the time. My sisters put on a little show for me and my mother, lip-syncing to this record. My mother called it pantomime.

I was fascinated by it. And then when I got to college in Jackson, Mississippi, I discovered the local gay bar and the drag queens were lip-syncing, which was what my sisters had done. By then, I had learned who Charles Ludlam and Ionesco were. I saw this whole lip-syncing thing as absurd theater, a ridiculous theater, but I still didn’t know what to do with it. I moved to New York in 1978.

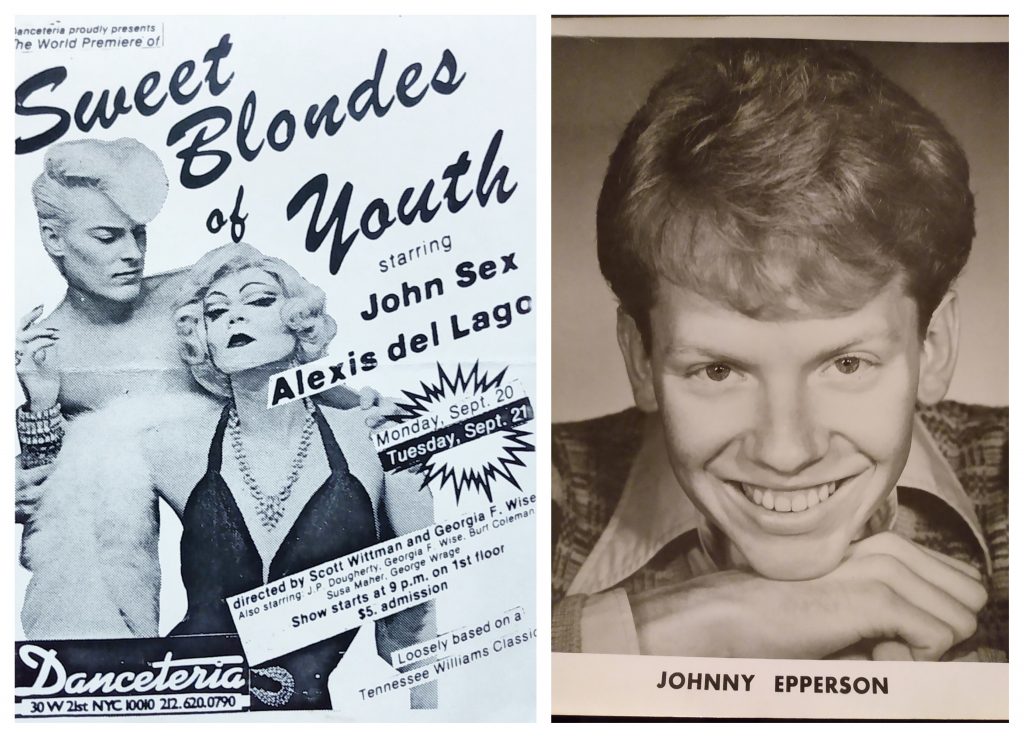

A flyer for a John Sex production and can early Epperson publicity image. Courtesy of John Epperson.

How did you get involved with Club 57? MoMA did a wonderful look back at this East Village venue and the creative and nightlife scene around it.

Do you know who John Sex was? He was kind of a parody of Elvis and Liberace, poking fun at fame, but also wanting it. Very pretty, very handsome guy. He died of AIDS, like so many others. It’s kind of hard to describe what his creation of himself was, but it was a self-creation that had a sense of humor about it.

Ann Magnuson was the manager of Club 57. It said in the newsletter, “John Sex is gonna be doing Acts of Live Art and if you wanna be in the show, here’s his phone number.” I left a message on his machine. The day before the show, he called me and he said, “So, you’re gonna be in the show tomorrow?” And I said, “Well, John, I called you weeks ago and never heard back. I haven’t planned anything.” And he said, “Oh, but I need you. You have to do it.” So, I quickly pulled a couple of looks together and I remembered that For Men Only album, which I still have. I lip-synced one of the songs that my sisters did, and a song from Valley of the Dolls. That was the first public lip-syncing I ever did.

And years later, photographs of that appeared in books and the museum exhibition. I had no idea that a photographer was present. I couldn’t believe it. But that was very primitive.

However, I took a trip to Paris in the summer of 1981. I went to Michou a very famous drag club in Pigalle. I think it’s still open, even though Michou died a couple of years ago. It’s kind of a tourist trap. But these were professionals, lip-syncing mostly to celebrities like Josephine Baker, Liza Minnelli, or Edith Piaf. And they tried their best to look like those people. I was impressed at their abilities, and that they were making a living in Paris and it wasn’t a gay bar in Jackson, Mississippi. So that’s when I thought maybe there is something to this lip-syncing thing, and I can kind of poke fun at it and do something serious at the same time.

But I needed to make up a character, and the character needed to have a name that lets the audience know that I’m in on the joke. I want it to sound chic too. I was thinking of fashion models like Dovima, Veruschka, and Apollonia, and I thought: Lypsinka.

There is a great video of you performing with a boombox on Christopher Street.

By then I had done one night at Club 57 and I thought what if I go to Christopher Street and take a boombox and lip sync? And the crowds gathered around, they loved it. I wanted to be noticed. I liked the adulation. What can I say? At the end of Gypsy, when Gypsy says to her mother, “Why did you do it?” The mother says, “I guess I just wanted to be noticed.” Judy Garland wanted to be noticed. Joan Crawford wanted to be noticed. Garbo did not want to be noticed but got noticed in spite of it.

Epperson: “Craving attention, and finding it, on Christopher St. during Halloween festivities, with deceased friend Steve Mann, circa 1983. Dickens was right: the best of times, the worst of times.” Courtesy of the artist.

Lypsinka seems to culminate in these overlapping surreal planes of 1950s existences. Did you always have retro tastes? In the 1980s, were you ever into Madonna?

I’m not up on current stuff, and in the 1980s, I felt like I wasn’t up on current stuff. Looking back now, popular culture then may have been more interesting than I realized at the time. And of course, Reagan got elected and AIDS happened and there was so much ugliness and yet, things were happening for me. I have this cockamamie theory that when AIDS happened and gay men were told, “you can’t have sex anymore” (and sex had been very important to them), then they thought: “Well, if we can’t have sex, what can we do? We need an active fantasy life. I know. Let’s go to a drag show.” Before that, drag performers had been looked down upon. But now they were like the USO [United Service Organizations] girls. They were helping fight the fight.

I don’t get your trajectory from Christopher Street.

I got a job at American Ballet Theater as a rehearsal pianist, which required my getting up in the morning and going to work. You had to be very disciplined to do that job and I couldn’t hang out in the East Village anymore because they would go traveling and I’d disappear for months. But the ceiling on that job is pretty low. Although I loved it at first—it was super glamorous and I was working with the greatest dancers in the world—after a while, it wasn’t satisfying artistically for me. I wanted to do more than that.

Lypsinka prepping in the Pyramid basement in 1987. Photo: Linda Simpson.

I bumped into John Sex and he said, “Are you performing?” I said no. And he said, “Well, you should be.” And I said where? He said at the Pyramid Club. By then, Club 57 had closed. He said: “Come to my show. I’m performing Saturday night. I’ll introduce you and they will give you a booking.” He lived up to his word. They gave me a booking Sunday night. They trusted him. And I did my first performance at the Pyramid Club and the crowd went crazy. It was the crowd that I had been looking for, other than on the street, and I didn’t have to promote.

The crowd was already going to come on Sunday night no matter what, and they loved it. Every blink of my eyelashes—they screamed for it. This is what I’ve been looking for. That led to my first off-Broadway show in 1988 and a lot of famous people were coming to see that show—Rosemary Clooney, Leslie Gore, Rod Steiger, Francesco Scavullo, Monique van Vooreen, Paul Reubens. And I came to see the Pyramid Club then as the 1980s version of what the Continental Baths did for Bette Midler. And I thought: this can be a springboard to something else.

More Trending Stories:

A Case for Enjoying ‘The Curse,’ Showtime’s Absurdist Take on Art and Media

Artist Ryan Trecartin Built His Career on the Internet. Now, He’s Decided It’s Pretty Boring

I Make Art With A.I. Here’s Why All Artists Need to Stop Worrying and Embrace the Technology

Sotheby’s Exec Paints an Ugly Picture of Yves Bouvier’s Deceptions in Ongoing Rybolovlev Trial

Loie Hollowell’s New Move From Abstraction to Realism Is Not a One-Way Journey