Archaeology & History

Machu Picchu Is Even Older Than Previously Thought, New Radiocarbon Dating Shows

The colonial records kept by the Spanish appear to have been wrong.

The colonial records kept by the Spanish appear to have been wrong.

Sarah Cascone

Peru’s famous Inca city of Machu Picchu, perched high in the Andes Mountains, is possibly several decades older than experts previously thought.

New evidence published in the journal Antiquity found that the UNESCO World Heritage site was inhabited from about A.D. 1420 to A.D. 1530, around the time it was conquered by the Spanish. That suggests it was built at least 20 years earlier than previously accepted historical records, reports Smithsonian Magazine.

“Until now, estimates of Machu Picchu’s antiquity and the length of its occupation were based on contradictory historical accounts written by Spaniards in the period following the Spanish conquest,” archaeologist Richard Burger, an anthropology professor at Yale University, said in a statement. “This is the first study based on scientific evidence to provide an estimate for the founding of Machu Picchu and the length of its occupation, giving us a clearer picture of the site’s origins and history.”

Burger and his team used accelerator mass spectrometry, an advanced form of radiocarbon dating, to test 26 sets of human remains found at the pre-Columbian site in 1912. (The remains have been repatriated to Peru, as part of an agreement between the government and the university signed in 2011.)

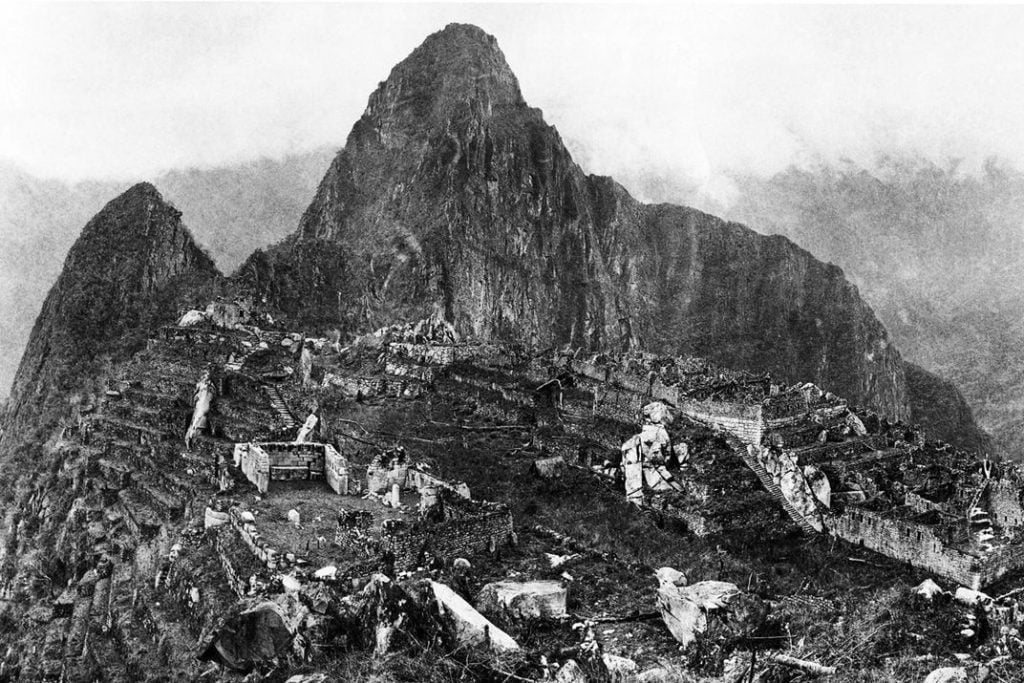

A 1912 photograph of Machu Picchu by Yale professor Hiram Bingham III, who rediscovered the city a year earlier. Photo by Hiram Bingham III, National Geographic, public domain.

The bones and teeth researchers tested showed no signs of heavy physical labor, indicating that they belonged to attendants to the emperor after the site’s completion, rather than to workers from its construction. That would mean Inca emperor Pachacuti, who built Machu Picchu as his country estate, came to power before the year 1438, the date cited in colonial records. Based on the later date, experts had estimated that the city had been built between 1440 and 1450.

The new finding suggest that historians need to reevaluate assumptions made about the early years of the Inca empire that are based on colonial sources.

“Dating Inca sites is subject to speculation because written accounts and archaeological evidence do not always correspond,” Gabriela Ramos of Cambridge University told the Guardian. “For decades, historians and anthropologists have relied mostly on written accounts and it is rather recent that archaeological findings, use of radiocarbon dating, and other techniques are contributing to, add to or change our understanding of pre-Columbian societies.